Can your website be your API? Drew McLellan Institutional Web Management Workshop, July 2007 Hello! - allinthehead.com, microformatic.com - group lead for web standards project - also work at Yahoo! I’m not speaking for Yahoo! today.

A presentation at Institutional Web Management Workshop in July 2007 in York, UK by Drew McLellan

Can your website be your API? Drew McLellan Institutional Web Management Workshop, July 2007 Hello! - allinthehead.com, microformatic.com - group lead for web standards project - also work at Yahoo! I’m not speaking for Yahoo! today.

Can your website be your API? Can your website be your API? - attention grabbing headline that needs some unpacking Less sensationally, it could be asked like this...

Could my website be an API? Or perhaps more fully ...

Can I add enough semantic information to the pages I already publish so that they could replace the function of a dedicated API? Whichever way you phrase it, the answer is the same...

Yes

Yes and no

Data is dying. All over the web data is dying. We’re all publishing masses of content online with a relatively low-fidelity markup language - HTML. Whilst HTML offers us something in terms of semantics, in the grand scheme of things it’s not much at all. Let’s take a look at an example.

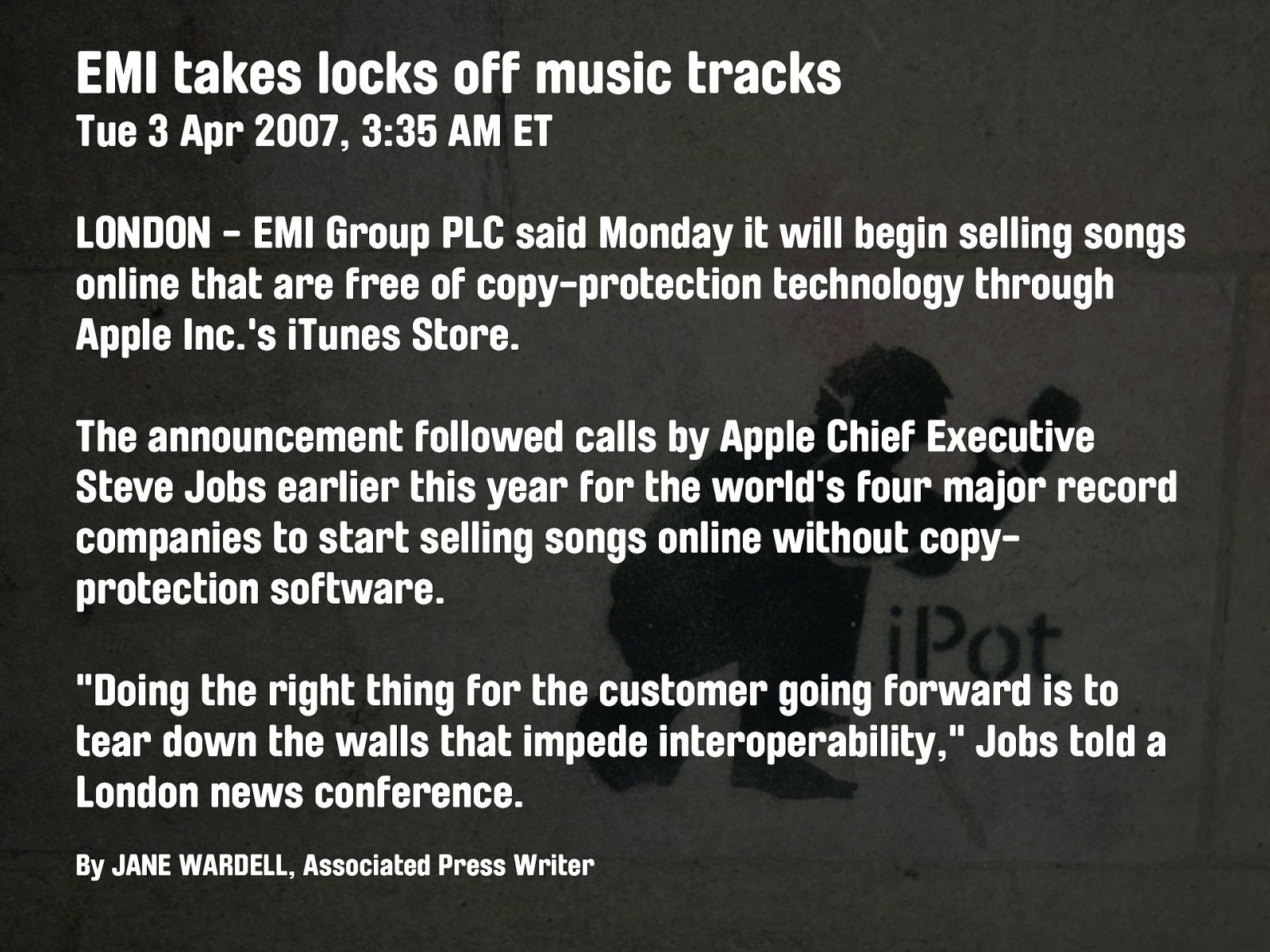

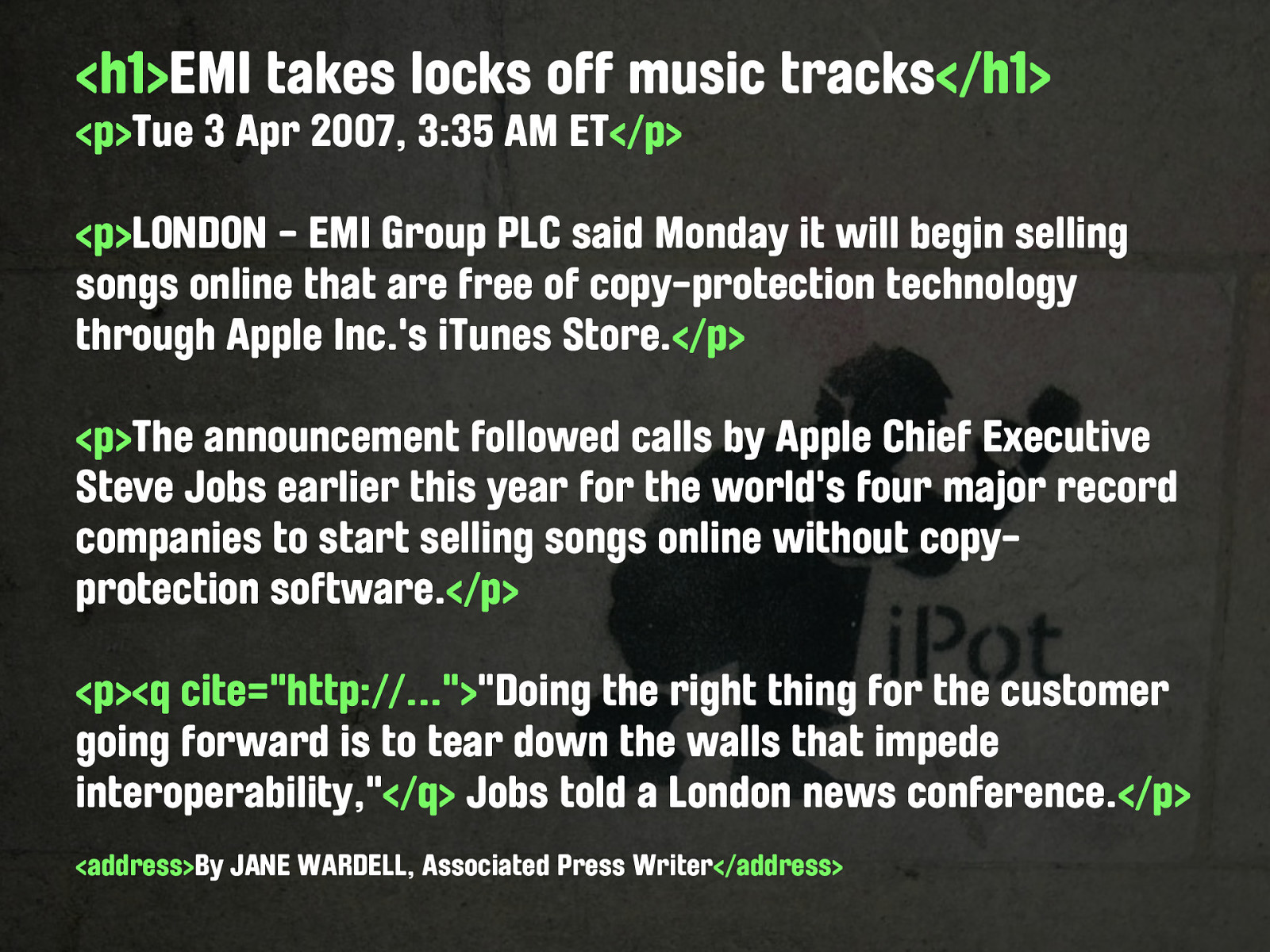

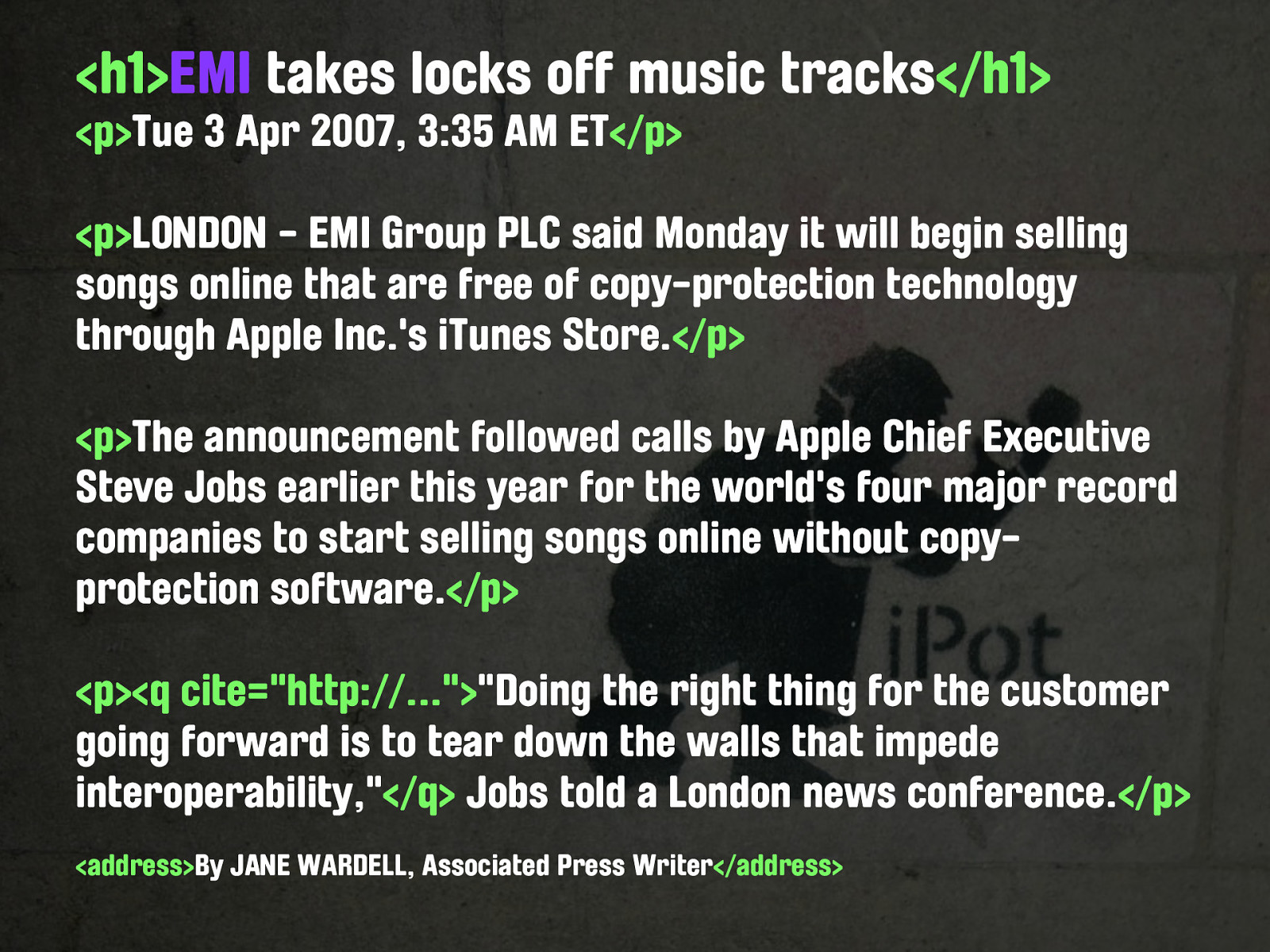

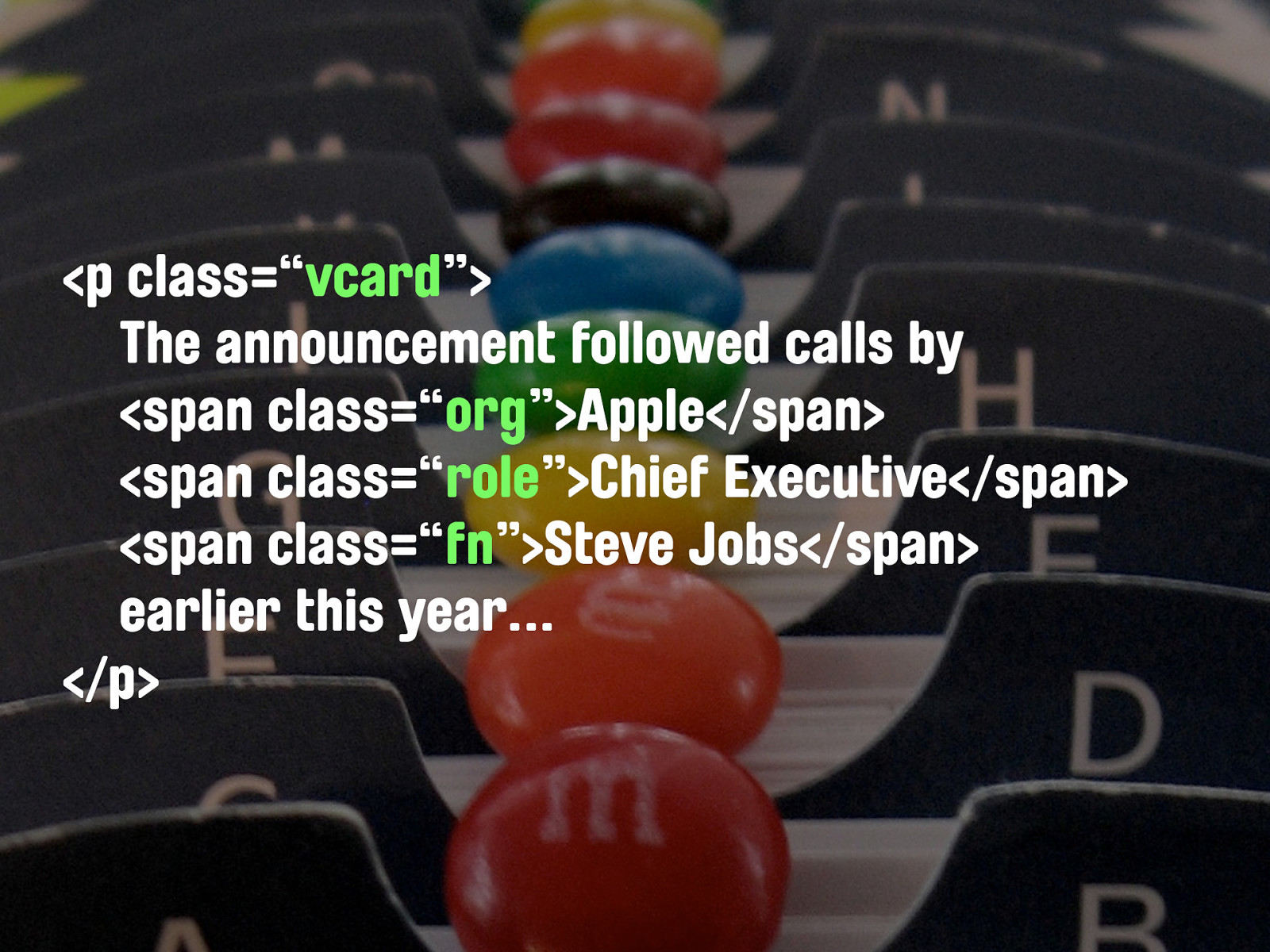

EMI takes locks off music tracks Tue 3 Apr 2007, 3:35 AM ET LONDON - EMI Group PLC said Monday it will begin selling songs online that are free of copy-protection technology through Apple Inc.'s iTunes Store. The announcement followed calls by Apple Chief Executive Steve Jobs earlier this year for the world's four major record companies to start selling songs online without copyprotection software. "Doing the right thing for the customer going forward is to tear down the walls that impede interoperability," Jobs told a London news conference. By JANE WARDELL, Associated Press Writer This is a news story from back in April when Apple announce that some of the music from their iTunes Store would be sold DRM-free.

Article Date Author Location Person Role Company So we have all these different types of data in that one snippet of a news article that is dying as soon as it’s published. Because we have no way of expressing those types of data in HTML the semantics - the meaning - is lost. It’s like publishing a 256 colour GIF of a high res photo. We broadly get the shape, but the detail is lost. This is the problem that microformats are attempting to solve.

Article Date Author Location Person Role Company hAtom Articles, with their respective dates and authors can be expressed in the document with a microformat called hAtom. As the name would suggest, this is based on the familiar Atom feed format, but implemented in HTML.

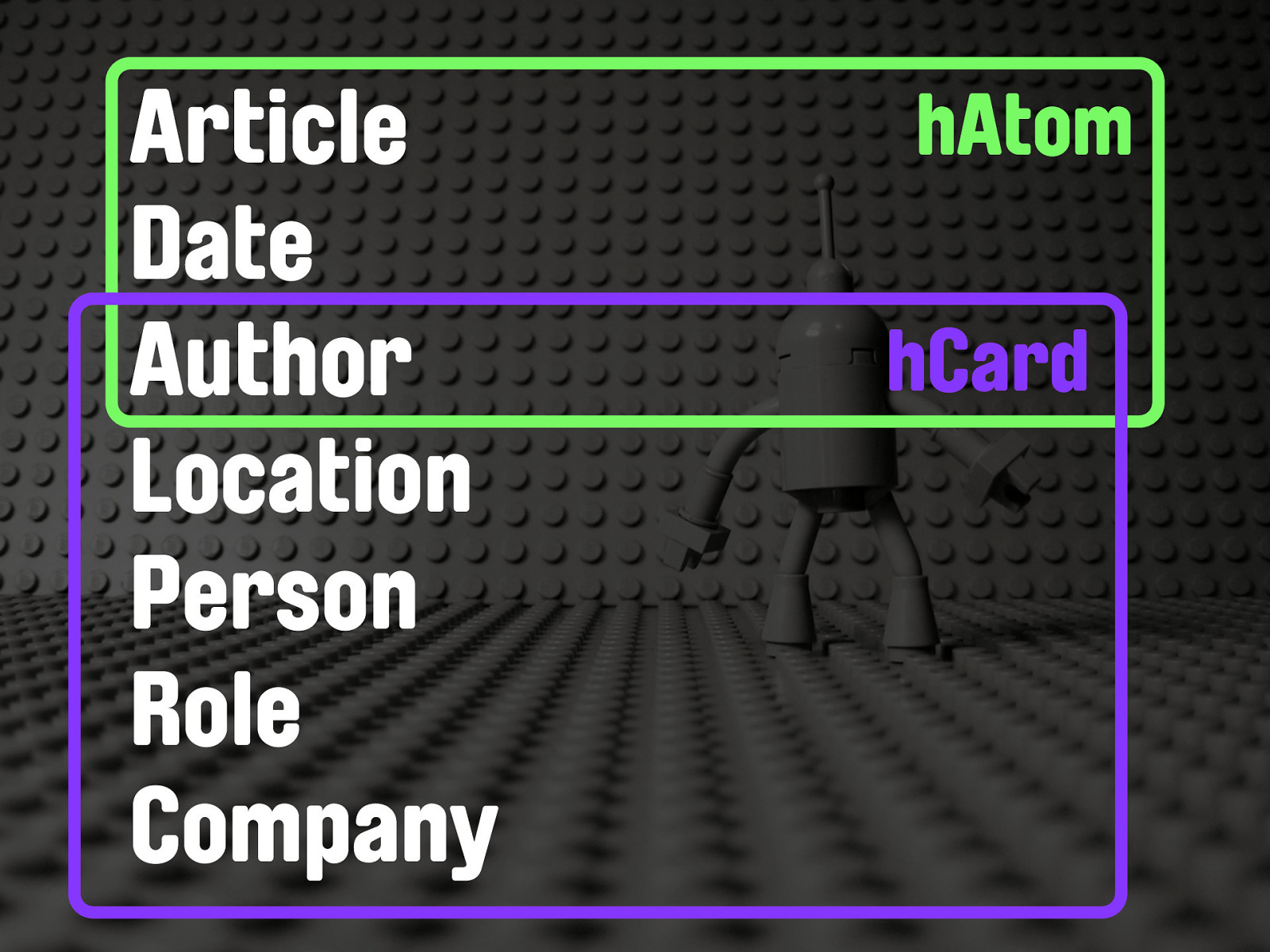

Article Date Author Location Person Role Company hAtom hCard Similarly, people, roles, companies, addresses and so on can be expressed as an hCard - which is an address card microformat based on the popular VCARD standard. An author is just a person, of course, and so hAtom reuses hCard to express its author.

microformats So that’s the problem - but what actually are microformats, and how do they work inside HTML? How do we mark this data up? Without getting to masses of depth, let’s look at how a few common data types can be marked up using microformats.

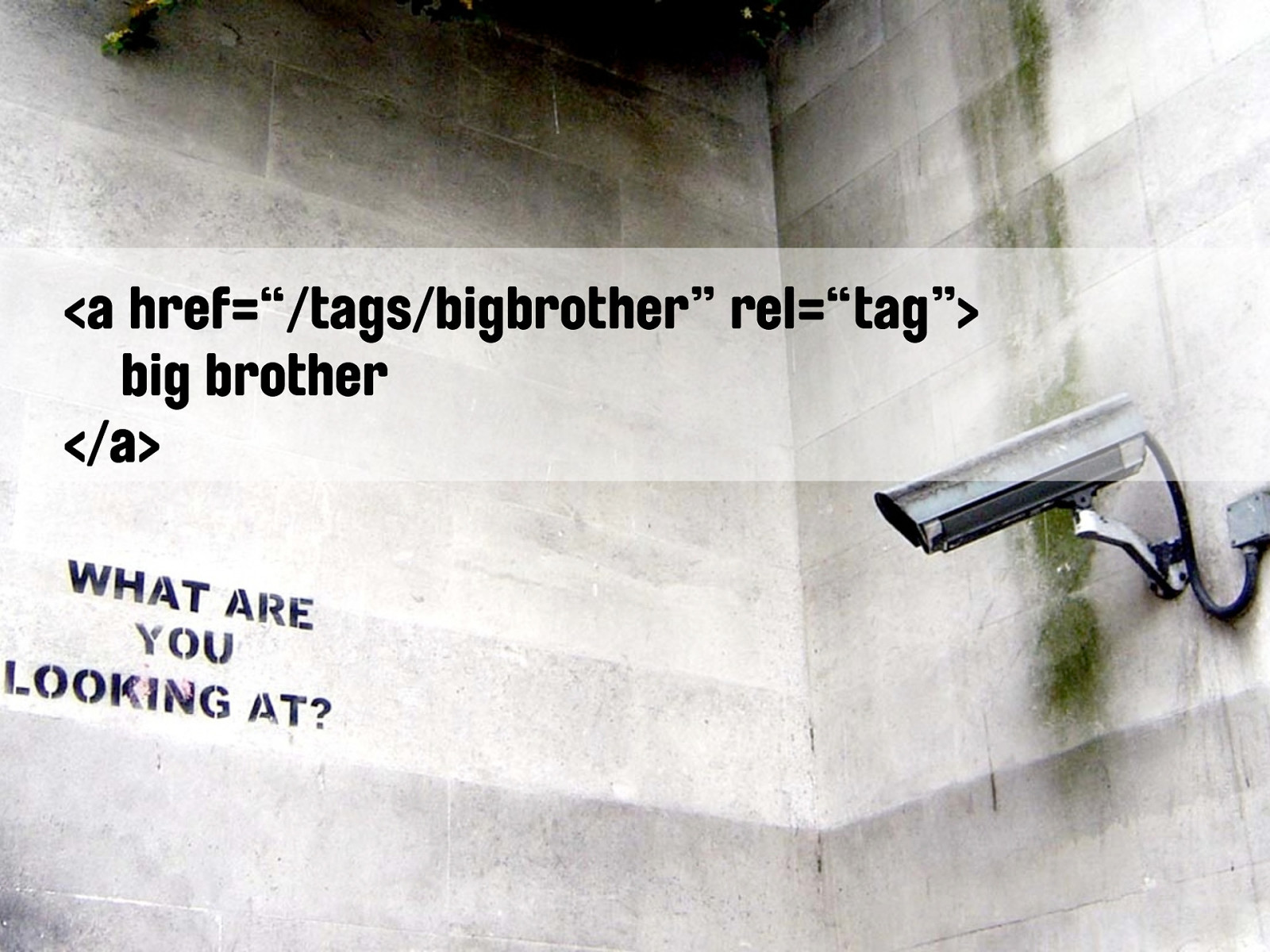

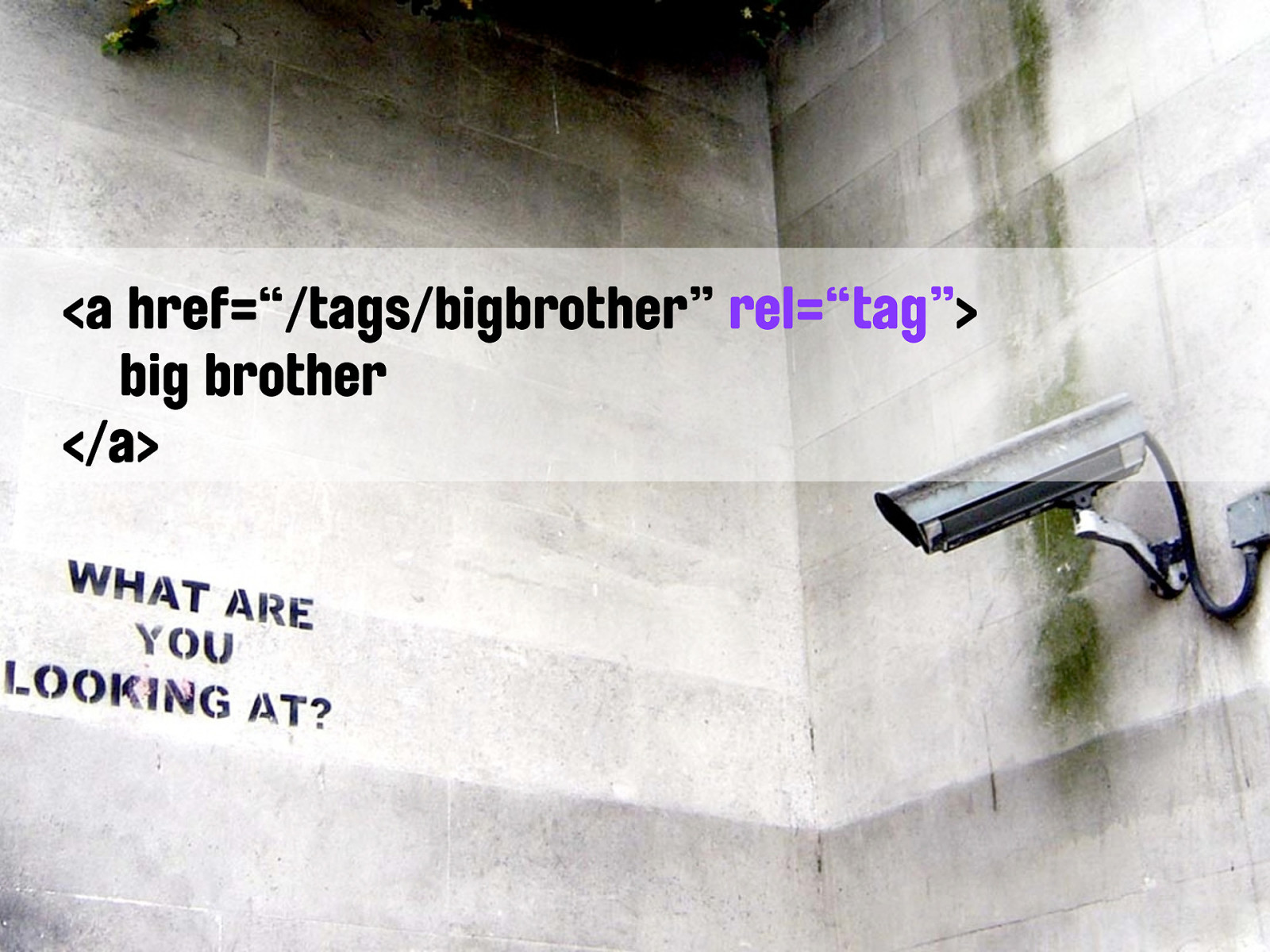

rel-tag for tags Tags are an increasingly common way of applying rough categorisation to objects, free from the formal structures and taxonomies associated with traditional categorisation. It’s useful to be able to identify tags in a page - distinct from other regular links - as they give us insight into the item the tag applies to. So we have a microformat called rel-tag.

<a href=“/tags/bigbrother” rel=“tag”> big brother </a> As you can see, this is just a regular A element - a link. By using the REL attribute of the A element, we can mark it as a tag.

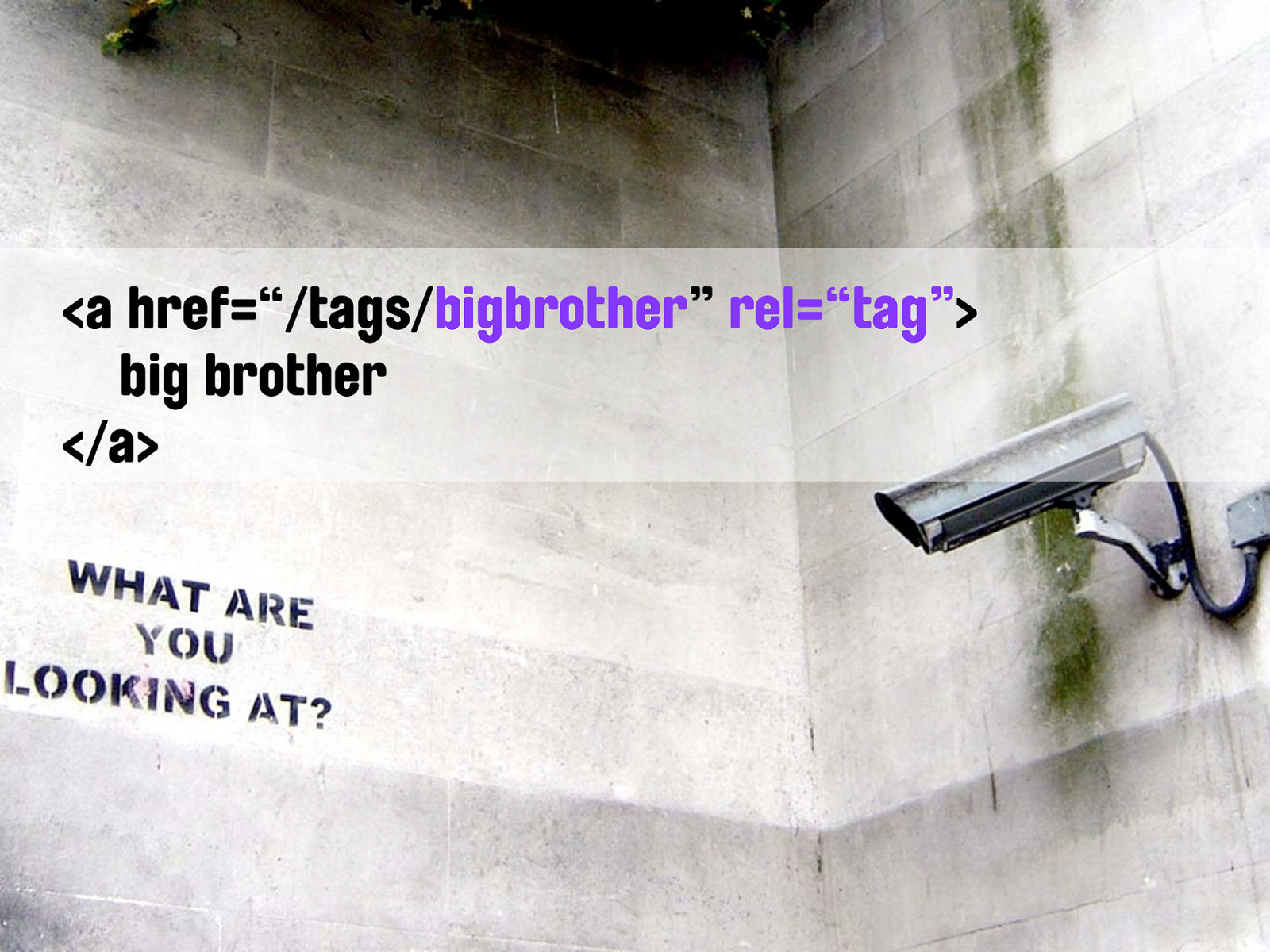

<a href=“/tags/bigbrother” rel=“tag”> big brother </a> REL specifies the relationship between the current page and the page we’re linking to. Therefore it makes sense that a tag always links to a page defining that tag - a pattern I’m sure we’ll all familiar with.

<a href=“/tags/bigbrother” rel=“tag”> big brother </a> In the rel-tag microformat, it’s the last segment of the URL that is the definition of the tag, not the link text itself.

<a href=“/tags/bigbrother?foo=bar” rel=“tag”> big brother </a> This excludes any query string ....

<a href=“/tags/bigbrother#wtf” rel=“tag”> big brother </a> ... or document fragment identifiers. This is what we call an ELEMENTAL MICROFORMAT. It’s the simplest form of microformat, and is often reused by more complex, COMPOUND MICROFORMATS. Let’s look at some examples of compound microformats next.

hCard for address cards hCard is a microformat for describing name and address information. It’s based on the common VCARD standard, which is what most address book software, PDAs and mobile phones used. Because it’s based on VCARD, translating an hCard in a web page into something that can be added to your address book is quite easy, and begins to hint at just how useful saving this data can be. Here’s how it’s implemented.

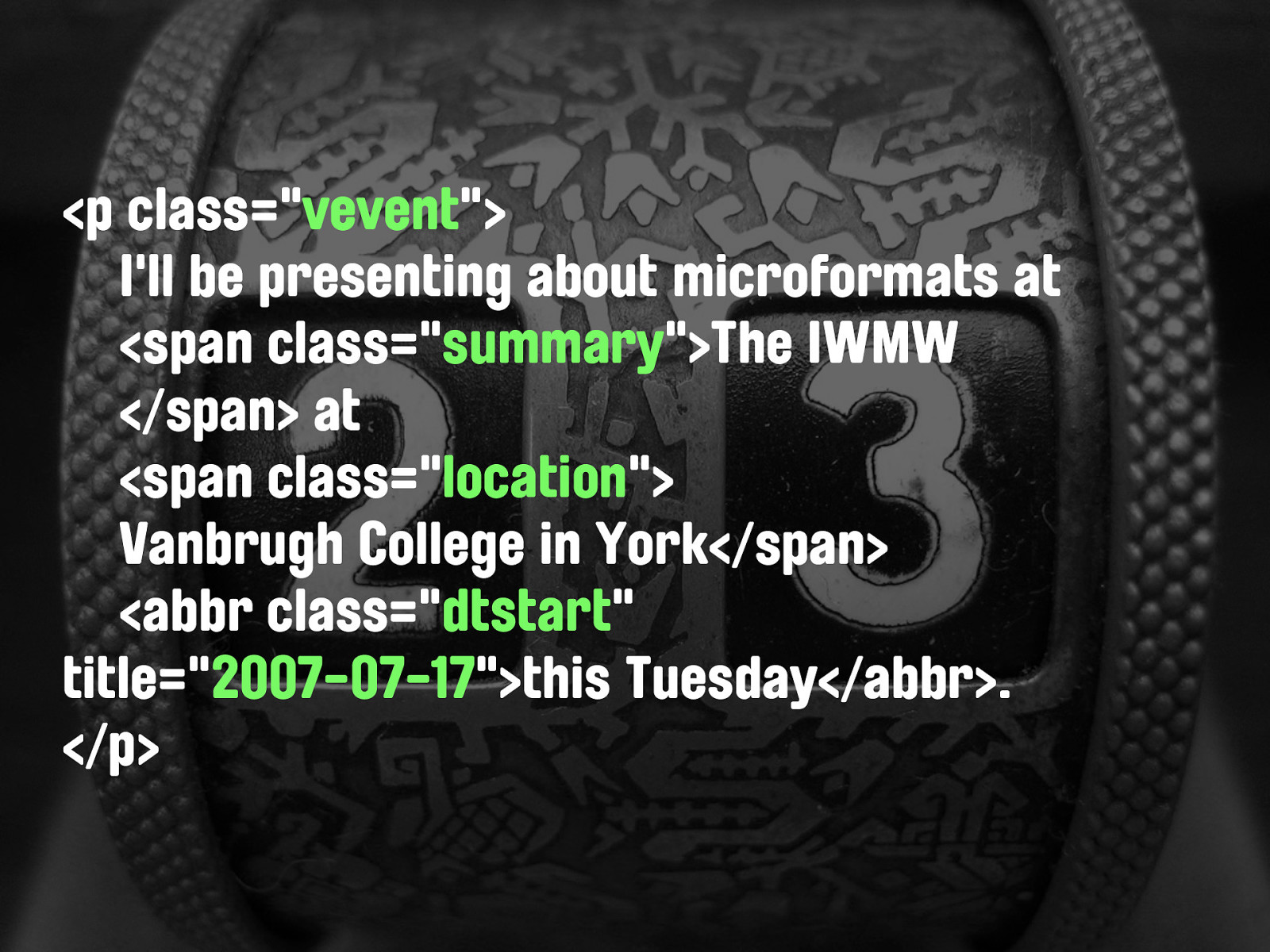

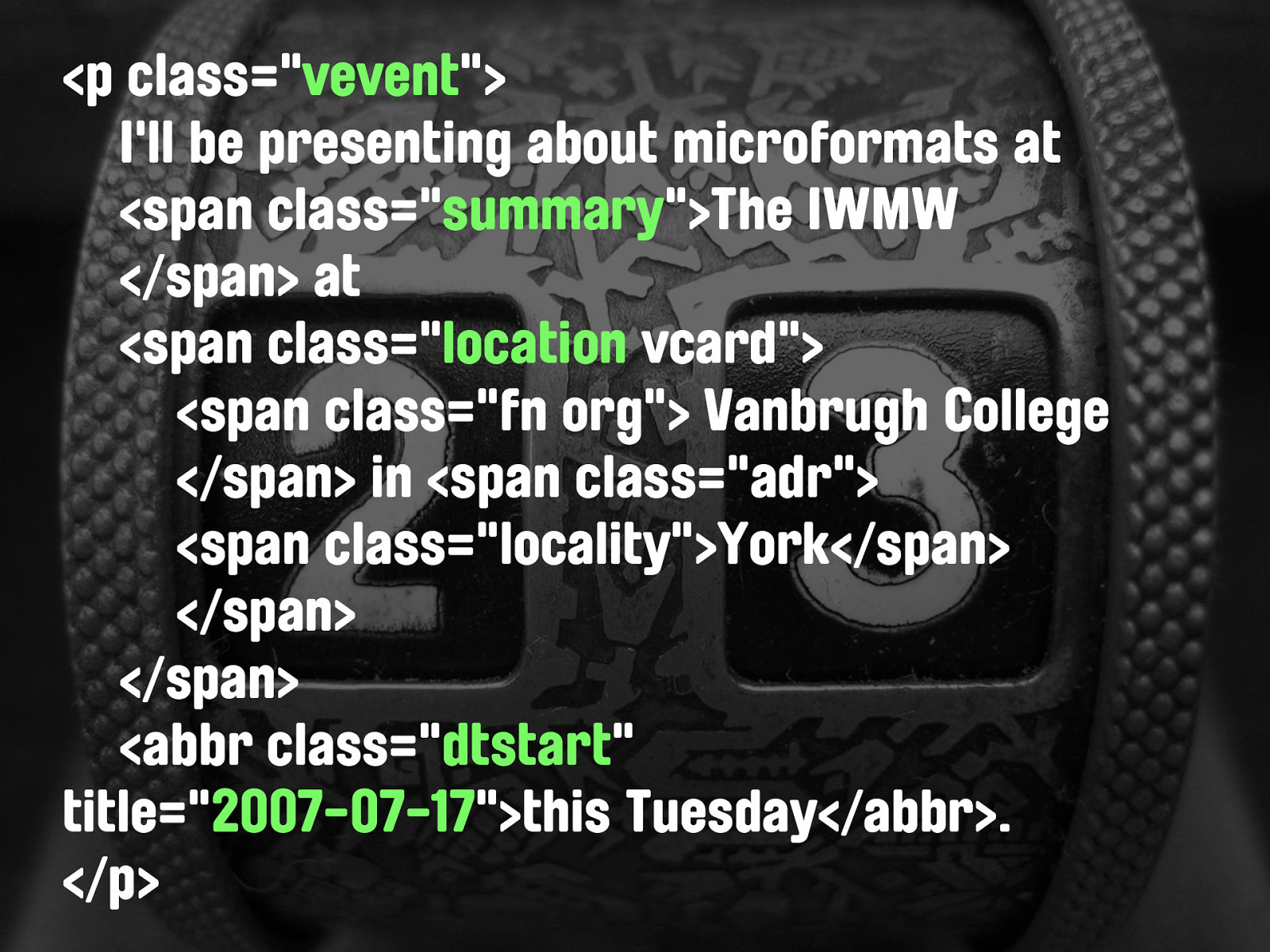

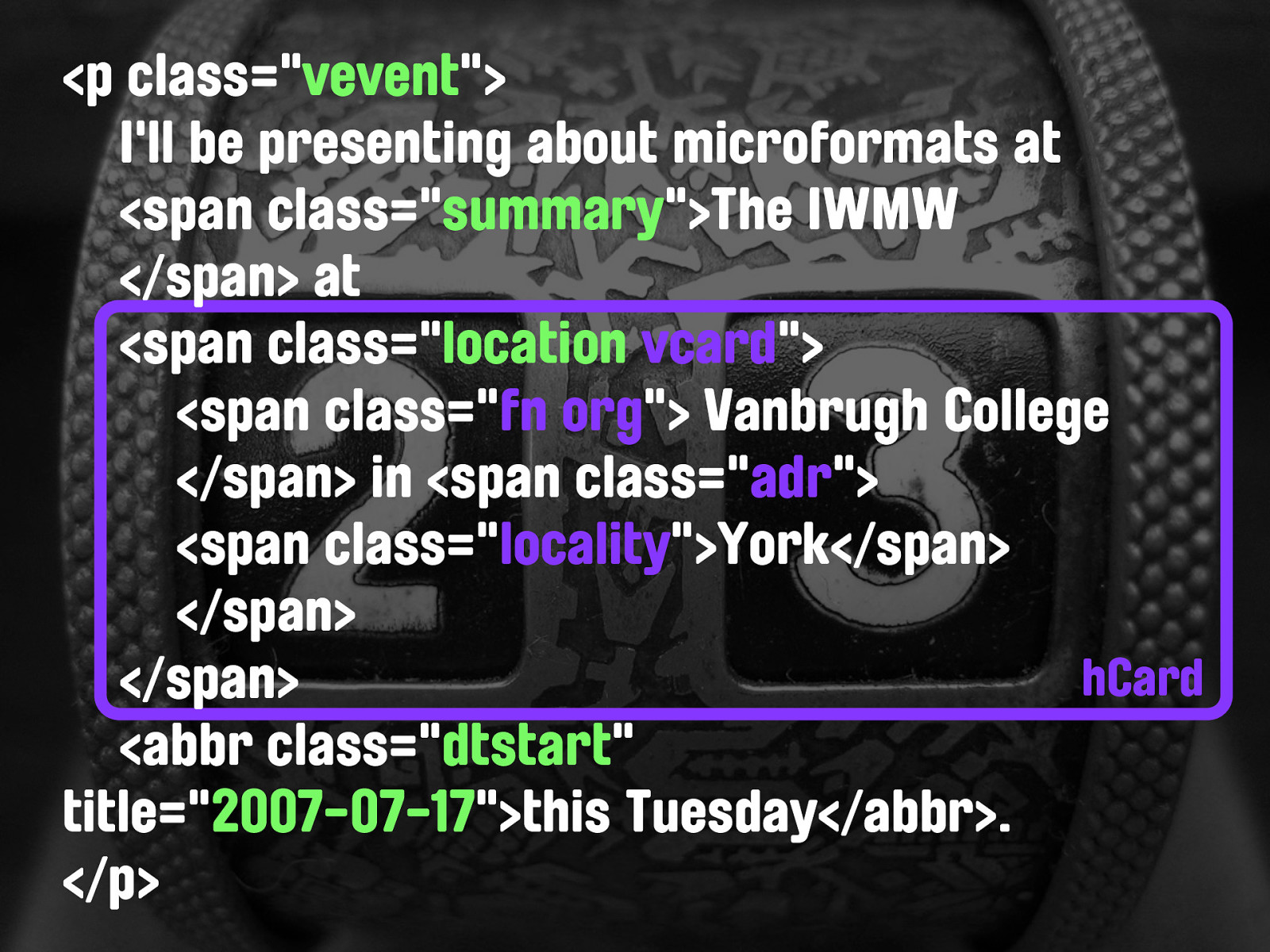

hCalendar for events

Brain > Code So we’ve heard a lot about microformats and how they enable us to mark up data in a meaningful way. We do this so that the information becomes useful not just to complex parsers - like the human brain - but to relatively simple parsers, such as software. Software, of course is derived from a very small subset of the human brain, and therefore can't currently encompass the extreme complexity of the rules and processes the human brain goes through when trying to make sense of something such as an arbitrary list of random words. Spotting something like a company name in a list of random words for example, is quite easy for us but more far more complex to identify all those rules and codify them.

Fork handles? An interesting example of such a situation is with telephone technologies, and in particular speech recognition. There have been all sorts of efforts in the past to get speech recognition working well across phone systems. I imagine most of us have at some point played around with speech recognition software of some kind. Maybe that's PC dictation software, or maybe just an annoying IVR system. They don't tend to be so great at recognising anything but the most straightforward patterns of speech. The human brain, as a complex parser, takes very little time to adjust to different voices - even the strongest of regional accents are typically understandable within a few moments of listening to a person's voice. Speech recognition software - until very very recently - has found it hard to get any kind of acceptable accuracy levels even with RP. Mix in the poor audio quality of a phone signal, and this becomes an even tougher task.

File > Open A few years back I was at college with a guy who'd been helping his housemate install and configure some speech recognition software on his housemate's PC. My friend spent quite a bit of time fine tuning the program whilst his housemate was out at lectures and managed to get it working with a pretty good level of accuracy. So you can imagine my friend's surprise when his housemate reported that he was getting absolutely nowhere with the software, despite persistent efforts. So my friend tried it himself "File, Open" and it worked just fine. The housemate tried again "File, Open" and nothing happened. Thinking for a brief moment the housemate tried again in my friends Geordie accent, and lo and behold, it worked.

(shameless) So whilst it's usually possible to get CLOSE to the meaning of things by having a machine attempt to process the material the human brain works with directly, it's often far more effective, efficient and reliable to provide dedicated information that a machine can understand.

For telephone systems, this resulted in the fax machine. A fax machine works by turning data signals into audio signals which can be sent over a regular audio phone line and turned back into data by the fax machine at the other end. Rather than trying to have machines understand a human voice, the machines only need to understand other machines, over the same type of line.

beep Fax machines are the APIs of the telephone world. They're a provision for machine to machine communication in and out of your company or organisation. This has big benefits, as larger amounts of data can be transferred much quicker and with greater accuracy than if there was a manual process involved.

Tel: +44 (0) 1234 432 432 Fax: +44 (0) 1234 432 433 They're not without their downsides though. Fax machines are hateful, evil machines that will eat your soul and then spit it out as an ad for a cheap car purchase plan. Once a company decides to have a fax machine and enable customers to communicate with them via fax, the company has to start publishing a different line number for faxes. This means that customers then have to go through the extra cognitive step of figuring out which damn number to call. Doesn't sound like a particularly heavy cognitive process, does it? Or so you'd think unless you've ever had a desk in an office where you're sat near the incoming fax machine.

So in the same way, your web app API is a way for other machines to talk to the machines that run your application, but as a distinct second route in to that application, a route dedicated for machines rather than humans. And like the fax machine, this is not without its costs. Typically, developing an API is in addition to the basic work needed to have your application functional. Whilst if you're clever, parts of your application such as JavaScript code running on the client can make use of that API (and therefore making good use of the work required to build the API - Flickr is a good example), it's likely that most of this work will be above and beyond what's required for your version 1.0.

Mmm APIs! But this is NOT a argument against APIs - far from it. An API is increasingly an essential component for any modern web application. This is an argument to provide that same functionality in a more efficient way. An argument to reuse existing technology and resources in place of building new and spending more. This an argument to make your public facing website your API, and to do so through intelligent use of HTML-embedded data mechanisms like microformats.

Bow-wow Imagine for a moment that fax machines could operate at the sort of high pitches that dog whistles create. Whilst the screeches and beeps would be inaudible to the human ear, another fax machine could be tuned to pick them up. The result being that the audio band to which the human ear is sensitive would remain clear, enabling a normal conversation to take place at the same time on the same line. You could make a hotel reservation AND confirm it in writing during the space of the same phone call. Of course that's pretty daft, not least because a phone line doesn't have enough fidelity to achieve that - it can only just cope with the human voice. A web page is similar. It has higher fidelity than a phone line, as we can include both the human-readable information and basic semantics for machines. That fidelity can be vastly increased, however by adding microformats to the markup. All of a sudden the information we're communicating for humans can be encoded to be understandable - in detail - by machines.

yay. This means that the same page that serves data to your human visitors can serve data to your robotic friends too. What's more, it's the exact same data representation, and not a secondary view into it to develop and maintain. Of course I'm talking about how this can be achieved with microformats, but how does this work in practise? Let's take an example from your favourite social events aggregator and mine, Upcoming.

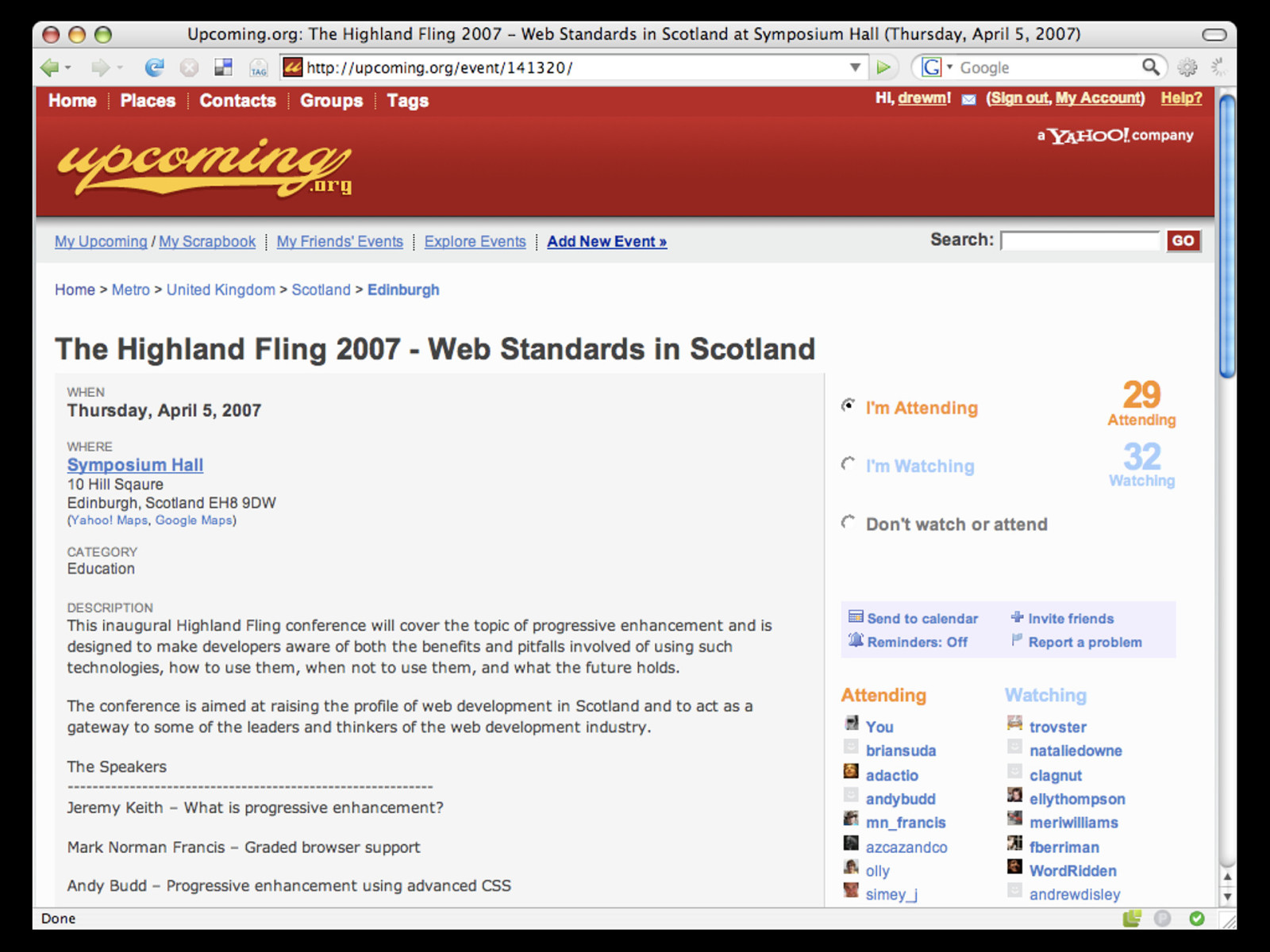

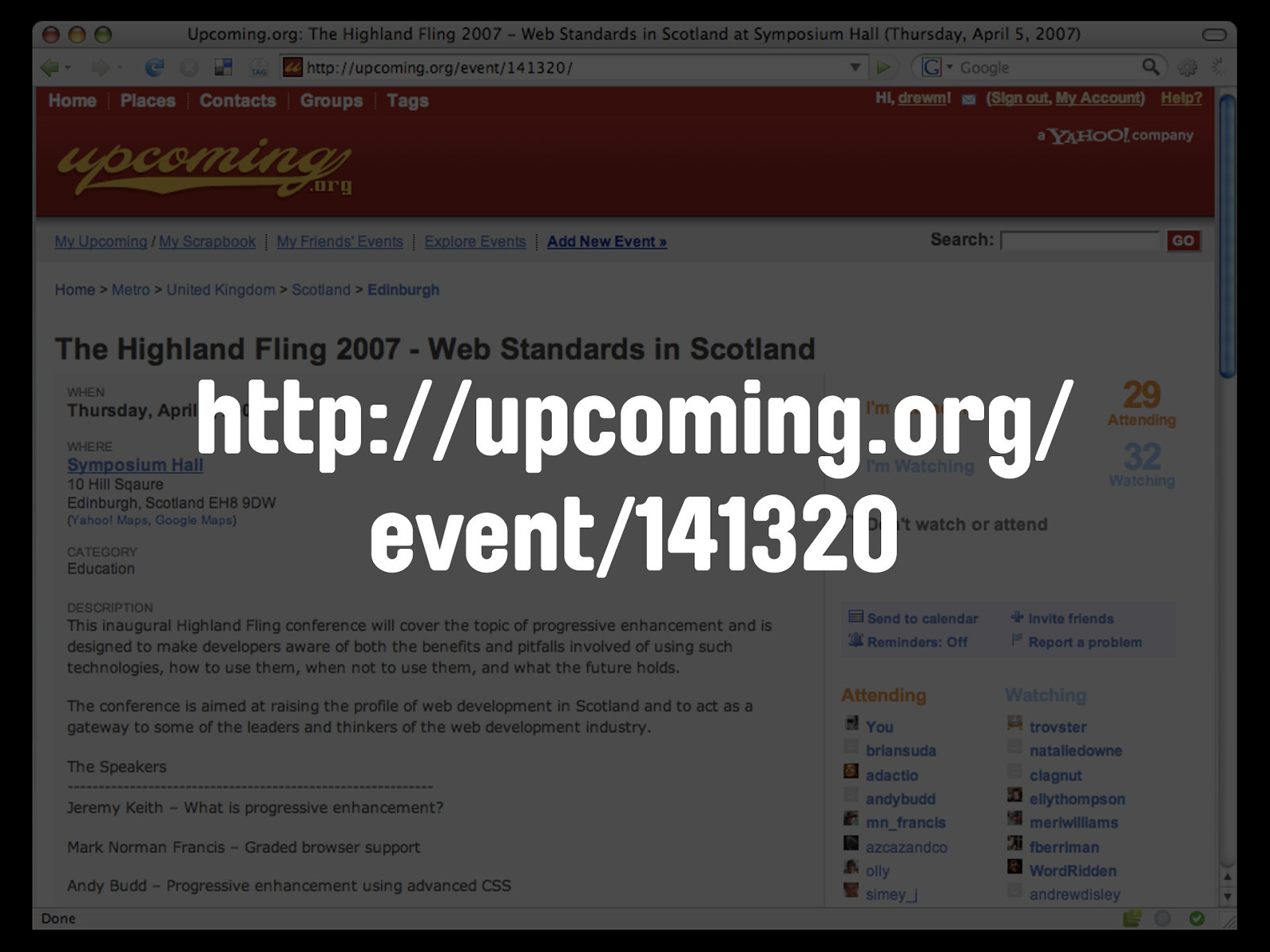

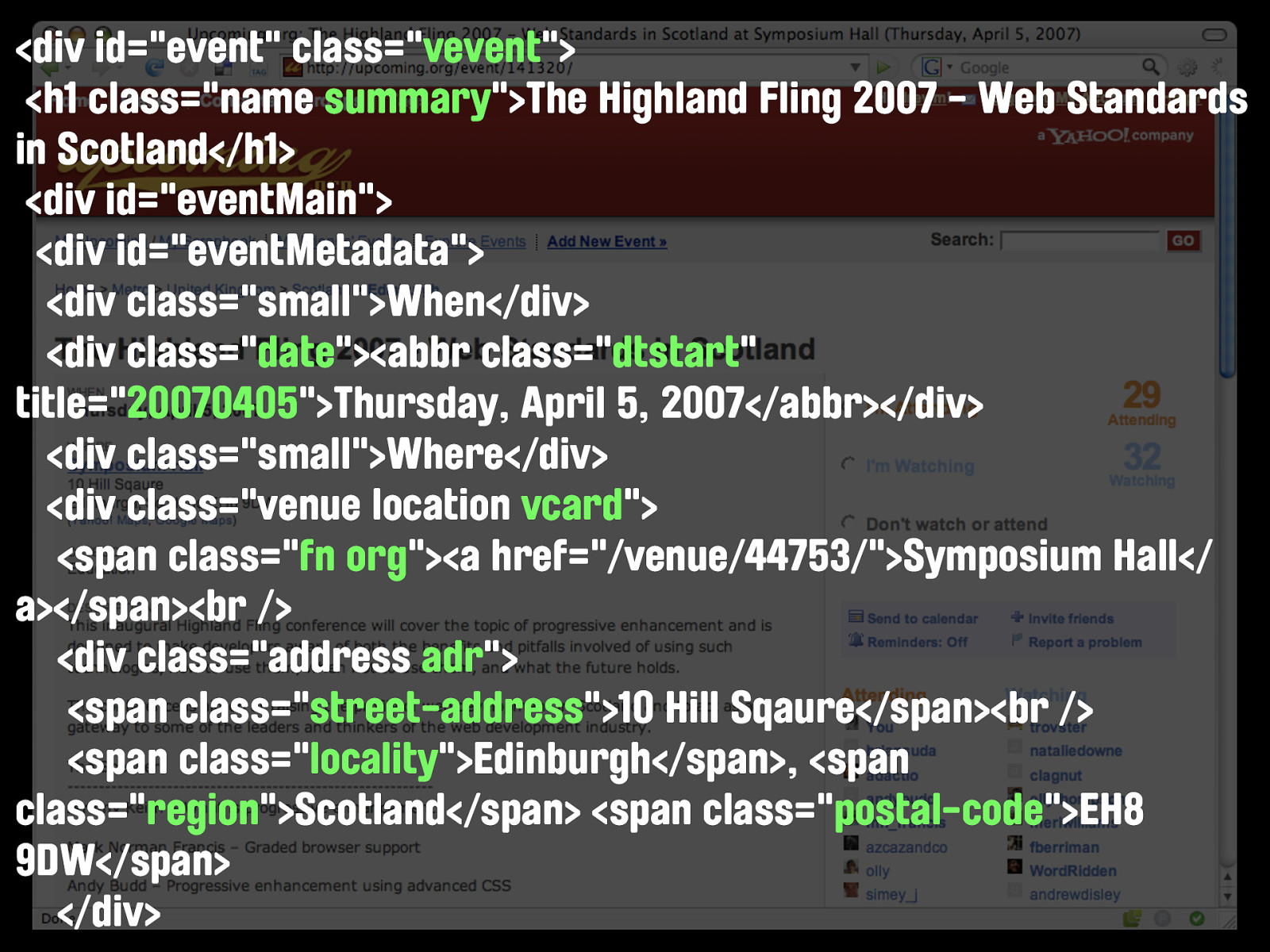

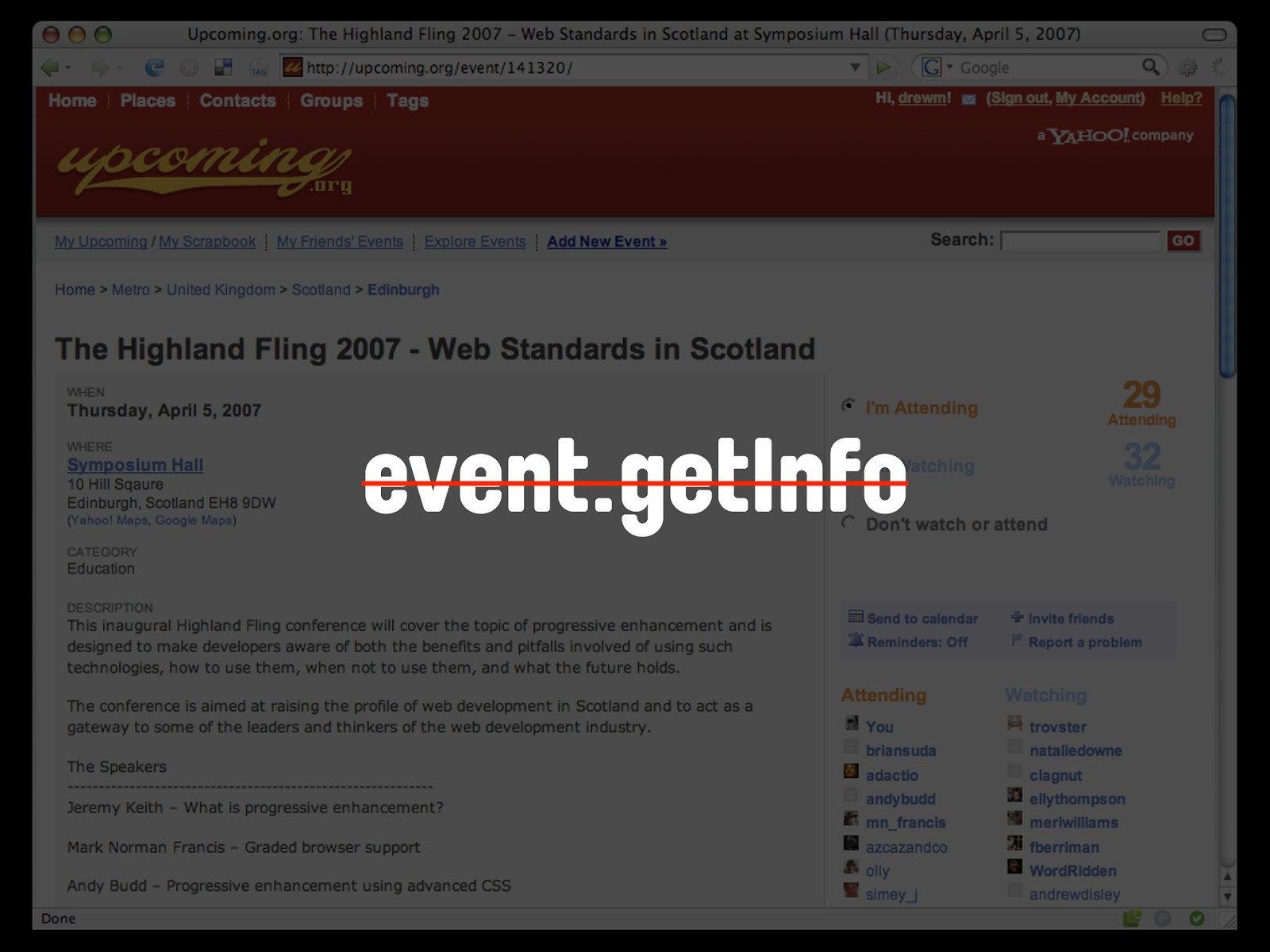

Let's take a simple example of the detail page for an event - like The Highland Fling conference that ran in Edinburgh for the first time earlier this year. If you look at the URI of the page, it tells us a lot of information.

http://upcoming.org/ event/141320 We have the domain name - upcoming.org - followed by the type of object we're asking for - an event - followed by the unique identifier for that event. The corresponding API call for the Upcoming.org API is event.getInfo.

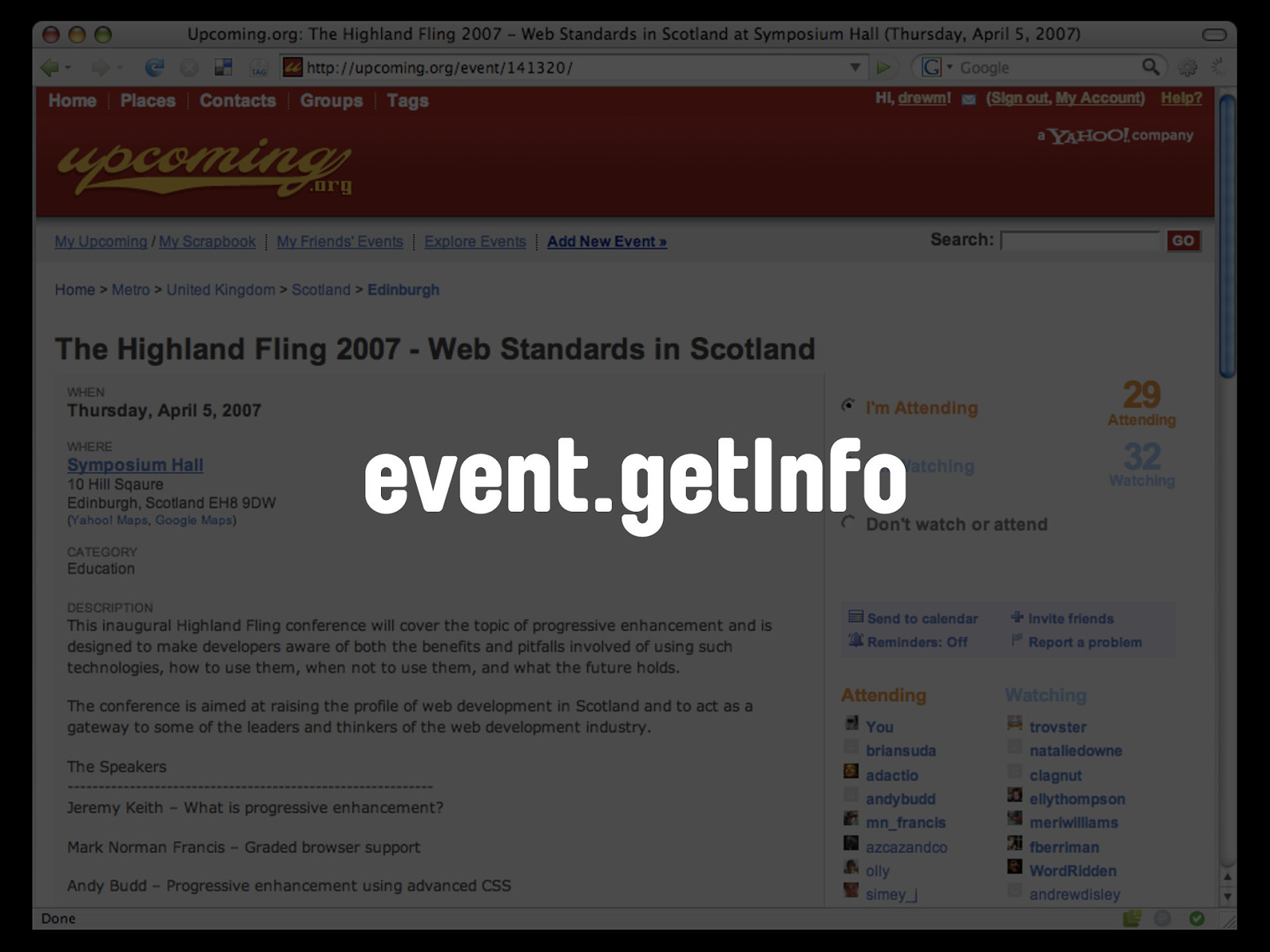

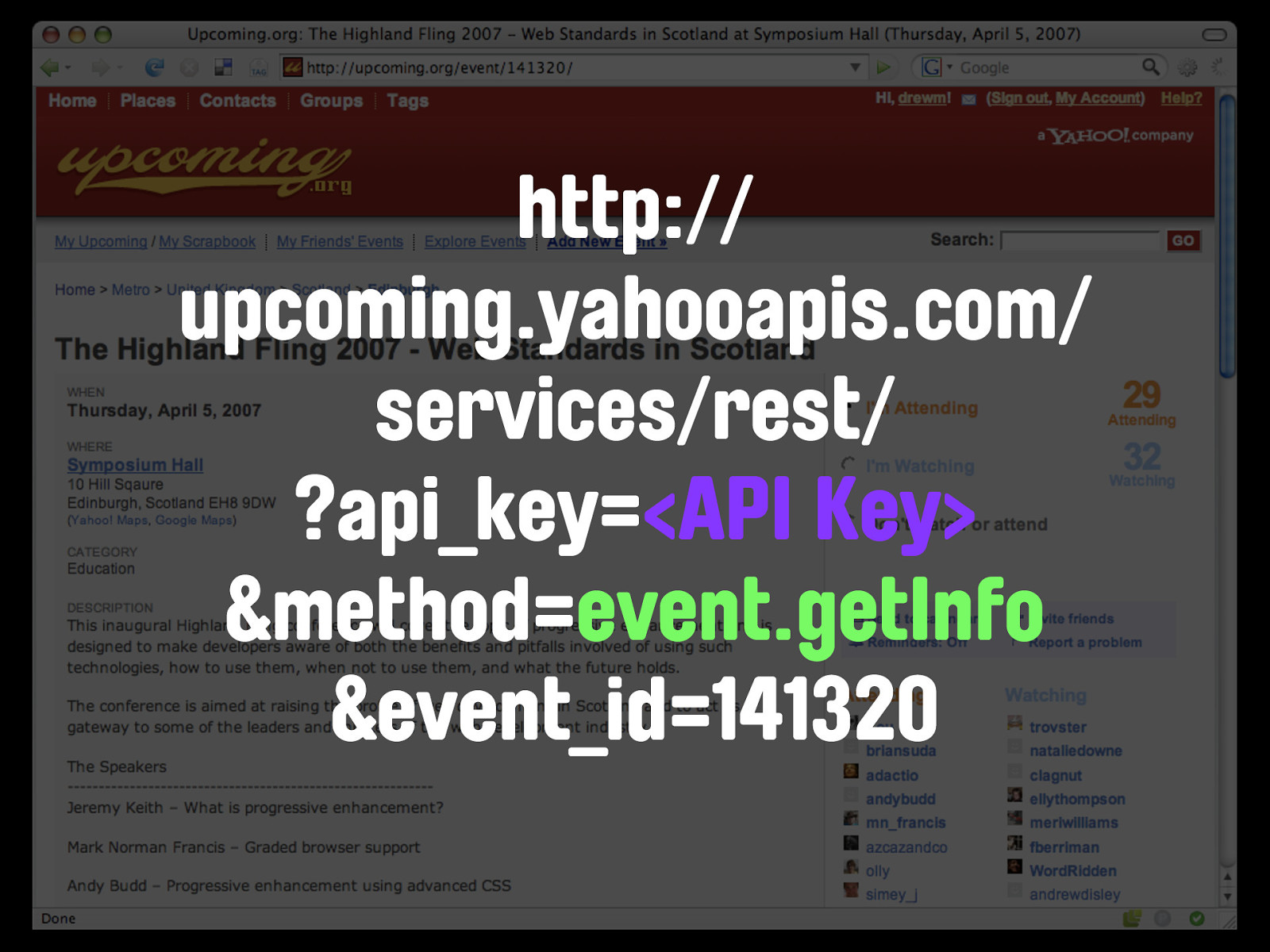

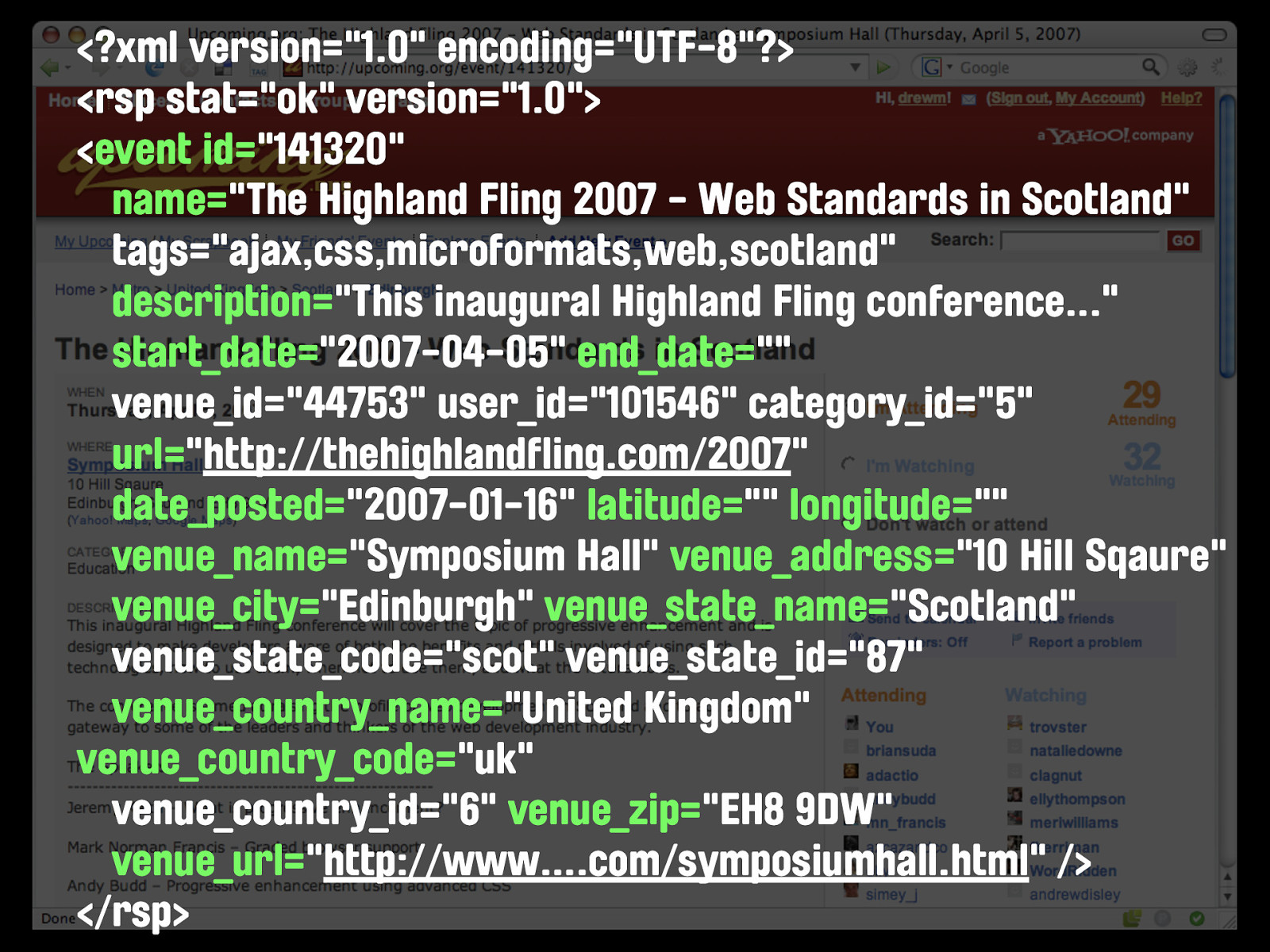

event.getInfo The full HTTP GET for a request against the event.getInfo method looks like this

http:// upcoming.yahooapis.com/ services/rest/ ?api_key=<API Key> &method=event.getInfo &event_id=141320 Noticing any parallels? What we have here is essentially the same data request formatted in two different ways, and resulting in two different representations of the same data. The people of the internets call this a waste. So what if the same resource could be accessed and understood by both regular visitors and machines... One URL, accessing One resource, readable by BOTH types of visitor. Of course, our friends at Upcoming.org are friendly web citizens as well as smart, and have already added the hCalendar microformat to this page.

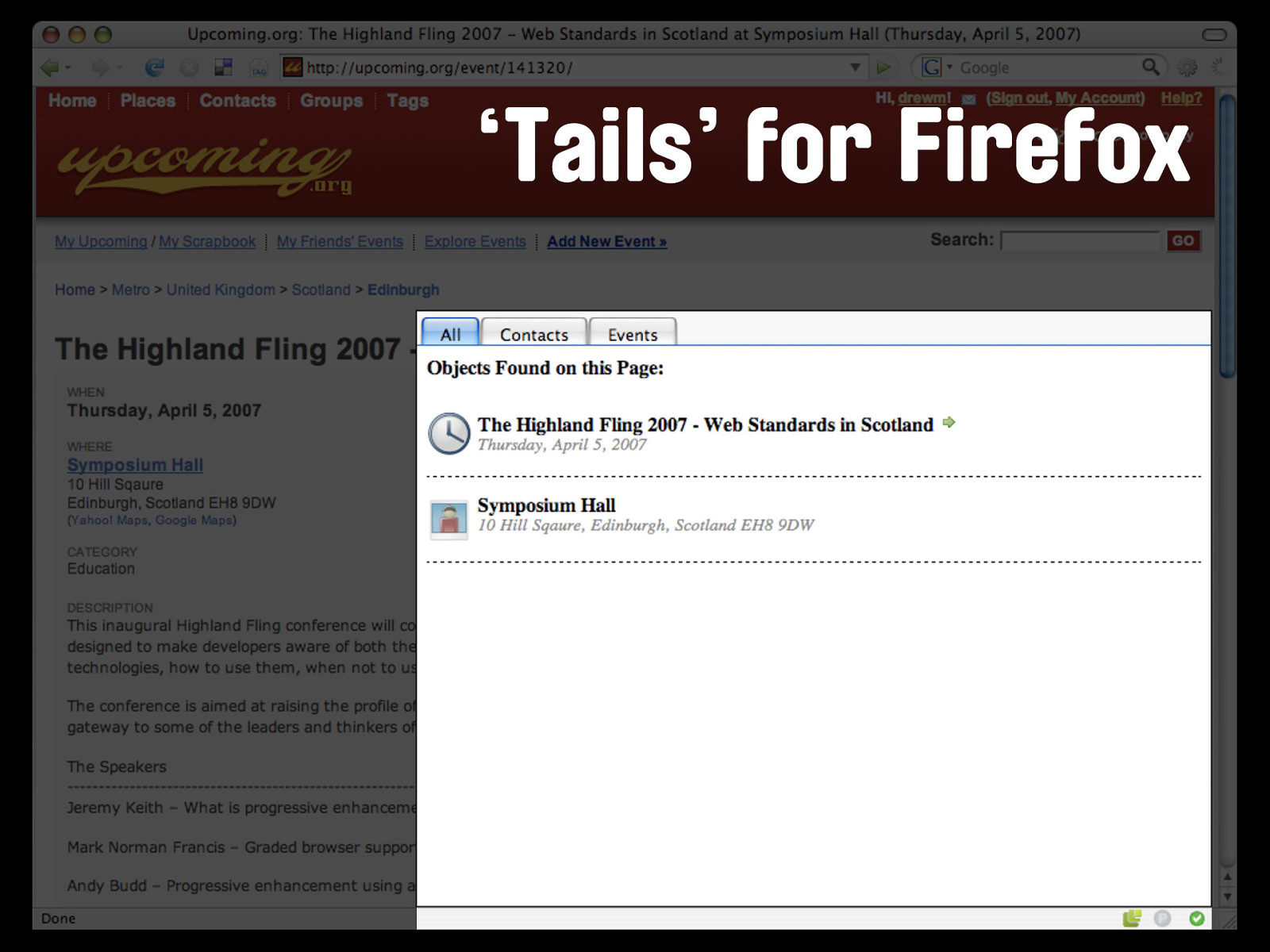

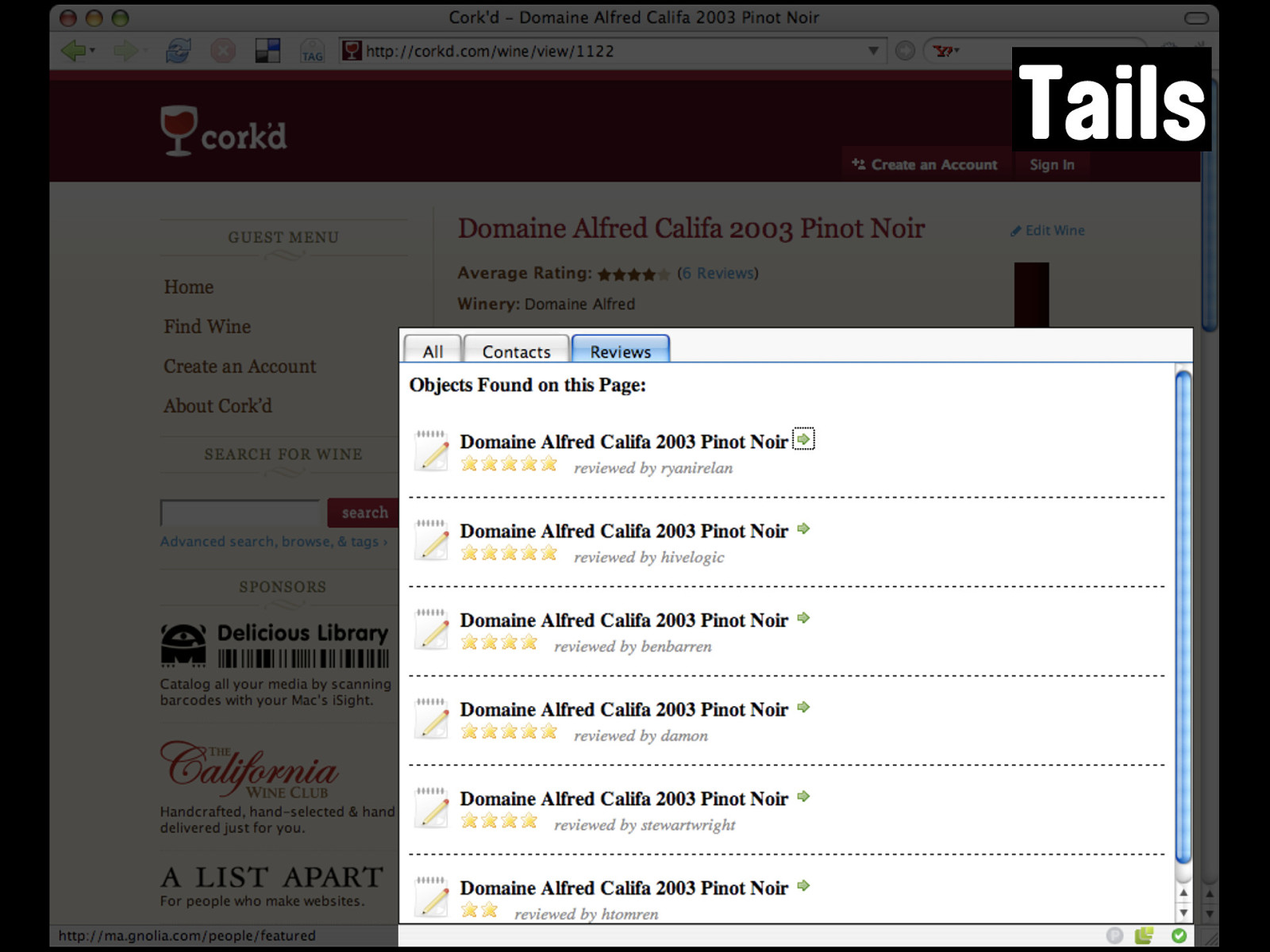

‘Tails’ for Firefox If we run this page through a microformats parser like Tails for Firefox, we can see it finds the data. Similarly, X2V will happily convert this page into an iCal file. If I'd written the hCalendar module for hKit yet, I'd be able to show you that too. It's in the lower-level parsers (the sort that talk between a page and the code you write rather than the page and a user) that the really useful power lies.

event.getInfo event.getInfo is no longer needed, as the same data can be extracted from the page directly. So that's just a very simple example. Unless you've been asleep during every Web 2.0 presentation for the last year, you'll be aware that Flickr has a very powerful and complete API. Surely nothing we can do with microformats could touch the power and might of the Flickr API?

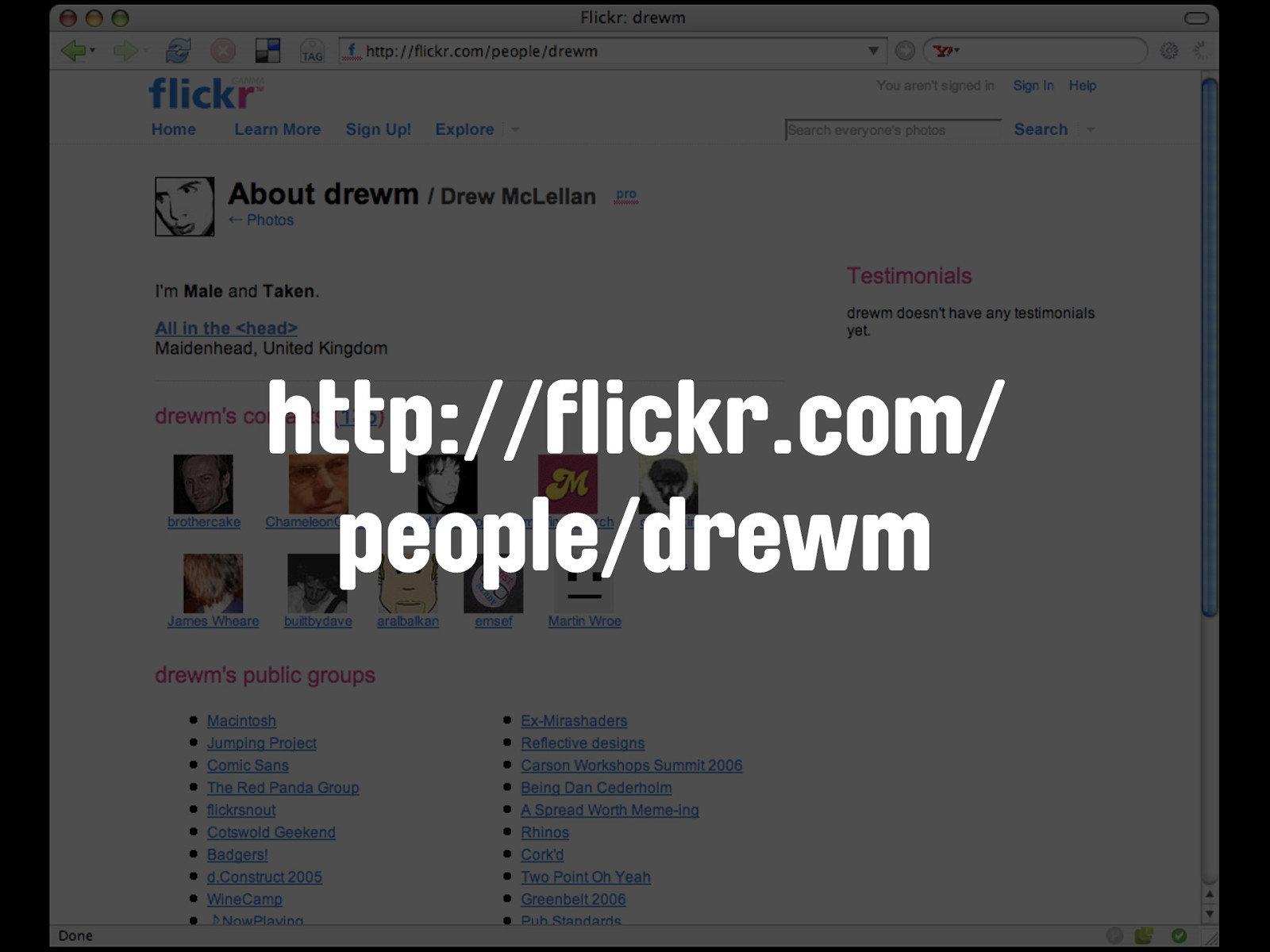

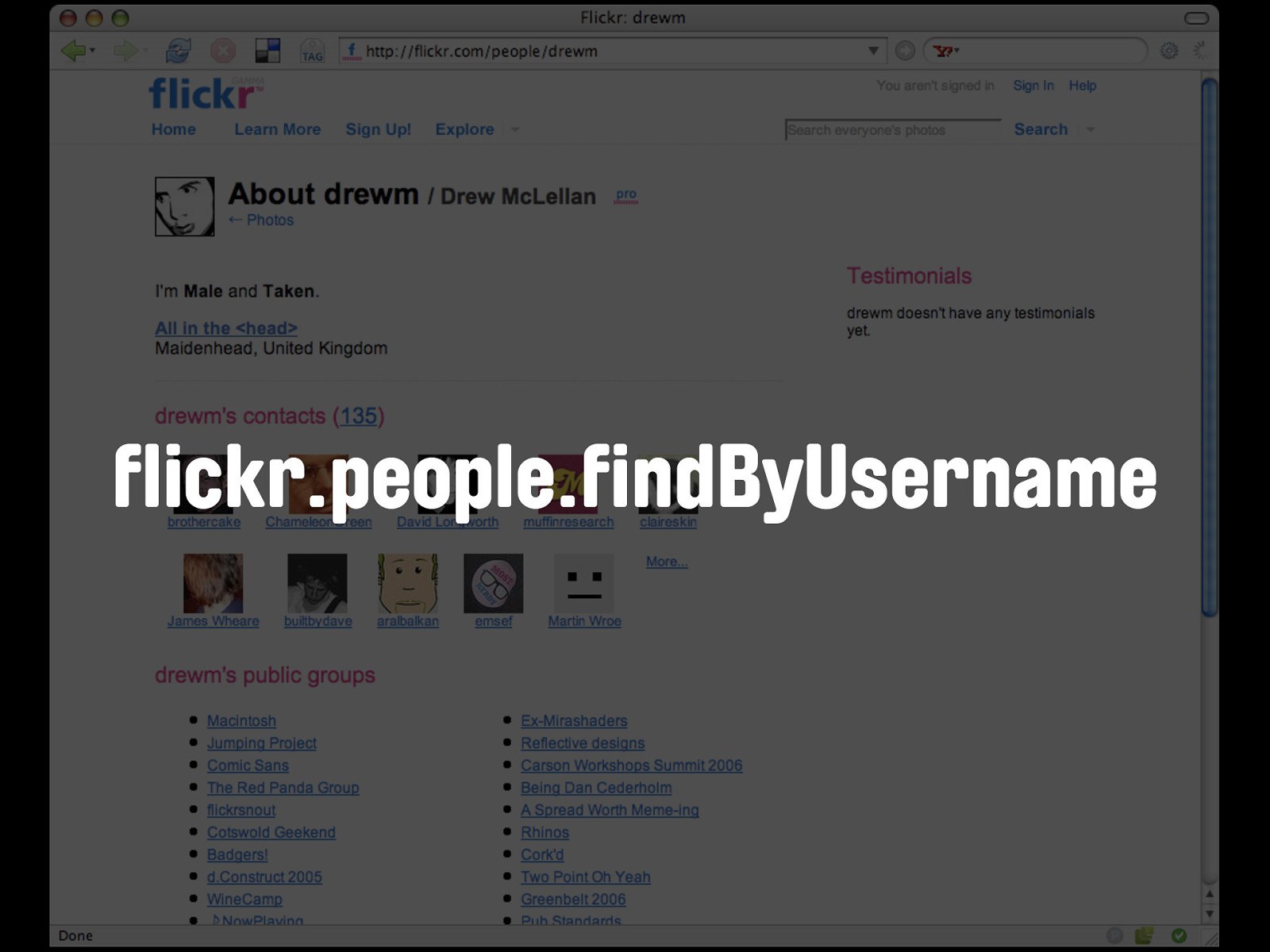

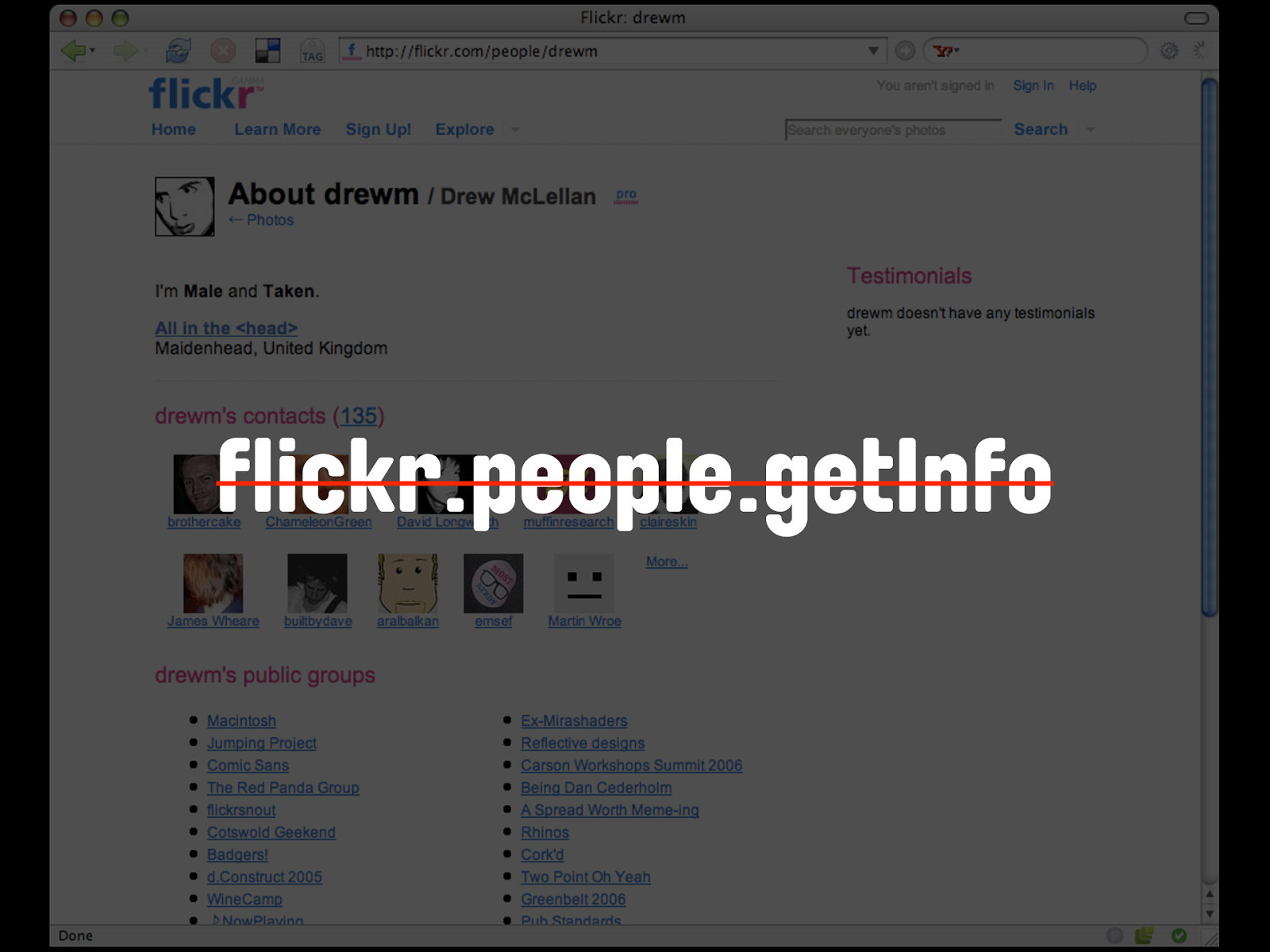

Let's look at the URI for my profile page: http://flickr.com/people/drewm/

http://flickr.com/ people/drewm Just like our example from Upcoming.org, we have the name of the service - flickr.com - the type of object we'd like to retrieve - a person - and the unique identifier for the person in question - the username.

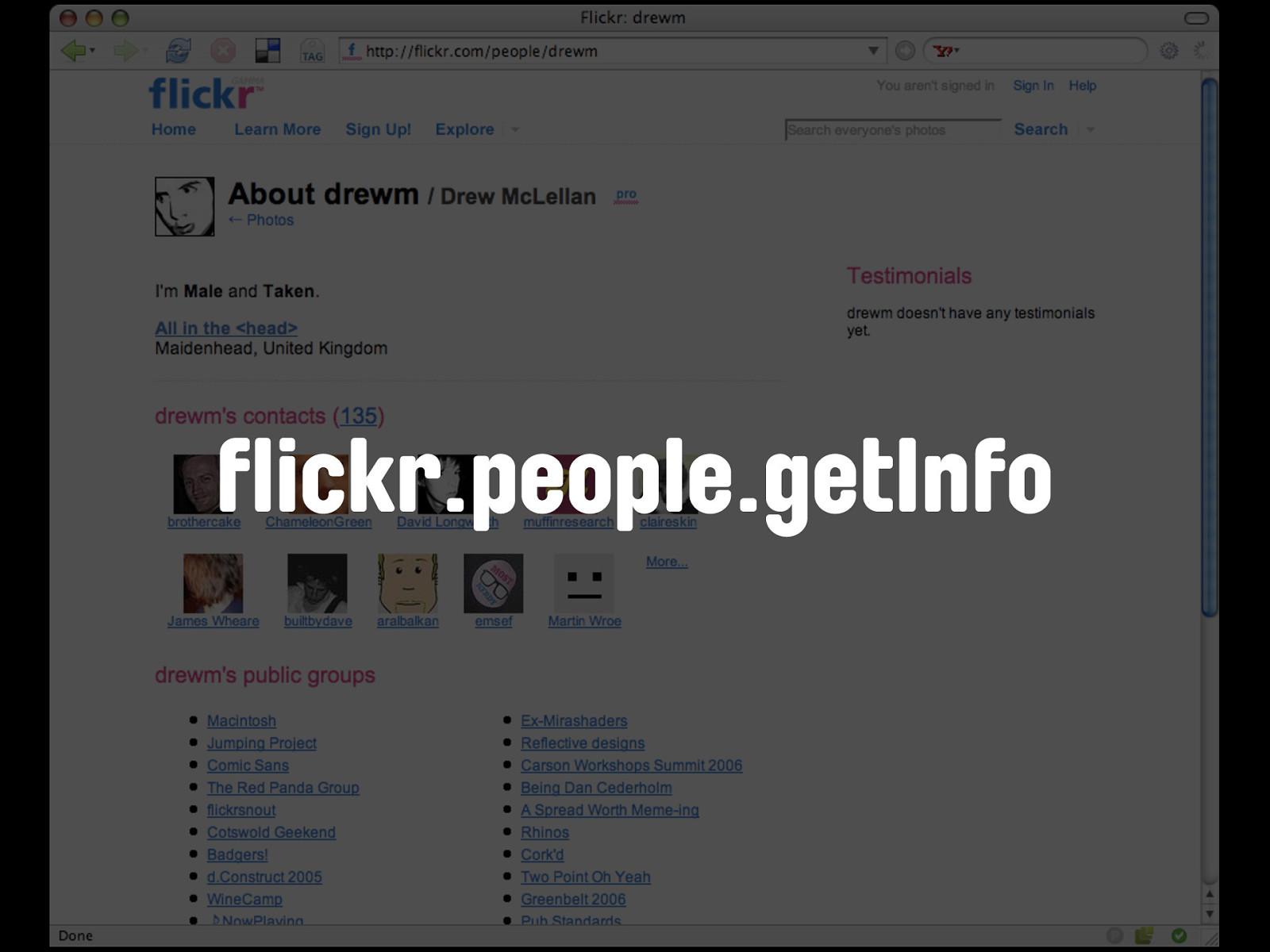

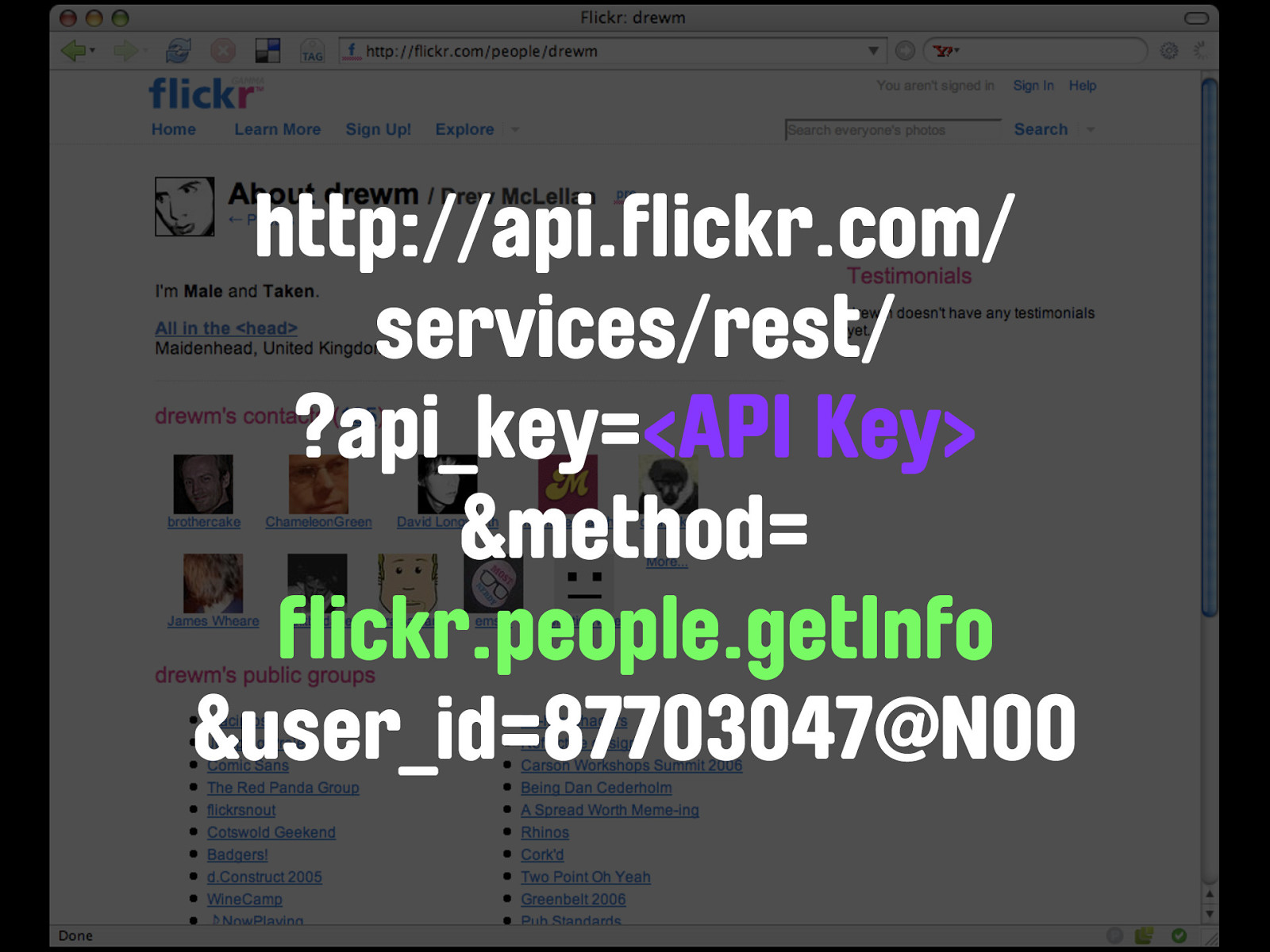

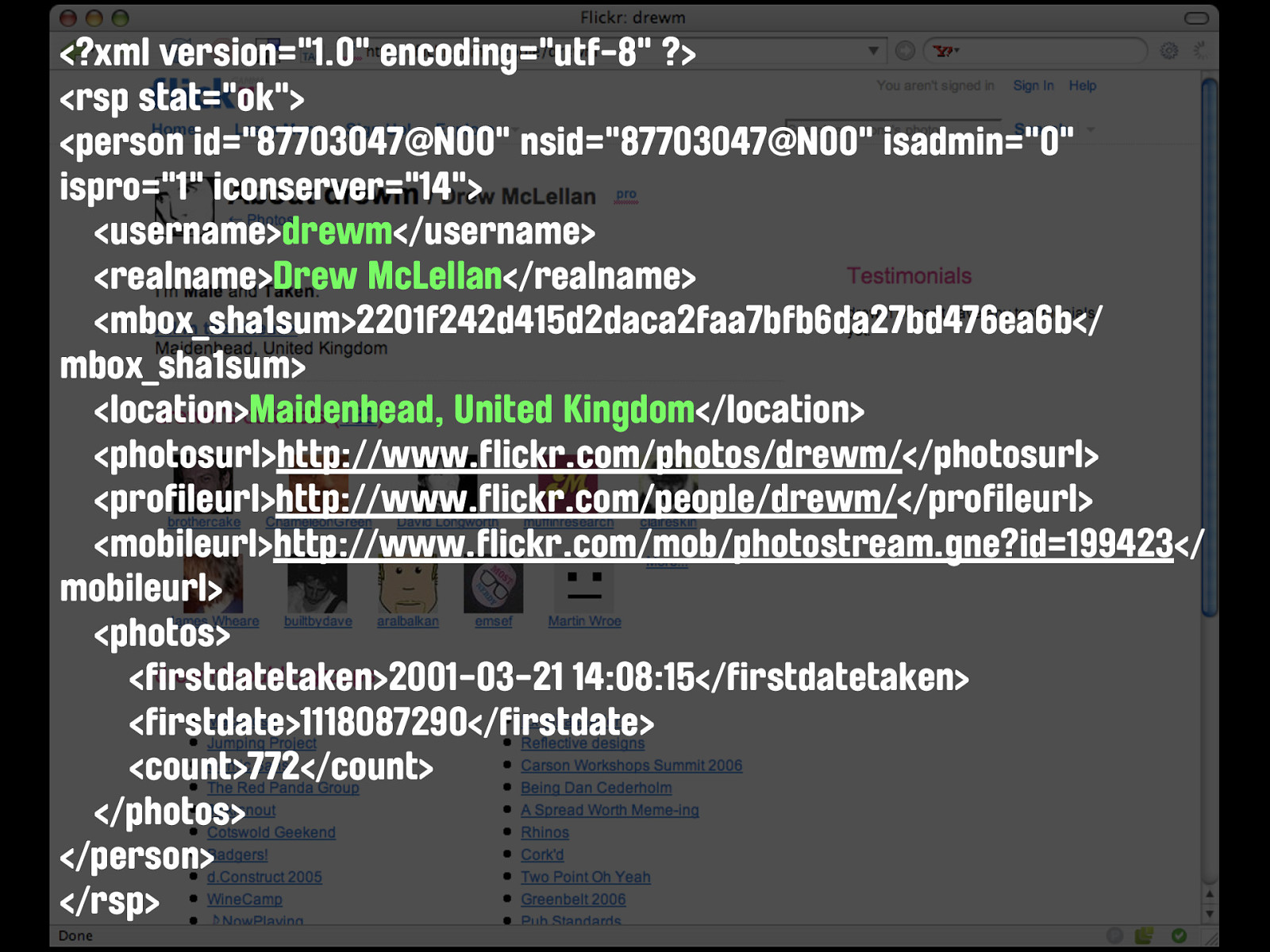

flickr.people.getInfo The equivalent request from the Flickr API is flickr.people.getInfo.

http://api.flickr.com/ services/rest/ ?api_key=<API Key> &method= flickr.people.getInfo &user_id=87703047@N00 Except you'll notice that the user_id I've provider here isn't my username. That's because behind every friendly user identifier in the application, Flickr has a nasty numerical identifier which is guaranteed to be unique.

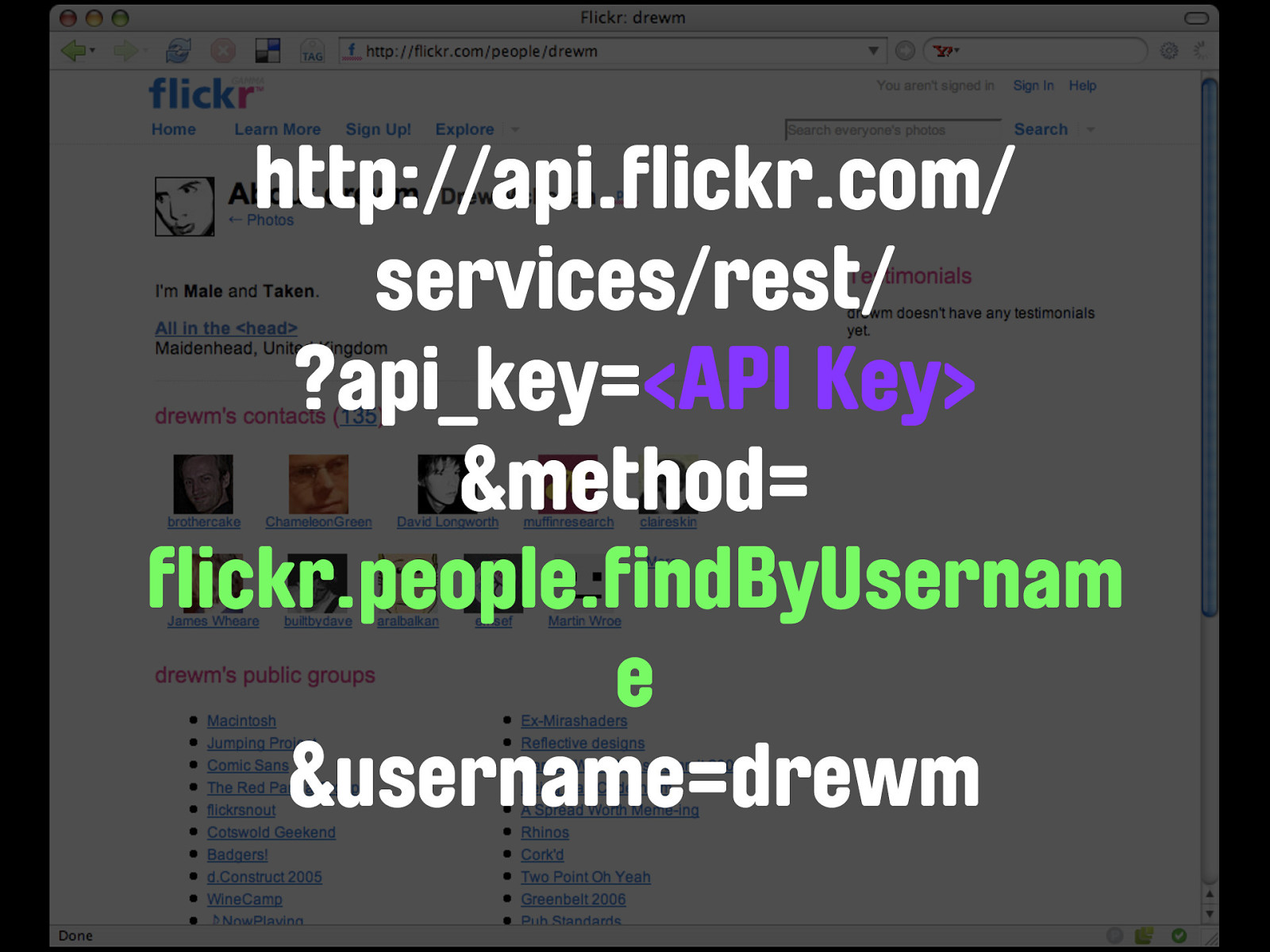

flickr.people.findByUsername Therefore, before I can make a call to flickr.people.getInfo, I need to find the user_id by the way of a call to flickr.people.findByUsername.

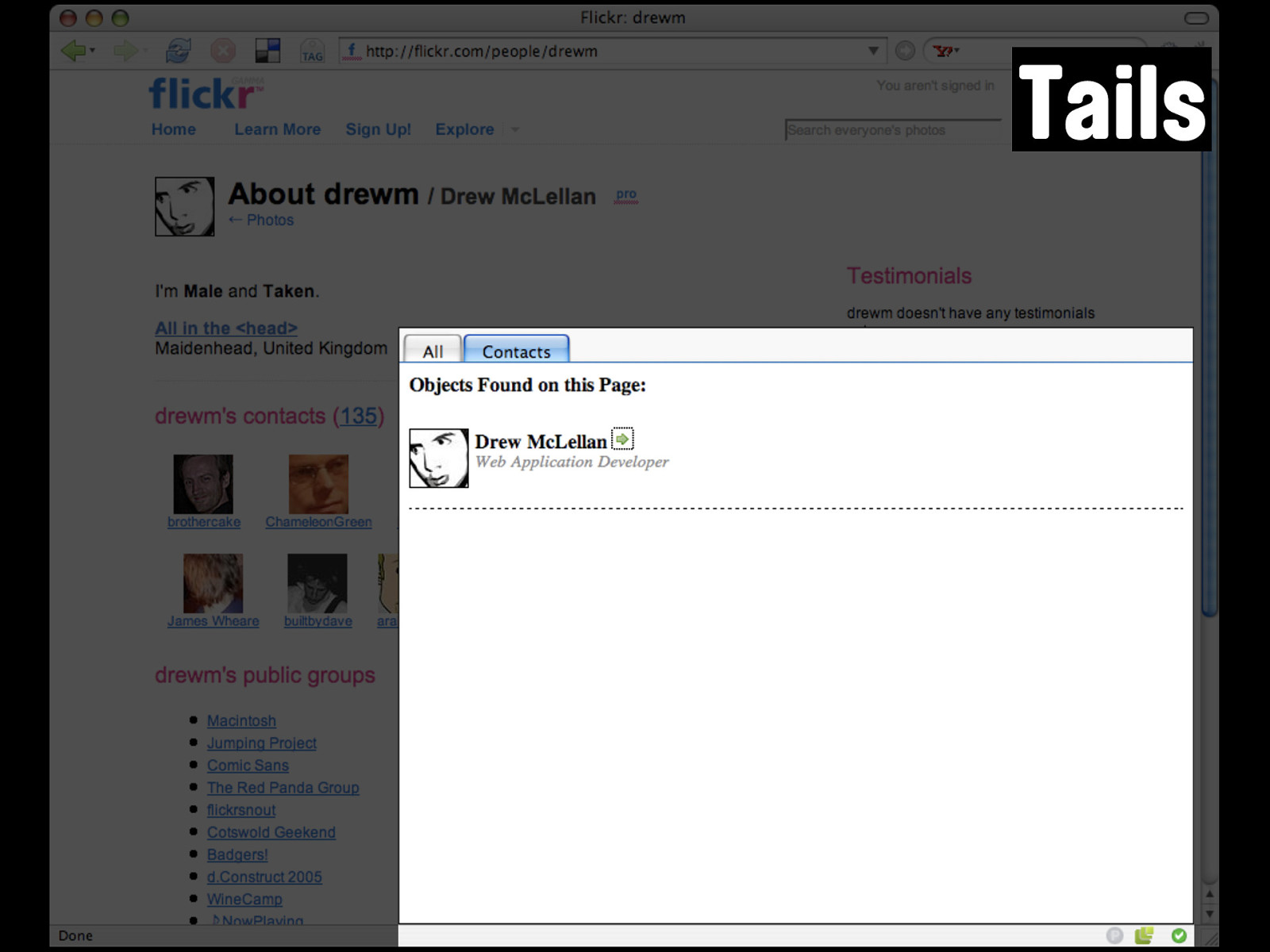

http://api.flickr.com/ services/rest/ ?api_key=<API Key> &method= flickr.people.findByUsernam e &username=drewm If we run our parsers over this, just as with the Upcoming.org events page...

Tails we can see Tails finds the data

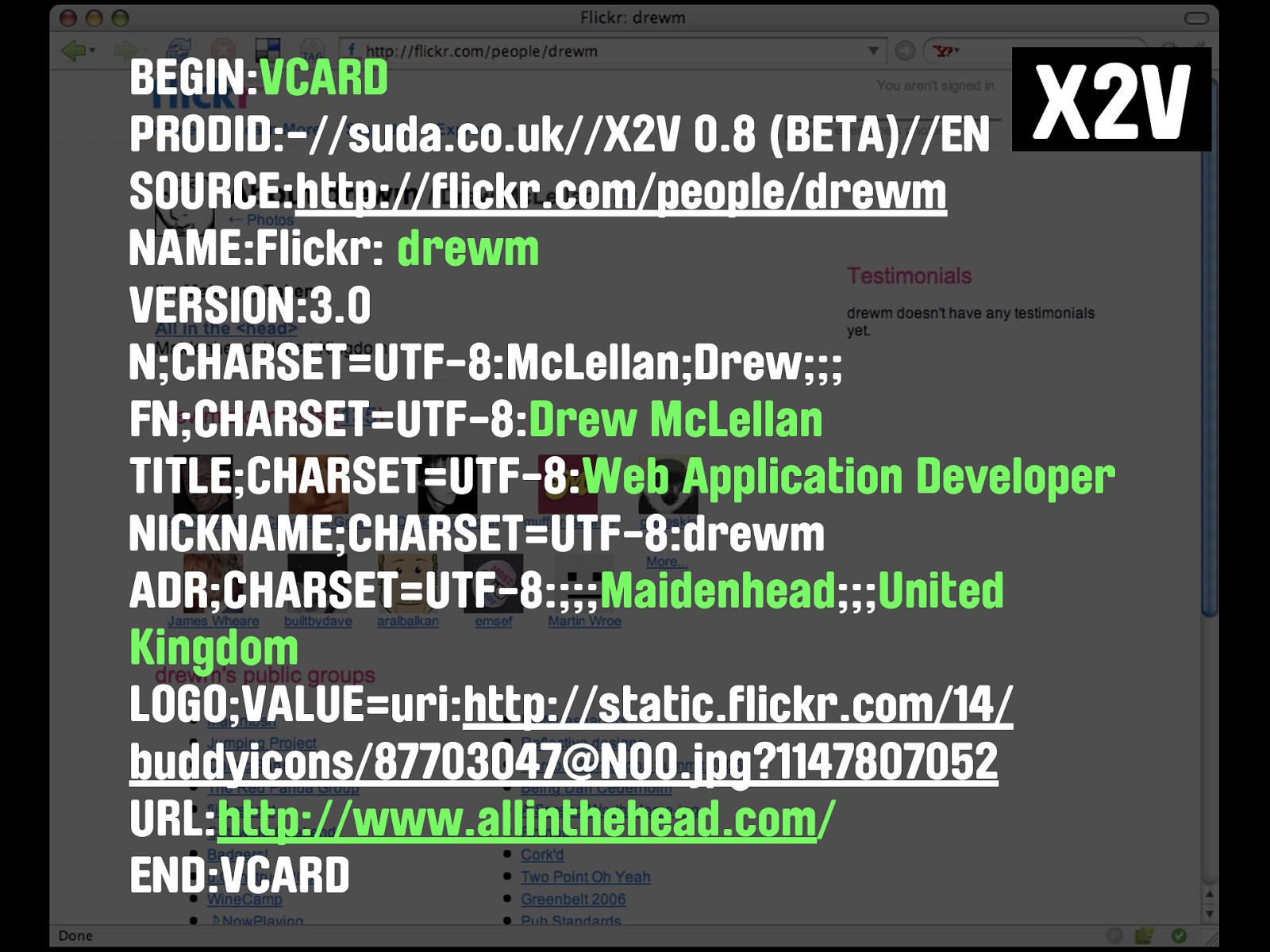

X2V BEGIN:VCARD PRODID:-//suda.co.uk//X2V 0.8 (BETA)//EN SOURCE:http://flickr.com/people/drewm NAME:Flickr: drewm VERSION:3.0 N;CHARSET=UTF-8:McLellan;Drew;;; FN;CHARSET=UTF-8:Drew McLellan TITLE;CHARSET=UTF-8:Web Application Developer NICKNAME;CHARSET=UTF-8:drewm ADR;CHARSET=UTF-8:;;;Maidenhead;;;United Kingdom LOGO;VALUE=uri:http://static.flickr.com/14/ buddyicons/87703047@N00.jpg?1147807052 URL:http://www.allinthehead.com/ END:VCARD X2V finds the data...

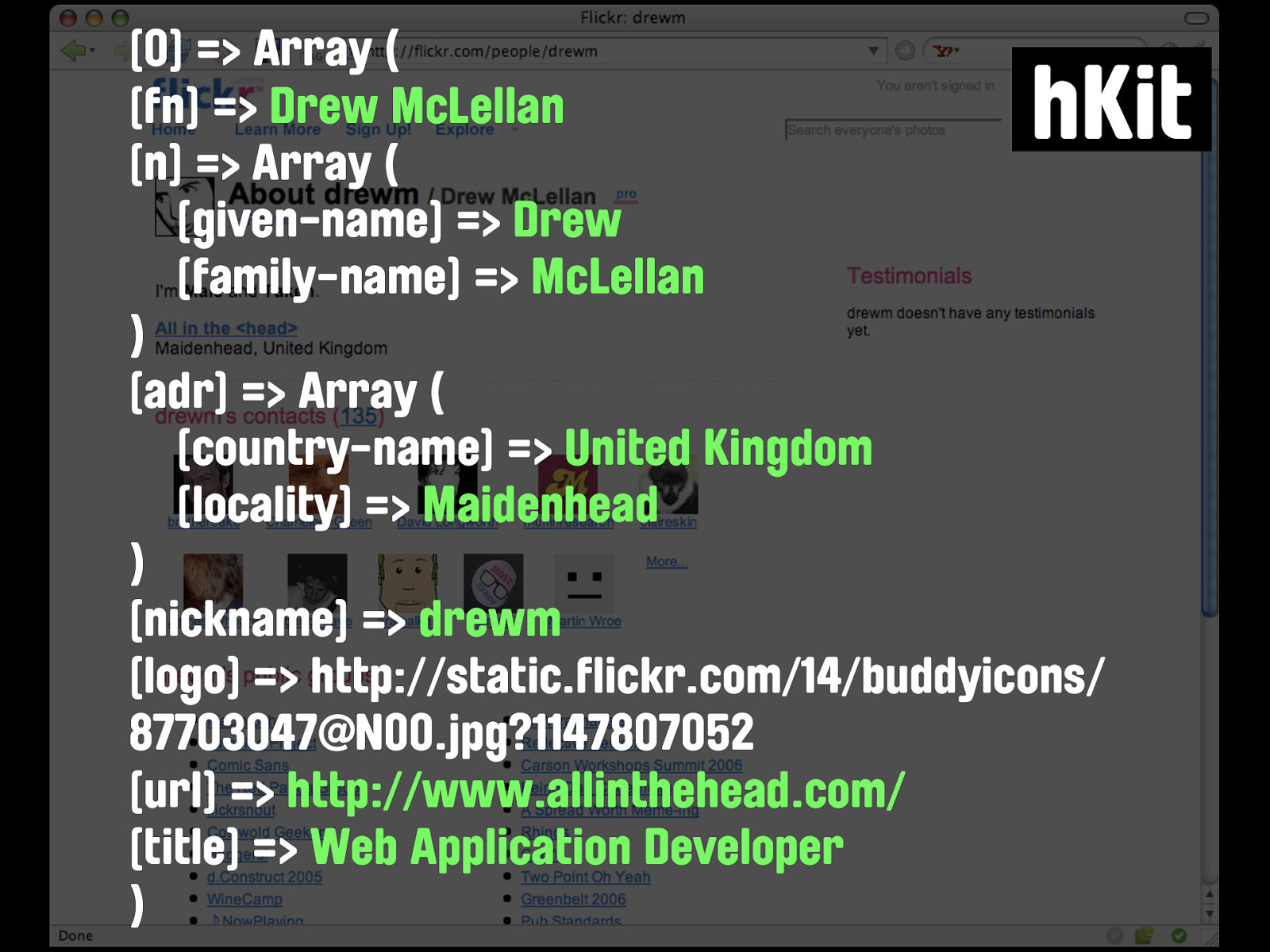

[0] => Array ( [fn] => Drew McLellan [n] => Array ( [given-name] => Drew [family-name] => McLellan ) [adr] => Array ( [country-name] => United Kingdom [locality] => Maidenhead ) [nickname] => drewm [logo] => http://static.flickr.com/14/buddyicons/ 87703047@N00.jpg?1147807052 [url] => http://www.allinthehead.com/ [title] => Web Application Developer ) hKit and hKit finds it too.

flickr.people.getInfo Every user has a profile page, so this renders flickr.people.getInfo redundant.

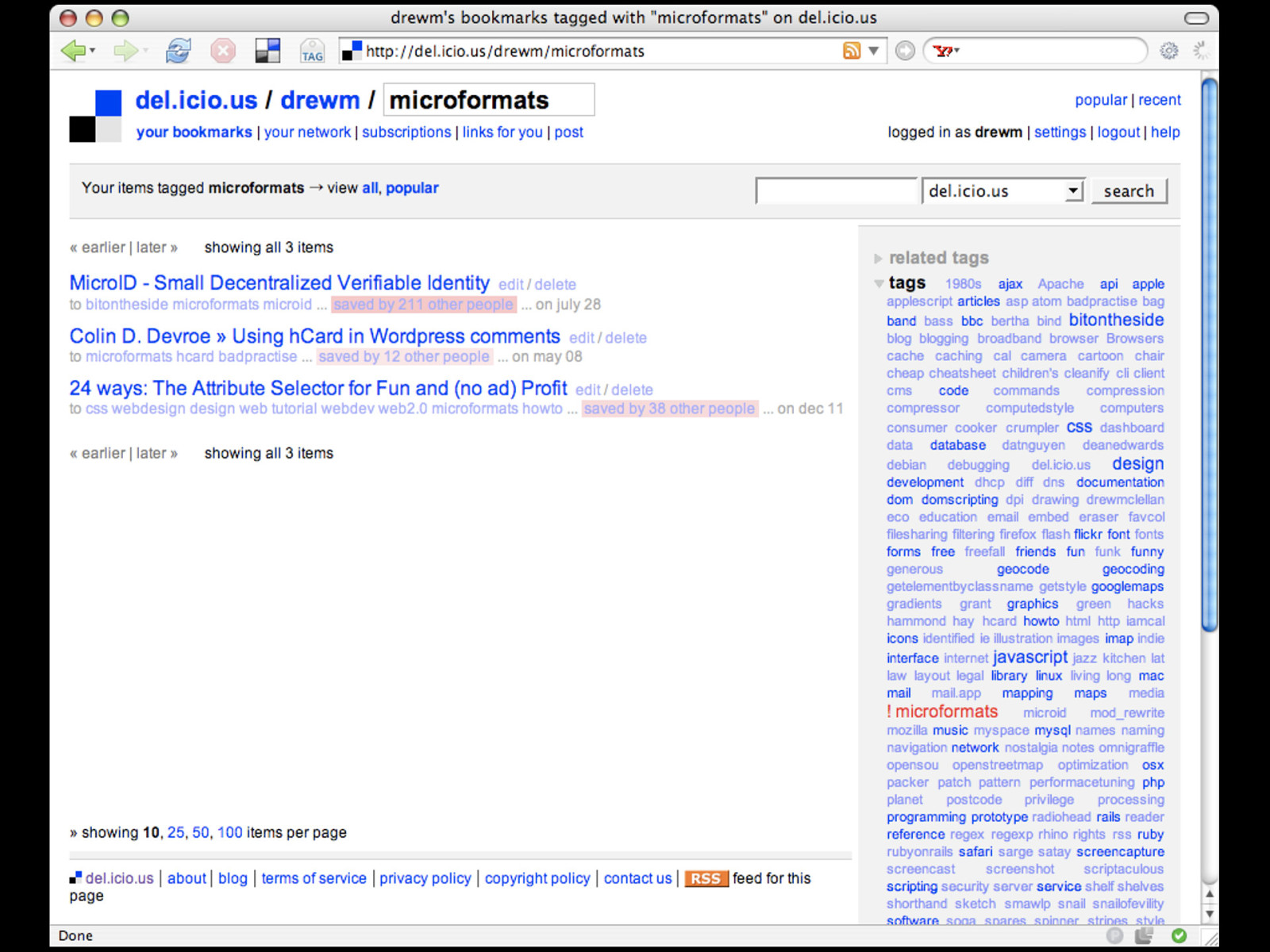

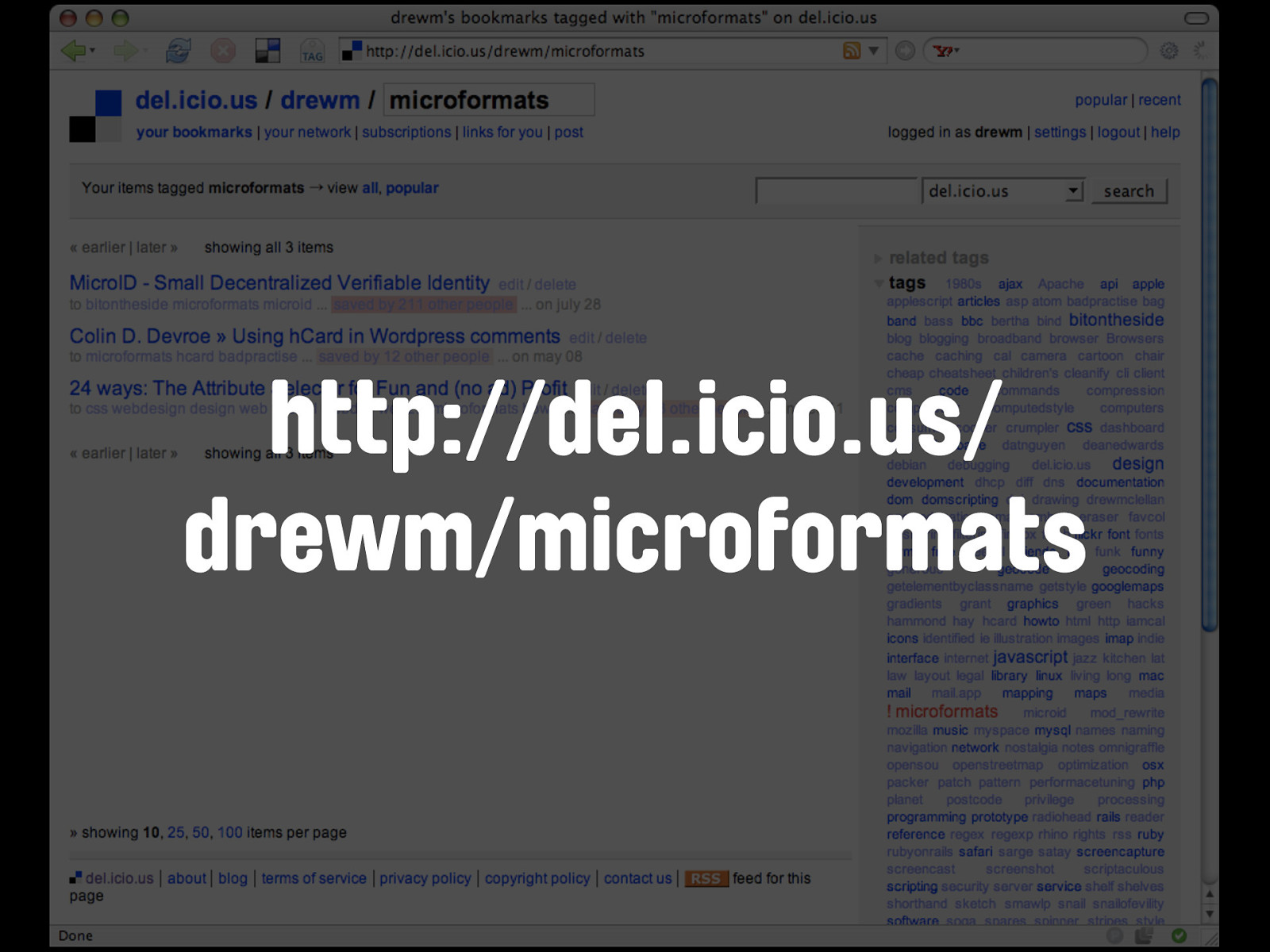

So since we're working our way through Yahoo's family of Web 2.0 poster children, let's do the same with del.icio.us. The URI of my page listing bookmarks for the tag 'microformats' takes a slightly different, simpler form this time.

http://del.icio.us/ drewm/microformats We have the service name - del.icio.us - as the service deals with bookmarks way more than anything else, that's the default item for retrieval, so we go right in with my username - drewm - and then the identifier for the data we want - which in this case is the tag 'microformats'.

:’( Looking for the output in Tails - is disappointing, as del.icio.us doesn't have support for microformats yet. :-(

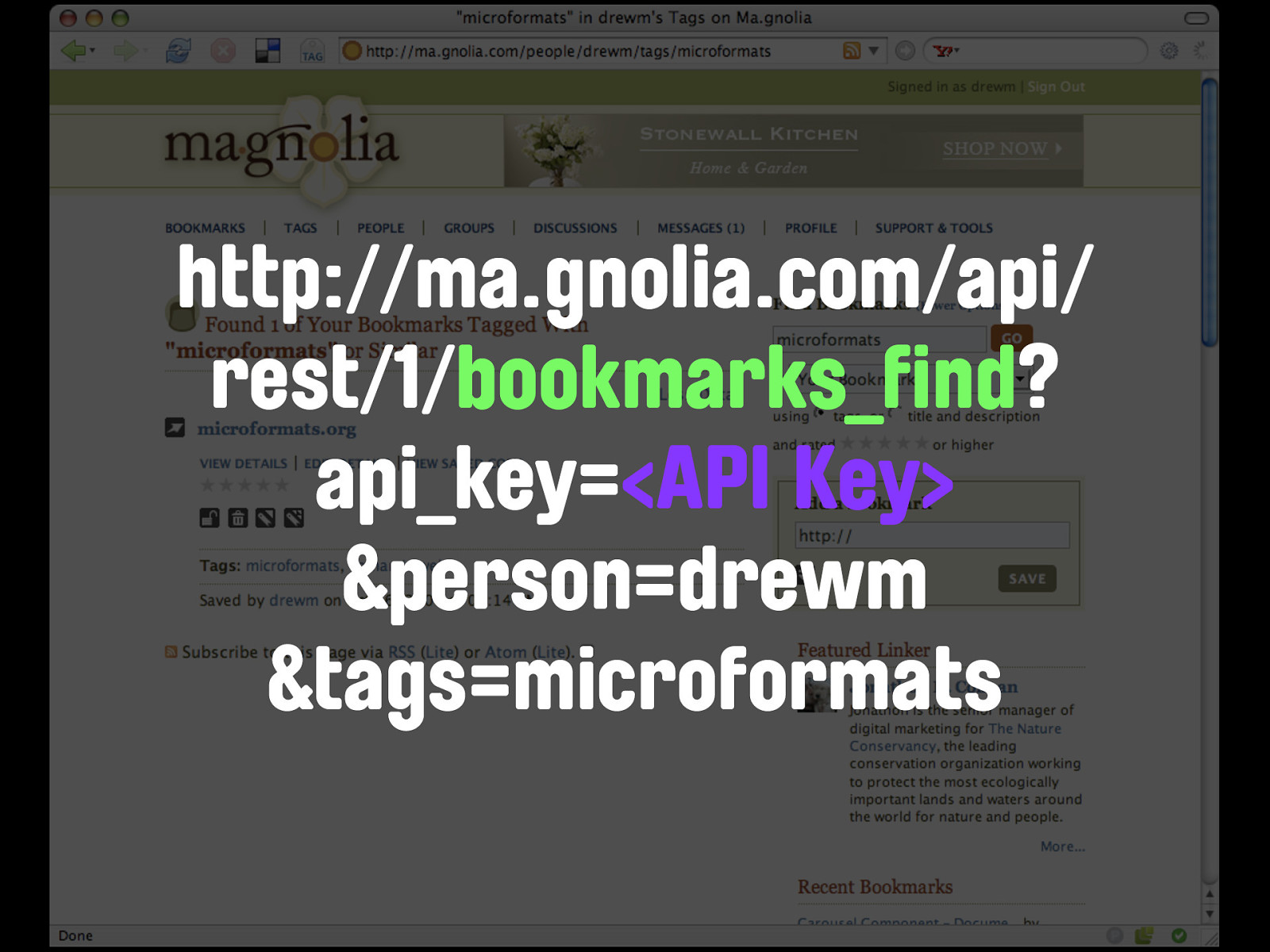

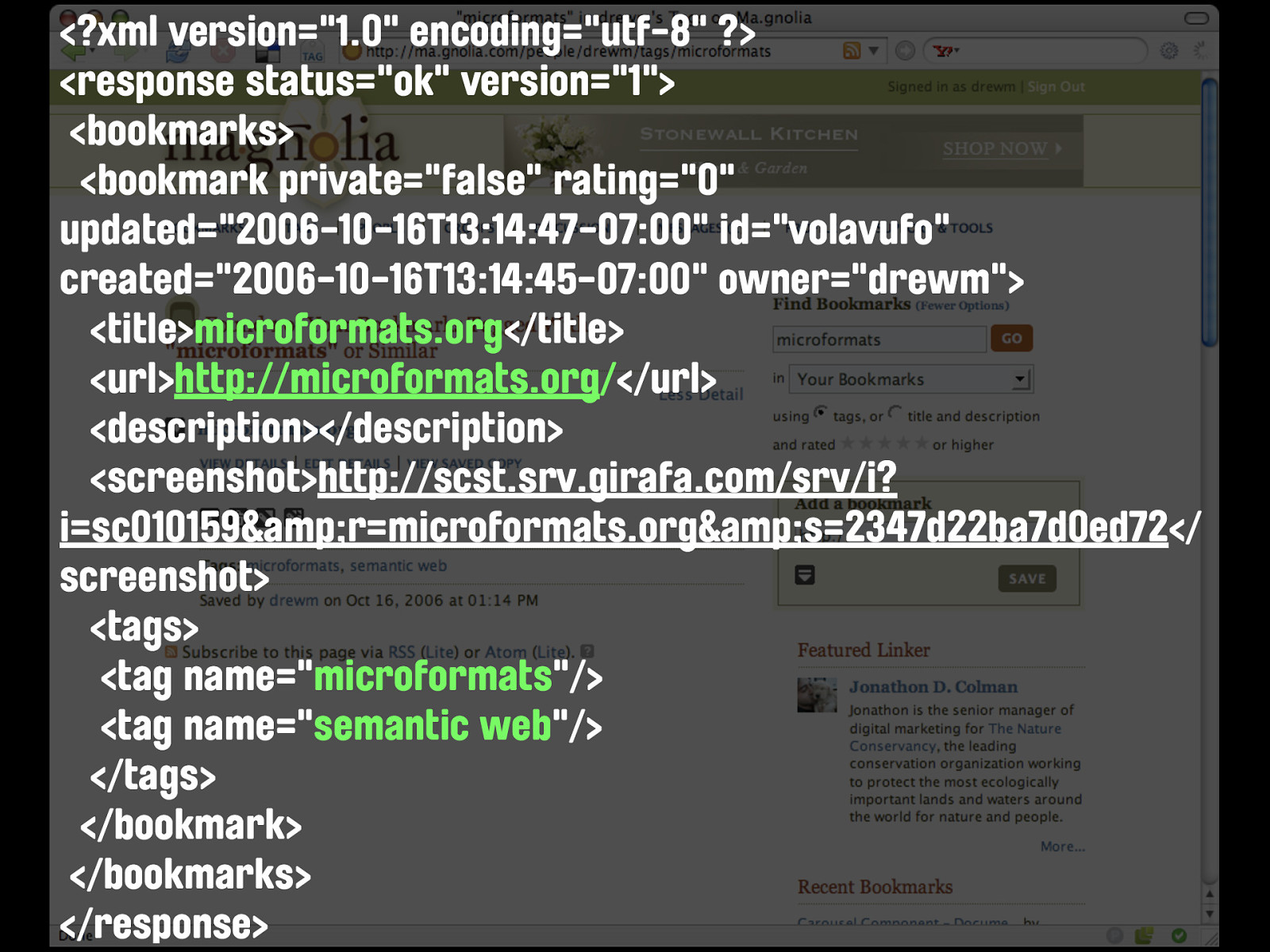

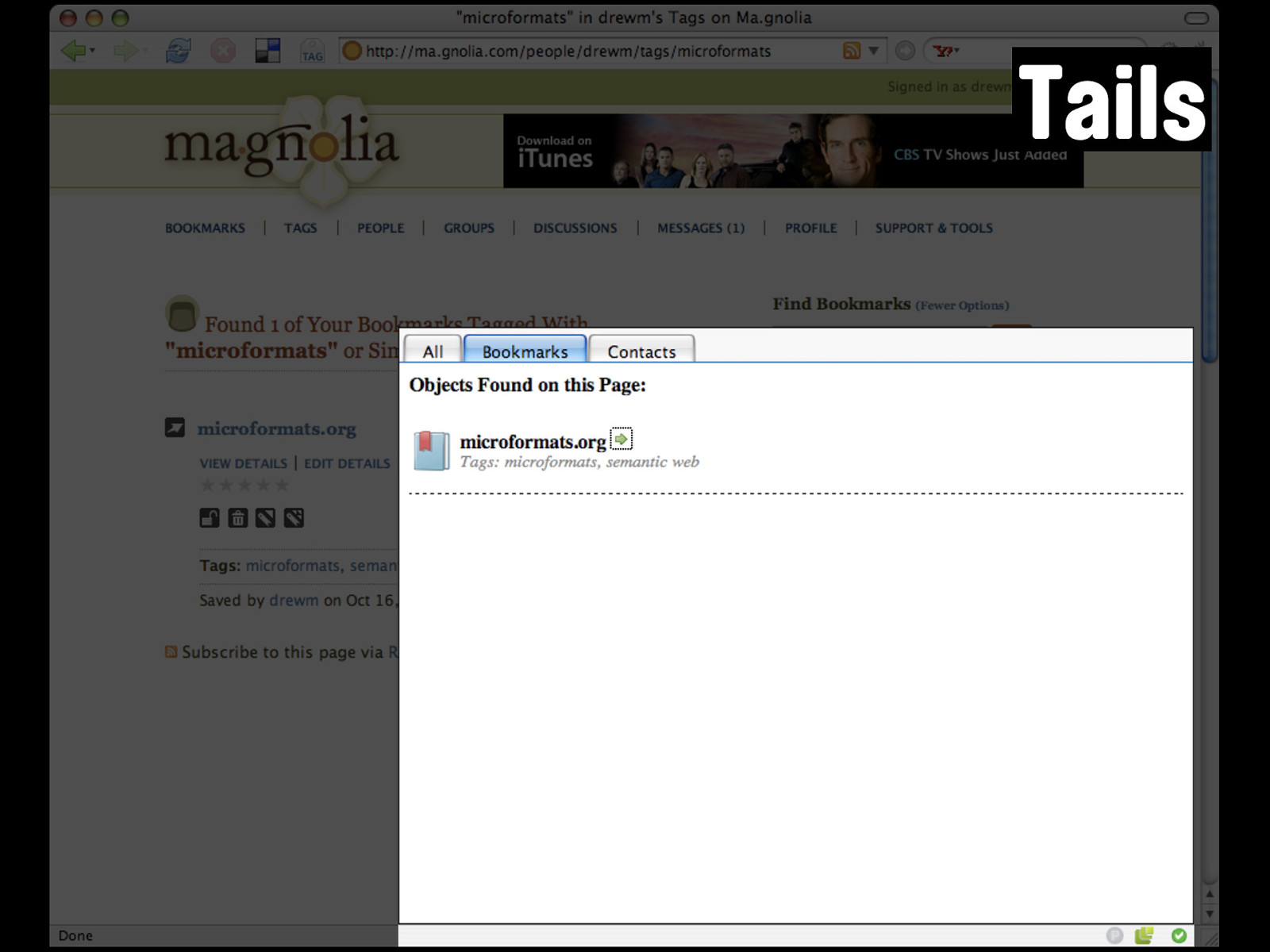

The good news is that Ma.gnolia does! So here's the same query from there.

http://ma.gnolia.com/ people/drewm/tags/ microformats

bookmarks_find The equivalent method from the Ma.gnolia API is bookmarks_find

http://ma.gnolia.com/api/ rest/1/bookmarks_find? api_key=<API Key> &person=drewm &tags=microformats there’s the request

Tails Here it is in Tails, using the xFolk microformat. hKit has preliminary support for this too.

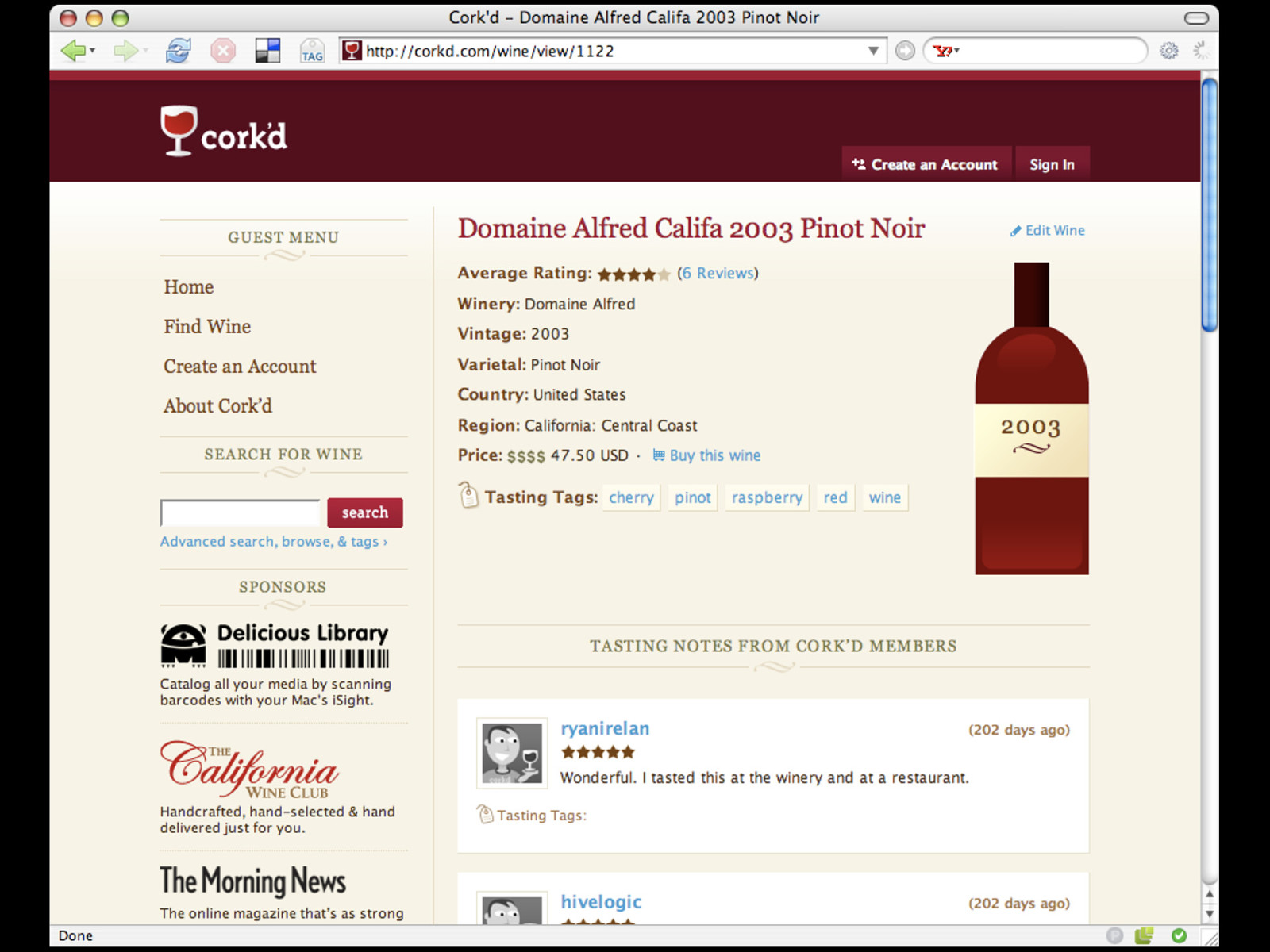

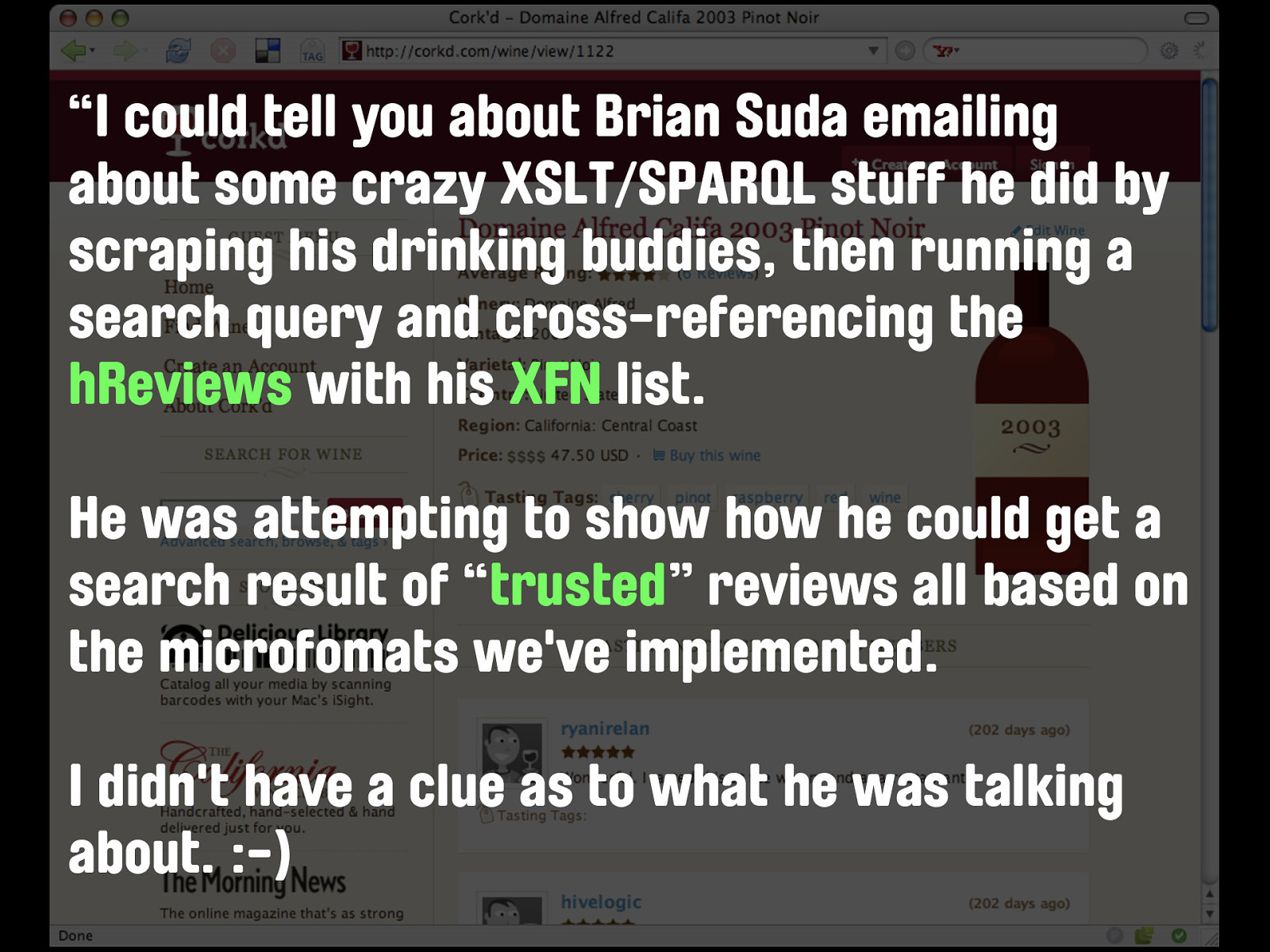

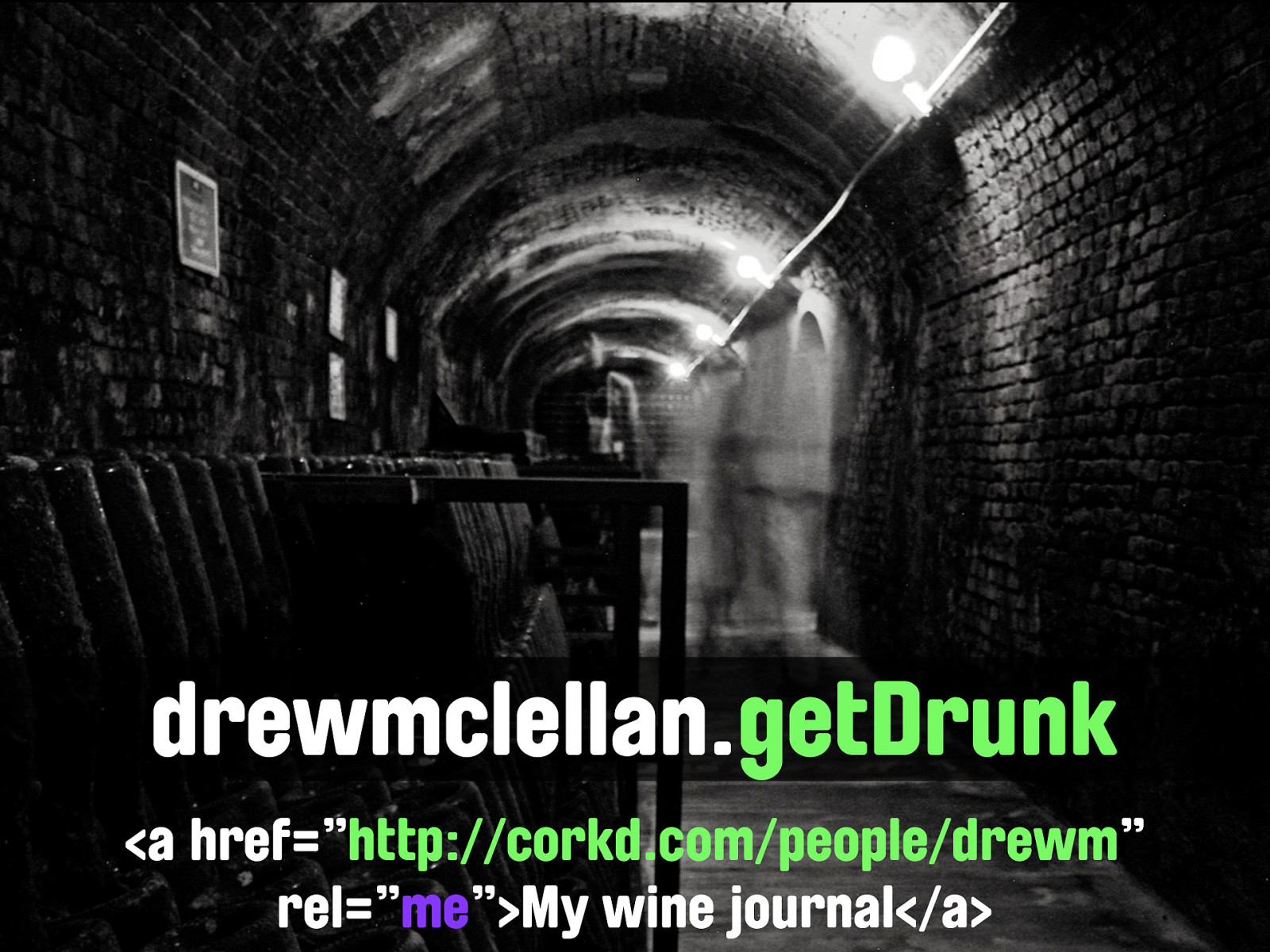

Similarly, say I wanted to get reviews for a particular wine from corkd.com.

http://corkd.com/wine/ view/1122 Again we have the service name - corkd.com - the object we're looking for - wine - this time a sort of 'mode' indicator - view - and then the unique identifier for the wine. A human visitor gets the wine details and the reviews on that page. The equivalent API method for the corkd API is ...

:’( ... well, corkd has no separate API.

Fortunately, corkd is rich in microformats, including hReview. Running a parser over the wine detail page gives us all the data we need. Even without a formal API. Hah!

Tails That’s a whole list of reviews and ratings directly accessible from the page with no separate API. I asked Dan Cederholm - the front-end guy behind Cork’d about this choice - and he said...

“I could tell you about Brian Suda emailing about some crazy XSLT/SPARQL stuff he did by scraping his drinking buddies, then running a search query and cross-referencing the hReviews with his XFN list. He was attempting to show how he could get a search result of “trusted” reviews all based on the microfomats we've implemented. I didn't have a clue as to what he was talking about. :-)

But that's the beauty of it! Something I'm calling “oblivious development”. I've always looked at microformats as “planting seeds” that later grow into things you never even thought of. microformats are so easy to sprinkle in, that as designer I can plant the stuff that later someone like Brian Suda can do insane things with. I love that. I don't understand the stuff that Brian was doing - but I don't have to.” Dan Cederholm, Cork’d

This is a key difference between publishing an API and letting your data just speak for itself. When designing an API, you have to consider what data users might need, and to an extent how they’re going to use it. Those decisions have already been made for your website as part of your information architecture, and that data is already being published. The only effort involved is in more careful choice of markup when building the page.

read/write Of course, there’s more to APIs than just retrieving data. Whilst reads are the VAST majority of the traffic to most common APIs, a lot of the concept, at least, is about writing data back too. Fortunately, that’s the easy part of the problem too. Sending data to a service is already in a structured format, as is already in a format specified by the provider. An HTTP POST is already works in this way by its nature. If we were to extend the idea, we could specify a common format for POSTing events or contact details, and indeed there’s already work happening on that within the microformats community.

Cook’d? So is what I’m suggesting ready for the prime time? Can you forget about building an API and rely on good semantics to get you through? For reads, yes, absolutely. Cork’d are doing it today. If you need to have a fully read/write environment, possibly not quite yet. It’s yes but no.

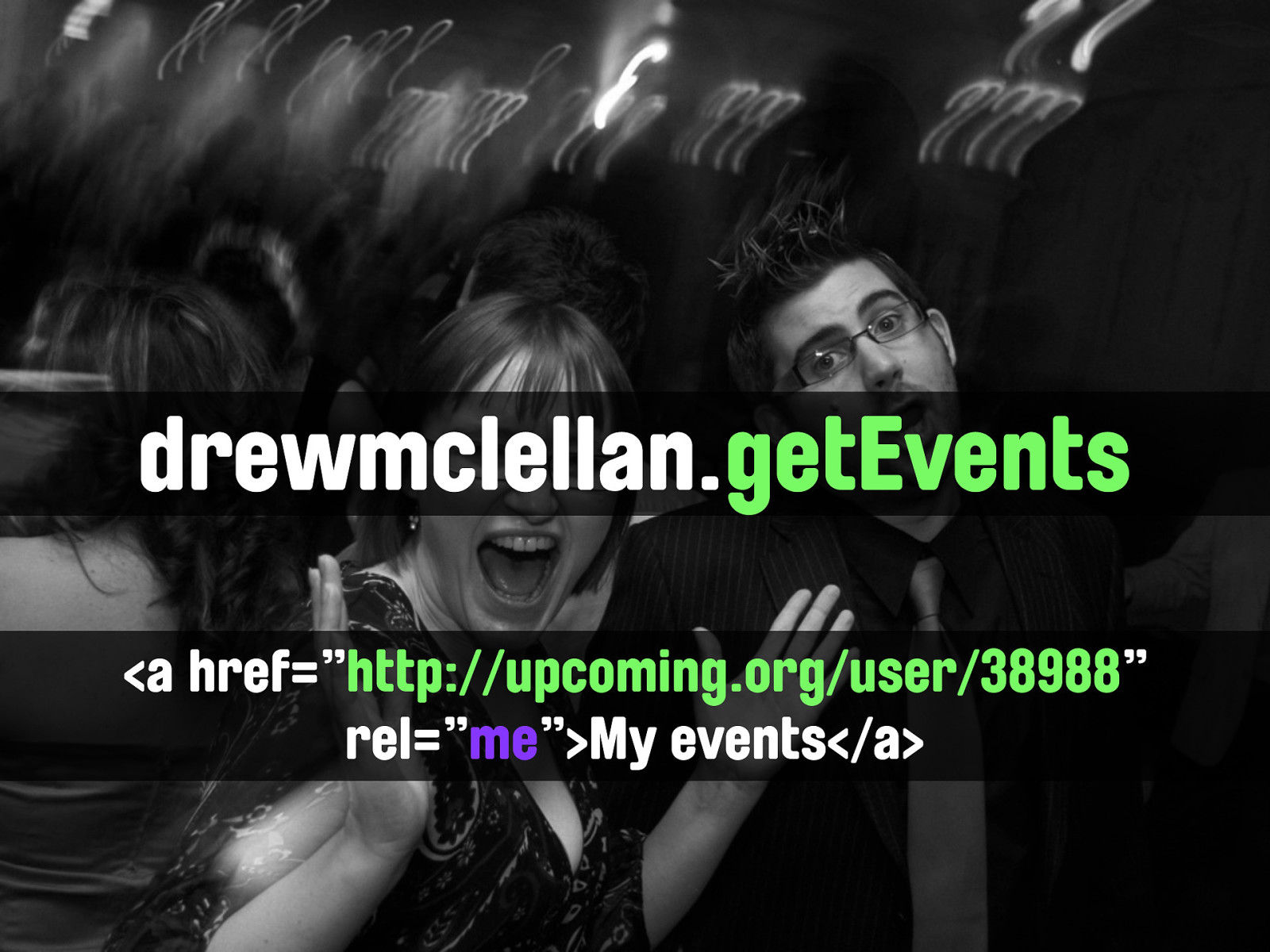

drewmclellan.getInfo The real power is, however, perhaps in the places where we wouldn’t normally consider building an API. What if I wanted to make a request to drewmclellan.getInfo. Or drewmclellan.getEvents. There’s no such API, and I’d probably have to be very very sad to build one. (Hands up if you’ve done this!)

http://allinthehead.com/about In fact, this already exists. Because I already publish things about myself on my own site, by using microformats, there’s an API for me.

drewmclellan.getPhotos <a href=”http://flickr.com/photos/drewm” rel=”me”>My photos</a>

drewmclellan.getEvents <a href=”http://upcoming.org/user/38988” rel=”me”>My events</a>

drewmclellan.getDrunk <a href=”http://corkd.com/people/drewm” rel=”me”>My wine journal</a>

So what? So what does this really mean to me as a user? What does this enable that doesn’t exist at the moment? Well, it’s not just giving us a free API into our data - it’s also giving us a COMMON API into that data. Because it’s just HTML and lives at the same URI it means that it’s possible to query that API without really knowing anything special about it.

Let’s take a brief diversion and talk about OpenID for a moment. OpenID is an open, decentralized, free framework for digital identity. It starts with the concept that anyone can identify themselves on the Internet the same way websites do-with a URI.

http://drewmclellan.net/ This is extremely useful because it enables us to replace the username and password pair with a single internet address that can vouch for who we are. Out on the web this might be anything from an AOL or LiveJournal account through to an identity server I run myself. Inside an institution such as a University, this could be a central, internal identity server that is able to - through whatever mechanism it likes - vouch for the identity of any given student.

http://openid.net/ By identifying myself with a URI I’m giving a location on the web that knows more about me. So from a single URI we can both establish an identity for a user and find out as much information as their willing to share. On the public web, or in a closed environment such as an enterprise or institution, the combination of these technologies provides an excellent, loosely coupled system for sharing a user database amongst a disparate range of applications and systems.

So what? And just like OpenID enables authentication interoperability through a common protocol, microformats offer data exchange that can be taken for granted. Back to our question - so what does this really mean to me as a user?

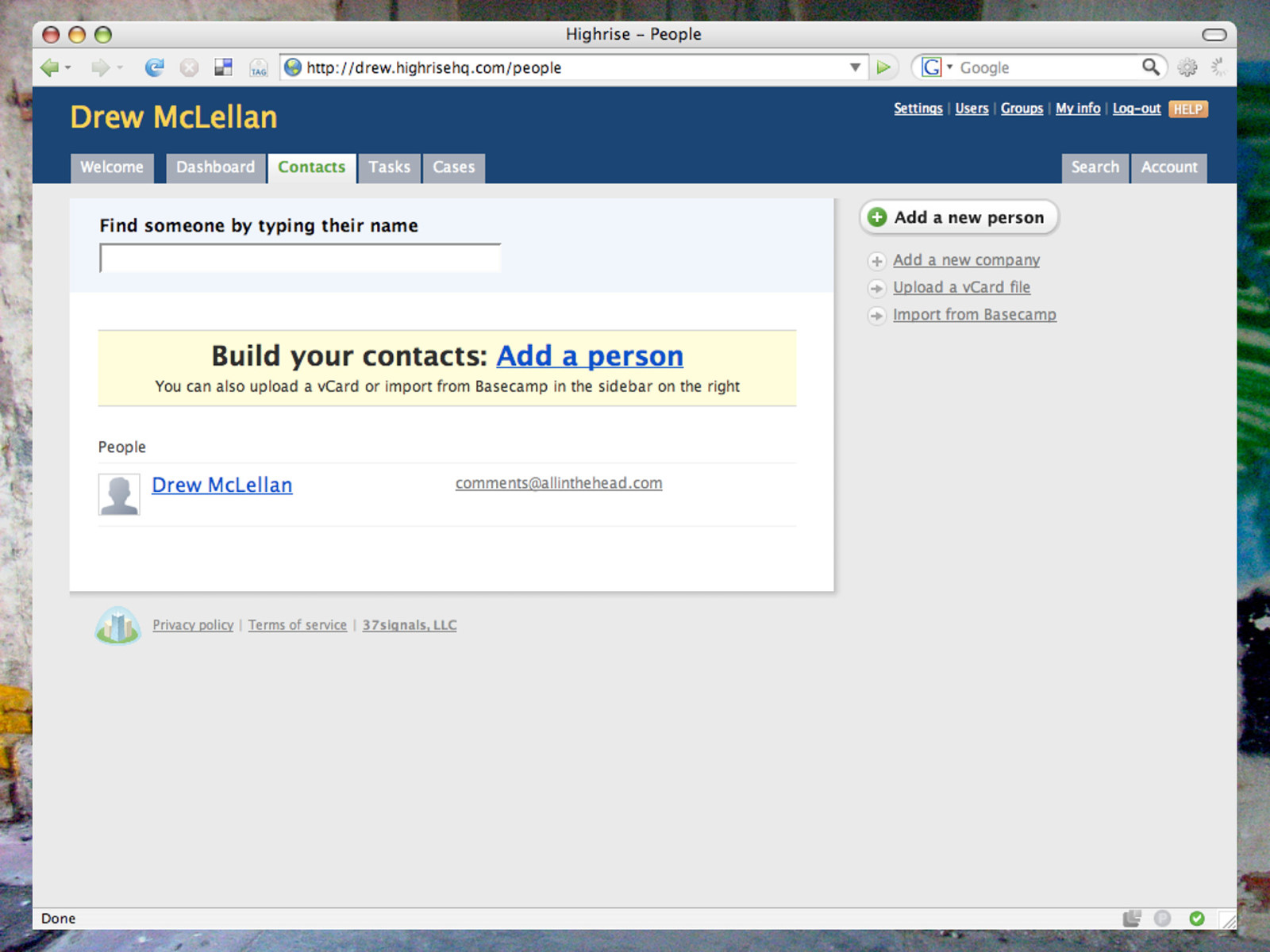

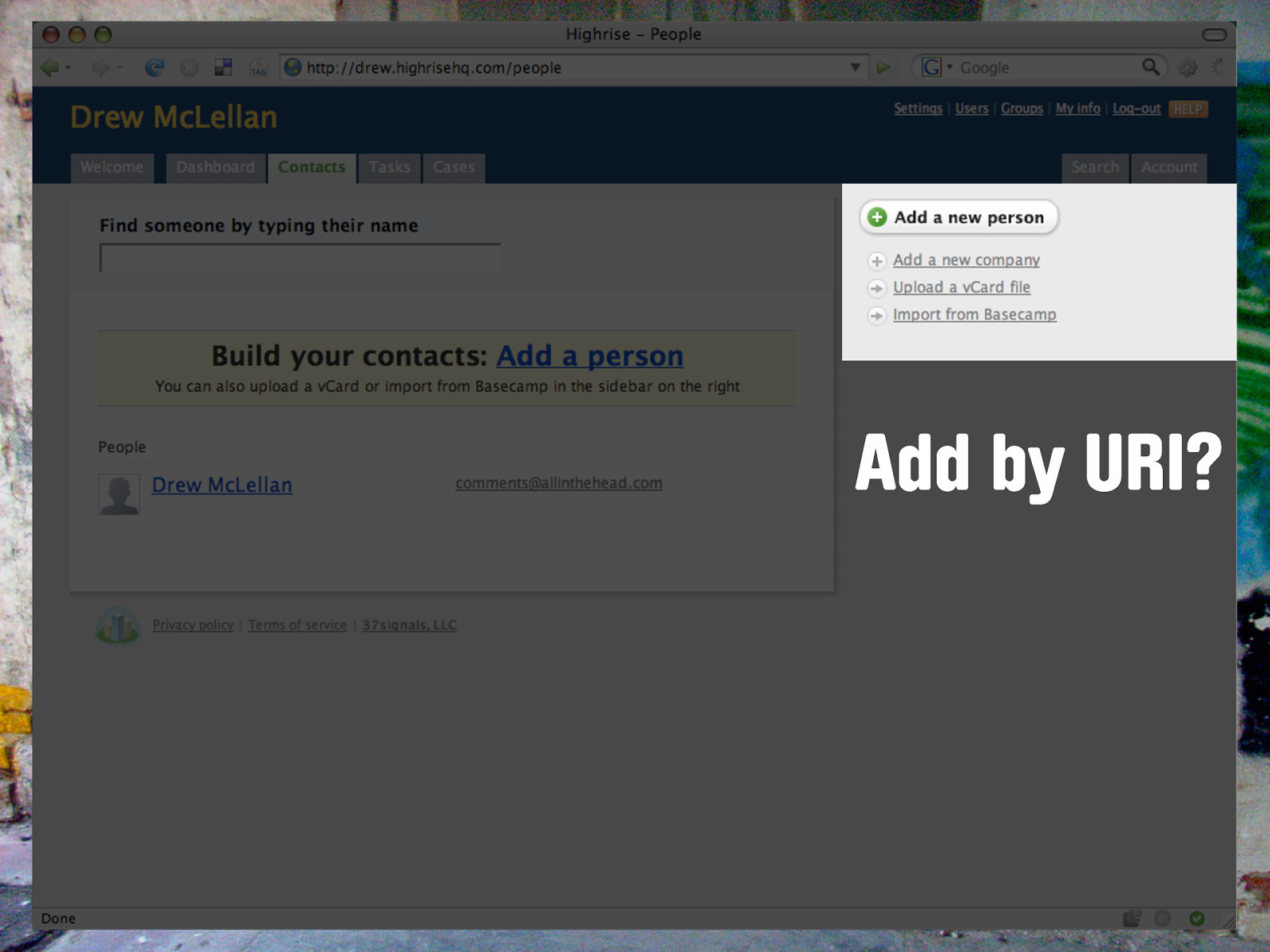

This is the My Contacts page on my HighriseHQ account. Highrise is a web based CRM tool from the folks at 37signals. In the top right there we can add a new person through their form, upload a VCARD file from a desktop address book or import contacts from another product from the same company, Basecamp.

Add by URI? But let’s say I want to add my friend Jeremy to this account. I don’t know his address off hand, and I know he recently moved offices and moved house a few months back so the address book on my computer is probably out of date. I do know that both his personal site and business site are nicely marked up with hCard, and I know those URIs So why can’t I just specify a URI and have a person added that way? Thanks to OpenID we can identify ourselves by URI - so why not other people too? With microformats this becomes possible - 37signals could implement that today if they chose to.

Can I add enough semantic information to the pages I already publish so that they could replace the function of a dedicated API?

Can I add enough semantic information to the pages I already publish so that I get an API thrown in for free?

Hell yeah. If you're a data publisher, all you need to do is put into practise some of the basic microformats we’ve discussed a little today. Marking up your content with microformats is no only a good place to start, but the BEST place to start.

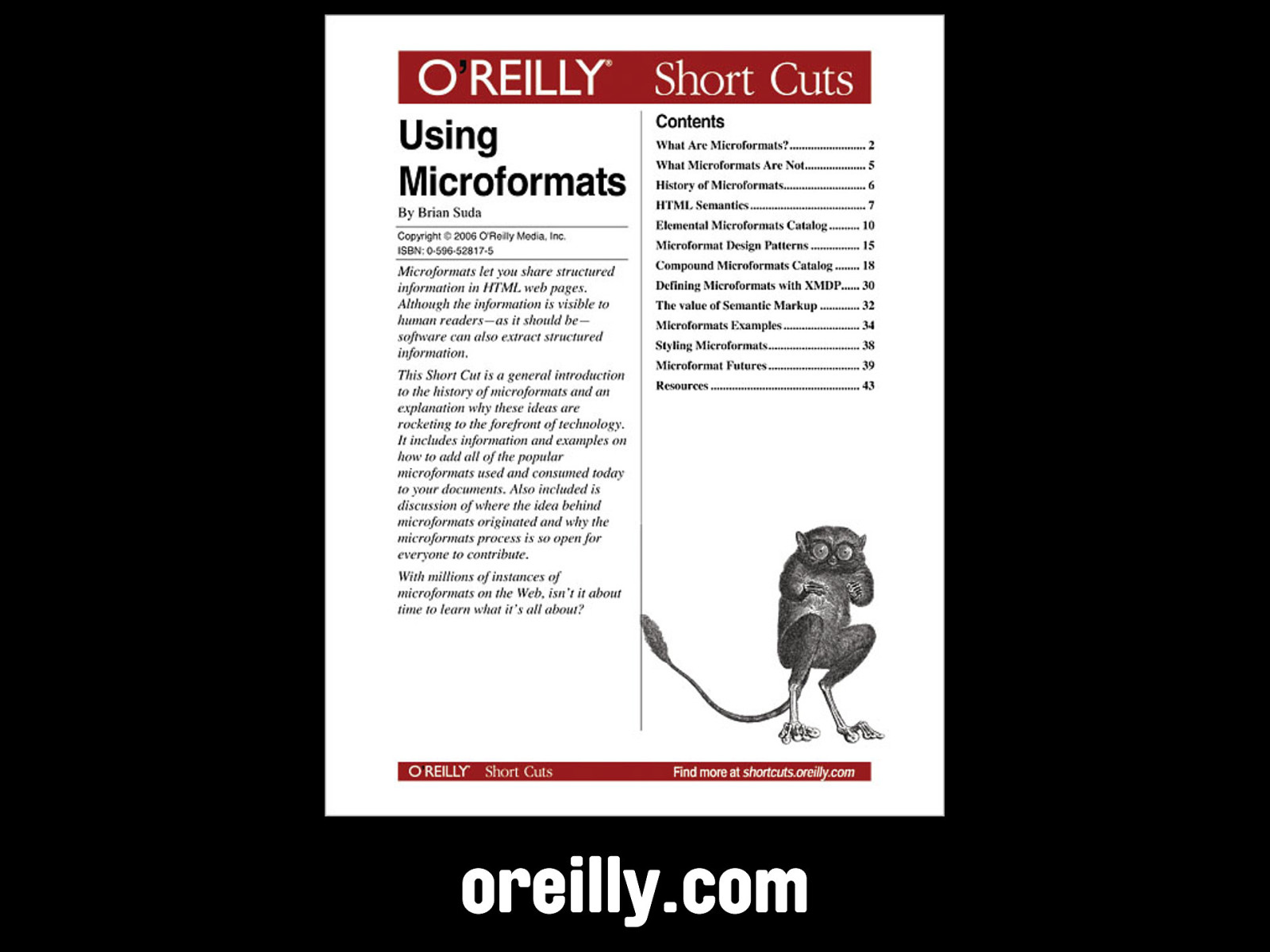

oreilly.com O’Reilly have a short ebook available, written by Brian Suda. It’s only a few dollars, and is available for download from oreilly.com Also new book called ‘Microformats: empowering your markup for Web 2.0” from Friends of Ed by John Allsopp

Can your website be your API?

Fo shizzle.

Thanks! http://allinthehead.com/presentations/2006/mf-api

Credits the following Creative Commons licensed images were used in this presentation

http://flickr.com/photos/adactio/169052553/ http://flickr.com/photos/tgraham/253500273/ http://flickr.com/photos/gabrielhl/76450732/ http://flickr.com/photos/mpdehaan/21006425/ http://flickr.com/photos/splorp/64027565/ http://flickr.com/photos/vampire_bear/15910260/ http://flickr.com/photos/agos/240924445/ http://flickr.com/photos/brook/65076098/ http://flickr.com/photos/shveckle/204895620/ http://flickr.com/photos/poagao/23805079/ http://flickr.com/photos/z1784/69981580/ http://flickr.com/photos/johnnyhuh/812894/ http://flickr.com/photos/gperez/4393118/ http://flickr.com/photos/isphoto/54113178/ http://flickr.com/photos/flashmaggie/6271604/ http://flickr.com/photos/rachelandrew/169006965/ http://flickr.com/photos/scatti_frullati/156505041/ http://flickr.com/photos/thedepartment/137413905/ http://flickr.com/photos/camera_rwanda/265802151/ http://flickr.com/photos/esther17/171786999/ http://flickr.com/photos/ianlloyd/264755178/

http://flickr.com/photos/publicenergy/74773382/ http://flickr.com/photos/whatwhat/91374586/ http://flickr.com/photos/donsolo/314184695/ http://flickr.com/photos/badjonni/386624296/ http://flickr.com/photos/gehmflor/375334958/ http://flickr.com/photos/vidiot/69075298/ http://flickr.com/photos/bitzi/265052661/ http://flickr.com/photos/nolifebeforecoffee/124659356/ http://flickr.com/photos/stewdean/30705594/ http://flickr.com/photos/niznoz/111012362/ http://flickr.com/photos/docman/43269391/ http://flickr.com/photos/larimdame/4967439/ http://flickr.com/photos/pbo31/428964423/