Centring human rights and trauma in design. Working with traumatic subject matter as a designer. Access slides here: bit.ly/UCD-2022-EF-Trauma-and-Design

A presentation at UCD Gathering in June 2022 in by Eriol Fox

Centring human rights and trauma in design. Working with traumatic subject matter as a designer. Access slides here: bit.ly/UCD-2022-EF-Trauma-and-Design

I’ll take some time to cover content warnings. I ask that if you have personal and traumatic experiences of these topic that you consider what you might need to help keep you safe as you listen and make the precautions you might need during this intro section of the talk. These topics can be difficult to listen to even without intimate experience and they can affect us all in different ways. I primarily am interested in your safety, comfort and well being as we talk about difficult topics and our relationship to them as technologists.

Our structure 01 | Human Rights Centered design 02 | Stories about designing technology and Human Rights. 03 | Journey mapping exercise 04 | Wrap up

Simply Secure (simplysecure.org) is a design nonpro t based in Berlin and NYC, founded in 2014. We design and support responsible technology that enables human dignity. We offer design and strategy support for: • Open technology tools • Privacy, security, decentralisation, transparency, human rights tools • Nonpro ts working in and around technology @UCDGathering #ucdgathering fi fi @EriolDoesDesign

Hi, I’m Eriol. (Ehh-roll). They/Them pronouns. 12 years in digital product design and UX. 9 years in humanitarian / third sector. 5 years in (FL)OSS technology. PhD student researching Humanitarian OSS and Design. I’m a human rights centred designer. @EriolDoesDesign @UCDGathering #ucdgathering

So, I’m a human rights centred designer, what does that mean?

You may have heard of the term human centred designer, where the designers of tools, software and experiences aim to centre the ‘human’ in their work, this doesn’t mean that the technology goals or business goals are ignored, but rather centres the humans, the people, in what they use and need ensures that the right choices are being made for them as the ‘primary’ reason that that technology is created and useful.

Because after all, the people that use these technologies, these tools we make are the forward momentum defining what is created, and that creation must be useful and valid for them.

Human rights centred design differs in a way where we not only consider the needs of people that will use and experience what we create, but their known and unknown human rights within these interactions with technology.

A reasonably quick example of this could be around privacy. Say you’ve created a tool that has a feature where people can have location enabled and stored within the tool. Most people, we assume know their own needs around location well enough and are competent enough with tools generally that if we make options for security of that location data accessible that the people that use it will choose the privacy configuration that work for them.

This example already makes a lot of assumptions, primarily that the people know what the risks to their safety are more widely. In the same example, consider someone who’s identity is criminalised (we could look to LGBT+ communities here) and we could begin to think about what they might need, to protect their rights and safety that are not part of our simple assumed story.

I began to think more in this way after lots of community work and working in human rights.

Before I started to join my work in design and human rights, I was involved in, and led, community development work locally through projects like Homework clubs for kids to support parents newly emigrated to the UK,

established and cared for community gardens that helped those recovering from substance issues and provided growing space for those in a city area that had limited green space where our surplus produce went to a community learning kitchen for refugees.

Helped support women seeking asylum groups meet and share their stories.

Regenerated alleyways through arts projects and lead community mapping projects that celebrated the local community ecosystems.

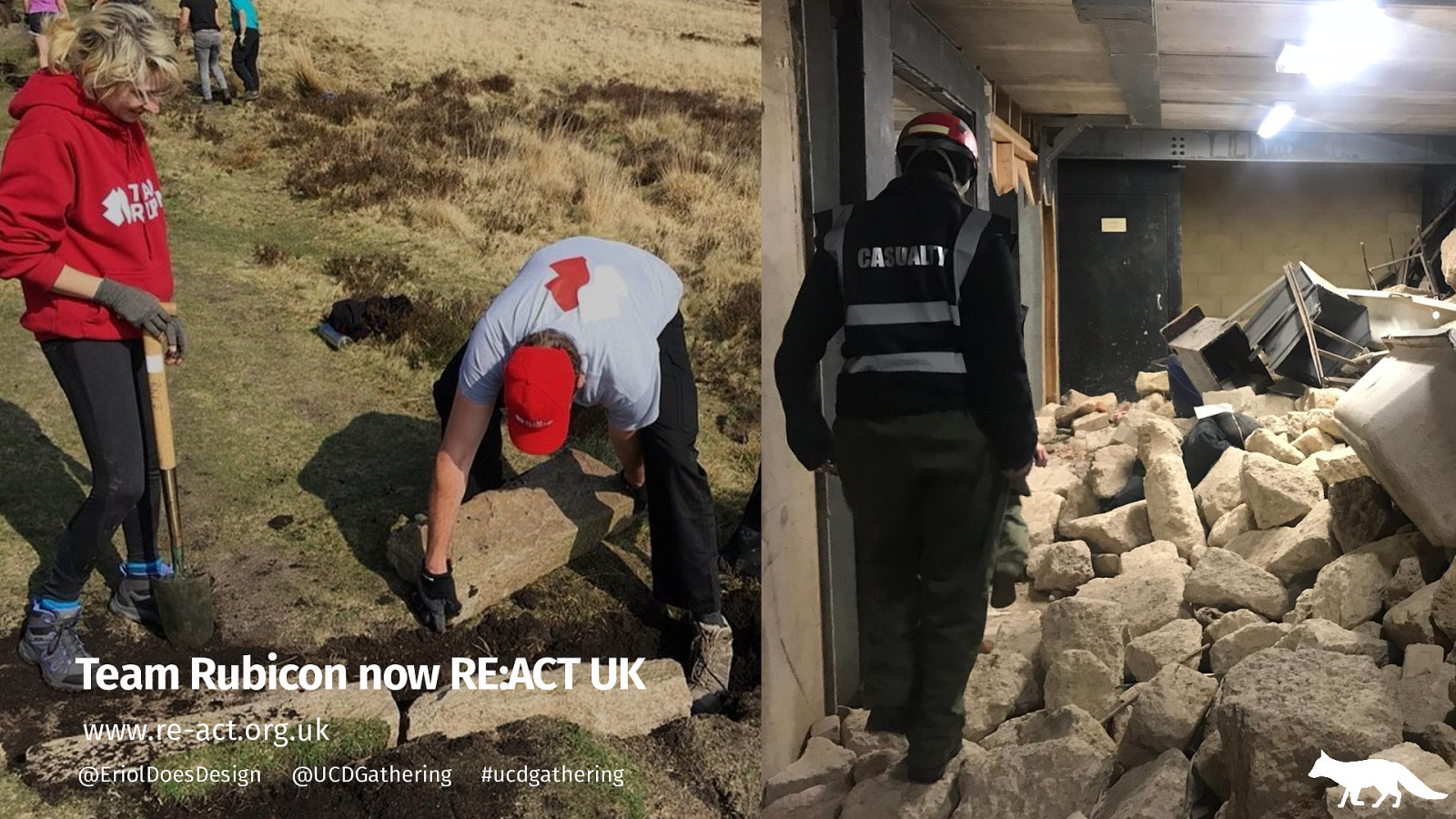

More recently, I’ve been involved with RE:ACT UK (formerly Team Rubicon UK) with domestic (UK based) disaster response and prevention. Including serving for the first wave of their ‘operation RE:ACT’ covid-19 response here in the UK.

But I didn’t start out being human rights centred. With the various work I was doing personally and professionally, I was still compartmentalising and not ‘centring human rights’ in my work. But I remember strongly the first big ‘nudge’ towards centring human rights in my work.

In 2017 was working as a designer shortly before joining Ushahidi, in a ‘tech for parents’ start up. They made a useful product and had a good mission to help parents and kids better talk about the time spent on devices and curb ‘screen addiction’.

I had asked during my interview and wondered in my first few weeks whether the young people being monitored and limited through their devices always truly consented and how that power was exercised by a parent.

I asked ‘Has there ever been a case of abuse? where a parent has stopped a kid seeking information that they should have rights to?’

I thought about myself as a younger teen, which was before the internet was throughly used by parents generations, i was finding information about LGBT+ issues and discovering an identity that was mine, to internally to explore and wondered, would I have been stopped from viewing that?

I was assured there were policies and considerations being taken and I was placated.

Then a customer support request came through a friend of a woman was asking how to remove the app because their friend’s partner was using it to monitor, track and control their device and communication. The team was asked, what should we do? How should we respond? what was our responsibility here?

There was quiet kind of panic, one that happens when something you’d hoped to never face arises. These kinds of problems are ones that keep you awake at night thinking what if?

We talked as a team, how do we address this? Some were more involved than others, citing company policy of ‘only she (the abused partner) can request the removal of the software with his (the abuser partners) consent. So the friend asking on the abused woman’s behalf was not in a great place to support her abused friend. Can we delete the accounts, can we block them? Lots of ideas on how to ‘solve’.

I spoke up, as a person who had experience of partner abuse and said, doing any action to rouse suspicion for the abuser could put the woman in more danger and we can’t know what might happen if we suddenly remove the tool of control. We need to support the friend and woman to get to a safe situation before doing anything that could result in violence. I worked with the customer support rep, to find the closest charity organisation that could ensure safety before any technology solutions could be attempted.

Was this enough? we’ll never be sure and while I attempted to have conversations afterwards about safe guarding others the issue was largely ignored as an anomaly an ‘Edge case’.

So, everyone I’d like to ask “Have you had a similar experience? Was there a moment that made you pause with concern?”

You can answer if you wish.

We’ll pause for a few second for people to respond should they wish.

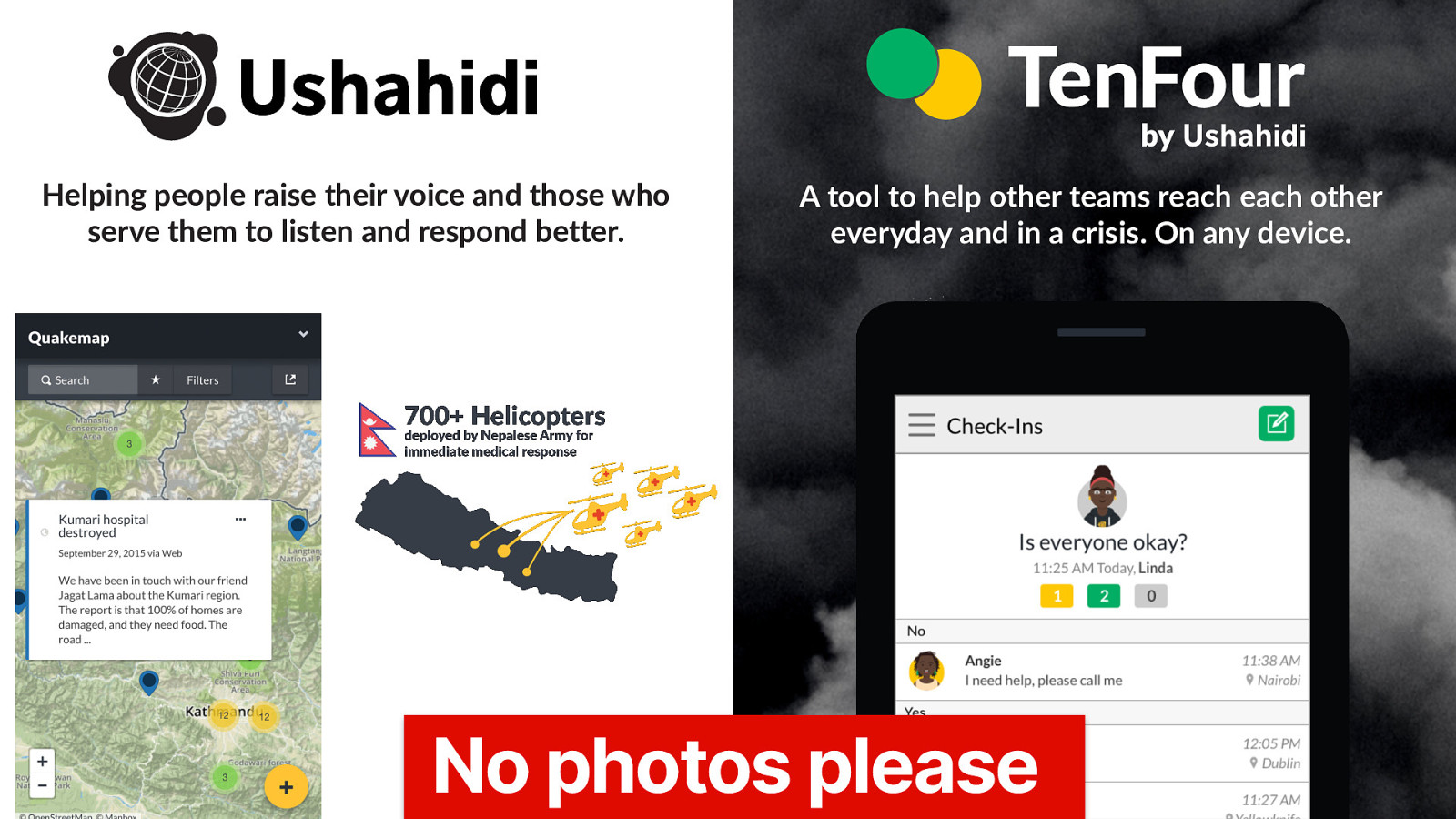

Ushahidi is a Kenyan NGO that makes humanitarian, Open Source Software technology for human rights.

Founded in 2008 in the aftermath of election turmoil in Kenya Ushahidi’s mission and subject matter expertise is in building varied communication technology to empower people to raise their voices while delivering tools to help organisations better listen and respond to those people raising their voices.

Ushahidi platform is most commonly used for disaster response, election monitoring and human rights abuse reporting.

To describe what is visible on the screen right now is a screenshot of ‘Quake map’ showing a report of a hospital being destroyed during the Nepal Earthquakes. and a small graphic showing that 700 medical response helicopters were deployed by the Nepalese army from this Open Source collected citizen information.

There’s also an example of Ushahidi’s emergency communication tool TenFour, which was created after the Westgate Mall terrorist attacks in Nairobi in order to aggregate communications in crisis situations.

While at Ushahidi as a designer I worked across projects building and improving the OSS tech for cases like how to improve access to healthcare and reduce HIV/AIDS in adolescent girls and young women, build resilience through mutual aid and community support in crisis and disasters and improve peace building and education across communities in East Africa.

With the efforts that I’ve made to centre human rights in my professional and personal life you might think that it’s easy to integrate and advocate. It’s not, it’s difficult due to multiple factors, but the pressure of design and tech to sideline human rights as a focus is one of the hardest parts.

This snippet is from a conversation between myself and Kat Lo, who is Content Moderation Lead and UX at Meedan (https://www.linkedin.com/in/katherinelo/) and fellow human rights centred designer. We were speaking about how we struggle to not prioritise human rights in our work.

The snippet reads: “After designing for some of the most extreme human rights circumstances, it became extremely difficult if not impossible to not centre human rights our design approach.”

Back in 2018 was attending a team ‘sprint’ where we’d travelled to a location to work on our OSS projects feature roadmap and plans for the coming year. I was reasonably new to the team and we had good relationships with foundations of respect.

However, like many tech teams, we often got excited and carried away when discussing features and improvements to our technology. We were working on a crisis communication app where people can send and receive messages in dire situations like terrorist attacks, natural disasters and similar events.

We we gathered around a table and I was stood off to the side, In groups I tend to be quieter, contemplative, listen and absorb information.

The particular feature we were talking about was being referred to as ‘panic button’. The idea made sense, a way for people in these dire, dangerous situations to more easily send messages to contacts. But when we started to draw and sketch ideas we started to envisage this large red button filling phone screen that said ‘panic’…

The team were excitedly talking about how it could function ‘And the user will just tap this big panic button and a message will be sent here and here and the configuration of it can operate in this way…’

A thought occurred to me suddenly, ‘What kind of person would hate to see me push that big red screen filling button?’ ‘What if I was in a hostage situation and needed to be more subtle?’ That reminded me of how people who are in situations of control might need to send subtle, careful messages to stay safe. How can this still help the person who needs help, but be discreet in certain situations? What if this actually hurt someone rather than helped them?

I gently stopped the energetic conversation and explained the case of someone that might need to be more discreet with their ‘panic button’ need and that a panic button isn’t inherently a bad idea but executed poorly could harm as much as it helped. Could we then, consider this under multiple circumstances and how might we make sure those that need subtlety are cared for. I used the two examples that came to mind, a hostage situation and a domestic violence situation. One of these I had more experience with than the other though I knew what it was like to be held in a single space through threat of violence.

The team were quiet for several seconds, the excited energy calmed and felt uneasy for a moment. Until the team processed the examples, began to consider this approach and we were guided back to a space that allowed excitement but with added care for the complexities of the humans we were building for and all the aspects that may be unknown to us.

As humans with broad and varied experiences we often have access to insight and information ourselves that can help us pause and consider our approaches.

Question: Have you given or received information about a difficult subject in your design work?

How did that situation play out?

Let’s return to that conversation with Kat Lo about finding it difficult to remove ‘human rights’ from our thinking and ask ourselves

and why should I?

Though the problems in tech are minimised through ‘edge cases’ we can remind ourselves to centre humans their rights and their safety in our work.

Often designers are asked to work with those that use the tools we create, through research and participatory approaches we learn and experience what our users go through in order to better represent and advocate their needs. Though often these processes touch upon deeply personal topics.

I was working on a project with a large and varied team around the role of technology in peace building and peace education. The goal, was to better understand and build tools that helped those advocating for peace in societies and communities that faced violence and crisis.

In the research part of this project we were asked to do a number of design activities one of which was journey mapping. Where, with users you map the events, actions, thoughts and feelings of a time period. You may have seen or participated in these before. The main difference here was we needed to understand what happened during a violent incident to better prepare technology tools for those incidents.

The idea of journey mapping what was essentially, peoples trauma didn’t sit well with me and I had not come across methods and processes to properly care for people whose experiences could still be harming them now but i knew the typical method would not be sufficient.

I spent a lot of time with my two closest workmates on a way of meeting the needs of the project while introducing care and ethics into the exercise. I used my own understanding of traumatic experiences to consider an adapted approach.

At this point I’d like to introduce Polycom Women.

Polycom women are a group of women across many generations and backgrounds dedicated to peace building in Kibera (informal settlement or ‘slum’ in Nairobi, Kenya). They undertake a number of different peace building activities in their area including peaceful protests, skills growth and speaking to and engaging with youth on multiple difficult topics.

Working with Polycom and the other attendees at these workshops about peace was one of the first times I was confronted with my own experience of trauma as well as other peoples and how to manage that in a design research context for technology.

We met Polycom women before our workshop journey mapping exercises, and I remember how casually these women spoke of being harmed as the peacefully protested and attempted to continue their peace building work.

It was at this point I knew that building tools and process for people that have and are traumatised, means better understanding your own perspective on trauma and experiences of trauma.

Before our activities, I went through the same exercises I would be asking people to do for us and, as I asked them to detail their experiences I first shared mine with them.

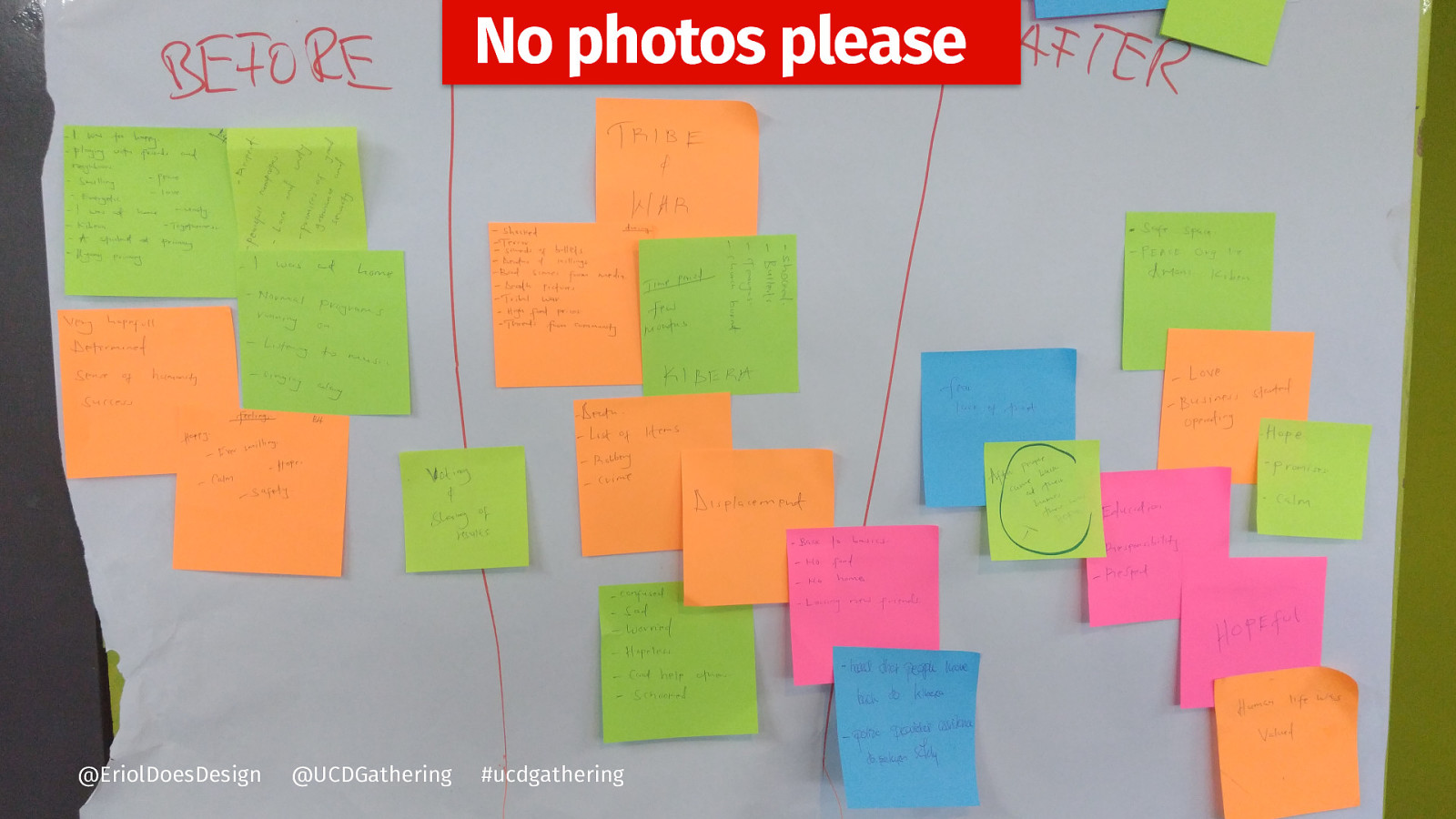

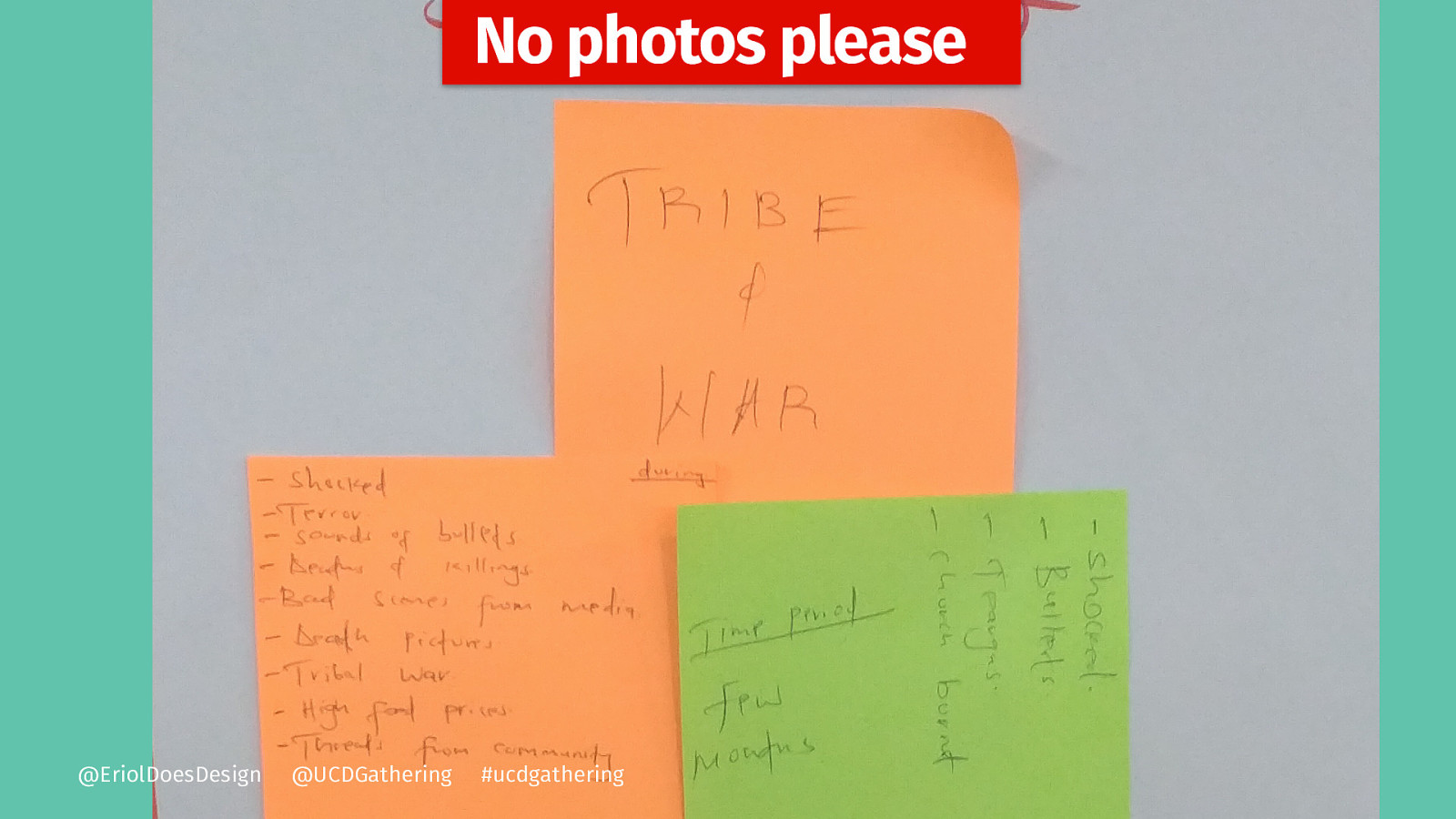

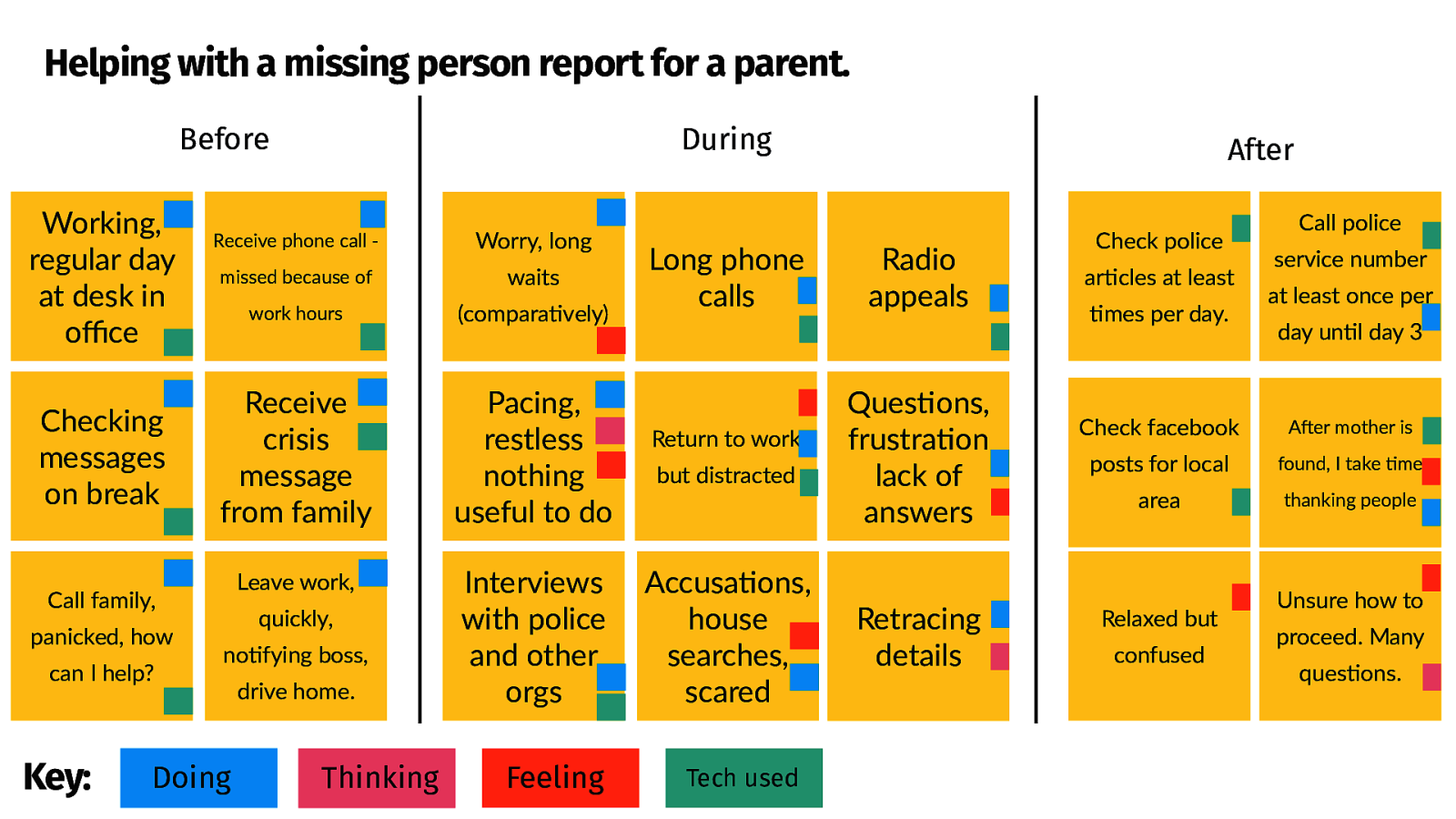

Here’s an example of a journey map from a participant.

It’s separated into before the incident, during the incident and after the incident.

On close up, you can see elements from the participant/s showing events like ‘war’ ‘tribal conflict’ ‘high food prices’ and ‘sound of bullets’

Though my own incident journey maps had different content, the sentiment was the similar if not the same,

Sharing of experiences that may have shaped a part of you in order to better understand how we might improve. Each of the team involved in the project was asked to do this exercise themselves but there was no obligation to have these used as an example.

This allowed us as a research group to better understand and connect with the people we were going to make tech for.

There were ways we ensured that what we did was as ethically as possible.

~ Researchers went through the same process ~ Researchers examples used in workshop for compassion ~ Attendees notified pre-workshop of subject matter ~ Psychological support on site ~ Confidentiality ~ Researcher supported post workshop

After these two stories I’d like to ask, Do you think your organisation or projects could benefit from talking with those that are most harmed by what you create?

At this point I’d like to say that, the Polycom women and other people doing peace activities weren’t using specific ‘peace advocacy’ only technology, they were using facebook, twitter, SMS, Pen, paper, computers, websites, CMS’s. Many tools of many kinds.

Journey maps are powerful activities that you can keep for your own use or if you feel happy to, shared with those you work alongside or even made open.

I’m going to ask you to think of a deeply upsetting event in your life and, like with the previous stories participants we’ll begin to journey map this event.

Doing this activity is optional and not advised if you are still affected by this event and would need recovery after revisiting the subject matter during this activity. Instead you can listen to my examples and follow along. If you are creating a journey map about an event that if discovered by someone could result in harm, I recommend destroying the journey map after the exercise or abstaining from this exercise.

For those listening and not participating, there will be pauses of silence while I offer time for those participating to write, reflect and work with their material.

You’ll need some paper and a pen or an open digital document.

At the top your ‘page’ write a brief sentence pr key word about what you are mapping. My example will be ‘PTSD flashback while using google sheets during an online meeting’ but you can choose to describe your upsetting event in your own way. There’s no competition here for what is mapped, you choose what you want to map to explore. There is no hierarchy in your own experience of upsetting events.

Separate this into 3 sections add the title on the first section as ‘before’ the centre being ‘during’ and the last being ‘after’.

Before can be a time period of your choice, I recommend no longer than days before the event. Hours and minutes are also good to explore. During are the actions and events that happen as the upsetting event is happening but again, you choose the time boundary of the ‘during’ phase. The after section is, like the before section where you describe what is happening after the upsetting event. Like the before section, this can be in days, hours or minutes.

Try to write short statements, sentences or words that describe what you were ‘doing’ what your were thinking and what you were feeling an example might be ‘I was calming shopping out with friends in the mall’ or ‘I was thinking about about a worrying post on my friends social media that morning’ or ‘I was feeling tense and stressed’

In my example, I use colour codes and words to assign the attributes of ‘doing’ ‘thinking’ ‘feeling and the ‘tech used’. You can write symbols, words or use colours.

As we map these upsetting events, it is interesting to notice when we have used technology as part of this event if we’ve used technology at all. Here we begin to weave the thread between our very human experiences and the technology we use.

Finally, before I head into my example the purpose of this guided exercise isn’t to finish a perfect journey map, it’s to explore a personal experience, should you choose.

So we’ve been through one exercise that could be useful in centring human rights in our design, open source and technology work, but there are so many more.

There are two other activities I’ve learned from others in the human rights centred design, and tech for good communities that I’ll briefly share with you all.

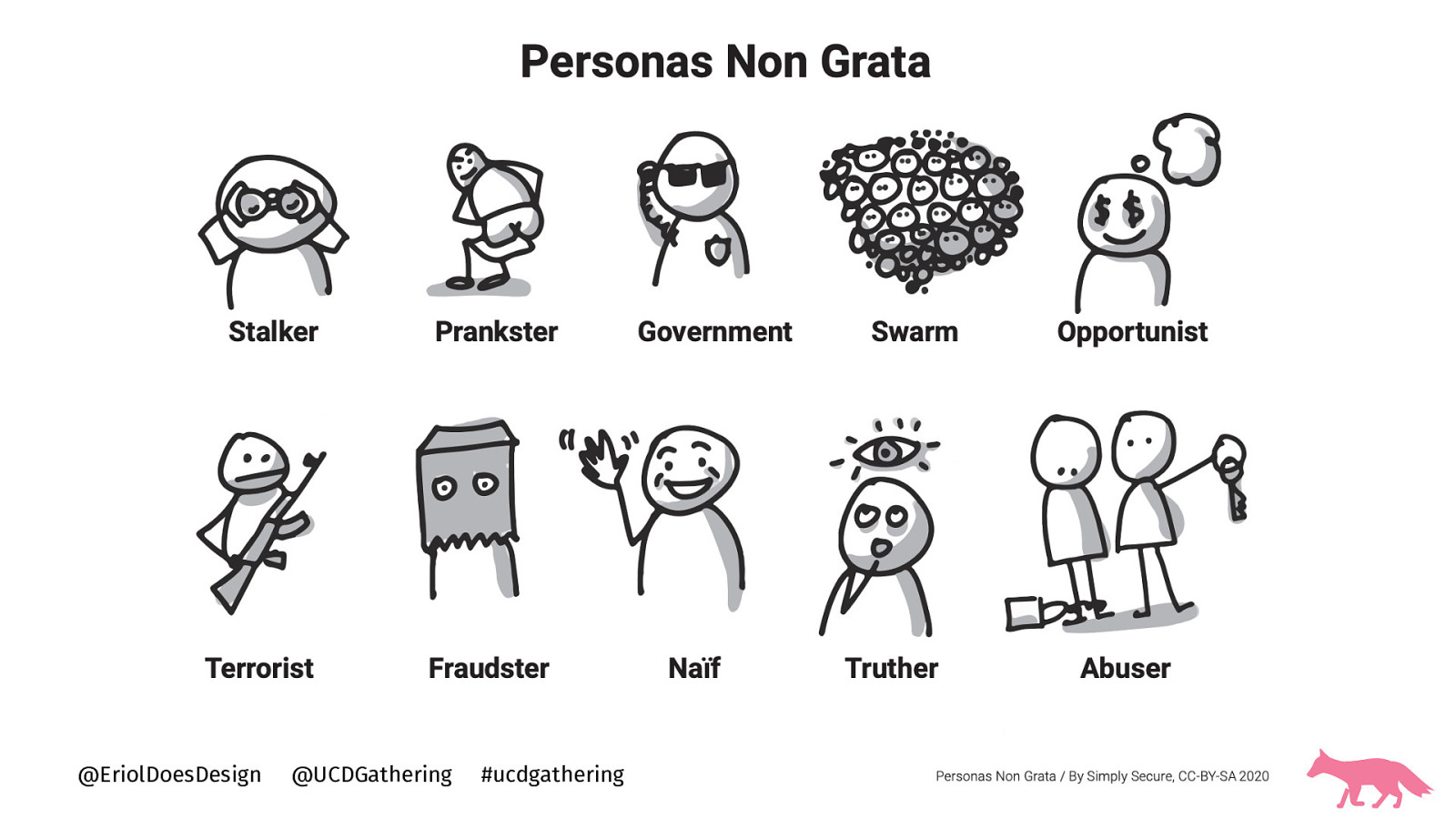

Persona non-grata Molly Wilson of Simply Secure. https://simplysecure.org/designunderpressure/

Red team vs Blue team Jonny Rae-Evans of Snook. https://bit.ly/redblue-JRE

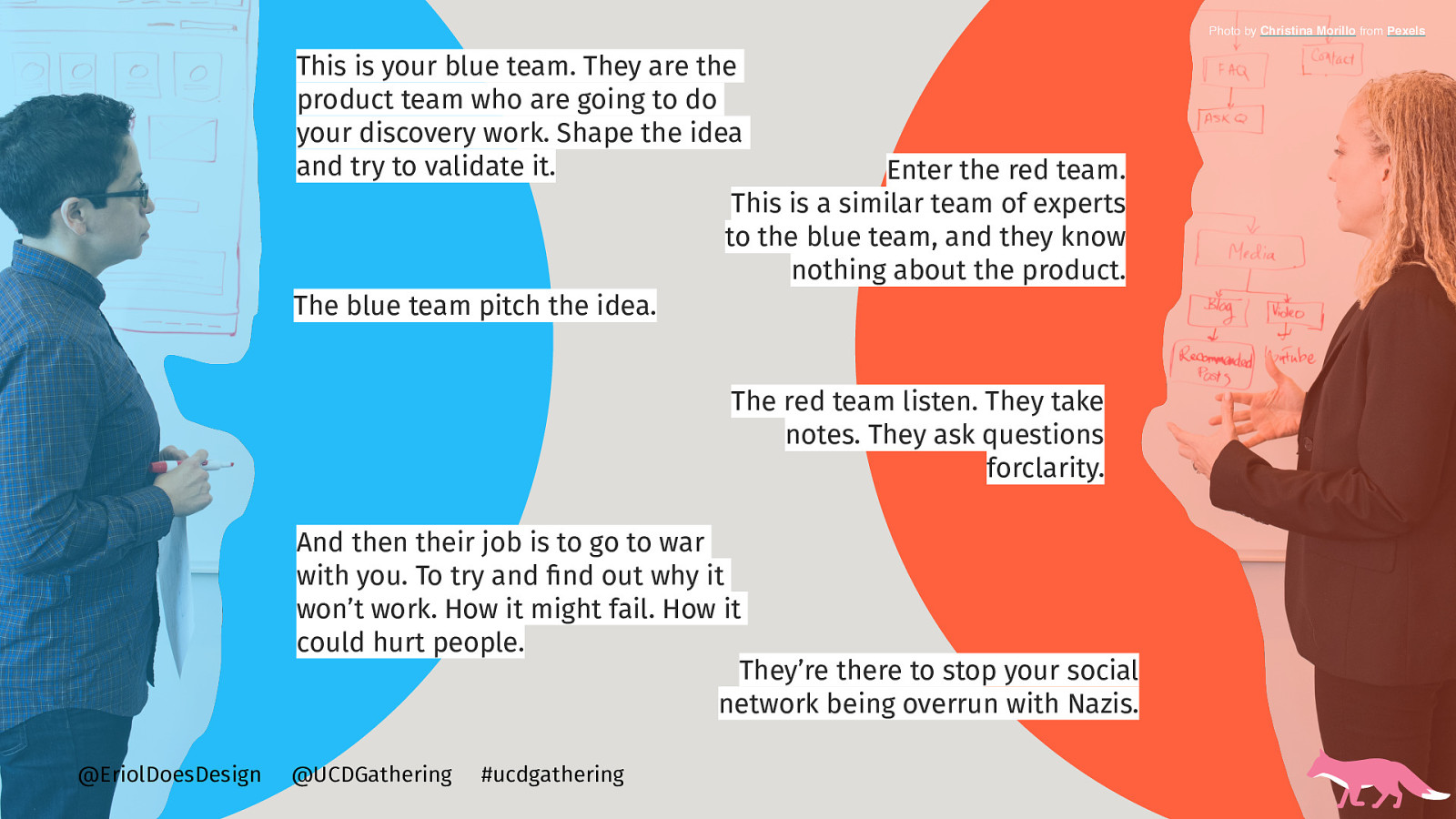

You may have heard of red/blue teaming in other technology contexts.

These ten “personas non grata” are people you probably don’t want in your product or service, but who are likely to find their way in anyway.

The idea of the persona non-grata exercise is to explore how or what these personas could be doing with your tools and open source to better mitigate the potential problems.

https://designunderpressure.glideapp.io/

The blue team vs. red team exercise is about applying the ideas of penetration testing to your product discovery processes.

This is your blue team. They are the product team who are going to do your discovery work. Shape the idea and try to validate it.

Enter the red team. This is a similar team of experts to the blue team, and they know nothing about the product.

The blue team pitch the idea.

The red team listen. They take notes. They ask questions for clarity.

And then their job is to go to war with you. To try and find out why it won’t work. How it might fail. How it could hurt people.

They’re there to stop your social network being overrun with hate.

What will nudge you to centre human rights in your work?

Will it be people suffering with illnesses like covid-19 unable to access information about infection risk?

Will it be people who reach out on social media platforms to speak about institutional violence and cruelty?

Will it be those that reach out to you when the tech you’ve helped build has allowed for private files to be leaked?

What about when someone is tracked, monitored and judged for something that they cannot and should not change. Like who they love, what they believe in or how they look.

What if any or all of these were people you know and love? what if these happened to you?

It’s well and good to say you believe in and support human rights and it’s great when folks take that outside their work and roles into protests, policy, advocacy and charity. But why not where we spend much of our lives, our workplaces and tech communities where we make useful tools. You might think of the risks, the worry, the concern for your own stability and peace. But when so much is at stake for everyone, the steps you make to being more human rights focused the more the risks will become normalised and we’ll begin to make human rights centred in our tools.

I like to finish my talks with a plethora of resources. So, If you’re looking for small steps to become engaged with human rights then I recommend reading reports from NGO’s. Here’s some to get started.

Leaving no one behind: Lessons from the Kerala disasters: https://www.preventionweb.net/publications/view/69992

Safe sisters - Digital security challenges faced by women human rights defenders. https://safesisters.net/resources/

The Human Rights, Big Data and Technology Project https://www.hrbdt.ac.uk/publications/

Designing when everyone designs - Ezio Manzini Digital Economies at Global margins - Mark Graham Digital Witness - Dubberley, Koenig, Murray Digital democracy, analogue politics - Nanjala Nyabola Civic technologist practice guide - Cyd Harrell

If you’re looking for practical resources beyond those I’ve spoken about today, these organisations produce OSS, toolkits, guides and video tutorials for human rights workers, technologists and designers.

And finally, follow our human rights centred design group.

Where we meet and discuss our work as designers working for and with human rights and support the ongoing conversations about human rights in tech design and open source.

Here’s where you can find me on the internet.

On medium I wrote a reflective piece on my own relation to trauma and how it affects my design practice.