Designing Tech Tools for Crisis and Natural Disaster Relief

Hello and welcome to this talk about designing tech tools for Crisis and Natural Disaster Relief

A presentation at Mongo DB.Live in June 2020 in 4 McKissic Creek Rd, Bentonville, AR 72712, USA by Eriol Fox

Hello and welcome to this talk about designing tech tools for Crisis and Natural Disaster Relief

There are content warnings for this talk, there are mentions of natural disaster, fire, famine, floods, hurricanes, earthquakes and terrorism. Please only continue to listen if you’re okay with hearing about these subjects.

I’m Eriol, My pronouns are They/Them

I’ve been working as a designer for 10 years and focussing on humanitarian projects for the past 7 years, most recently with open source tools.

This talk focuses on work done while I was working at Ushahidi, an NGO that makes open source tools for human rights cases.

In this talk we’ll be covering these topics: the background of crisis and the lifecycle of a crisis to give our work context.

The key features of our MVP and What kind of Automation makes sense for users within a tool used in crisis times.

Our field research to test our MVP in Kenya

and finally challenges and Takeaways that hope to help folks listening better understand what we learned.

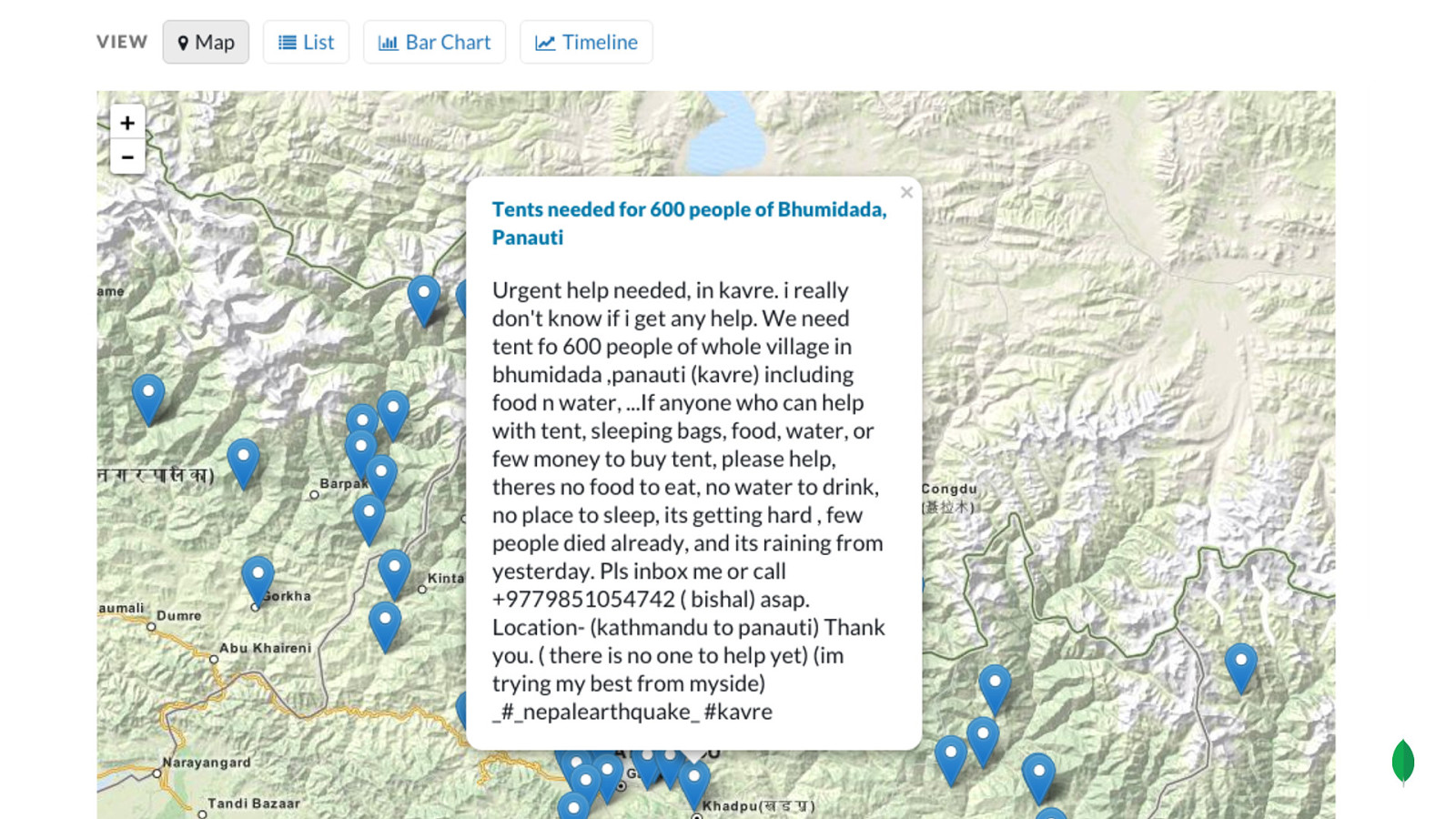

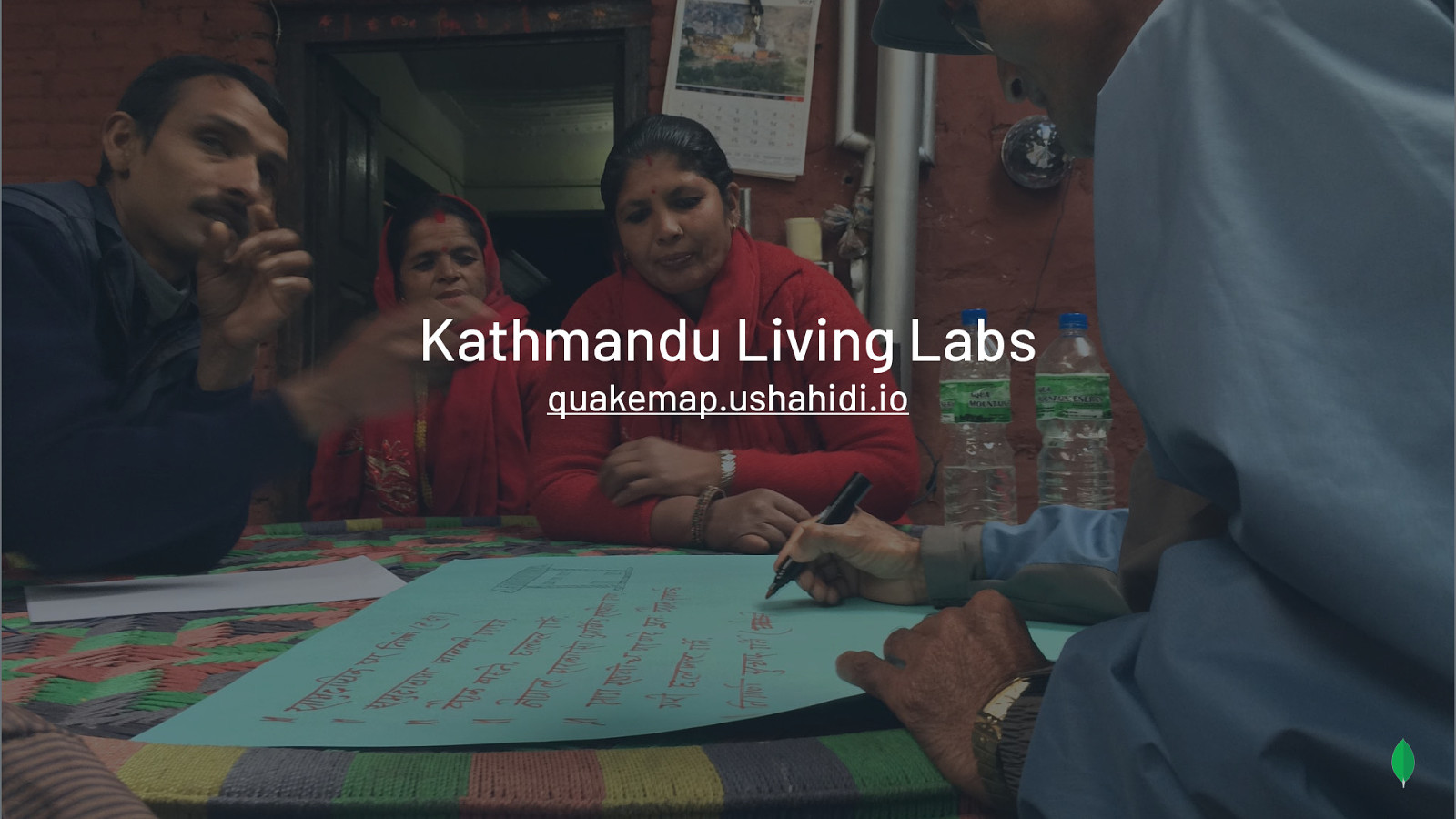

On April 25, 2015, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake devastated Nepal killing more than 9,000 people and injuring over 23,000 people. Much of the infrastructure around the country was severely damaged, leaving hundreds of thousands without shelter or basic necessities.

Using Ushahidi’s OSS tools, Kathmandu Living Labs was able to map all the health facilities in Kathmandu Valley before the earthquake, which undoubtedly helped the relief workers’ ability to deliver supplies and help save lives.

Ushahidi has since helped many humanitarian causes by supporting them in effectively using Ushahidi’s OSS tools to respond to crisis. This includes both natural disaster and human initiated crisis.

On screen is currently a sample of projects supported over the years and where you can see them online.

Kerala Floods irmamiami.ushahidi.io Hurricane Irma irmamiami.ushahidi.io Somalia’s drought abaaraha.org Terrorisim in Kenya tenfour.org Covid-19 ushahidi.com/covid

From our experiences in the various crisis scenarios, we found that this statement rings true, In a Crisis, discovering the needs of people who are affected is complicated.

Sometimes, Multiple aid organisations going in and doing separate, or combined needs assessments. Sometimes digitally, sometimes paper based.

Maybe local NGO’s and partners are involved but not always.

There’s often a top down approach. e.g. We have water and mosquito nets to give out, but what the community might need is reliable power more than water & mosquito nets.

If there’s a political or diplomatic challenge, lengthy application to deploy foreign aid officially can take weeks.

Needs change depending on events. In Cyclone Idai mozambique there was a second cyclone Kenneth that hit a week later so you move from capacity building back to crisis mode.

Focus off of community led resilience response. When aid organisations drop back out after 2-4 weeks the community still struggles to recover.

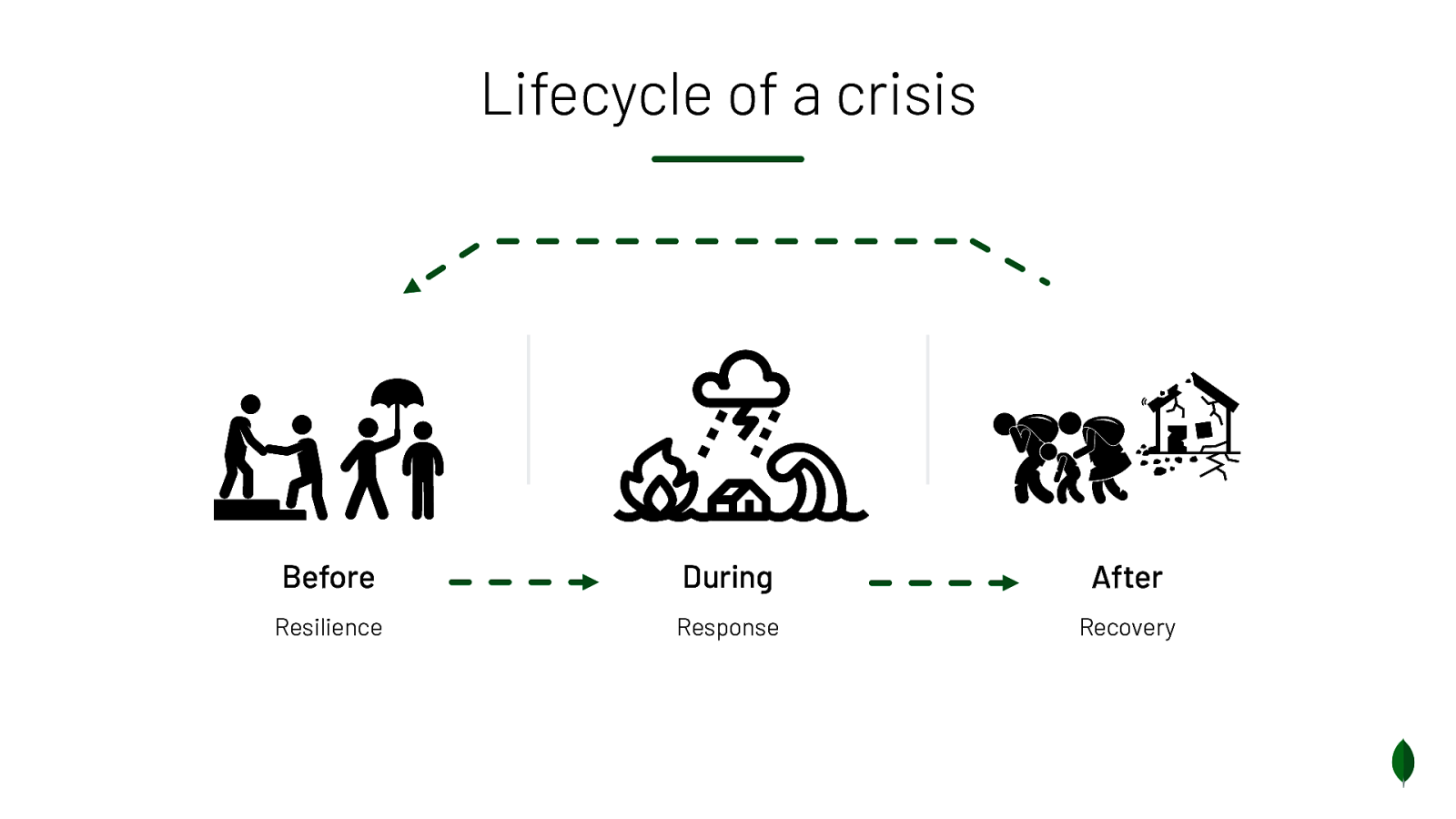

In a crisis, the following cycle typically plays out.

“On the left…in the middle…

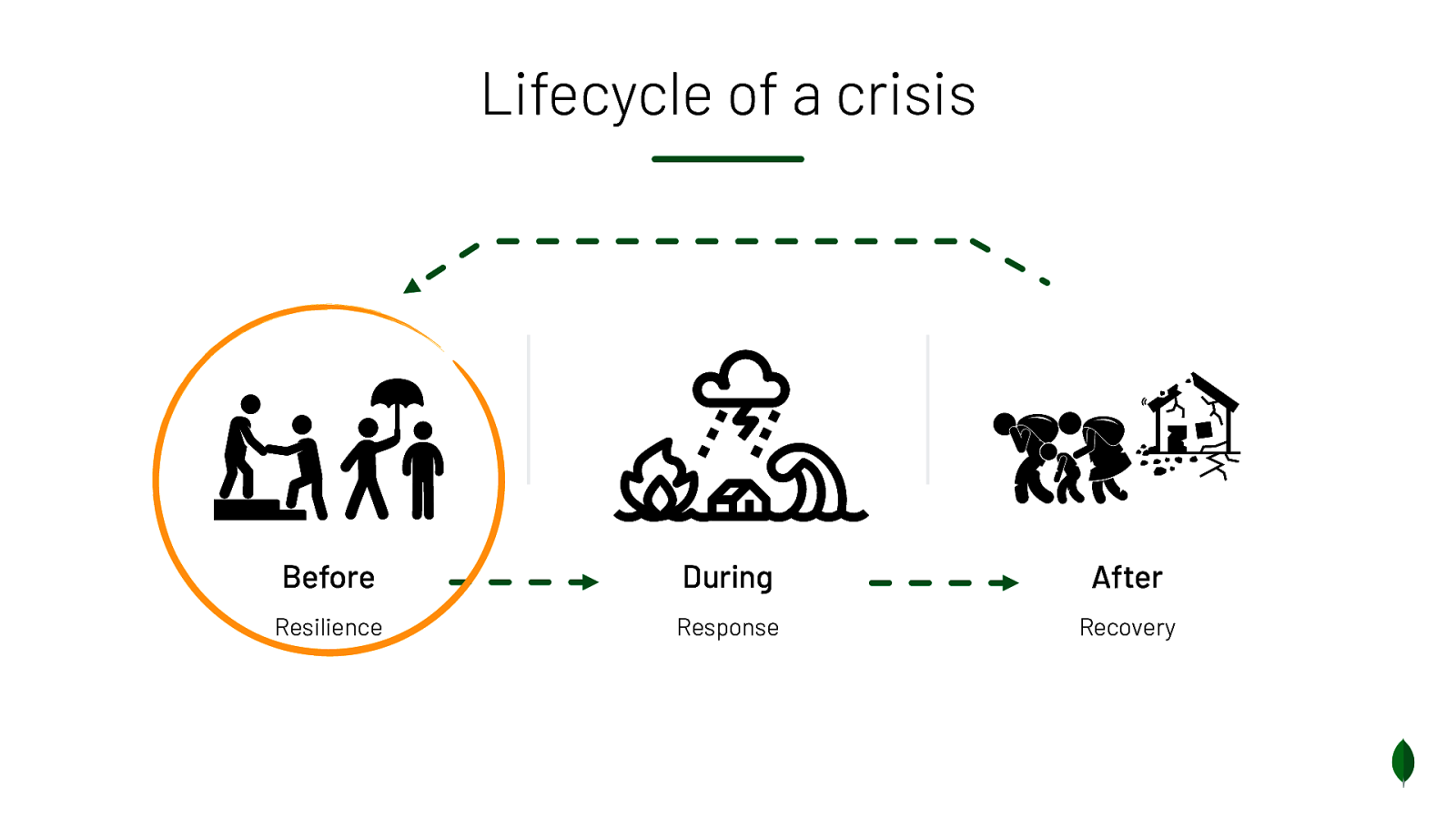

As Ushahidi, we’ve made tools that help with the during/response and the after/recovery phase but we hadn’t really tackled the before/resilience phase in a formalised way.

So this is what we asked of ourselves at Ushahidi.

Can we make something that works in the before phase and then positively affects the during and after phase, connecting up people in the phases of crisis.

To go back to the Nepal Earthquake, we know work is already being done in the before phase when it’s facilitated. The effort there was led by Kathmandu Living Labs but included many other volunteer organisation such as:

Standby Task Force and MicroMappers who organises digital volunteers to deploy in crises to search social media for reports of damage and requests for assistance; process and map this information; and make it available to responding agencies.

Humanity Road - close the communications gap between people and organisations during sudden onset disaster

Translators Without Borders to do the much needed translation effort.

Based off of this example from Ushahidi’s past we sought to find further examples of this social community/volunteer group effort.

We did on site ethnographic research locally to each team member.

We studied Kerala floods, Birmingham floods, Rwanda genocide and tribal violence, California wild fires, Belfast floods and civil unrest and Japan during the tsunami and reactor crisis.

We gathered information on how communities build resilience in the before phases of a crisis: Everything from borrowing cups of sugar to helping with daily tasks to shovelling driveways during heavy snow to paying for expensive medical care when the injured community member could not.

We looked into the formal and semi-formal emergency services too, to see whether there was a connection or overlap in the response.

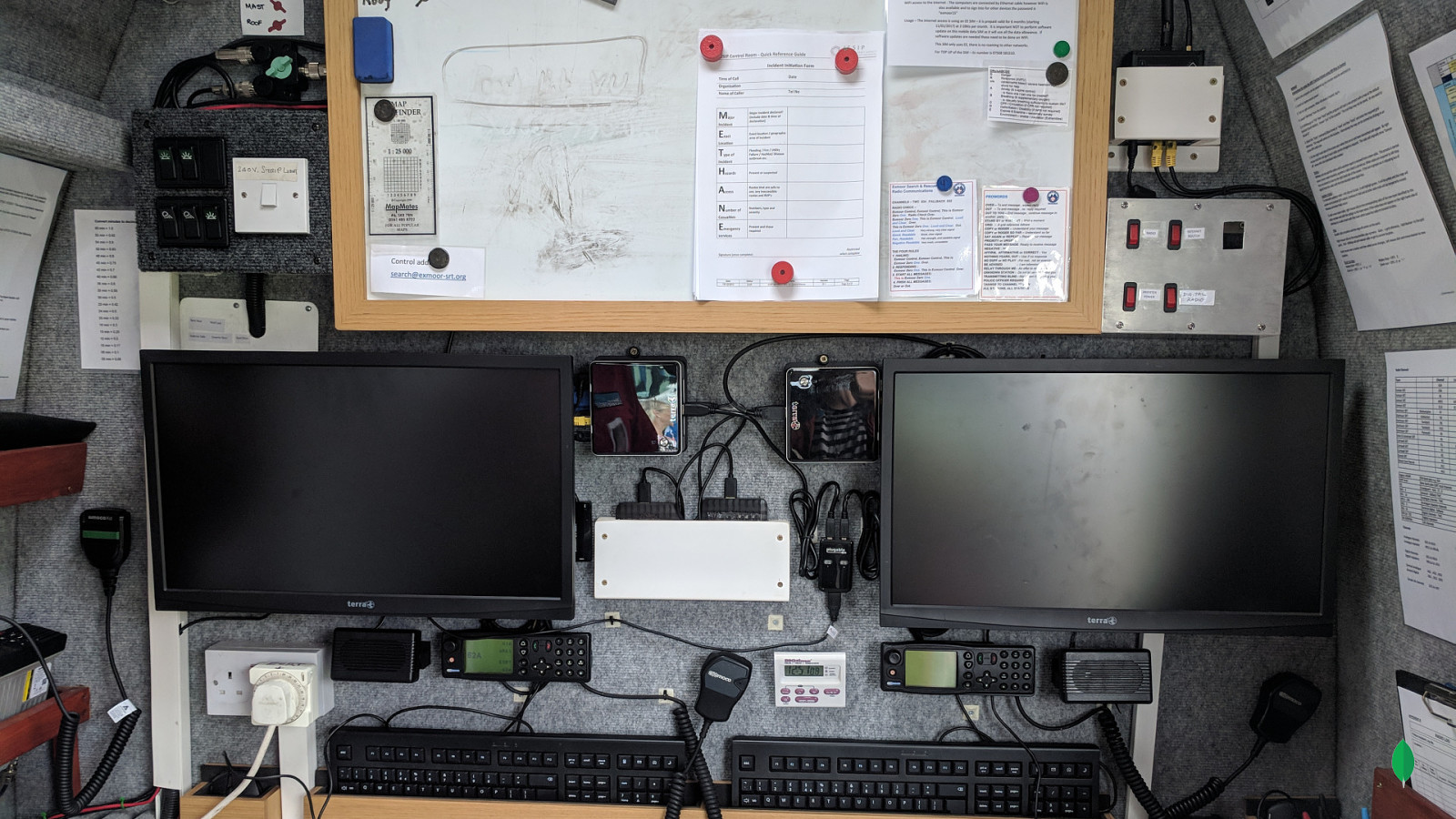

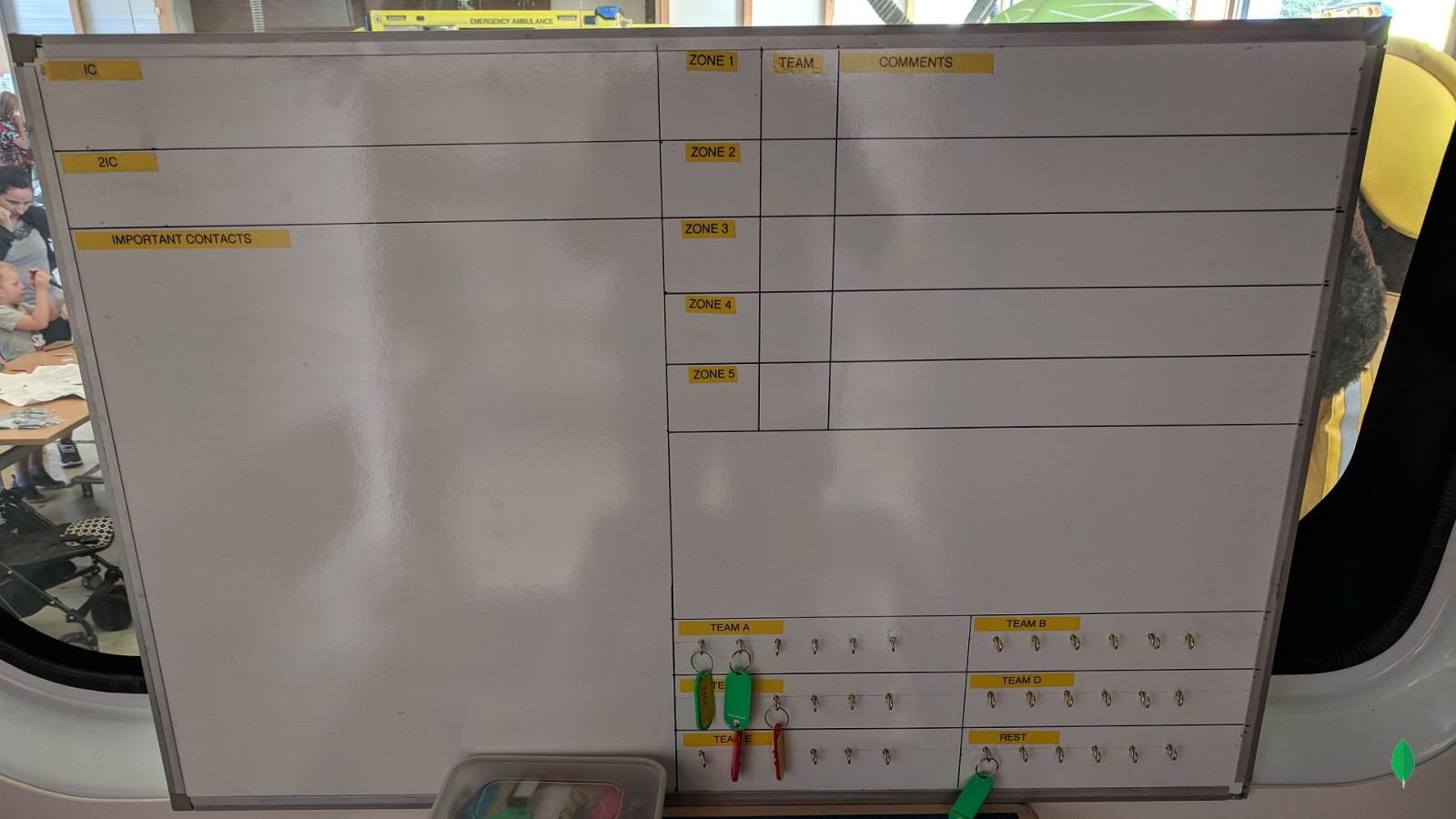

Here we can see a whiteboard, maps, computer screens and communication devices. This is the tech a lot of the semi-formal emergency services were using when doing community resilience work.

We called these people ‘Organised not ‘digital’ 1st’

They use a lot of organisation systems borrowed from formal emergency services. But this approach was not ‘community embedded’ as in communities weren’t using these methods when self organising outside of an emergency services knowledge base.

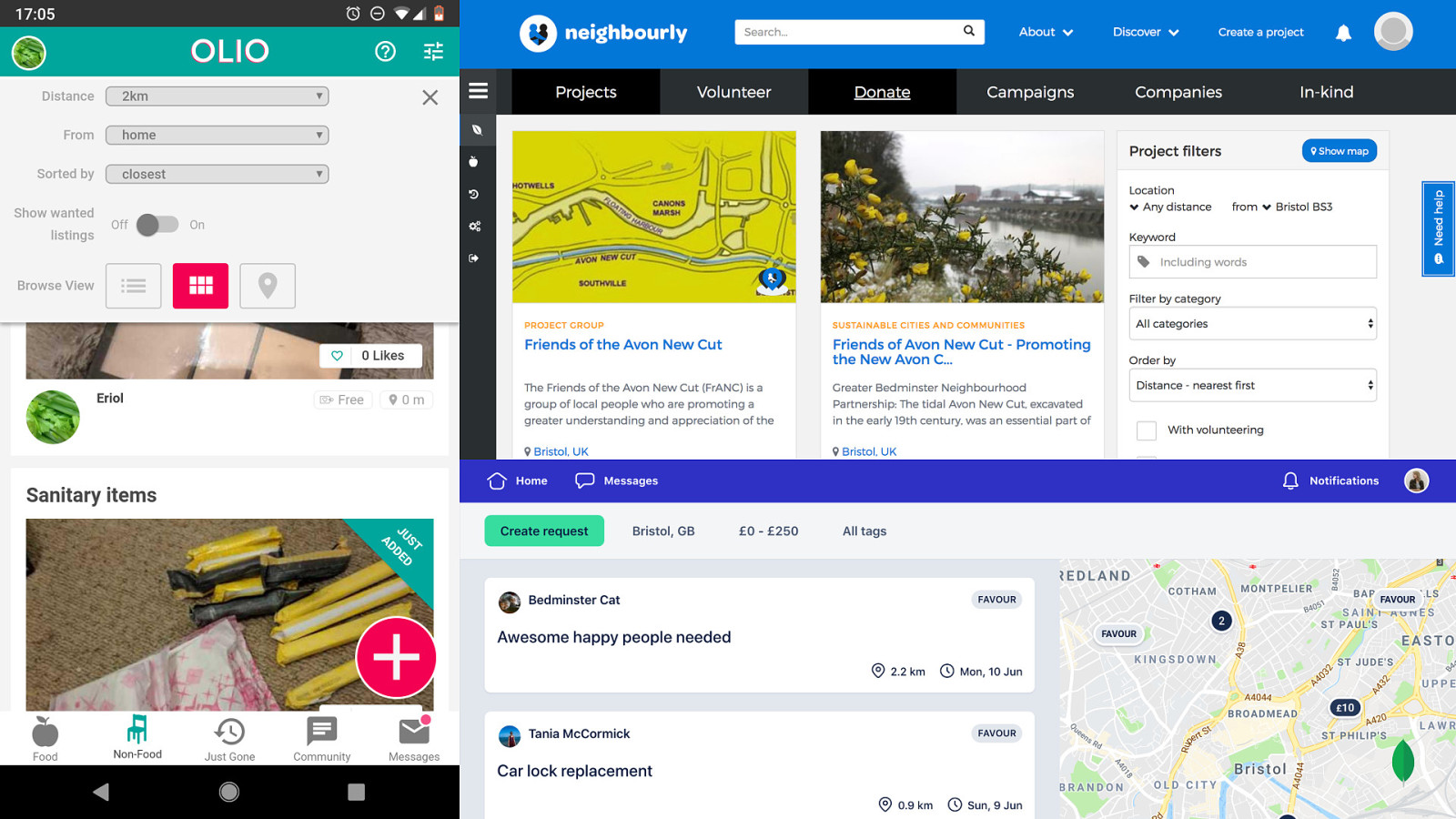

Communities were using tools like Olio, Helpful peeps, Neighbourly, facebook and google drives as well as in person meetings.

But again, those were closed groups and hard to discover if you weren’t actively facing crisis or interested in resilience.

After doing local research, we decided to focus on two key users that were community based rather than emergency services based.

Organised but not ‘digital’ or ‘discoverable’

Digital but not ‘connected to real-life community’

This fit with our ‘community resilience’ focus and Ushahidi’s core organisational aims to empower communities and give them problem solving tools and….

…Because we found you needed a connection in real life to enable a useful digital tool to help build resilience.

When we went to build our MVP post-initial research we narrowed our problem statement and findings down to 4 fundamental questions.

What is the risk? How do helpers/requester mitigate risk to their safety?

Small choices matter What are the micro-decisions you make in a voluntary exchange?

This was the cadence of how we built our MVP over the course of 4 months through to field testing and reporting to our funders.

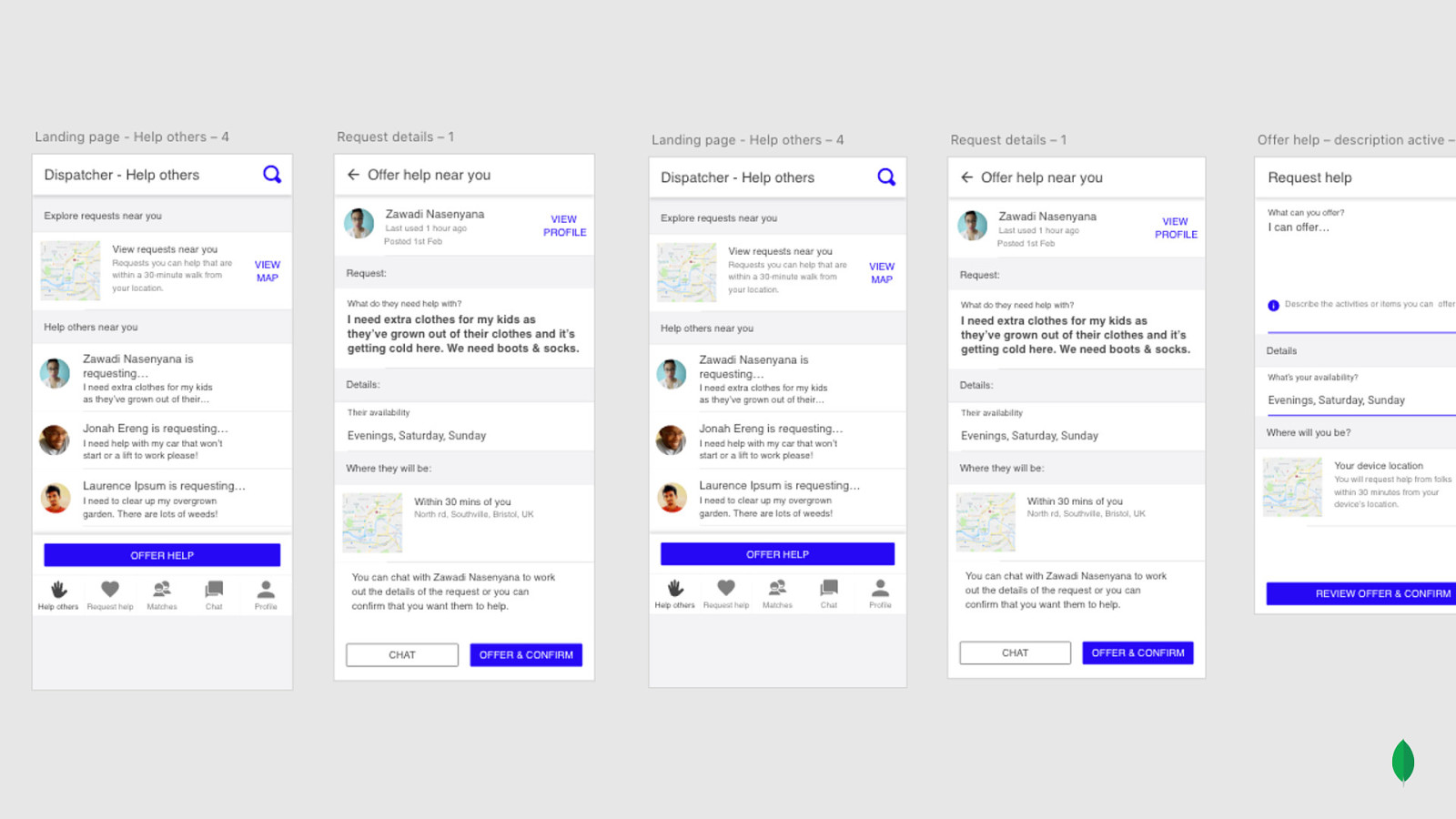

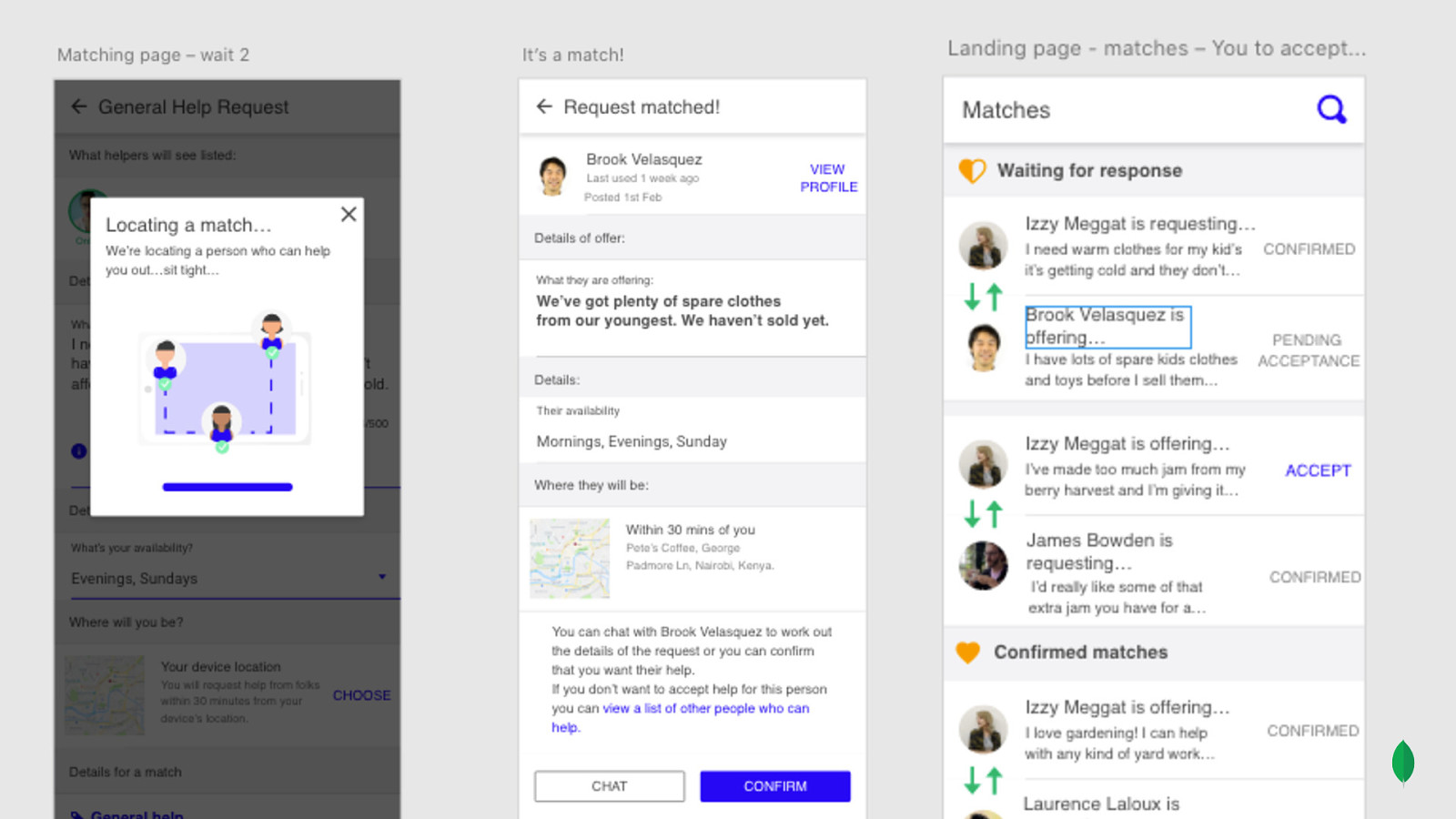

Here are some of the flows of the prototype where we began exploring automation and matching

Regarding Automation, we believed that automation offered a new way of helping ease the pre-existing problems that official crisis relief organisations have and also allows new and existing people in communities a chance to discover those outside of their current ‘circles’ thus extending the potential reach of recovery and resilience post-disaster.

This manifested for the MVP with community matching.

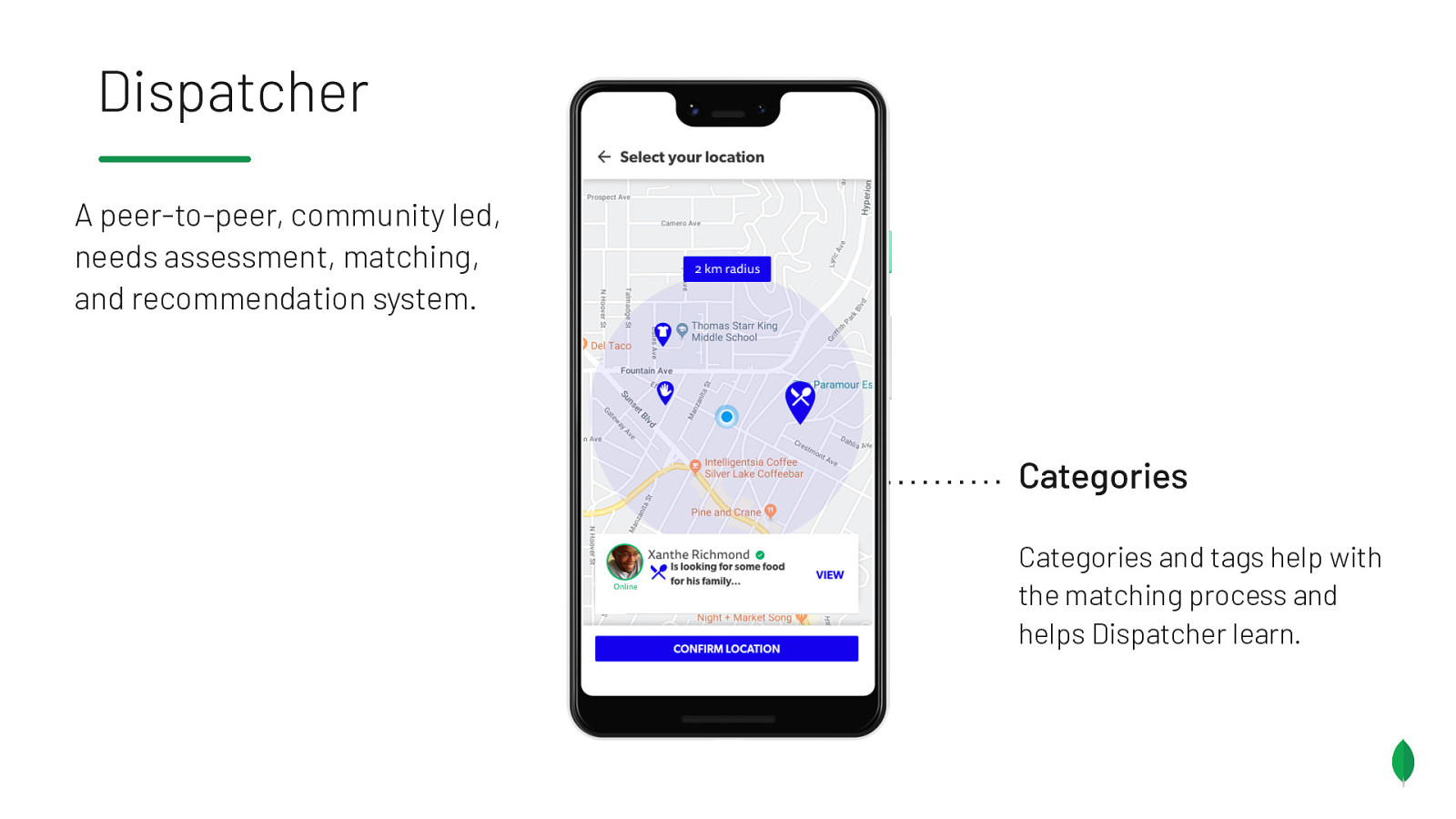

Just to take a moment to cover some of the other key features of Dispatcher that we developed based off initial local research.

Categories/tags Categories and tags help with the matching process and helps Dispatcher learn.

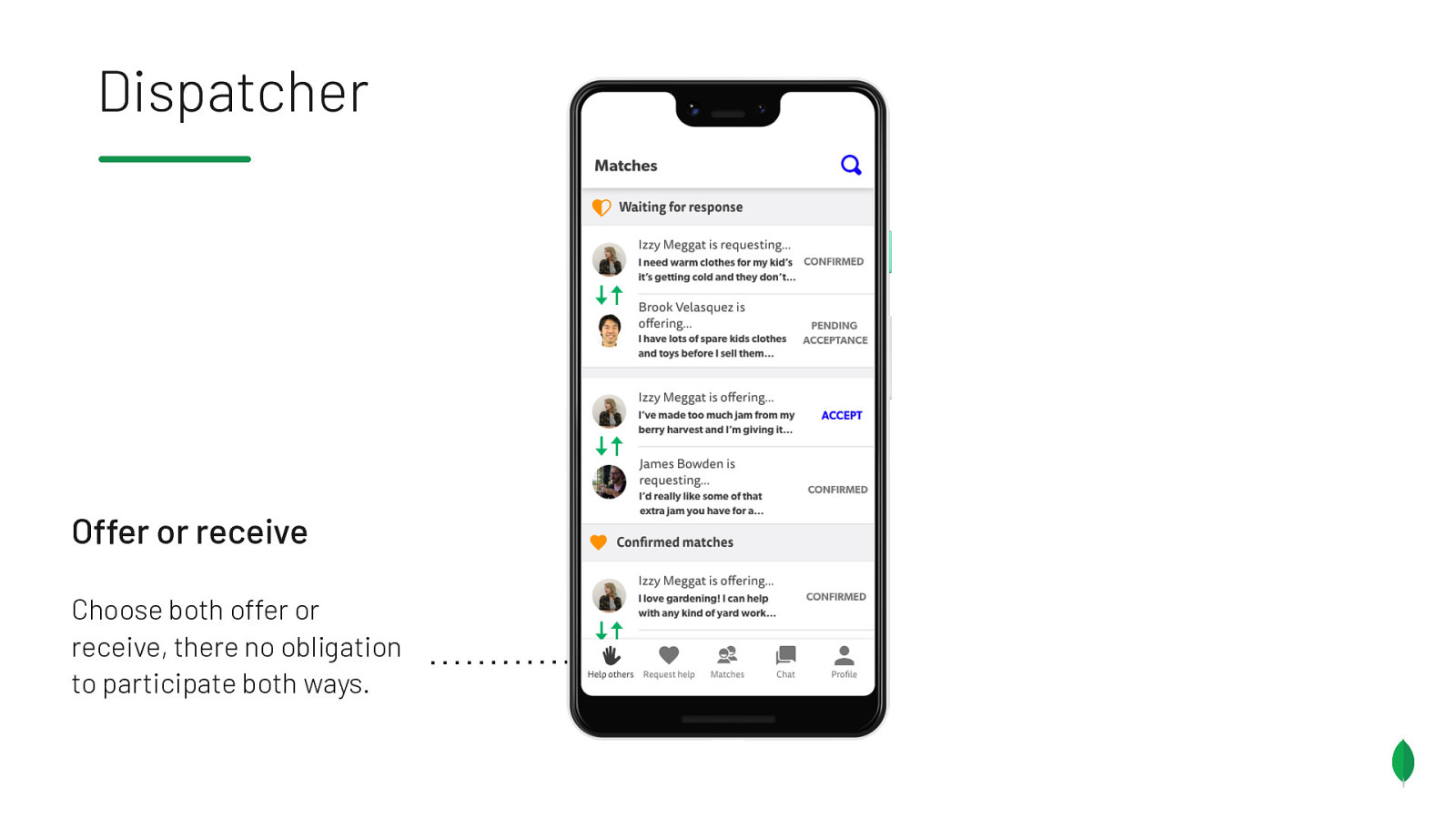

Some people receive and some offer and some both offer and receive.

To require both in this system would actually isolate those that need help and cannot offer the same back. There cannot be a quid pro quo here not when people are battling crisis.

In future crisis people who were helped could offer help and people offering help could be helped. giver and reciever are not always constants.

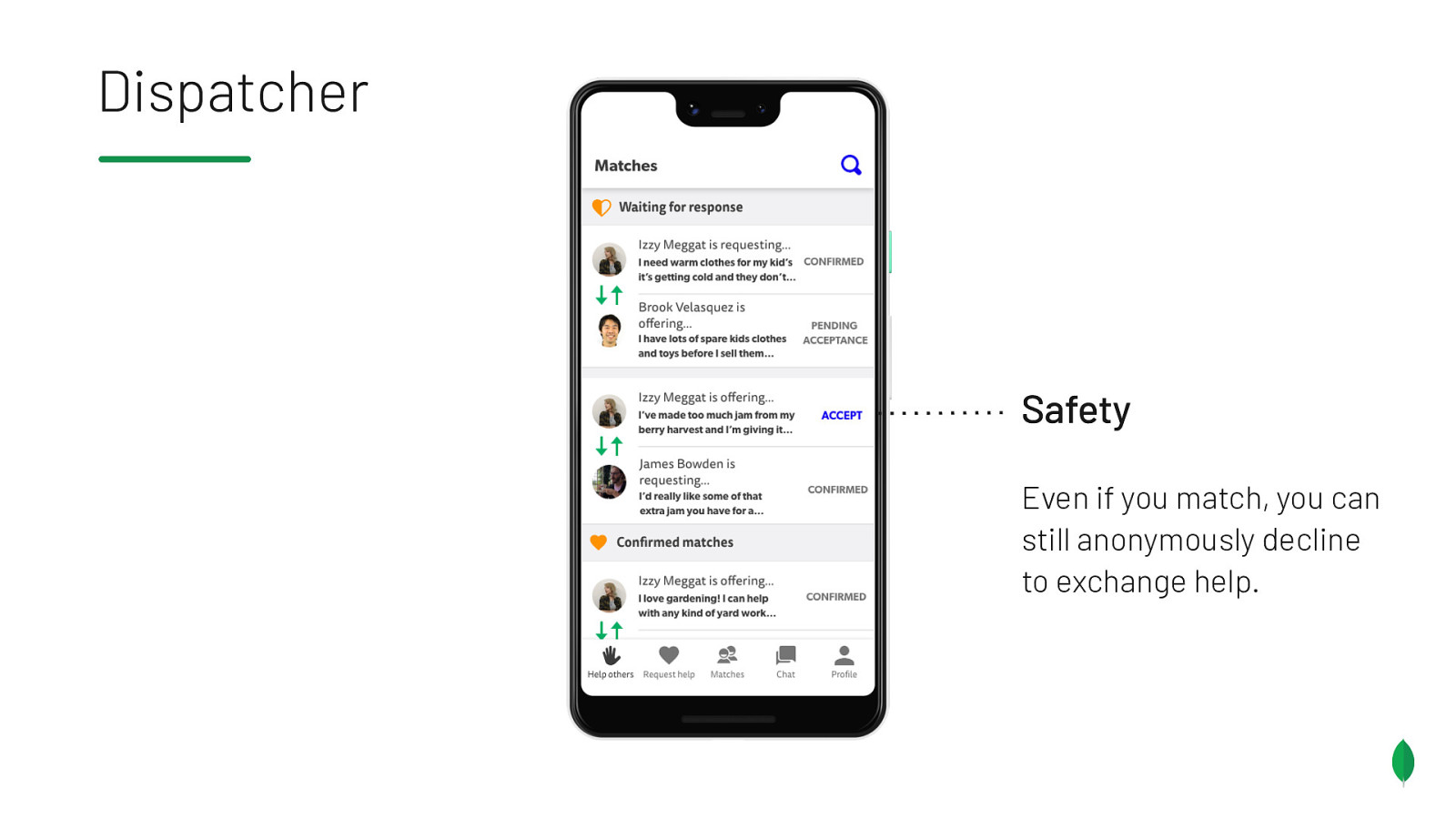

Safety Even if you match, you can still anonymously decline to exchange help. Safety and anonymity was of crucial importance for those with very vulnerable circumstances. Ability to decline anonymously helped this.

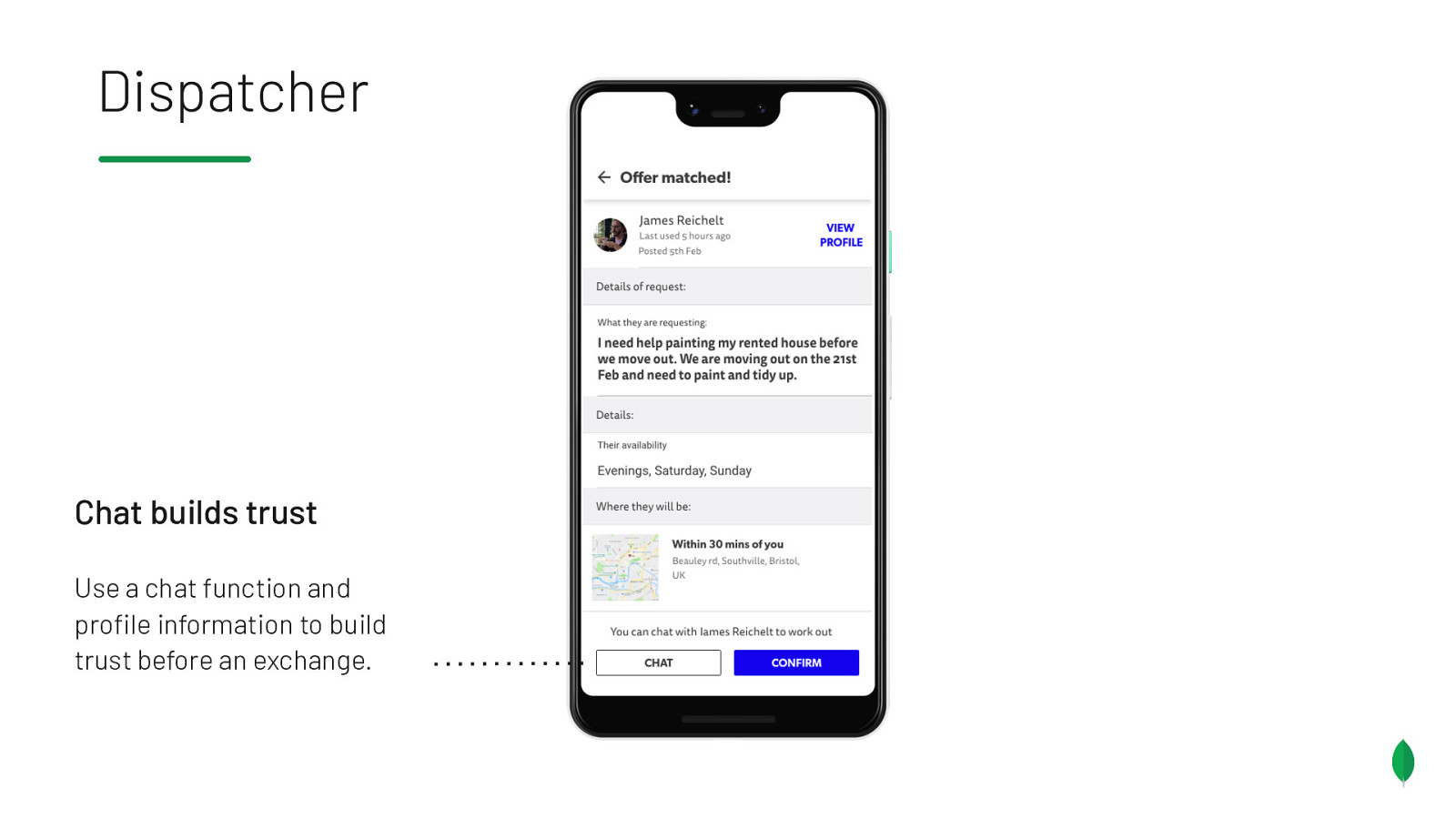

Chat builds trust Use a chat function and profile information to build trust before an exchange. Building a sense of synchronous trust via chat functions gave individuals the ability to make judgement calls.

Now onto our field research

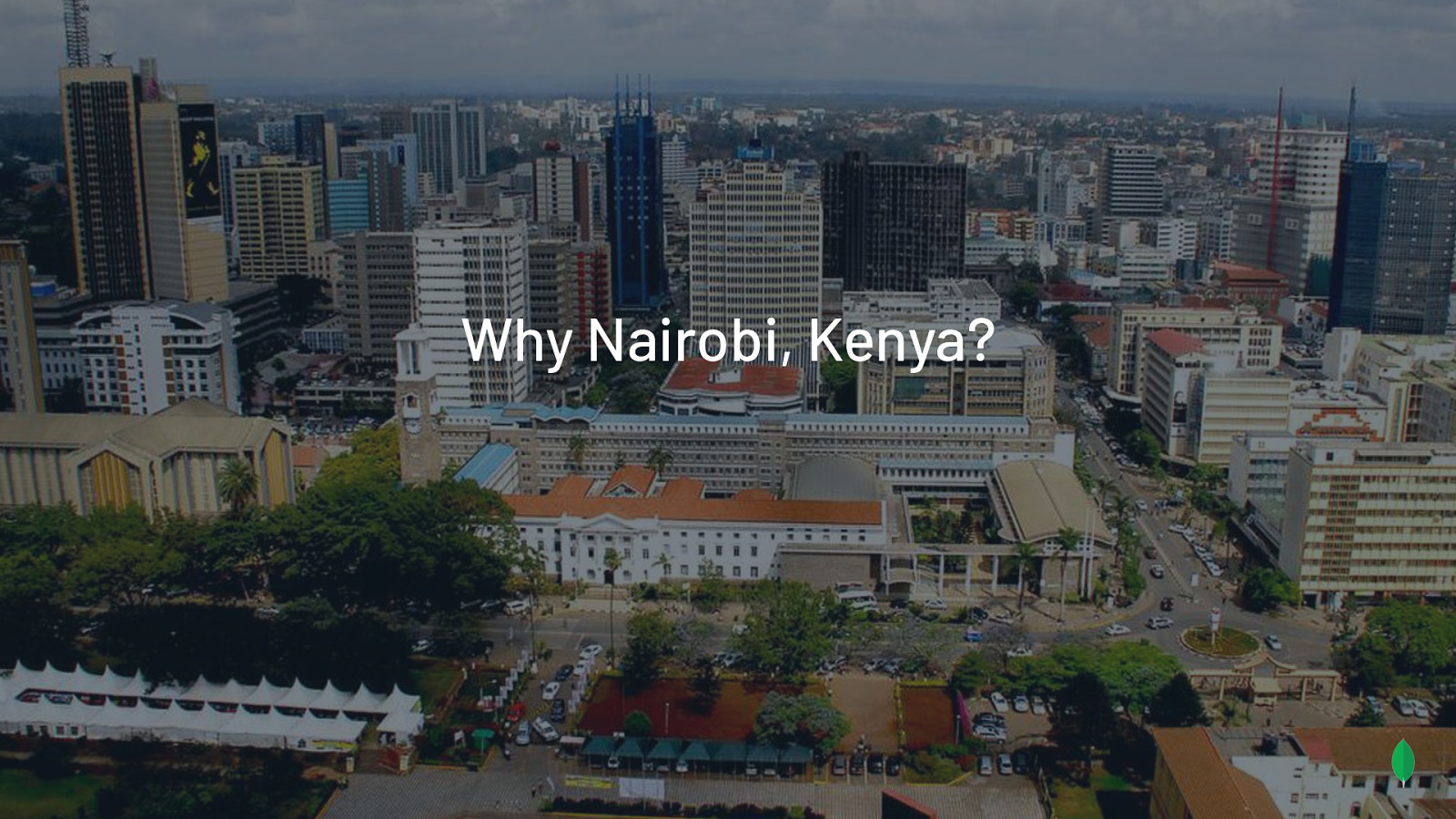

Why did we choose Nairobi?

We worked mainly in Informal Settlements like Kibera and Kayole. Where people experience many crisises.

Crowded housing often leads to fires spreading quickly with outdoor cooking.

There is also historical political and tribal based conflicts that still play out in complex ways today that many wish to find peaceful alternatives too.

I want to help other like me or who went through what I went through too.

Multiple different intersections of affinitys. Mum + baby group born in December 2018

Relying on tone, language. << Bias on dress, language etc.

Users asked for ‘recommendations’ for other helpers or ability to review other helpers which is where we come across a dangerous bias problem. However, users already using chat functions to discover credibility of source so how can we enable trust and community across social barriers?

When building an algorithm which looks to serve humans it’s tempting to think of all the ‘logical’ reasons that people might want a machine to do for them. Distance, location, demographics, skill match etc. but as we learned through our work people wanted to be matched base on how likely they are to build a bond with that person.

Eriol Fox | Design for Crisis | Ushahidi | Third Sector Design | @erioldoesdesign