A presentation at The Lead Developer in June 2018 in London, UK by Jenny Duckett

We all work in teams.

Think about the best experience you’ve had of working with a team.

What did that feel like, what was great about it, what made you excited to go to work?

And... how long did that last? How did that experience come to an end? What changed? (or maybe you’re still there…)

For me, my best experience of working with a team wasn’t an easy one.

We went through a whole load of potentially very disruptive changes during the 18 months when I was tech lead on that team - I’ll tell you about just a few of them:

That might sound like an unusual pick for my best team experience given all those hard changes we had to deal with, but despite - and in some cases because of - all those things, my team learned to take ownership of their work, support and help each other learn, spread their wings, and deliver some great things in the process.

I learned a huge amount from watching my team do that and supporting them through it, and I’d like to share some of that with you today.

But I’ve seen lots of teams who were thrown by their context changing, or by people moving around, or by different demands being placed on them.

And in those situations they found it hard to continue the good practices they’d developed in their teams.

So first of all I’ll discuss a few of those disruptions and what their effects can be on teams.

Then the main part of my talk is taking you through some things that you can do as a team lead to prepare your team to handle those transitions better.

And then finally I’ll come back to what that looks like for your organisation as a whole.

What can disrupt your team? What kind of issues am I talking about?

I’d like to be clear at the start that change is often positive! It gives us opportunities and variety in our work, and we frequently make deliberate changes in how we’re working in our teams and what work we’re doing.

The kinds of changes that I’m talking about today are generally ones that you and your team aren’t fully in control of - you might be able to influence them to some extent, but often they come from decisions that are made with not just your team in mind.

They may be positive in the long run, but at the time they can feel like a distraction to your team, and they can unsettle people.

There’s almost always some uncertainty involved - which might get resolved quickly or it could go on for months.

It’s really hard for organisations to handle these situations well, and despite best intentions from everyone involved, people often still end up feeling unheard and unvalued, or they aren’t sure where they fit any more.

So I’m going to go to some dark places here - but stick with me, there is hope :)

One of the things that’s likely to change most often in your team is people moving around - they leave the organisation, or move to another team, and new people come in and join your team.

Often those are positive changes, but they can still be a challenge to deal with for the team.

And of course team dynamics, and the balance of personalities and opinions and skills changes whenever the team members change, and taking account of that involves deliberate effort from everyone.

Maybe the senior people who your team reports to change, or their responsibilities are reorganised

The impact of that may take some time to work out or to be communicated out to everyone, and it can be hard for teams to make decisions and plan their roadmaps while those things are unclear.

As a team lead you may need to devote some time to forming relationships with your new stakeholders.

They may want you to revisit decisions you thought you’d settled, and rejustify the team’s future work and even its entire existence - and that uncertainty makes it hard for your team to continue to make progress.

The overall strategy of your organisation can change to some extent, which may mean that the focus of your team’s work shifts a little bit, or it may need to change completely.

In this situation people often feel frustrated and disempowered.

They may have little understanding of the new thing they’re meant to be working on, so they find it really hard to get going. And why should they make the effort, when it might all change again without warning?

Or, most drastically, your team could be disbanded altogether, and people reallocated to other teams or maybe even let go.

Again, this often makes people feel that they aren’t valued - as individuals, as a team, and for the work they’ve done together.

This experience is one of the things that makes good people who still have a lot to offer leave organisations.

If you’re putting people through this experience more than very occasionally and not handling these situations brilliantly, then you have a retention problem - it doesn’t matter how great you are at hiring, your organisation isn’t going to be sustainable.

But it’s not only about those dramatic changes.

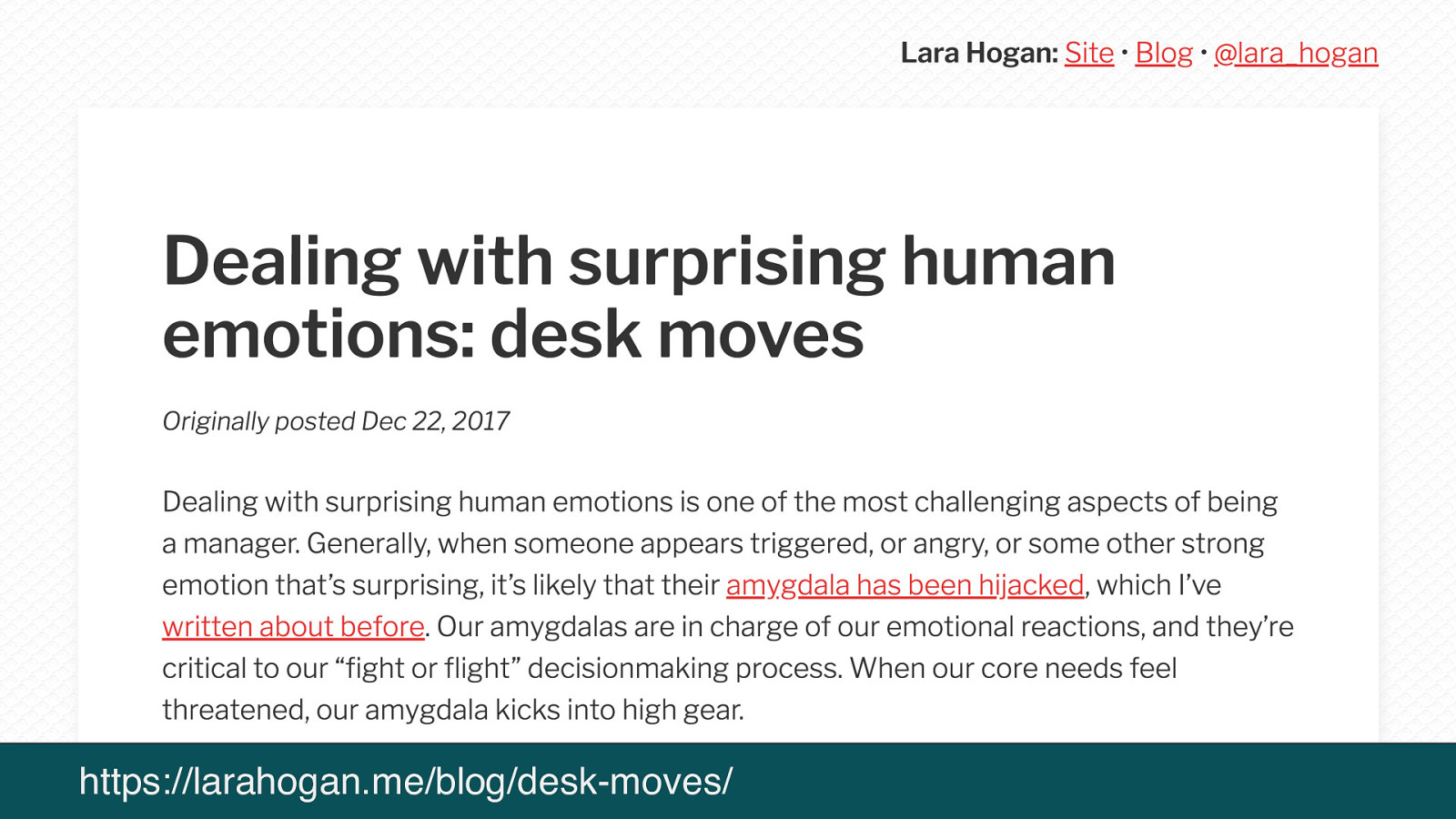

The brilliant Lara Hogan wrote a great blog post about how desk moves can threaten people’s core needs - a change that you might perceive to be relatively trivial can have a significant impact on how people feel about their work.

I’ve been through all of these things repeatedly in my career - I’m guessing you have too.

For me lots of them were really stressful experiences, and I remember vividly how I felt during the toughest ones.

The way that changes make people feel is at least as important as the fact of the change itself - so recognising those emotions and their effects is critical to helping your team continue to work effectively around these kinds of disruptions.

Everything I’m talking about today comes from a desire to support teams through these changes, by helping people feel heard, and valued, and that they have the skills and the power to make things better.

How can you support people like this?

If you’re leading a team at the moment, I’ll help you cultivate some practices in your team and in yourself which will help you manage the impact of those inevitable disruptions, and work in ways which you can sustain through them to help your team adapt and move forward - and those practices will also help your team function better even when things are a bit more stable.

And if you’re in a more senior role in your organisation, I’d like you to consider how you can better value and support the relationships that teams have worked hard to build together, and by doing that empower your whole organisation to flourish and evolve.

I’m focusing on preparing for change rather than how to react to it in the moment, because the details are going to be different in each case.

Often you have very limited time to react and take action in those situations, while you yourself are also dealing with the emotions that come with them - so me giving a conference talk is unlikely to help you much then!

First of all, work on yourself

This is the foundation for everything else

Especially if you’re new to leading a team, it’s easy to feel that you need to be on top of everything, have all the answers, review all the pull requests, and prove that you’ve got what it takes to do everything that’s expected in that role all at once.

After a few months leading my team, I realised that no one else expected that of me - I was putting that pressure on myself, and it wasn’t realistic or practicable to do all those things myself.

By trying to be involved in everything that the team was doing, I was actually acting as a gatekeeper - a blocker to the team being able to make their own decisions and take ownership of their work.

And sometimes it was inhibiting me from delegating and sharing information, or asking for advice and support.

Instead, I learned to let go of some of those details.

You don’t have to own everything. You don’t need to have this all figured out on your own.

Instead, the single most important and powerful thing you can do for the people you lead or manage is to give them your trust - everything else flows from that.

Start out from a place of freely given trust with everyone. Assume positive intent.

This is something that’s entirely within your control - something that you need to do yourself.

People don’t have to earn your trust in the first place - you’ve hired them to do their job and you owe it to them to set them up to succeed and give them the space to do that.

So tell the people on your team that you believe in them, that they’ve got this, that you have confidence in their judgement.

Leadership can be a lonely place, especially when you need to lead your team through some difficult times. You need to know who you can turn to for support, advice, or just to listen.

Maybe that’s your manager, or another mentor, or your peers.

If you’re working with people in other roles to lead your team (such as product and delivery managers) then building strong relationships with them is really valuable for this.

One of the things I’ve found most helpful was a support group, where every couple of weeks tech leads from around the organisation would get together to share the challenges they were dealing with in their teams and help each other find ways forward, come up with things to try out or get a different perspective on the problem.

Find an approach that works for you so that you have a support network you can turn to.

These things will help you get to a place where you can lead your team more sustainably - where you can take a little step back and have a slightly longer view of the team’s direction, rather than going from one crisis straight into the next.

That means that when things change you have a little bit more space to prepare for them, and a bit more perspective on them.

And when you disagree with that change but have a responsibility to help see it through anyway, you’ll need that space to figure out how to present it to your team in a positive light so that they have the best chance of accepting it and moving forward.

When you’re trusting your team and trying to not be involved in everything yourself, you need to structure the team’s work so that it’s possible for them to take ownership of it instead.

If you possibly can, focus on one goal - it can be big and hairy, with no clear path yet to get there, but have a goal that you can articulate clearly and briefly, which your whole team is working towards.

In my team we’d spent a long time jumping between different pieces of work which were important to other people, trying to spread ourselves too thinly.

That constant balancing act meant that it was hard for the team to understand where our priorities lay, and so they couldn’t take real ownership of any of the work.

Eventually we decided that we had to stop splitting our efforts and focus the team on one goal. The effect of that decision was magical: it cleared a path for the whole team to be able to take hold of that big challenge and figure out how to solve it together.

We were really clear about what we were trying to achieve overall, and everyone in the team understood that. We agreed as a team which parts of it were essential to get done by the deadline, what else we’d like to be able to do, and where the dependencies lay between those parts.

And having that shared understanding of the scope of the problem and how we’d prioritised different parts of it meant that the whole team was empowered to make decisions constantly within that scope, to get it done. And we did!

Seeing the team take ownership of that challenge and how they all learned and grew during that time brought me a huge amount of joy and pride… How much?

Enough for me to spend a whole weekend making this cake to celebrate their awesomeness :)

Once you’ve defined your goal, communicate it often, at every meeting with other teams, with your own team, maybe even every standup - every day.

It’ll feel like you’re just repeating yourself and surely everyone is bored of hearing it over and over again, but do it anyway.

It’s always worth reassuring people that the goal hasn’t changed, or if it is evolving then the way you phrase it will bring people along and help you develop your ideas together.

You may not be able to define all of your team’s work in terms of one single goal - in my team we were still supporting all the other products that we owned around the edges of that.

But communication is even more important in this case: work out how you’re going to divide your efforts clearly, whether that’s by time, or people, or story points - then make those priorities clear to your team, and iterate them openly if you need to.

Make sure you give your team enough background on what they’re working on for them to be able to pick it up and run with it - a team with a shared understanding of a problem can make their own decisions about how to deal with the challenges they face along the way.

How might you do that?

When you’re writing up a user story or ticket for someone to work on, document the context you have on it. You could use techniques such as story kickoffs to help the team agree an approach to a problem before someone starts working on it so that they don’t get as far as opening a pull request before having that conversation. For bigger changes of direction, you may need to go further.

A few months later, our team was asked to change direction to work on a big migration project which other teams had been working on for a while.

The team were a little apprehensive about that switch - they felt they didn’t know much about the migration (other than that those teams had been finding it tough).

So I organised some workshops at the start to get the team more familiar with what the migration involved, and to help them put their bits of existing knowledge together and learn from people who had already been working on it.

That meant that the team had a shared base of knowledge before we started working on the migration properly.

Now that you’re structuring the work of the team so that it’s possible for them to take ownership of it - what does that actually look like?

My team took on 2 new junior developers just at the point when we had a big deadline a few months away, and although we were really keen to support them as well as we possibly could, we also had some concerns about the impact of that change to the team on our ability to meet that deadline.

But in fact the changes we had to make in the team in order to support them were hugely positive for all of us.

We transformed our ways of working by being more explicit about our intentions and assumptions, and making it clear that the whole team is learning together.

We achieved more than we thought was possible in an incredibly collaborative way, with the whole team able to take ownership of the problems we were grappling with and solve them proactively.

First of all, we had to become great at integrating new people into the team.

So with each new starter, we iterated and improved our onboarding process.

We’d assign someone in the team to mentor them for their first few weeks - often that was the last person who’d joined.

We made sure we had clear and up-to-date technical setup documentation.

We arranged for the new person to meet everyone on the team individually, so they had a chance to start building relationships and understand what everyone brings to the team.

And because everyone understood what our goal was, they could all answer their questions and explain what we were doing and why…

And, last but not least, we introduced them to the biscuit matrix and got them to add their favourites to it :)

This was a long-running effort to map all biscuits into a 2-dimensional space, where the axes were:

We’d had lots of new people starting, so everyone was trying to absorb context and figure out how things worked.

That made it easier for us to be aware of the importance of learning continuously, but whatever the situation in your team you can encourage that yourself as well:

Get your team into the habit of sharing knowledge about their work really frequently.

Make it possible for other people to work with confidence on whatever you’re doing - both now and in the future (and I’m including future me as a different person).

There are lots of different ways that people in the team can do this…

Writing great commit messages, detailing the why as well as the what

Adding comments on support tickets and user stories, making your progress on them visible to everyone as you go

Keeping your documentation up to date as part of every piece of work

When the team makes a decision, document the context and reasons for it - architecture decision records are great for this

Working in this way makes it much easier for new people to understand what’s going on and what’s expected of them, and to pick up the context they need to be productive.

And when people leave, it reduces the amount of information you need to download from people’s brains before they go.

I’ve often seen teams which have trouble getting things done when particular people are off sick/on holiday/in meetings all day.

If you learn to share your context frequently, you’ll be more able to keep work flowing during disruptions - treat those smaller regular disruptions as practice for bigger ones.

When my team started doing mob programming regularly, I was amazed at how rarely they were blocked on anything and how quickly the team made progress.

They were able to plan and prioritise their own work, and make decisions as a group because the people they needed were there already, with the right context.

When particular people weren’t around for whatever reason the others could carry on without them, and they developed ways of catching people up quickly when they returned…

Emma wrote a blog post about the team’s experience of mobbing - go and read that if you’d like to find out more.

This was an incredibly robust way of working for us, and we achieved more than we’d thought was possible in that time.

The team didn’t always mob on everything after that, and it doesn’t suit everyone, but knowing we had it as a tool we could use to share context, make decisions and move forward was incredibly powerful, and the team were able to use mobbing later on to tackle areas that were completely new to them much more effectively.

An empowered team who are practised at integrating new people, taking ownership of challenges together and sharing their work openly is more able to handle the impact of people moving or not being around.

When your team is asked to work on something different, people can still feel disappointed and frustrated about that decision, but if they’re used to supporting each other to learn and figuring out how to solve problems together, they’ll be in a better place to accept it and move forward constructively.

So far I’ve talked about working on yourself, and things you can do to help the whole team function better together.

But a team is made up of individuals, with different needs and skills and interests.

Whether or not you’re responsible for directly managing the people in your team, supporting them individually to develop their skills is a great way of growing the capability of your team as a whole.

Look for opportunities to develop members of your team in every piece of work your team does.

Helping people grow isn’t something you fit in around the edges - it should be the default way of working, a core part of what you do.

So use the work your team is doing anyway to give people the experiences they need to become better developers and be able to take on bigger challenges in the future.

If you’re doing this as part of your team’s everyday work, then it’s easier to continue doing it during times of uncertainty.

You may be under pressure to reduce the amount of time your team spend on their learning and development when things are hard, but if it’s built into the way your team gets work done then you’re not relying on people taking time out in order to learn.

Even though I wasn’t managing the people on my team directly (they had other managers elsewhere), I still had regular catchups with the developers to keep in touch with how they were feeling about the team and what else was going on for them.

And I discussed their individual goals with them and their line managers. From those chats, I had a good picture of the opportunities different people on my team needed - so I could make sure they got to work on stories in an area they wanted to learn more about, or ask them to lead on particular projects.

I found it incredibly rewarding seeing people in my team take on these challenges and succeed at things they weren’t sure they could do beforehand.

When you want someone to lead on a piece of work, you need to be able to delegate it effectively to them:

As well as giving people specific opportunities like this, show them more generally how the team works and what’s involved in keeping it running smoothly over a longer period of time.

When I had pre-planning meetings with the PM and DM early on in the team, we started bringing other members of the team into those sessions to help them get a fuller perspective on how the team worked:

That experience prepared them for taking on leadership roles themselves.

Supporting individuals to develop like this is about growing the next generation of leaders so that the organisation can grow sustainably.

It’s easier and more inclusive to be able to hire less experienced people and give them opportunities to develop over time, rather than only hiring people who already have all the skills you need.

Aim to make yourself dispensable eventually - both as a leader and as a member of the team.

Prepare the team for you moving on, even before you know it’s going to happen - know who you could hand over to as team lead, and help them be ready to step up when you need to move on, and reduce the disruption to the team.

When I came back from a couple of weeks’ holiday and found that my team had carried on as normal without me, had felt able to make decisions on everything that came up and taken it all in their stride - then I knew that they didn’t really need me any more.

And that came with a little bit of sadness, and a lot of pride in them.

People who have experience of leading work themselves, and who are used to thinking about how to make teams and processes work better, are really well-placed to shape and lead new teams if they’re restructured, or to contribute effectively to other teams if they need to move.

An organisation that gives its people opportunities to grow is more able to retain them and benefit from their domain experience and skills for longer, helping the organisation be resilient and move forward with an understanding of where it’s been already.

Look outside your team as well.

Show your team where they fit into the wider organisation and how they relate to its goals.

You probably have a wider view of the organisation than your team does.

Use that context to help people forge links across team boundaries.

When you hear about another team's plans which are relevant to what your team are doing, pass that information on and get people from the team to start a conversation with them.

Or if you know someone else was working on a similar problem a while ago, ask them to come and talk to your team about their approach.

And conversely, help other teams understand what you’re doing and why it’s important.

Encourage your team to talk and write about their work - to show it off and be proud of it!

Whenever you can, give those opportunities to speak to people who could benefit from that experience - not only to practise public speaking, but also to help them cultivate that wider perspective on your team’s work that they need in order to communicate it effectively to people who aren’t familiar with it yet.

Relate your team's goals back to the wider organisation goals frequently.

Show your team where they fit in the bigger mission, and how other teams are working towards the same goal, and why it’s valuable.

One of the challenges we were facing as an organisation at the time was how to properly support all the many products we’d built, and we were defining technical standards with the aim of making our applications more consistent and easier for us to understand.

I’d often refer to that wider challenge in team discussions, as a guiding principle - so the team could make decisions in their day-to-day work which were consistent with those wider goals.

And knowing about that push enabled the team to find opportunities for contributing to the standards and working with other teams on them.

There is some value in shielding your team from all the other big questions and uncertainty flying around the organisation so that they can focus on your team’s goal, but over time I think it’s more effective to share some of that context with your team.

If your team is completely sheltered from all of those potential distractions or other priorities, they might get more done in the short term but when one of those things gets through your shield it’ll come as more of a shock to them, a bigger disruption.

And that isolation means they’ll be less prepared to work on something else if they need to.

So mention some of these things to your team occasionally - they might have heard rumours already and it’s better to be able to discuss them openly.

Tell them what you’re doing to handle the situation if it might affect your team.

And tell people sometimes when you’ve said no to someone who wants the team to take on other work - it’s an opportunity to show why the thing you are doing is important and valuable and worth prioritising over other things.

A team who understand how their work relates to other teams and how it contributes to a bigger goal are more likely to be able to accept changes in direction which mean they need to work on something different.

They’ll be able to see how it’s all related - maybe it’s not such a big change after all.

If they know what other teams are working on and why, and already have good relationships with them, they’ll be more able to contribute usefully if they need to move team.

An organisation made up of these supportive networks is much more able to learn from its mistakes than one where teams are siloed, and its ability to re-form itself around new challenges makes it more resilient and sustainable.

I’ve talked about all these things you can do to prepare yourself and your team to handle changes of various kinds.

But you also have the opportunity to try to influence how change comes about, and to some extent when and how it impacts your team - you can be an active participant in that process rather than waiting for it to happen to you.

Make sure that your manager, and other people who are in a position to make these bigger decisions, understand how much work it takes from everyone to build a team that works well, and the time it takes for people to become familiar with the domain they’re working in.

Understand and communicate to those people what the impact of changing the direction of your team would be - what kinds of changes do you think your team could handle at the moment, and what might be possible in the next few months?

Talk those options through with them.

These techniques that I’ve talked about will help your team continue to be happy and productive in the face of disruptions, but teams are never infinitely flexible.

I’ve frequently had to argue for not restructuring teams wholesale, but I’ve also been able to agree ways to shift my team’s direction to meet bigger goals while bringing the team along on that journey.

Help the people above you understand what you need from them in order to build a sustainable team:

You and your team need their trust.

Teams need to know that they have a mandate and the space to solve the problems they come up against.

The higher up the organisation this comes from, the better.

People at the top can’t create a culture of trust alone, but they can reinforce it or destroy it.

Explain the value of the work your team members are doing outside your team’s core mission to the people above you.

Give them concrete examples of…

Ask for their support in finding space for that work, and defending its value if that’s necessary.

Communication around wider changes is absolutely critical.

When more senior people are considering making changes that would directly affect your team, they should discuss it with you first.

Hopefully you’ll be able to shape that direction together, drawing from the more detailed context you have on your team as well as their wider strategic view to find a good way forwards for everyone.

Or at the very least you can try to ensure the decision is communicated to your team with empathy.

Anticipate the questions your team will have, and make sure that there’s some kind of answer (even if it’s just “we don’t know yet, but we’ll work it out together”)

What does this all look like for your team and your organisation?

A team who share their knowledge openly and collaborate constantly can handle people leaving the team, and are in a great position to support new people who join.

A team who see new challenges as opportunities for learning together and are trusted and empowered to take ownership of problems can embrace new challenges, and can make progress during times of uncertainty.

A team who understand how they're contributing to the organisation's goals and where they fit in the overall strategy, can more easily accept changing the focus of their work to support that goal in a different way.

People who have experience of defining problems and leading work, and have seen what's involved in helping a team run smoothly over time, are ready to lead new teams and contribute effectively when they move.

Senior leaders who understand the effort involved from everyone in building a team like this can make more informed decisions about changing the direction of the organisation.

An organisation which supports everyone to learn and develop all their skills, and values and nurtures communities, is more capable of growing and changing direction sustainably.

Maybe this all sounds too idealistic, or impossible to achieve.

It does take work from everyone to start working in this way, and continuing takes deliberate effort and attention too.

Even if you’re working well together during normal times, when stressful things happen it’s easy for a team to default back to not pairing or communicating.

It can be hard to prioritise learning or empowering people when you’re under pressure and you don’t know what the future holds.

But that’s when these things are even more important - they will see your team through the tough times if you hold onto them.

Embedding these practices now and committing to them will enable your team to adapt to change together.

Finally, thanks and love to my wonderful old team (this is just a few of them), who managed to do all this and more, and who taught me so much :)