Web3: Creating problems where we need solutions

Laura Kalbag: laurakalbag.comsmall-tech.org

Hello, my name is Laura Kalbag and I’m a sucker for punishment so I’m going to talk about Web3, - and how it really creates problems where we need solutions.

A presentation at Smashing Meets For Good: Ethics in the digital world in February 2022 in by Laura Kalbag

Laura Kalbag: laurakalbag.comsmall-tech.org

Hello, my name is Laura Kalbag and I’m a sucker for punishment so I’m going to talk about Web3, - and how it really creates problems where we need solutions.

Web3 is apparently the next significant era of the web.

Web 2.0 is our current era, typified by social networks and big platforms populated by user-generated content. It’s the era of Facebook, YouTube, Flickr… apps on the web rather than the desktop. The term “Web 2.0” implied the existence of Web 1.0.

The web before Web 2.0 was essentially static websites with not much dynamic functionality. Web 1.0 was publishing personal sites in webring communities, as people learned about the potential of the web.

Web3 was coined and stylised in 2014 by Gavin Wood, co-founder of the second-most popular cryptocurrency, Ethereum. (I’m going to come back to Gavin later.)

The Web 1.0 era probably spanned around 15 years, from the popularisation of the web until Web 2.0 became the next big thing. It’s been about 20 years since Web 2.0 became cool, so maybe we are due another era. But is it that next era this Web3?

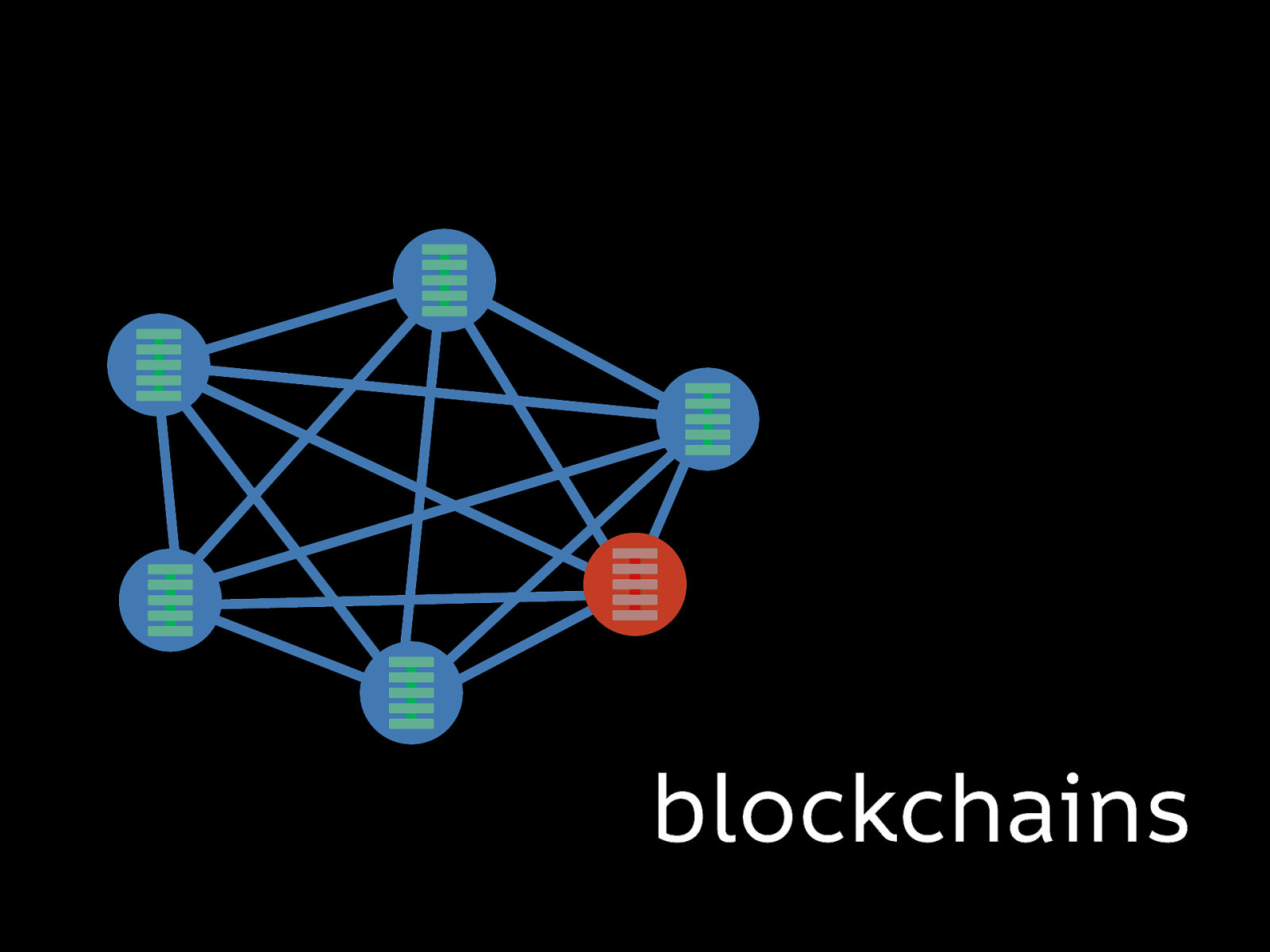

Web3 is founded on the idea of decentralisation based on blockchains. Web 2.0 is classic centralisation.

Big Tech platforms that want you to join them, create content for them and keep consuming other people’s content within their walls. Many of these platforms are free—who’s going to pay to socialise online? And so Web 2.0’s tycoons monetise data, specifically the information of the people who use their platforms, through profiling, advertising, and generally getting a cut when they encourage you to buy more stuff. And we’re stuck using them because centralisation means that - most of our friends, employers, and even government services use these platforms.

Centralisation also means that all of this valuable personal information is kept in a central database. This means there’s one place you need to access (or hack) if you want the passwords that people reuse, their credit card information, or their activities they’d rather keep to themselves.

And centralisation means you don’t have much say in how these platforms that consume your lives are run. You’re just a user. You’re usually not even a customer. You’re stuck with what you’ve got.

So if you’re looking to solve the problem of centralisation…

…you look to decentralisation. Decentralisation essentially means distributing something across many locations rather than concentrating it in one place.

Alternative forms of decentralisation exist… but the Web3 movement has chosen blockchains.

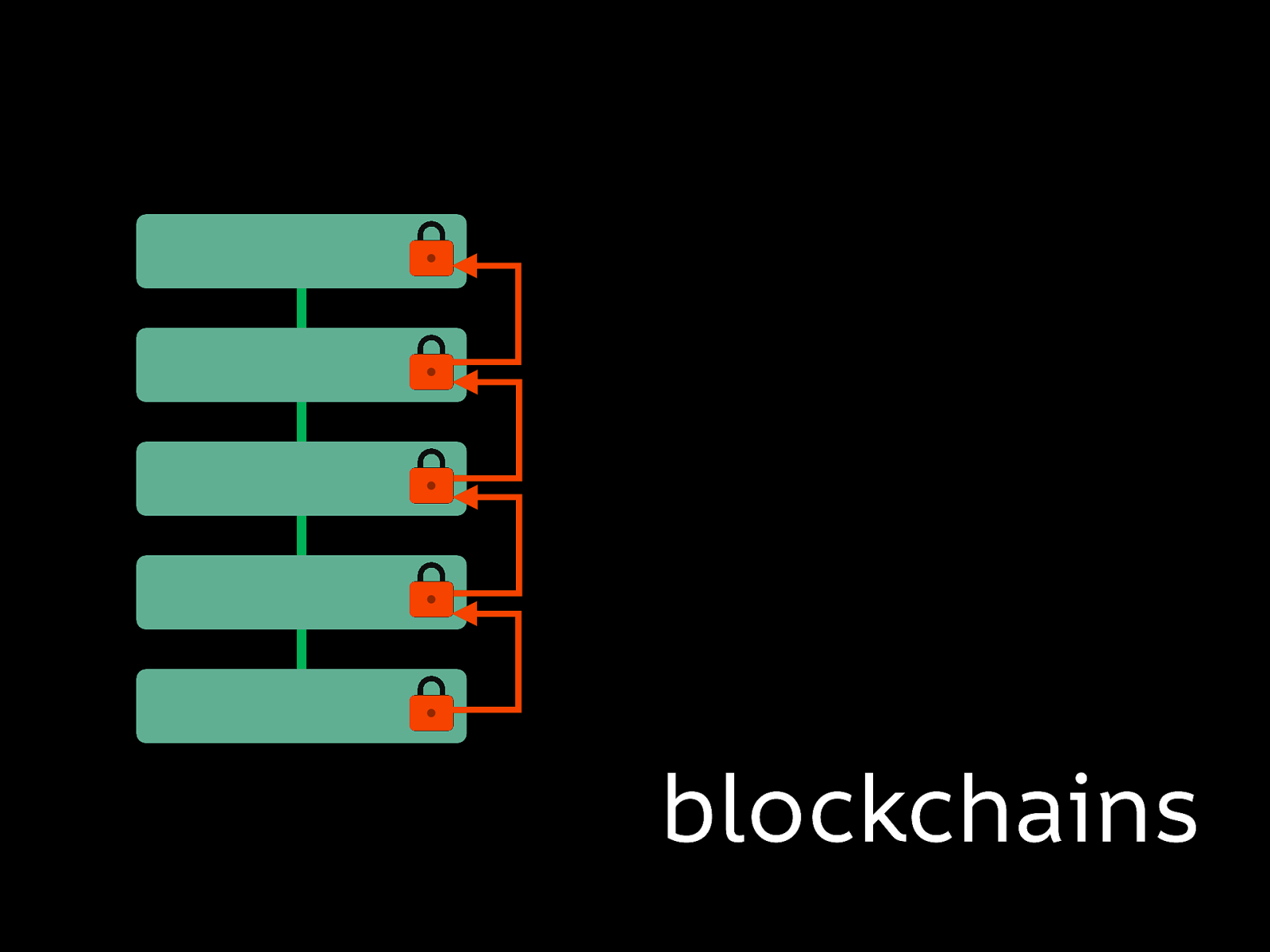

A blockchain is a chain, or list or ledger, of transactions that cannot be edited. Each transaction has its transaction data, a timestamp, and is cryptographically signed with a hash of the previous transaction. The hash means you can’t change the list of transactions without anybody noticing.

The unchangeable nature of blockchains makes them useful for the exchange of currency. Relying on the chain’s history, you can be assured that the person spending the currency is the person that rightfully owns that currency.

These currencies are called cryptocurrencies because they are built on cryptographically-secured ledgers, pretty much always blockchains.

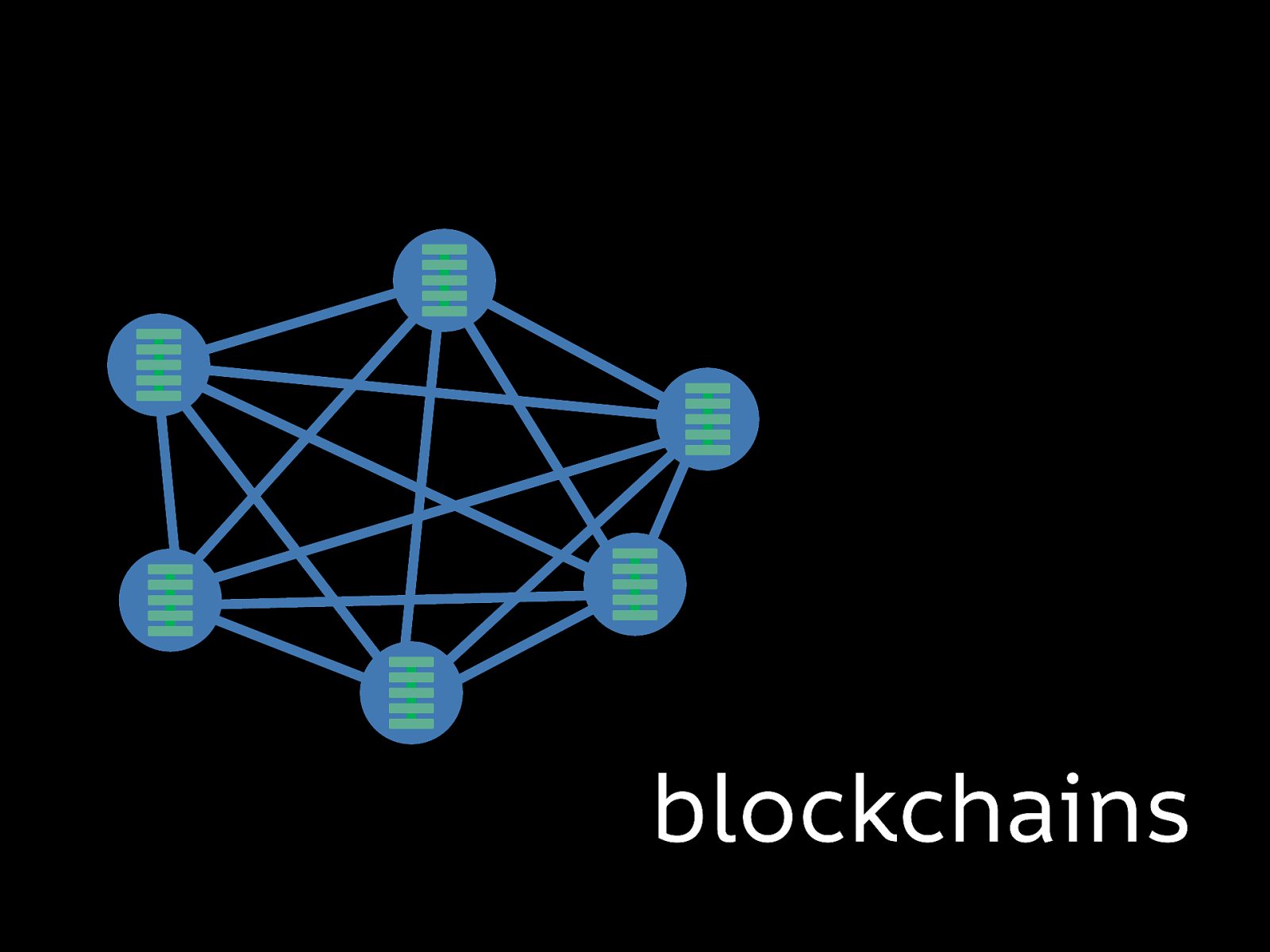

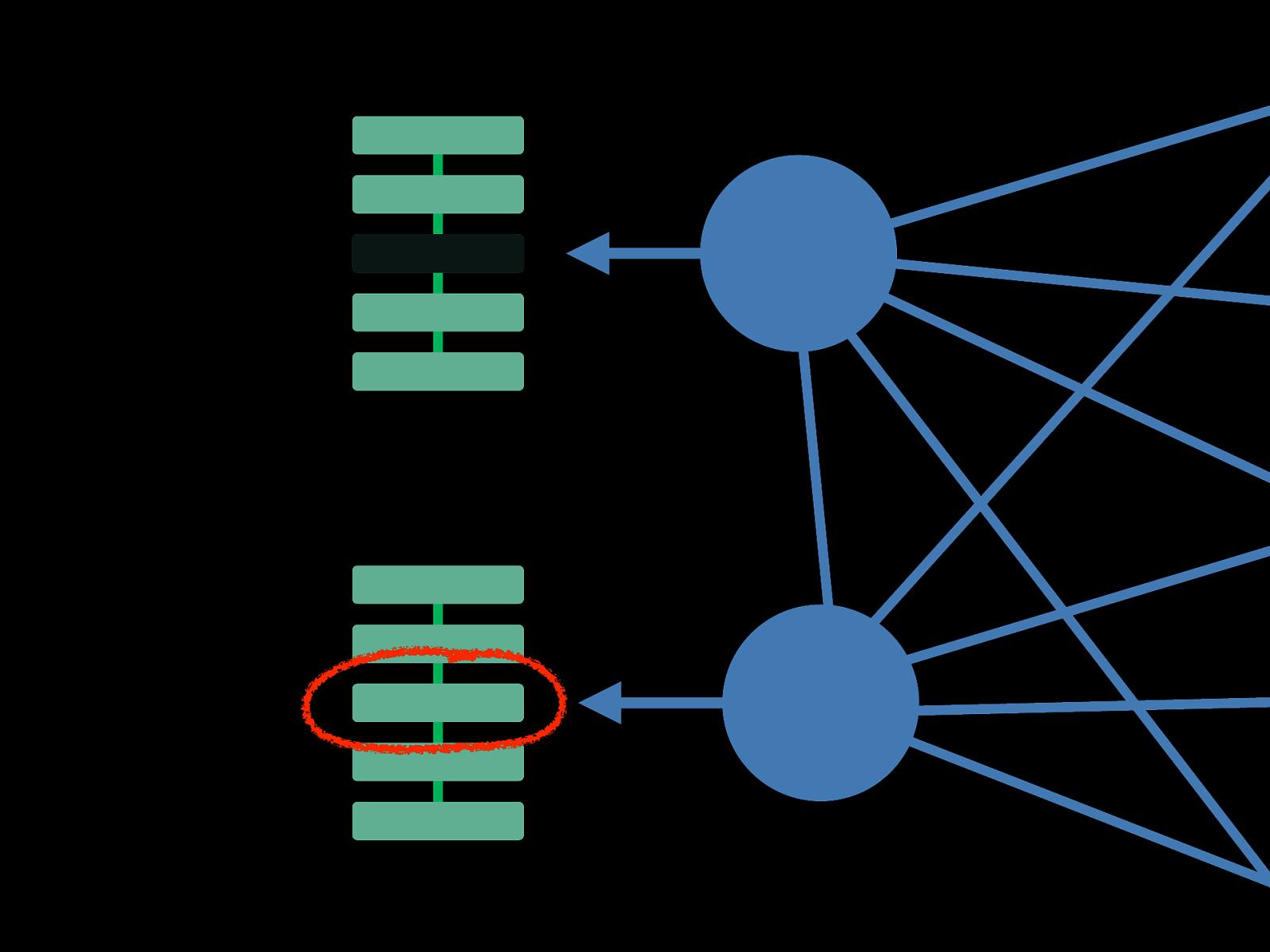

Any computer can have a copy of a blockchain, which means anyone can keep track of these types of transactions.

Many copies can exist in different locations across a network. This is what makes blockchains decentralised.

If one copy is corrupted, lost or inaccessible, it doesn’t mean all the other copies are corrupted. If something happens to one of the copies of that blockchain, another copy can be used to verify transactions.

The blockchain’s security increases as more machines on the network exist to verify the validity of the transactions.

Inversely, if there aren’t many machines on the network and somebody can control 51% or more of the processing power on the network, they could validate a corrupted transaction.

As the transactions are visible to every copy of a blockchain, all blockchain transactions are public The transparent nature of these transactions is why blockchains are considered verifiable and beneficial compared to opaque systems vulnerable to corruption.

One such use of blockchains is in supply chains, where any interested party could gain insight into the origin and history of a product. I’ll come back to the transparency of blockchains later.

When something is built using a blockchain, it is referred to as being built “on the blockchain.” This terminology is confusing because it implies there’s only one blockchain, and everything built on the blockchain is built on that one blockchain. Which, of course, would be a form of centralisation, one central blockchain.

Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, the original use and currency of blockchain technology, are considered a way to avoid the centralised intermediary institutions of banks. The critical difference between a cryptocurrency and a conventional currency is that a cryptocurrency is “trustless”.

Cryptocurrencies don’t just exclude traditional banks but financial intermediaries like Stripe and Paypal. Centralised banks and financial intermediaries are considered a problem because they create barriers between you and your currency, with inefficient transfers, identity verification and regulation.

These issues of verification, identity and anti-regulation are crucial principles in the Web3 community, which is why cryptocurrencies and Web3 are popular amongst those with libertarian beliefs.

The problem these communities have with regulation is that the regulation of technology, in particular, is slow, imperfect and limited by the funds provided to their bodies by governments. And the “revolving door” between industry and regulation where those who work in one seamlessly move to the next. Along with their vested interests and biases. I totally agree that these are problems with regulation, especially when wielded by governments hostile to their populations.

On the other hand, regulations such as the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation), whilst often abused and deliberately misinterpreted, provide some semblance of protection for everyday people using technology. For example, the GDPR limits the personal data about a person that can be collected without their consent.

Cryptocurrencies are actually regulated to some degree. Many governments either recognise them as currencies or treat them as commodities. While existing regulation is pretty patchy, as it is with much of the tech industry, regulation is inevitable, particularly in areas that governments suspect of money laundering or funding terrorism. And much of the activity around cryptocurrencies is likely to be protected under consumer rights.

Which is important because cryptocurrencies are rife with scams known as “rug-pulls,” where the developer abandons their project, often making off with all the raised investment when its value is at its highest. It’s understandably difficult to know who to trust in a space that thrives on the trustless, permissionless and anonymous, with little oversight.

Especially when a high-value project might be a telltale sign that somebody is about to pull the rug out from under you.

Regulation alone is not enough; it’s often hard to enforce, especially inside the mass of the web.

And that really is where we need to talk about standards and ethics. As people who use the web to build products and services for others, we need to take responsibility for the impact of our work.

Cryptocurrencies are not an optional extra in Web3; they are the entire economic underpinning. You’ll find this referred to as a “token economy” or “crypto-economic protocol.” These terms might sound fancy but are basically using tokens, usually in the form of cryptocurrencies, as a financial incentive for developing and maintaining and participating in Web3 organisations or apps. You can offer up your machine to use as a server and get tokens in exchange.

These tokens can operate like shares, increasing a person’s ownership stake in an organisation or app and giving them a more significant say in its direction. Because tokens are stored on the blockchain and ownership cannot be transferred without the owner’s permission, nobody can take your tokens away from you.

Web3 devotees cite the token economy as uniquely democratic and egalitarian.

Reddit is already using tokens for its Community Points cryptocurrency built on Ethereum. Subreddits (Reddit subforums) can create tokens to reward their participants based on how many upvotes their posts get from their subreddit community.

Reddit was already encouraging involvement through upvotes, so using tokens as a financial incentive to participate and produce content benefits their business by attracting new users.

Though Reddit, being a centralised platform with a board of directors and owned by Condé Nast, is hardly part of the Web3 decentralisation dream.

The Web3 token economy focuses on the organisational structure of DAOs (Decentralised Autonomous Organisations) running decentralised apps, or dApps.

The concept of a DAO was developed by Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin. DAOs are organisations that anybody that theoretically join, with a flat hierarchy where tokens are used for governance, to vote on decisions for the organisation and influence its direction.

Each DAO can have different structures and rules for how it operates, and these rules are hosted on the blockchain and called a “smart contract.”

You could liken a DAO to a company run entirely by shareholders, except that it is not a legally-recognised company. And DAOs are currently primarily used more for projects than companies, perhaps similar to an Open Collective.

Web3 fans wax lyrical about DAOs being the most democratic way to run communities and organisations.

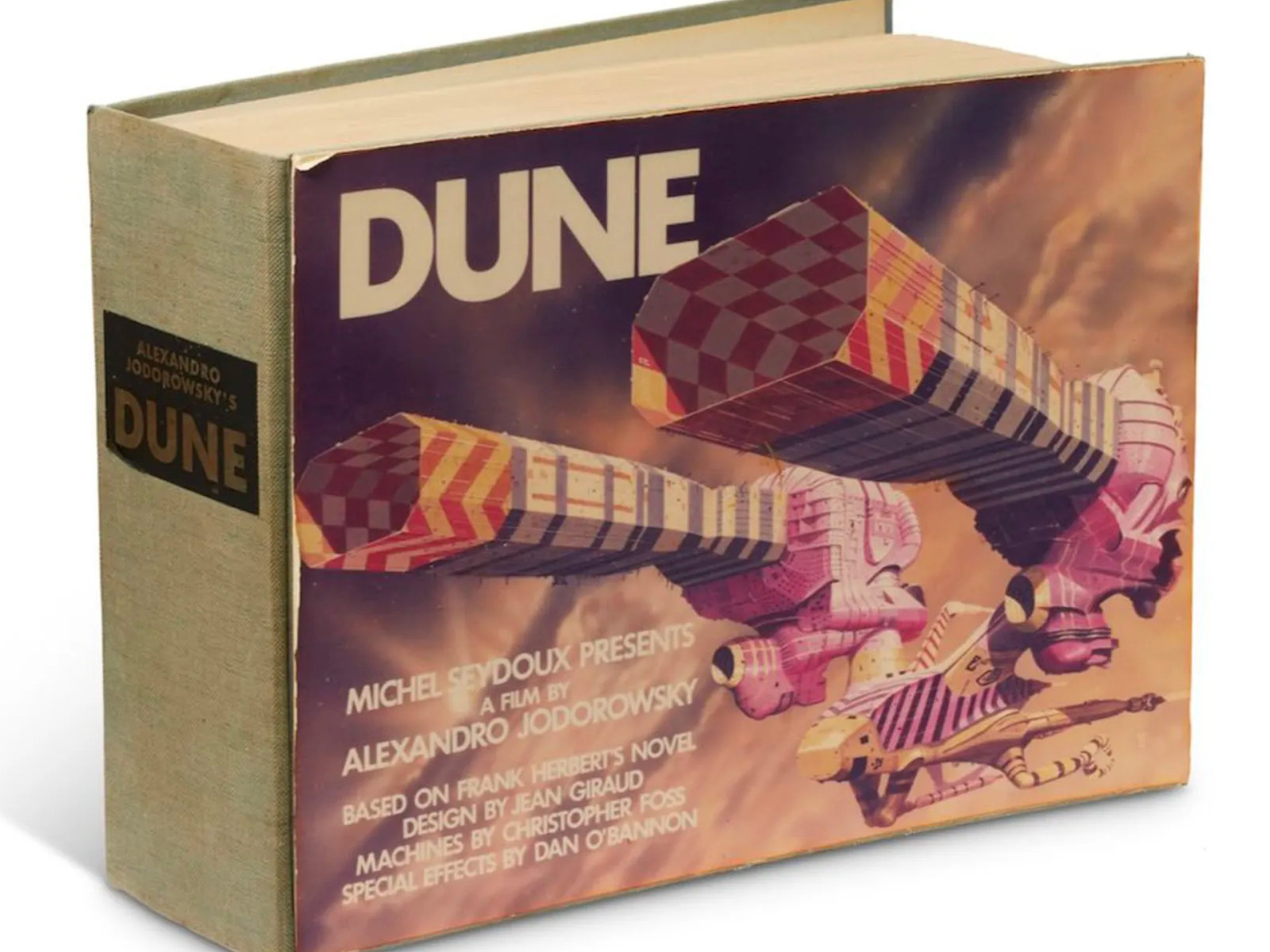

Take TheSpiceDAO, which was set up so its members could collectively bid on a rare copy of director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s book detailing his plans for a film based on the book Dune. (The film project was abandoned)

They won the auction and celebrated with this tweet:

We won the auction for €2.66M. Now our mission is to:

Make the book public (to the extent permitted by law)

Produce an original animated limited series inspired by the book and sell it to a streaming service

Support derivative projects from the community

The members of TheSpiceDAO failed to realise that buying a copy of a book does not give you the rights to that book, the script or any other intellectual property it contains. Even if it was a very expensive book.

TheSpiceDAO’s mistakes are not inherent to DAOs in general. Still, the story is one of many exemplifying the naïvety of many involved in the movement. They seemingly don’t understand that Web3 doesn’t mean that your communities and technologies are operating outside of regulation and law like some kind of digital international waters. Especially when you’re interacting with existing established structures.

And are DAOs really that different from existing established structures anyway?

When a DAO is set up, its founding members creating the smart contract can reserve privileges for themselves, usually in the form of additional tokens. And those with the most tokens have the most power to shape the direction of the DAO, becoming de-facto leaders and continuing, as many systems before it, to encourage centralisation of power.

As my partner at Small Technology Foundation, Aral Balkan, says of decentralisation: “it’s not decentralisation unless you decentre yourself.”

dApps are apps that run on the blockchain. As with any other app ecosystem, they could be any kind of app, but their purported benefit is that dApps are decentralised. The app and all its data are stored on each of its users’ machines. As with other blockchain technologies, their decentralisation and security rely on the participation of many users. If enough users are using the dApp, it should have no downtime because another copy will be available if one goes offline. Another suggested benefit of dApps is that their decentralisation is censorship-resistant, so governments and other authorities cannot monitor or control the activity of their users.

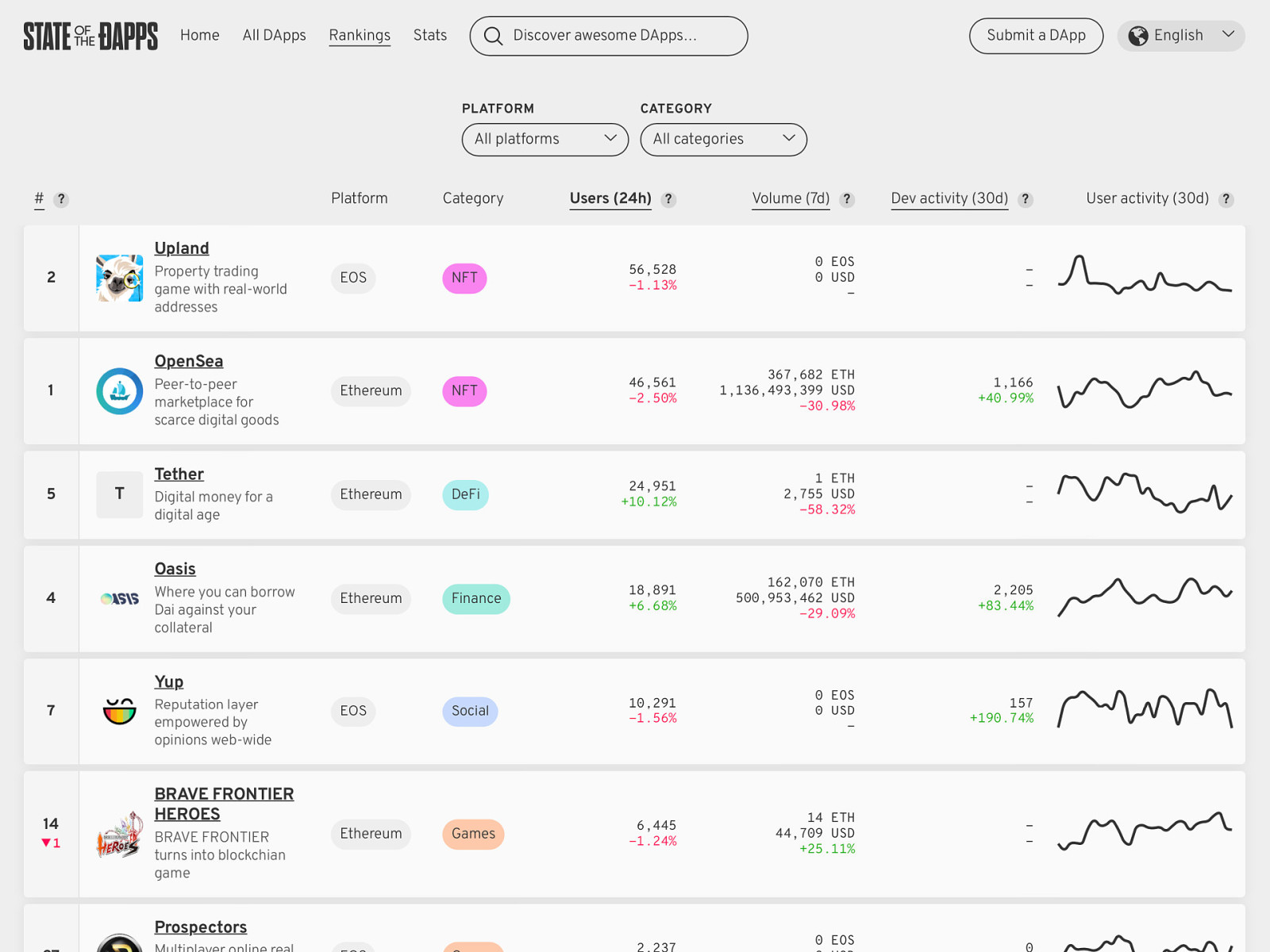

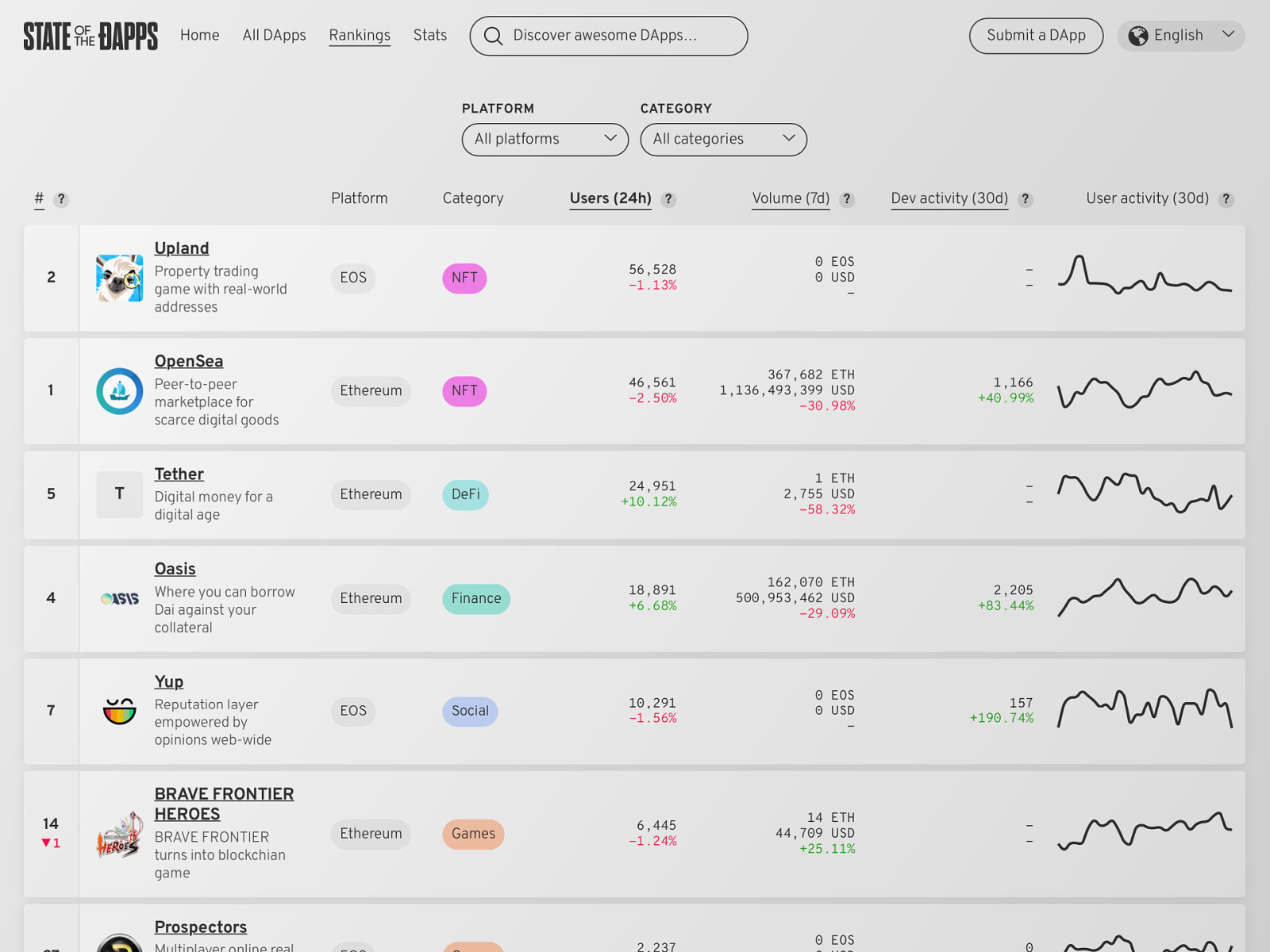

dApps are currently mostly cryptocurrency exchanges, cryptocurrency services, games to earn cryptocurrency, apps to gamble cryptocurrency and NFTs.

If the current marketplace of dApps were compared to a shopping mall, it would be a mall full of banks, bureau de changes, betting shops and gambling arcades. What a delightful vision of the future.

My shopping mall comparison might be jest, but the driving forces behind the systems we build are consequential. Would the web exist as it does today if it weren’t for people sharing their knowledge and skills without a guarantee of financial reward?

What happens when the apps we build are designed to generate as much currency as possible? How has the collection of data affected the apps we’ve built under Web 2.0? How does that affect the character of what we make? How does it shape the experiences we create for its users?

Arguably, the overall economic system we currently exist within, capitalism, is focused on financial reward as an incentive, so it’s not surprising that Web3 continues along this path.

Regardless of the economic systems, there is a substantial environmental issue with cryptocurrencies that is unsolved and impacting our planet at an extraordinary rate.

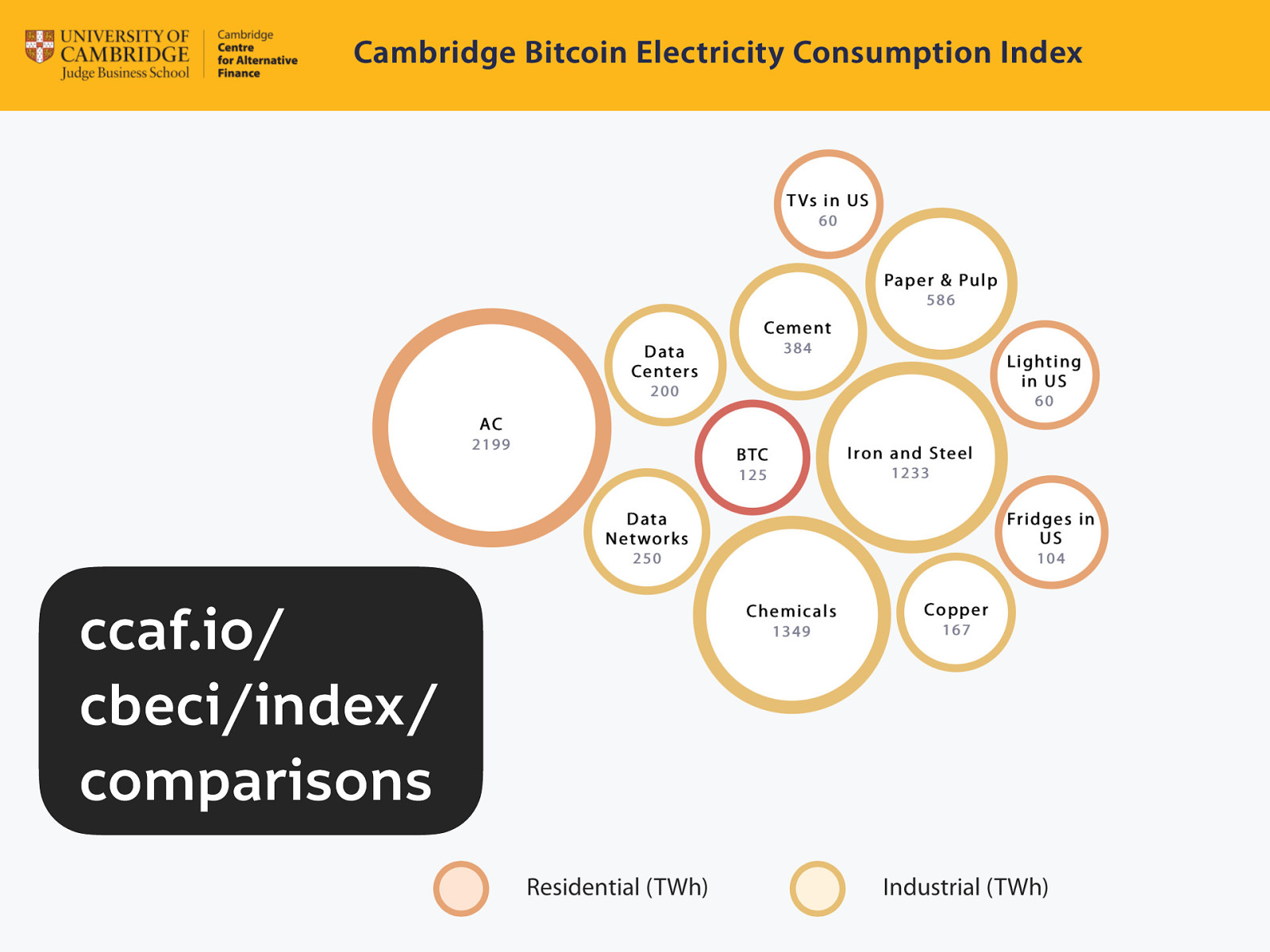

Our digital networked technology in itself isn’t wonderful for the environment.

In fact, data centres and data networks combined - consume more energy than the cement industry, the copper industry, - and almost as much as the paper and pulp industry. - See that BTC bubble there? That’s Bitcoin

The central environmental issue with most blockchains is the mechanism used to sign the transactions cryptographically, the proof of work, the element that makes the chain secure.

Proof of work is where multiple computers compete in computational effort. The concept was designed as a security measure. It requires a certain amount of computational effort, which requires a signficant amount of energy and CPU power. This deters data manipulation because it becomes too computationally expensive to make it worthwhile.

The process of creating this proof of work is also known as “mining”, as a miner can create new transactions and thus generate cryptocurrencies.

Miners are aptly named as the creation of cryptocurrencies probably has the comparable environmental impact as some mining industries.

Not all blockchains use proof of work mechanisms; there is a mechanism called proof of stake, which requires less energy. But at the time of this talk, the use of proof of stake is minimal. The use of proof of work mechanisms in blockchains means that most are incredibly detrimental to our environment because of their energy use and resulting emissions.

The two most popular cryptocurrencies, Bitcoin and Ethereum, are each estimated to use as much energy per year as small countries’ total energy consumption. Many mines are based in China, which heavily relies on coal for energy.

Right now, cryptocurrencies are certainly increasing the rate at which our planet will become uninhabitable.

There is a theoretical argument that cryptocurrencies could be beneficial to the environment. If they used clean energy, and thus encouraged clean energy production. But cryptocurrencies already using clean energy are very hard to find.

And the hope for clean energy isn’t what’s making people invest in cryptocurrencies. People are trying to make money. The primary benefit of cryptocurrencies is if you get into a currency at an early enough stage, you will reap increased financial benefits as more people invest in the same coin. Thus increasing the value of your own investment.

Which unfortunately brings me to NFTs.

NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) are one-of-a-kind cryptocurrency tokens. An NFT can be made for anything, and its value is inherent because of its one-of-a-kind, albeit artificial, scarcity.

Their uniqueness means they are often used for virtual objects like digital artwork.

But as an owner of an NFT, you don’t actually own the image of the artwork. You don’t own its copyright. As folks familiar with the web, we know the file could easily be copied and shared anyway. NFTs for digital assets don’t include the digital assets themselves; it’s far too expensive to include an image in a blockchain transaction. The assets aren’t cryptographically-signed either… no cryptographic watermark or anything.

If you buy an NFT, you own a certificate that contains a URL to the asset. Unless you own the domain and the web hosting behind that URL, somebody else owns the asset, and you don’t have any control over the URL or your asset. Somebody else could easily change the URL, or the server could be taken down, and you’ve lost access to your asset.

In theory, NFTs could be used to financially reward digital artists who otherwise tend to struggle to make money on a web where work is so easily copied. The people who benefit from NFTs are those registering the NFTs in the first place. And often, those registering NFTs are not the artists themselves, just grifters looking to make money from somebody else’s attractive-looking image or nice-sounding song.

Last year an artist found more than 100 pieces of her art for sale on the OpenSea NFT marketplace, none of which she’d listed herself.

In case OpenSea sounds familiar… it’s one of the most popular dApps built on Ethereum

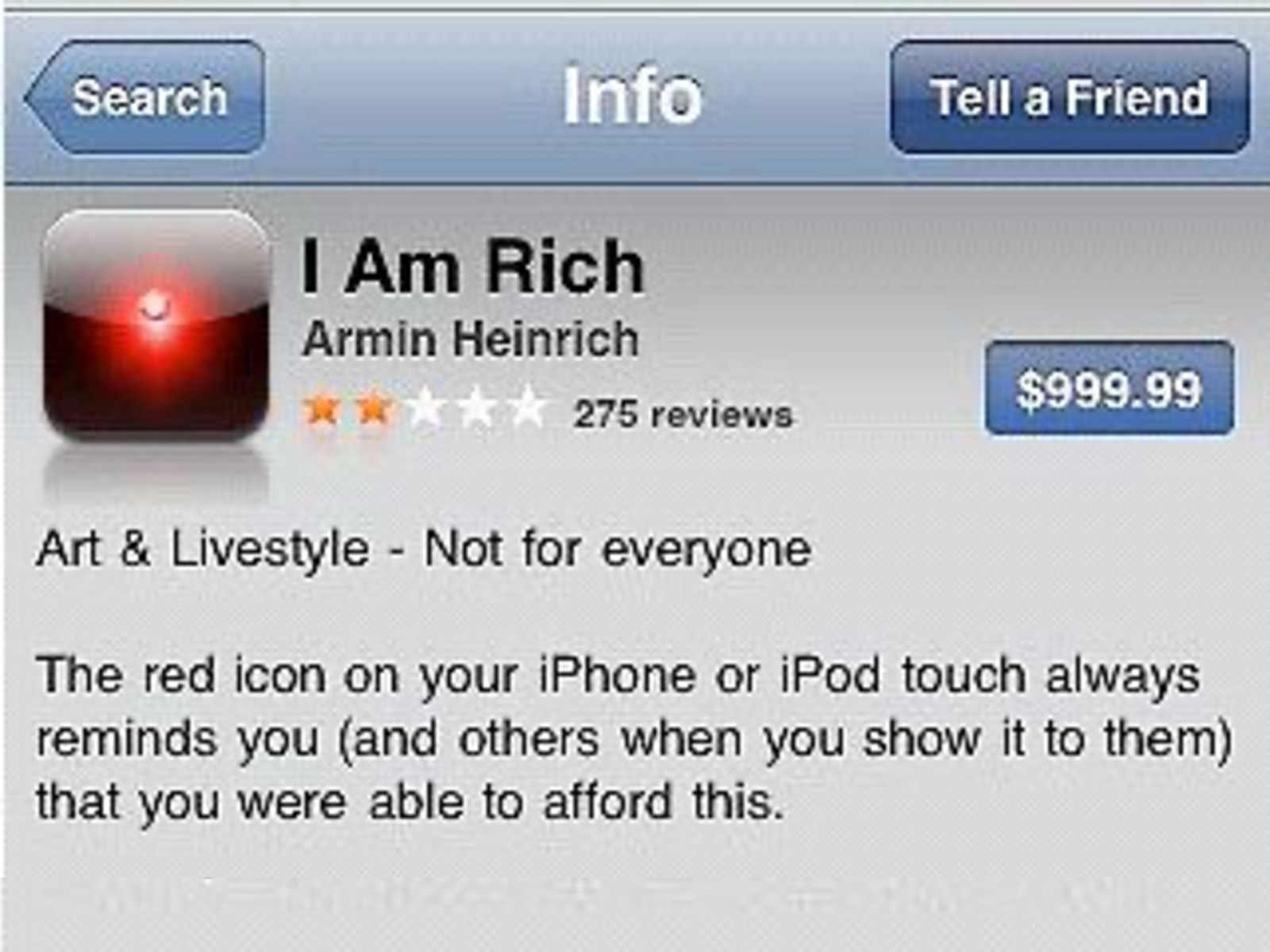

In reality, investing in an NFT is like buying the $999.99 “I am rich” app on the Apple App Store. You have paid for bragging rights and not much else. And especially while so few people understand NFTs, you might just get lucky and have someone else want to buy your bragging rights off you.

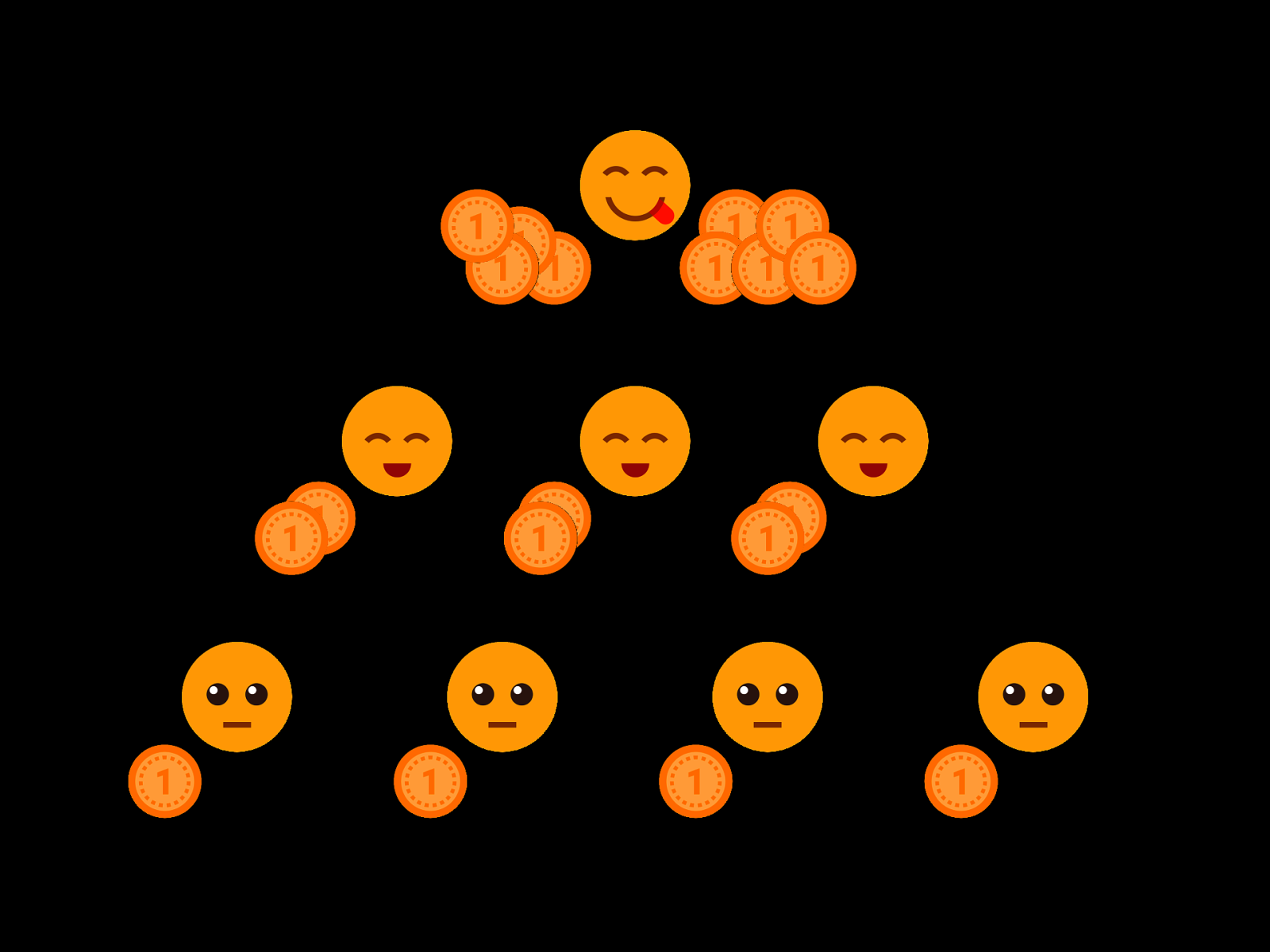

NFTs are emblematic of cryptocurrencies as a whole. The benefits come from getting in early and building hype to raise the value of your stake. Much like a pyramid scheme, or even a Ponzi scheme structure, the value is inflated as the system scales to more people. But the wealth usually remains concentrated in the hands of those who got in early.

So Web3 certainly isn’t decentralising wealth.

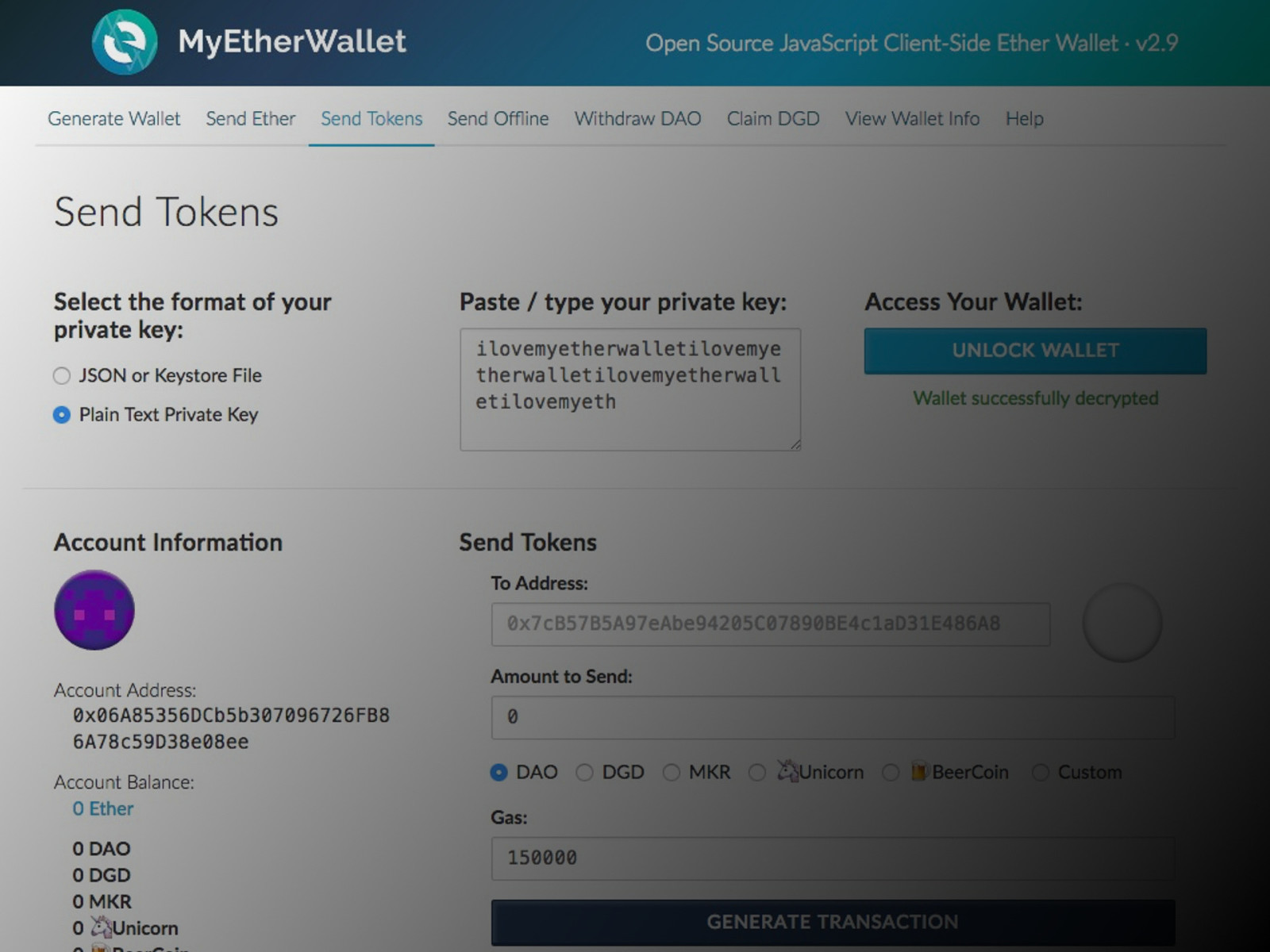

As Web3 is focused on cryptocurrency and financial incentives, it follows that your “decentralised identity” in Web3 is your wallet.

Some web browsers, such as Brave, come with cryptocurrency wallets built-in, and you can also get browser extensions to use your wallet.

You can host your own wallet if you have the technical knowledge, skills and time, but it has to be hosted and secured by you. So if you forget your password, wave goodbye to your cryptocurrency.

Understandably most people opt for a wallet hosted by an intermediary who looks after your cryptocurrency on your behalf.

(No, don’t be silly; that’s nothing like a bank or PayPal.)

Unlike physical wallets, a cryptocurrency wallet doesn’t store the currency itself… that’s stored on the blockchain. Instead, the wallet is used to keep your “keys”. Every wallet has a unique pair of keys, like addresses, where one key is private, and the other is public. The private key is used to verify transactions on your behalf, and the public key is used as an address so that others can send you cryptocurrency.

Once you’ve got a wallet, you can use it as your identity with any compatible Web3 dApp or DAO. That means you don’t need to use OAuth, sign up or create an account to get access to dApp or DAO activities, and it’s what Web3 folks mean when they say “permissionless.”

You can keep your wallet identity private and anonymously participate in the Web3 community. However, to receive any cryptocurrency, you need to provide your public key address. If a person or organisation has access to your address, they can see all of your transactions and how much currency is in your possession.

This is the flipside of blockchain transparency; you have no privacy around your transactions unless you use a cryptocurrency wallet intermediary that has layered on additional privacy protections.

Now, if you’ve been on the receiving end of harassment and abuse online, you might have alarm bells going off in your head right now, and for a good reason.

“Imagine if, when you Venmo-ed your Tinder date for your half of the meal, they could now see every other transaction you’d ever made—and not just on Venmo, but the ones you made with your credit card, bank transfer, or other apps, and with no option to set the visibility of the transfer to “private”.”

“The split checks with all of your previous Tinder dates? That monthly transfer to your therapist? The debts you’re paying off (or not), the charities to which you’re donating (or not), the amount you’re putting in a retirement account (or not)?”

“The location of that corner store right by your apartment where you so frequently go to grab a pint of ice cream at 10pm?

Not only would this all be visible to that one-off Tinder date, but also to your ex-partners, your estranged family members, your prospective employers.”

“An abusive partner could trivially see you siphoning funds to an account they can’t control as you prepare to leave them.”

“As for the marketing machines and predictive algorithms that currently suck in every scrap of data they can to determine what ads to show you, or evaluate your suitability for a mortgage, or try to predict if you’ll commit a crime? Well, they’ve just hit the jackpot.”

One solution for the lack of privacy in cryptocurrency wallets is to have multiple wallets for different purposes, keeping most of your own transactions in an unshared wallet. Using multiple wallets is a recommended security practice by many in the cryptocurrency world. But how easy is it to keep track of all your wallets? Including who has access to which wallet and the keys for all of them separately? That’s not a workable solution for most of the population, especially those without technical experience.

The permanence of the blockchain means a record is kept of every transaction. So any terrible item shared using the blockchain is stored on that blockchain forever. Whether it’s revenge porn, child abuse images, hate speech or harassment.

Some forms of moderation are possible on the blockchain. Platforms built on a blockchain can choose not to display a transaction from that blockchain. But the hidden transaction will still be visible on any other copy of that blockchain.

We do need better transparency and permanent records in many areas of society, especially to hold governments and corporations to account.

But Web3 flattens hierarchies in a way that creates little difference between an individual person, a corporation or a government.

There are some aspects of Web3 I’ve not spoken about today. The definition of Web3 and what qualifies as a Web3 project is debatable and largely depends on which article you read or tutorial you follow.

But I should still mention the metaverse. It’s an “extended reality” consisting of 3D spaces in virtual reality where people can interact with each other. And pay for everything using tokens.

Network-connected virtual worlds aren’t new; Second Life came out 19 years ago and already has its own marketplace and virtual token-based currency, which isn’t based on blockchain and doesn’t have any value outside of Second Life.

What’s probably most intriguing about the metaverse is Facebook’s interest in the space. (And by intriguing, I mean repulsive.) The metaverse is why Facebook changed its name to “Meta”, creating its own metaverse where you can basically live inside Facebook. Scary, right? The decentralised principles of Web3 and Facebook seem like a mismatch when you consider how much Facebook has profited from being a relatively inescapable centralised platform.

It makes you question who gains from Web3?

Web3 is popular with developers, and if you’re into development or creating anything on the web, it’s easy to understand why. People often get into tech because they enjoy nding new technologies to explore and build upon. But they’re not the only ones getting big benefits from Web3.

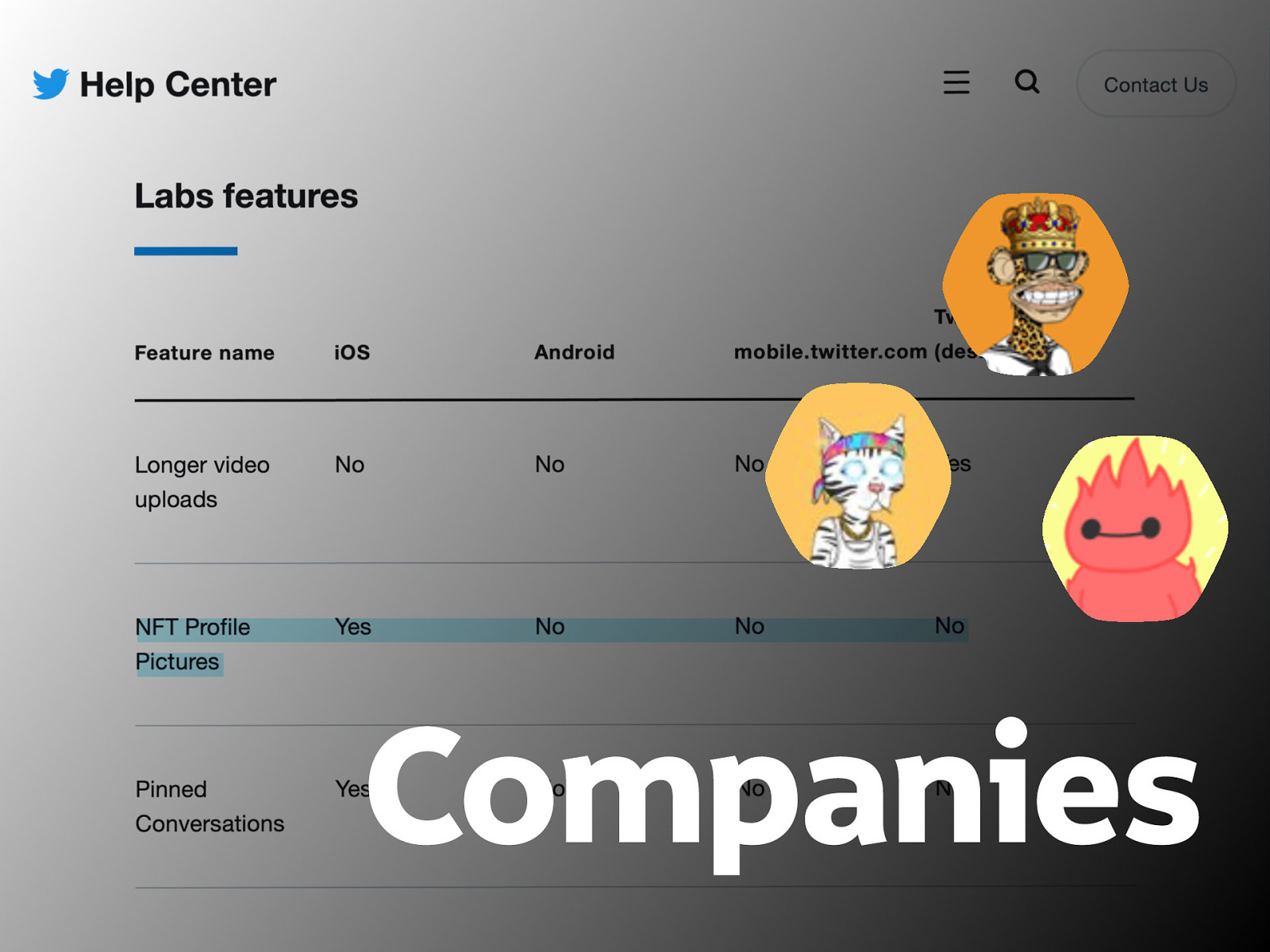

If you’ve heard people in the web community bitching about hexagons, it’s because they’re probably lamenting Twitter’s NFT profile pictures. Subscribing to Twitter’s Blue subscription and connecting a cryptocurrency wallet enables a person to use their NFT as their profile picture, differentiated by a “soft” hexagonal frame rather than the round frame used for the average NFT-free profile pictures.

Much like Reddit’s use of tokens, Twitter’s implementation of NFT profile pictures isn’t decentralisation, and it’s merely brushing up against a blockchain rather than building upon it.

Twitter is exemplary of many companies embedding Web3 or Web3-adjacent tech. They’re using the wave of hype around the buzzwords on top of their own popularity and scale to cash in with a group of users willing to spend money for bragging rights.

The excitement that venture capitalists have for Web3 is also suspicious. These are the same people who invested in Web 2.0 platforms and profited from centralisation, keeping users where their firms were making money. Andreessen Horowitz, a massive venture capital firm, recently announced a $4.5 billion fundraising round to support startup projects related to blockchain and Web3 technology and has already invested in OpenSea and Coinbase, two of Web3’s biggest names. But venture capital invests money in return for ownership, which means centralised control.

That’s not exactly decentralised power.

As with any kind of investment, the early adopters of cryptocurrencies benefit the most. And the more hype there is around Web3, including noise on social media and people debating its significance, the easier it is to convince others to invest. Whether it’s another individual buying some cryptocurrency and pushing the value up or getting the attention of a venture capital firm to pump money into your Web3 initiative.

The hype machine is the money machine, and that’s why you hear so much about Web3.

Honestly, I don’t blame folks who are suffering under the current system for using cryptocurrencies and NFTs as a way to get themselves out of a perpetual struggle for existence.

But to paint Web3 as a route to a more democratic and egalitarian society is ridiculous. At best, you could be perceived as naïve, but at worst, you are conveniently hyping an initiative where you stand to gain significant wealth as a direct result of your hype.

We do need decentralisation, we need to get away from Big Tech, and blockchains could have some practical cryptocurrency-free applications for holding corporations and other governing bodies to account.

But you can’t escape the environmental impact when your structure is wholly reliant on proof of work blockchains and cryptocurrency.

And it bears repeating, with participation being the route to financial compensation, Web3 still encourages centralisation of power.

And who has that power? This brings me to another fundamental flaw in the Web3 community, the Web3 community itself. I just don’t see how the community is any different from those who built the centralised platforms of Web 2.0. They’re primarily young white cis non-disabled men, similar to the people who were happy to exploit and monetise others for the sake of building wealth for themselves. And they’re people most able to build with the complexities of Web3.

Web3 is not inclusive. Participation in Web3 requires a lot of knowledge. You need to understand the concepts and the space, not just to build upon them but to protect your personal security and privacy and prevent yourself from getting scammed. And few people in the community are using their expertise in Web3 to make wallets, DAOs and dApps accessible to everyday people with little technical knowledge.

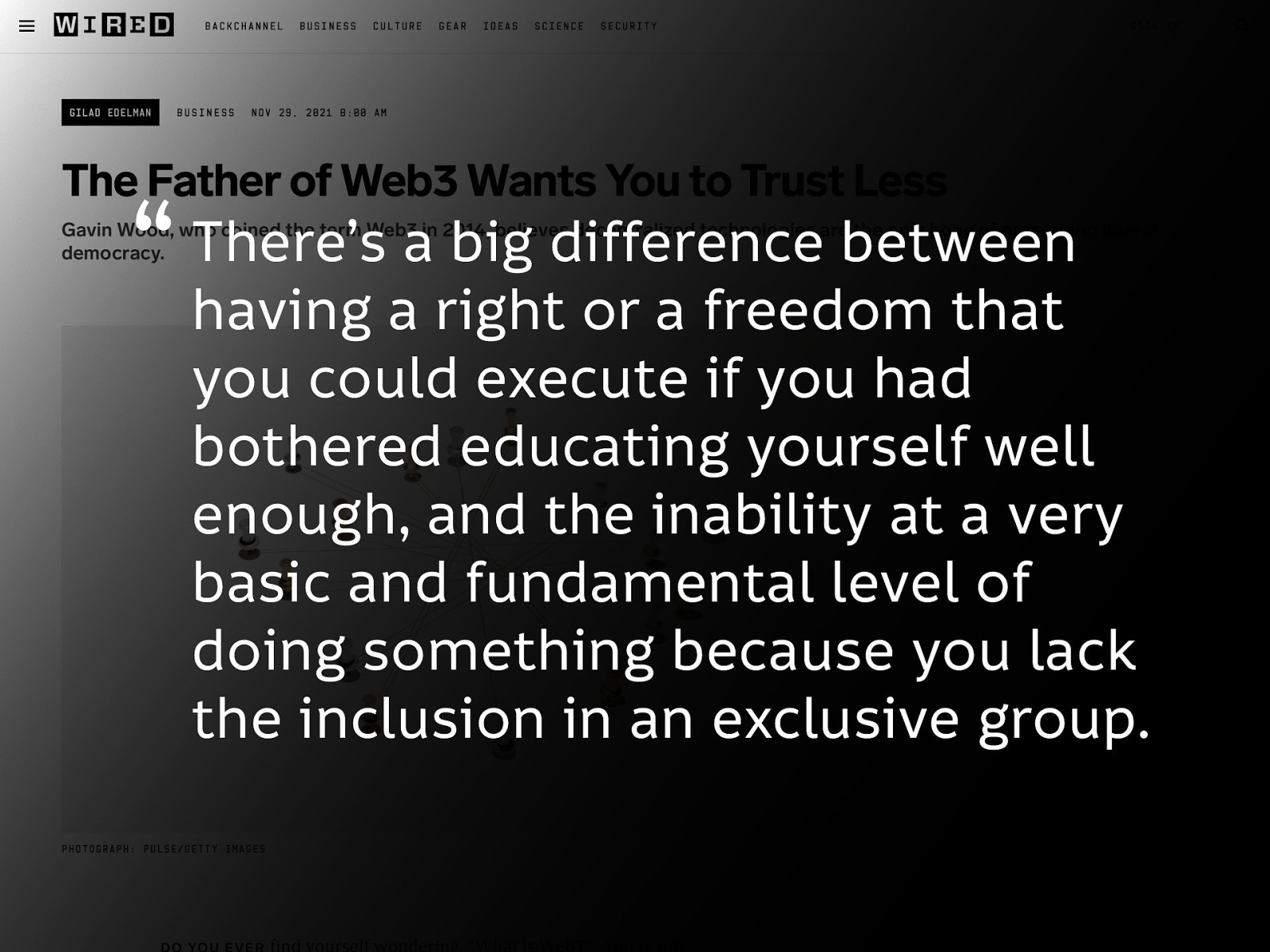

At the beginning of this talk, I said I’d come back to Gavin Wood, the guy who came up with the Web3 term. When Gavin was pressed on the high barrier to entry in participating in Web3, this is what he said:

“There’s a big difference between having a right or a freedom that you could execute if you had bothered educating yourself well enough, and the inability at a very basic and fundamental level of doing something because you lack the inclusion in an exclusive group…”

“If I educate myself well enough on material that is freely available, and that’s all that is required to become a co-provider of the service, then that is a free service.”

Gavin Wood is saying everyone has equal access to Web3, and if you feel it’s too difficult, that’s because you’re too lazy to learn.

This is probably considered a perfectly reasonable thing to say if you’re a person already wealthy in both money and time. But if new technology requires a lot of time, resources and existing knowledge to participate, then it will inevitably reproduce the same power imbalances we already see in technology today. Except perhaps more developers are kings.

Your movement is not egalitarian when only those who have plenty of free time, probably those already supported by secure high-paying jobs, with few dependents, have the time to learn the required knowledge and build the skills to participate. Or those who have the currency to pay their way in or the hardware to generate the computational power.

Making your resources inclusive to everyone has to be part of your plan for creating new technology. Otherwise, your talk of creating a more egalitarian society becomes nothing more than a selfish justification for environmental destruction.

You don’t care about everyone participating in this technology; you just care about you being able to participate.

The same applies to community ownership. Having your technology be owned by the community is a noble goal. But that community must be accessible and inclusive. Otherwise, you just get reproductions of the existing toxic communities led by those who have time and resources to participate.

And a toxic community is a red flag. Honestly, I was anxious to give this talk. Three years ago, I gave a talk about inclusivity in decentralisation at an Ethereum conference. It was supposed to be one of the “nice” communities. I went back to my hotel room and sobbed at the end of the day. It was exhausting being confronted by so many people who questioned my right to speak at that event because they didn’t like my constructive criticism. The next day I woke up to posts dismissively calling me a Social Justice Warrior…

And sure, that’s not a gotcha. If you want to accuse me of fighting for causes in the area of social justice, I’ll take it as a compliment. - That is why I’m talking at an event about design ethics on this very topic.

A community that cares about being better than what came before has to be open to criticism and change.

I’ll be the first to admit I’m a cynical old hag when it comes to tech. I’ve been in the industry long enough that it’s hard to genuinely enthuse me with technology. But that’s not because I’m nostalgic for how technology once was; Web 1.0 was hardly an inclusive paradise. I think there is a better way; we’ve just not got there yet.

I’ve been working at, and co-founder of, not-for-profit organisations researching decentralisation for nearly eight years now. I’ve been immersed in many communities in the area. Yes, I am biased because I believe that Small Technology Foundation’s work has promise, but I don’t think we’re the only people capable of building alternatives to Big Tech.

I’ll say it again: We do really need decentralisation. We need to break down the current power structures and distribute ownership to communities and individuals. We need to regain control over our personal information.

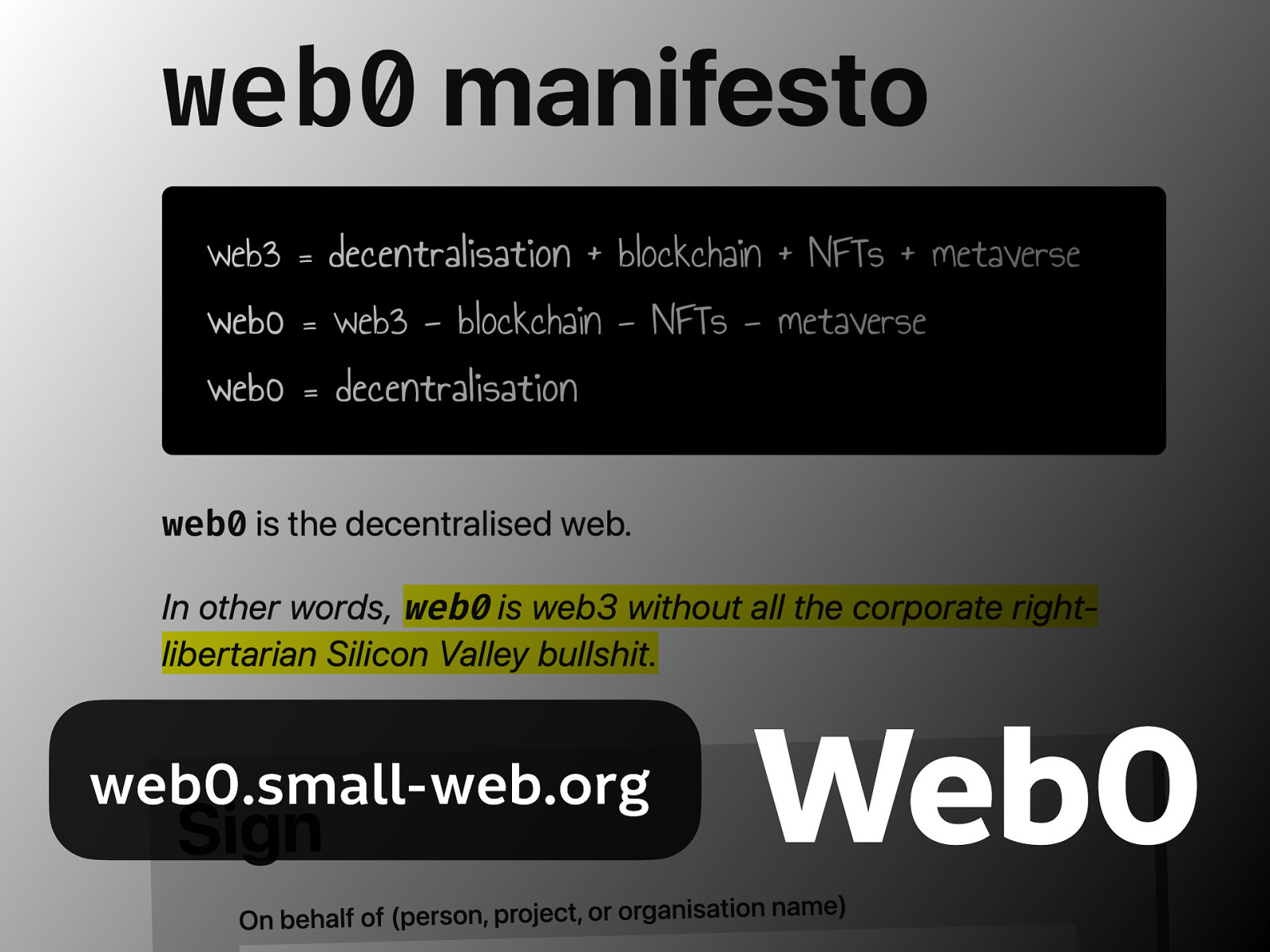

This is why Aral Balkan, the other co-founder of Small Technology Foundation, created the web0 manifesto. He wanted to highlight the benefits of decentralisation while rejecting blockchain, NFTs and the metaverse.

As people who build on the web, it’s our responsibility to seek out ethical alternatives to mainstream technology.

Sure it’s entertaining to dunk on NFTs on social media, but we also have to address unethical actions with seriousness. Use our knowledge of technology for real criticism. Prevent scammers from taking advantage of vulnerable people.

Web3 is a fun buzzword used by a group of people who believe our use of the web will evolve into a digital land-grab where you can monetise absolutely everything with the help of environment-destroying technology.

Web3 is nowhere near as popular as social media suggests. Let’s go back to the people heralding the “coming movement” of Web3. It’s important to note that Web 1.0 was a retronym, only named after the movement was over. And Web 2.0 was well underway before its name was popularised. Web3 is nowhere near as popular as the floods of posts on social media suggest.

Web3 is clever branding, and it is not inevitable as the name implies. In most implementations, Web3 isn’t the revolution it claims to be, with far more centralisation and similarities to Web 2.0 than its defenders care to admit.

Whether that’s delusional or predatory, I’ll let you decide.

Laura Kalbag: laurakalbag.comsmall-tech.org