Accessible unethical technology

Laura Kalbag, laurakalbag.com@LauraKalbag. Small Technology Foundation, small-tech.org.

A presentation at Accessibility Scotland in October 2019 in Edinburgh, UK by Laura Kalbag

Laura Kalbag, laurakalbag.com@LauraKalbag. Small Technology Foundation, small-tech.org.

Since I wrote a book about accessibility, I’ve had many people excitedly share with me their organisation’s work with accessibility. It’s great, I learn so much from it, and I love it. However, too often the organisations these good people work for are … not so good.

While my book is about accessibility, and accessibility is a core value in all my work, my job is not entirely being an advocate for accessibility. I’m not an expert like the other speakers here today. My job is the co-founder of Small Technology Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation advocating for, and building technology that protects and personhood and democracy in the digital network age. Ethical technology.

And while inclusivity is a key part of ethical design, this still leaves me with something of a conundrum. I want to be excited about the brilliant work people are doing in accessibility, but I don’t want that work to be used to exploitative and unethical ends.

I keep coming back to a wise tweet by the great Heydon Pickering:

“Not everything should be accessible. Some things shouldn’t exist at all.”

But what are the things that shouldn’t exist? What defines unethical technology? What follows is an incomplete list of some ways (specifically Internet) technology can be unethical:

Inequality in distribution and access is a key issue for those of us here today. The lack of accommodations for many disabled people could often be considered discriminative. The same goes for the lack of access for poor people, people who can’t afford the latest devices, or expensive data plans.

Many of the ethical issues in technology comes down to accountability and responsibility (or a lack thereof.)

Centralised platforms encourage indiscriminate sharing, which results in the rapid and viral spread of misinformation.

Extracting personal information from every data point of what a person shares online, their devices, their locations, their friends, their habits, their sentiments, is an invasion of a persons’s privacy, and is done so without their true consent.

Using the extracted personal information to make automated decisions. Like whether someone would be the right candidate for a job, or qualify for credit, or is a potential terrorist. (It is usually irrelevant whether those decisions are based on inaccurate or discriminatory information.)

The profiling and targeting of individuals enables manipulation by the platforms themselves, or by advertisers (or data brokers, or governments) utilising information provided by the platforms.

Particularly in situations where a platform collects people’s personal information, including credit card information, it is irresponsible to not adequately protect that information. It is a risk to store this information in the first place, and if we do, we must ensure it is stored securely.

Whether it’s the business model, the management, designers and developers, or anybody else in the organisation, often organisations do not care to address the impact of their work, or worse, deliberately design for harmful outcomes that deliver them more power and/or money.

These are topics that have been explored in depth recently by Tatiana Mac, who invokes “intent does not erase impact” to describe our often-haphazard approach to designing technology.

In her brilliant A List Apart article, ‘Canary in a Coal Mine: How Tech Provides Platforms for Hate’ she explains:

“As product creators, it is our responsibility to protect the safety of our users by stopping those that intend to or already cause them harm. Better yet, we ought to think of this before we build the platforms to prevent this in the first place.”

People usually say “ask for forgiveness, not for permission” to encourage each other to be more daring. Instead, I think we require the approach, “ask for permission, not for forgiveness.”

Now that people are starting to take the climate crisis more seriously, it’s time to reckon with the environmental costs of Internet technology at scale. The impact of running massive server farms, of blockchain technology turning electricity into currency, of machine learning using vast quantities of energy.

There are ethical considerations in business, which apply to any industry, but are exacerbating factors when combined with inequality in distribution and access, a lack of accountability and responsibility, or environmental impact:

Once you sign up for a product or service, it is difficult to leave. To some, this could be a minor inconvenience, but if your privacy is being routinely violated, the requirement to leave becomes paramount.

What’s worse is if no alternatives exist. What if the only social platform we can use is one that environmentally damaging? What if the only way we can participate in civil society online is inaccessible?

Earlier I mentioned profiling being one of the key ethical issues in technology today.

Profiling is enabled by tracking; in order to develop profiles of you, they need data points. Those data points are obtained by tracking you, using any kind of technology available.

I didn’t ever picture myself spending my days examining the worse of the web. But here I am.

I’ve worked on Better Blocker’s tracker blocking rules for the last four years, trying to work out what trackers are doing, why they’re doing it, and blocking the bad ones to protect the people who use Better Blocker. And as much as I try to uncover bad practices, block and break invasive trackers, they keep getting sneakier, and more harmful.

So what is a tracker? What is the kind of stuff I block?

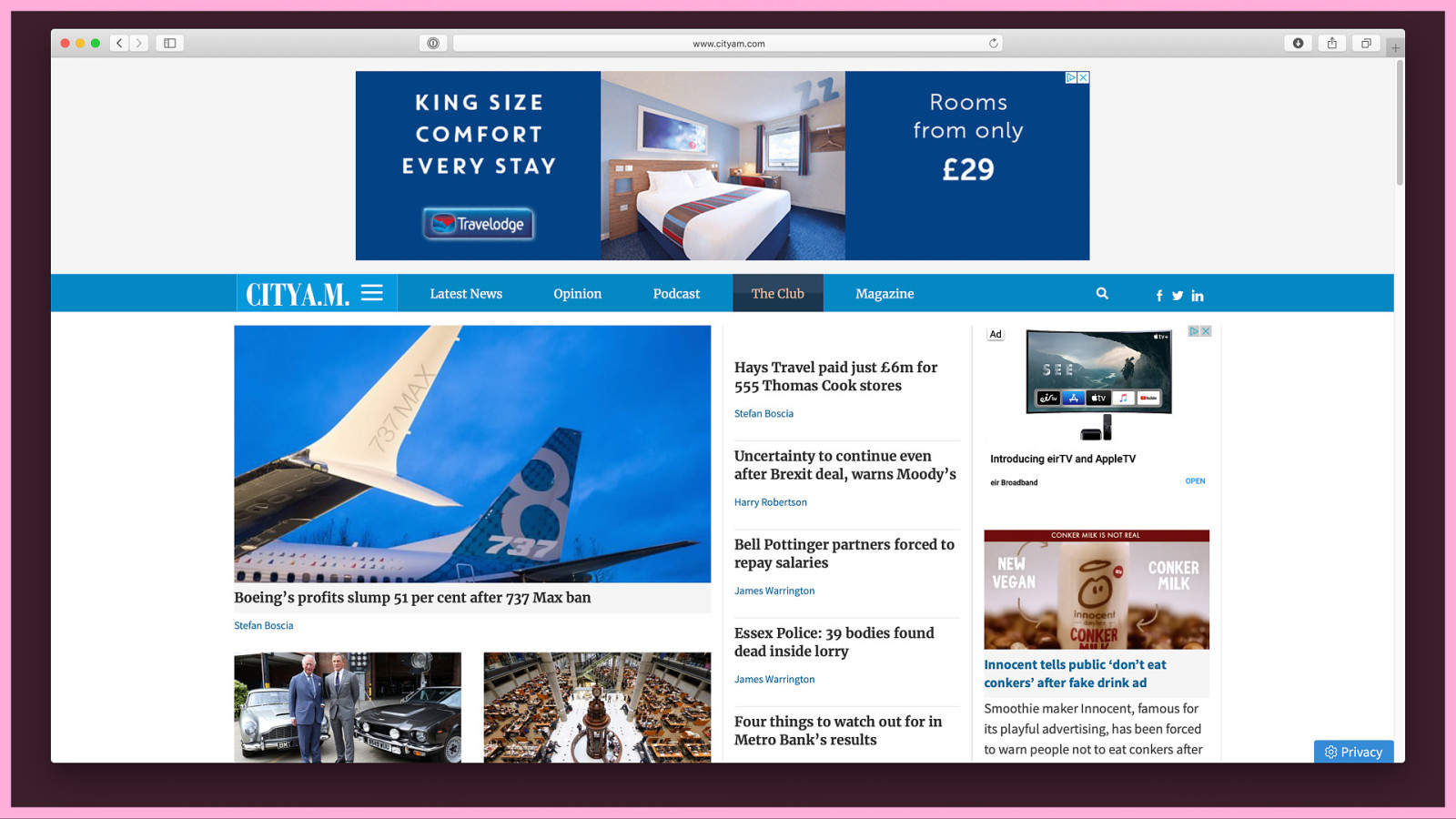

I visit the City AM site, because I’m well into business news. I want to look at the third-party resources that it uses. Third-party resources are usually a good indicator of basic trackers, as third-party services can track you across the web on all the different sites that use them.

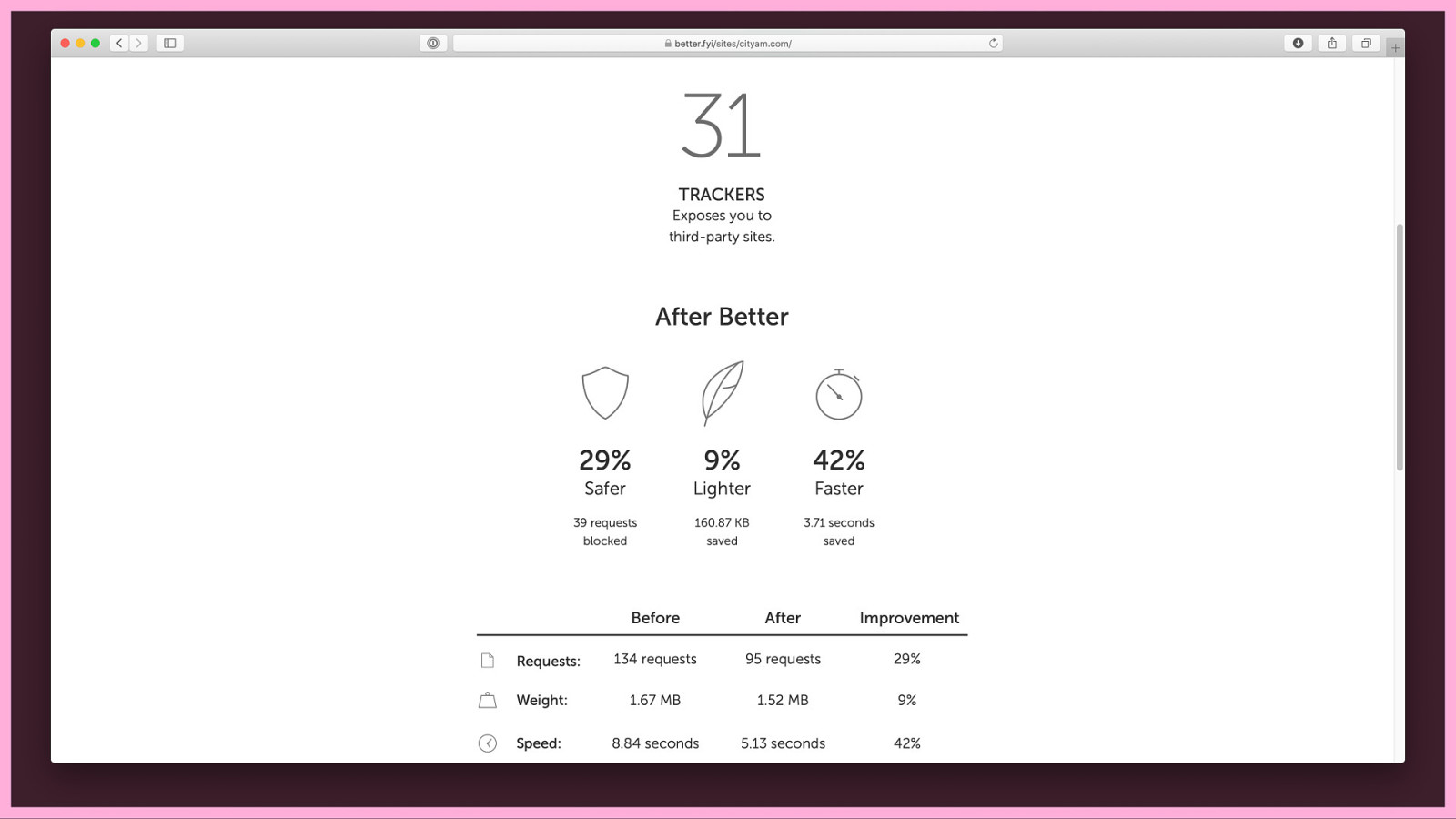

A quick inspection of City AM reveals 31 third-party trackers. For a news site, that’s low to average. I pick out one tracker at random:

I have a look at our statistics for all the sites we’ve found that call a resource from adnxs.com. It’s on 16.9% of the top 10,000 sites on the web. We class that as a pandemic.

So I chuck adnxs.com into a browser to work out what it might be. It’s “AppNexus”…

…and it “Powers The Advertising That Powers The Internet.” Apparently “Our mission is to create a better internet, and for us, that begins with advertising.” Well, I’m not sure many people would share that opinion.

I scroll on down to find their privacy policy, which is usually tucked away in a footer in tiny text that they wish was invisible.

A quick browse of the privacy policy alongside the script itself, and I come to understand that the AppNexus tracker is tracking visitors to create profiles of them. These profiles are then used to target ads to the visitors for products they might find relevant.

We all know targeted ads, when the same products follow us around the web. For example, on Facebook I get a lot of ads for women in their 30s: Laundry capsules, shampoo, makeup, dresses, pregnancy tests…

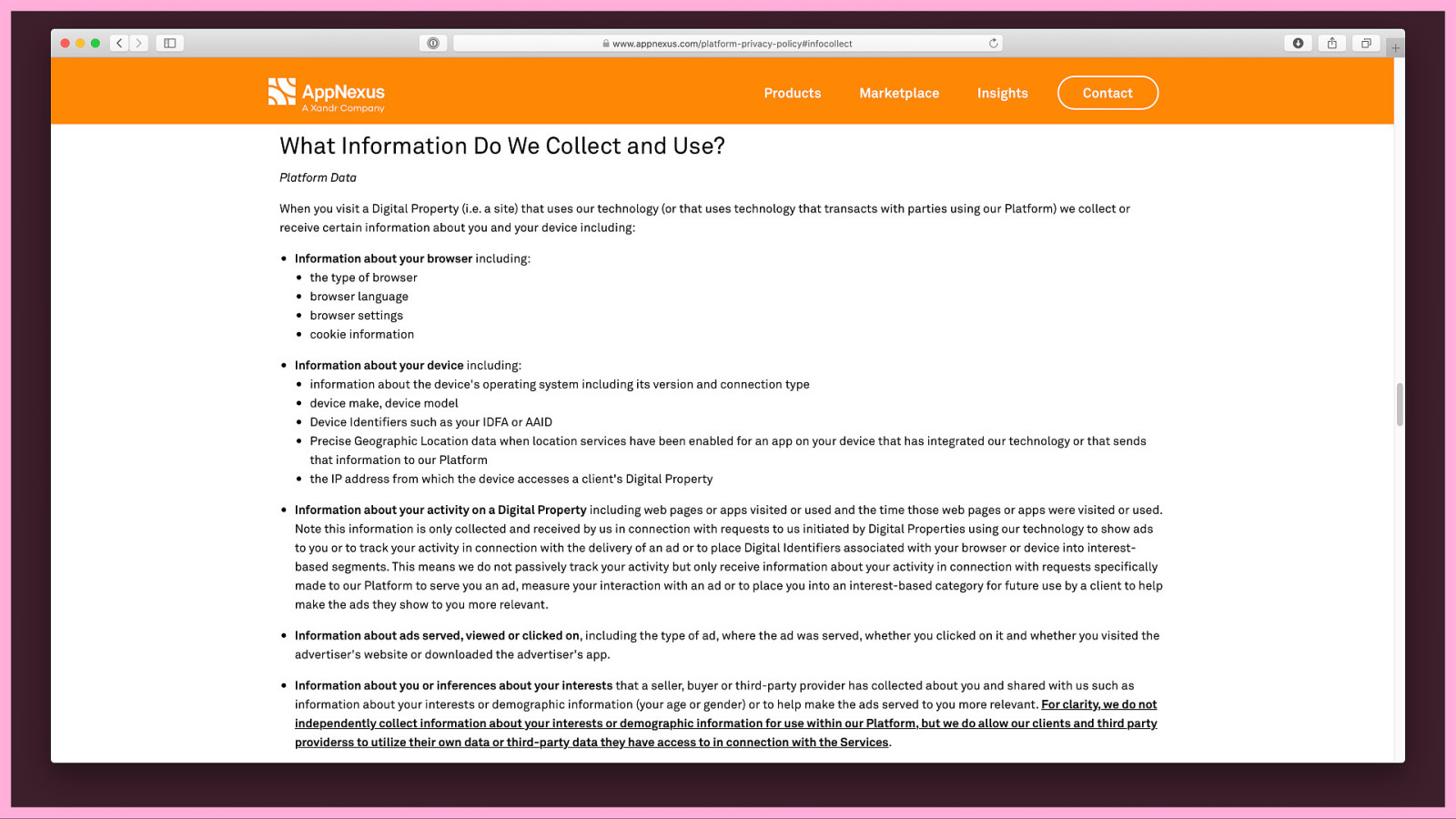

Back to the AppNexus privacy policy… Conveniently, they have a section detailing ‘What Information Do We Collect and Use?’

This includes a long long list, so I’ve picked out some particularly interesting/scary data points:

(They go to great lengths to emphasise that they do not collect the interests info themselves, they just get it from other people…)

I’m curious about what these interests might be. What might AppNexus know about me?

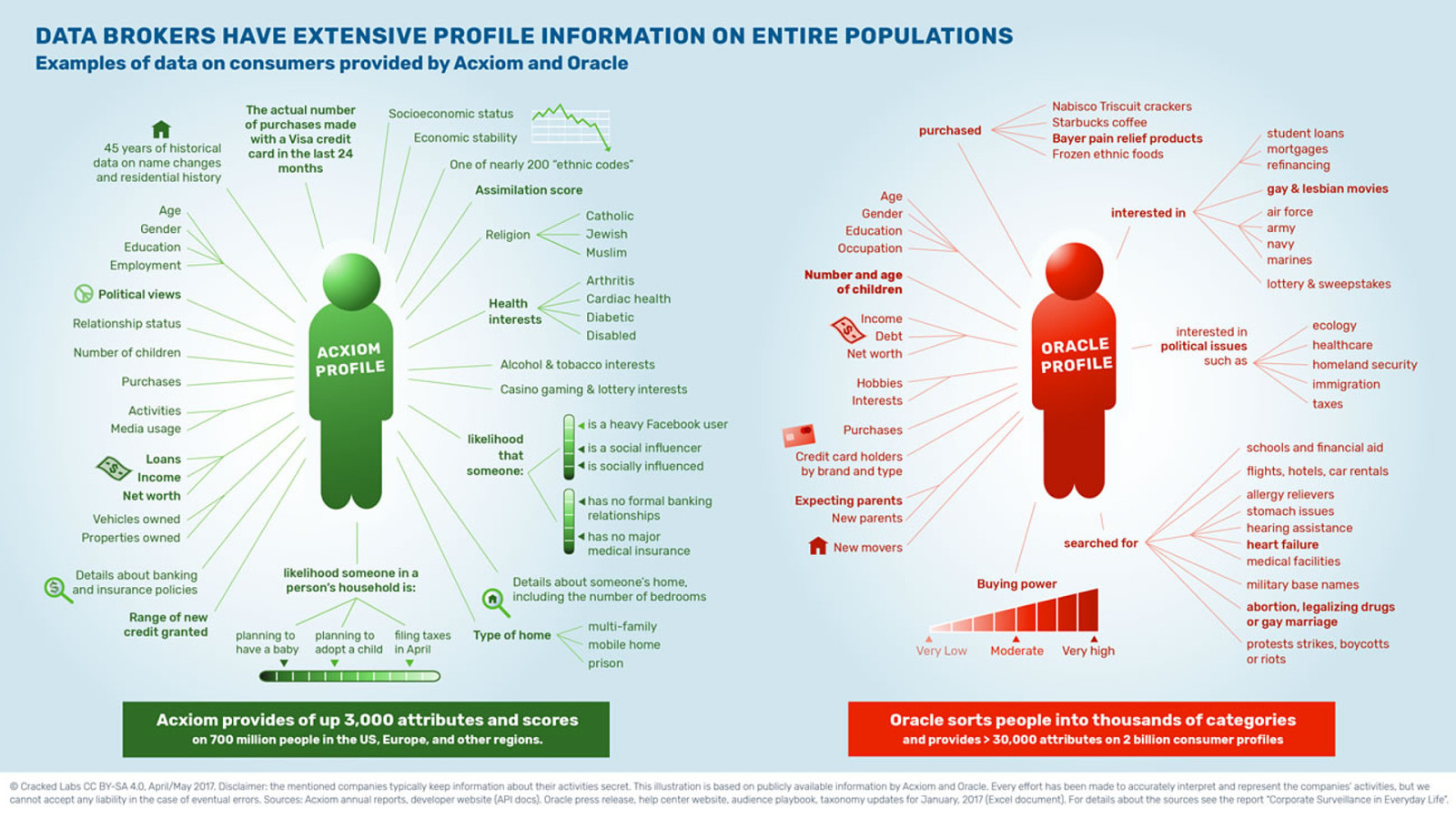

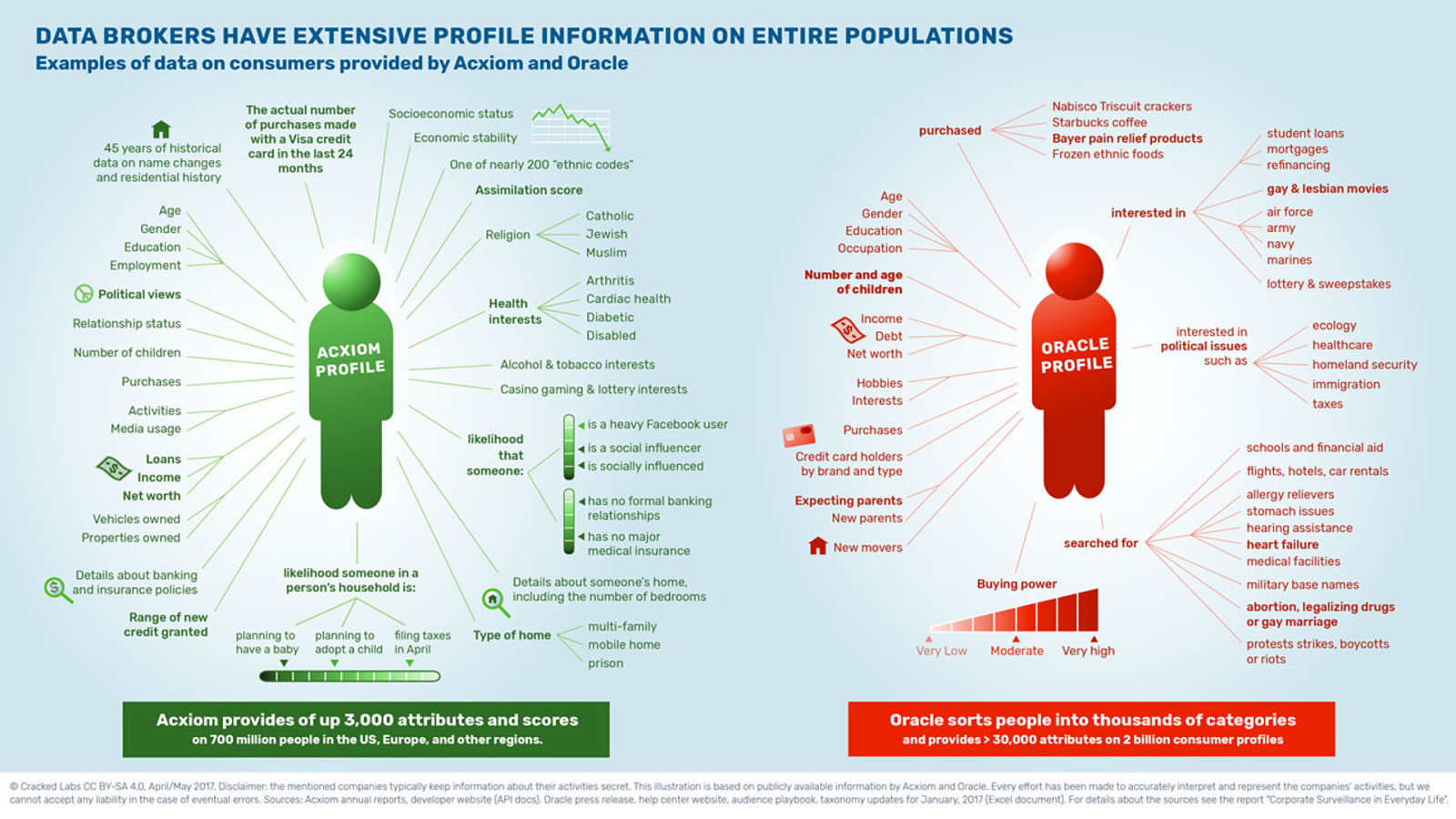

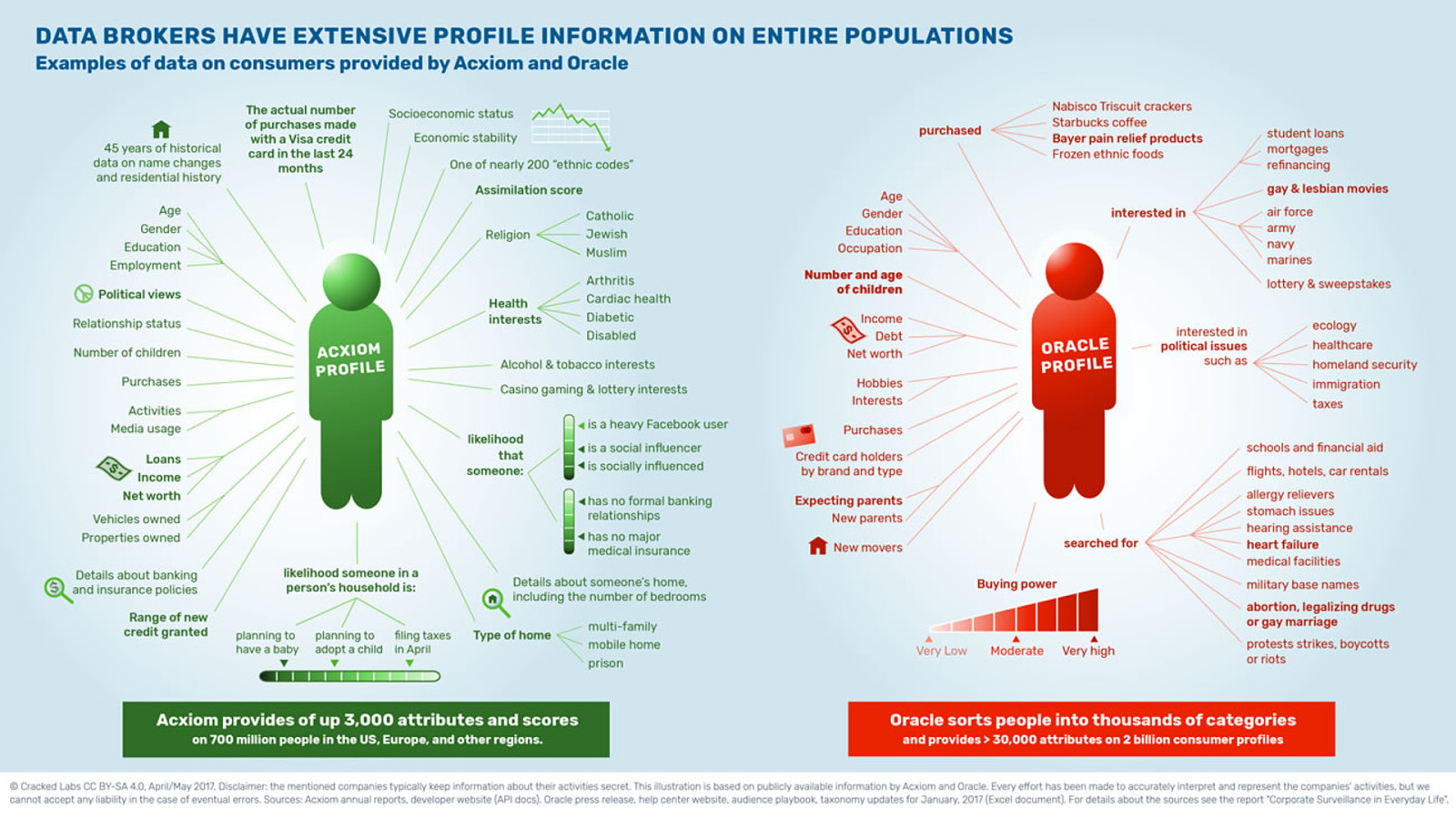

Cracked Labs have done multiple reports into the personal data that corporations collect, combine, analyse, trade and use.

Much of the combining, analysing and trading of data is done by data brokers.

Two of the biggest data brokers are Oracle and Acxiom.

According to Cracked Labs: “Acxiom provides up to 3000 attributes and scores on 700 million people in the US, Europe, and other regions.”–Wolfie Christl

And “Oracle sorts people into thousands of categories and provides more than 30,000 attributes on 2 billion consumer profiles.” But what are those attributes and categories?

Again, I’ve picked out some of the creepiest bits of information:

It’s not just the data brokers that are doing this, most platforms are creating profiles of you, using them to target you and organise your “personal feeds” to keep you engaged and interested in their sites.

These attributes can be used to target you with advertising, not just for products you might like, but including the ads that political parties put on Facebook. That’s what the Cambridge Analytica scandal was about. Political parties having access to not just your attributes but your friends’ attributes and your friends’ friends’ attributes.

And it’s no longer just your personal information and its patterns, or your habits. Facial recognition and sentiment analysis is also being used to create a deeper profile of you.

I could talk about this in more depth for much longer, but I’ve just not got the time. But the book Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff contains both the history and the predicted future of these massive complex surveillance systems:

“Surveillance capitalism unilaterally claims human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data. Although some of these data are applied to product or service improvement, the rest are…fabricated into prediction products that anticipate what you will do now, soon, and later.”–Shoshana Zuboff

How can we protect ourselves (as individuals)? I’m not talking about security tips (passwords, two-factor authentication and things like that…), I’m talking about how to protect yourself from tracking by the websites you’re visiting and the third-party services they employ on those websites.

Avoid logging in. (If you can.) For example, when you’re watching videos on YouTube. Many platforms will still track you via your IP address, or fingerprinting, but whatever you can do to minimise them connecting your browsing habits with your personal information will help you stay protected.

Avoid providing your real name. Of course this is trickier in professional settings, but where you can, use a pseudonym (a cute username!) to prevent platforms from connecting the data they collect about you to further data from other platforms.

Use custom email addresses.…

For example, when you’re signing up for a platform, use an email address like twitter+email@emailprovider.com. Many email services support using custom email addresses like this, and will forward any emails to that address to your primary inbox.

Avoid providing your phone number. Folks in privacy and security recommend using two-factor authentication to prevent nefarious strangers from getting into your accounts. But be aware that phone numbers are a little risky for authentication…

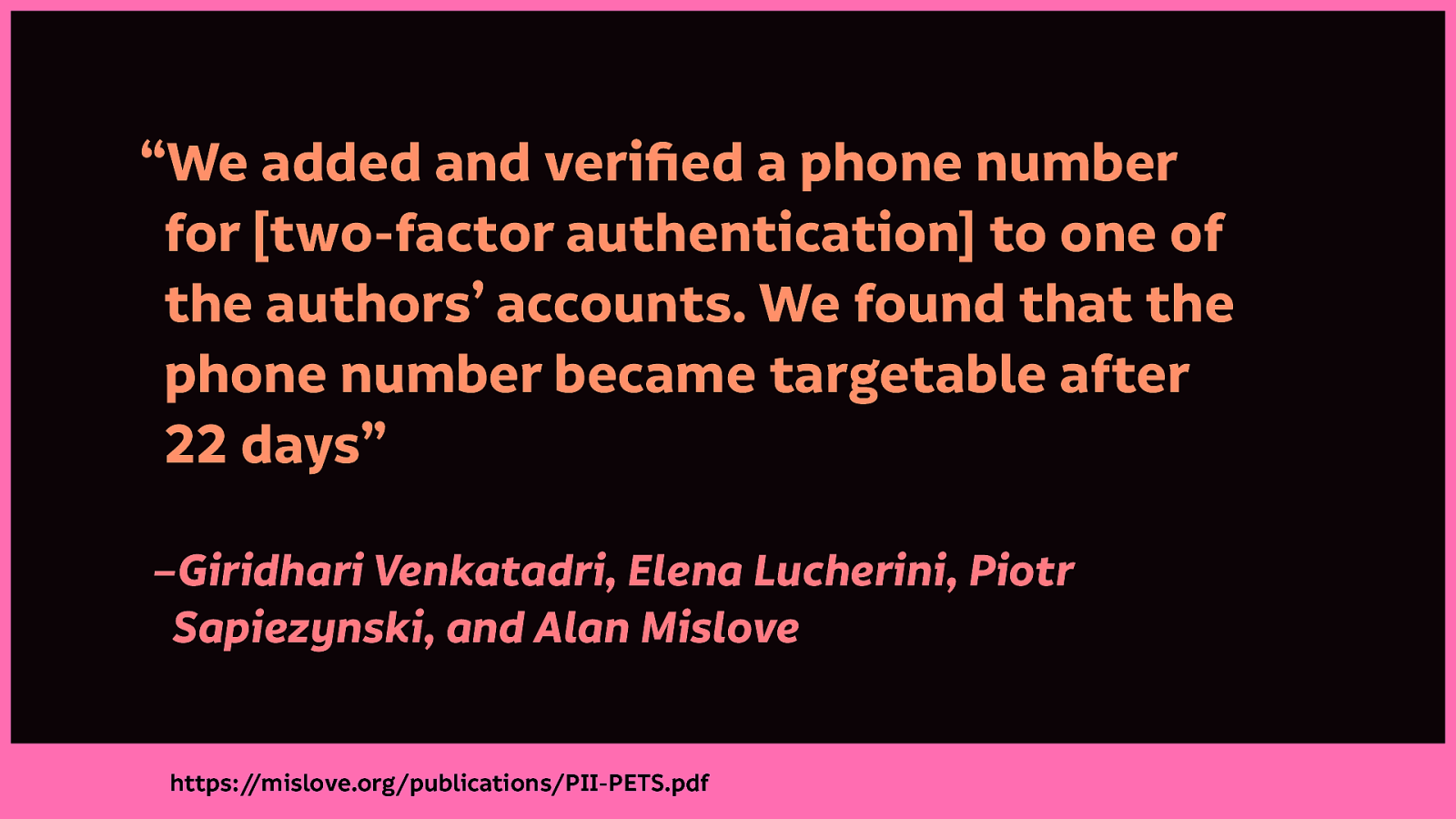

A study into whether Facebook used personally-identifiable information for targeted advertising found that when “We added and verified a phone number for [two-factor authentication] to one of the authors’ accounts. We found that the phone number became targetable after 22 days”—Giridhari Venkatadri, Elena Lucherini, Piotr Sapiezynski, and Alan Mislove

And not long ago, Twitter admitted they did the same thing: “When an advertiser uploaded their marketing list, we may have matched people on Twitter to their list based on the email or phone number the Twitter account holder provided for safety and security purposes.”

Use a (reputable) Virtual Private Network (VPN). VPNs will obscure your location, making it harder to track you and associate your browsing habits with you as a individual. But make sure they don’t spy on your browser traffic themselves. (Be very suspicious of the cheap/free VPNs!)

Use private browsing or browsing containers. When you login to a platform, do so in a private window or container. Usually this will ensure that any cookies set during your session will be discarded when you close that window or container.

Log out. Help prevent platforms from continuing to track you on other sites (especially social media buttons!) by logging out. I once found a site sending the articles I was viewing back to Instagram because I was still logged in.

Disallow third-party cookies in your browser preferences. This might break a lot of sites, but where you can, it’ll protect you from quite a bit of tracking.

Use a tracker blocker…

Far be it for me to recommend something I build myself, but we built Better Blocker out of necessity. It doesn’t block everything, but it does block a lot.

We also recommend uBlock Origin for platforms that support it (Most tracker blockers will also track you, uBlock Origin is privacyrespecting.)

Use DuckDuckGo, not Google search. Google has its trackers on 80% of the web’s most popular sites, don’t give it the intimate information contained in your search history. (The symptoms you’re worried about, the political issues you care about, the products you’re looking to buy…)

DuckDuckGo is a privacy-respecting alternative.

Don’t use Gmail. Your email not only contains all your communication, but the receipts for everything you’ve bought, the confirmations of every event you’ve signed up for, and every platform, newsletter, and service you’ve joined.

There are plenty of email providers out there that are privacy-respecting. Two good options are Fastmail…

and Protonmail.

Whatsapp’s message contents may be encrypted, but not who you’re talking to and when you’re talking to them.

There are privacy-respecting alternatives including Wire.

Don’t use Facebook (for everything). I’m very aware that there isn’t really a good alternative to Facebook when your child’s school is using it to communicate, or your friends are sharing baby photos. But when you can find alternatives for chat (Wire can replace Messenger) and Facebook Pages (your own website gives you far more control!), do it.

Seek alternatives to the software you use every day.

switching.software has a great list of resources, provided by people who really care about ethical technology.

Of course, these are all choices we can make once we’re on the web, but we need to be aware of other places where we are tracked.…

And of course, your choices affect your friends and family. Your friends and family’s choices also affect you. You may not be using Gmail, but if you email somebody who does, Google still gets some information about you. You may not use Facebook, but Facebook still has shadow profiles for people added via their friend’s contacts lists.

This all seems like a lot of work, right? I KNOW! I advocate for privacy and I don’t have the time or the resources to do all of this all the time.

That’s why it’s unfair to blame the victim for having their privacy eroded.

Not to mention that our concept of privacy is getting twisted by the same people who have an agenda to erode it. One of the biggest culprits in attempting to redefine privacy: Facebook.

Here is a Facebook ad that’s recently been showing on TVs. It shows a person undressing behind towels held up by her friends on the beach, alongside the Facebook post visibility options, “Public, Friends, Only Me, Close Friends,” explaining how we each have different privacy preferences in life. It ends saying “there’s lots of ways to control your privacy settings on Facebook.”…

But it doesn’t mention that “Friends”, “Only Me”, and “Close Friends” should really read “Friends (and Facebook)”, “Only Me (and Facebook)” and “Close Friends (and Facebook)”.

Because you’re never really sharing something with “Only Me” on Facebook. Facebook Inc. has access to everything you share.

Privacy is the ability to choose what you want to share with others, and what you want to keep to yourself. Facebook shouldn’t be trying to tell us otherwise.

Google doesn’t believe in privacy either. Ten years ago, Eric Schmidt, then CEO of Google (now Executive Chairman of Alphabet, Google’s parent corporation), famously said >“If you have something that you don’t want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place.”

To which I respond: OK, Eric. Tell me about your last trip to the toilet…

Do we need to be smart about what we share publicly? Sure! Don’t go posting photos of your credit card or your home address. Maybe it’s unwise to share that photo of yourself blackout drunk when you’ve got a job interview next week. Perhaps we should take responsibility if we say something awful to another person online.…

But we should be worried about what we share online for social reasons, not for privacy reasons. We shouldn’t need to be taking these steps to protect our privacy from corporations and governments.

Right now, the corporations are more than happy to blame us for our loss of privacy. They say we signed the terms and conditions, we should read the privacy policies, it’s our fault.

However, an editorial board op-ed in the New York Times pointed out that the current state of privacy policies are not fit for use:

“The clicks that pass for consent are uninformed, non-negotiated and offered in exchange for services that are often necessary for civic life.”

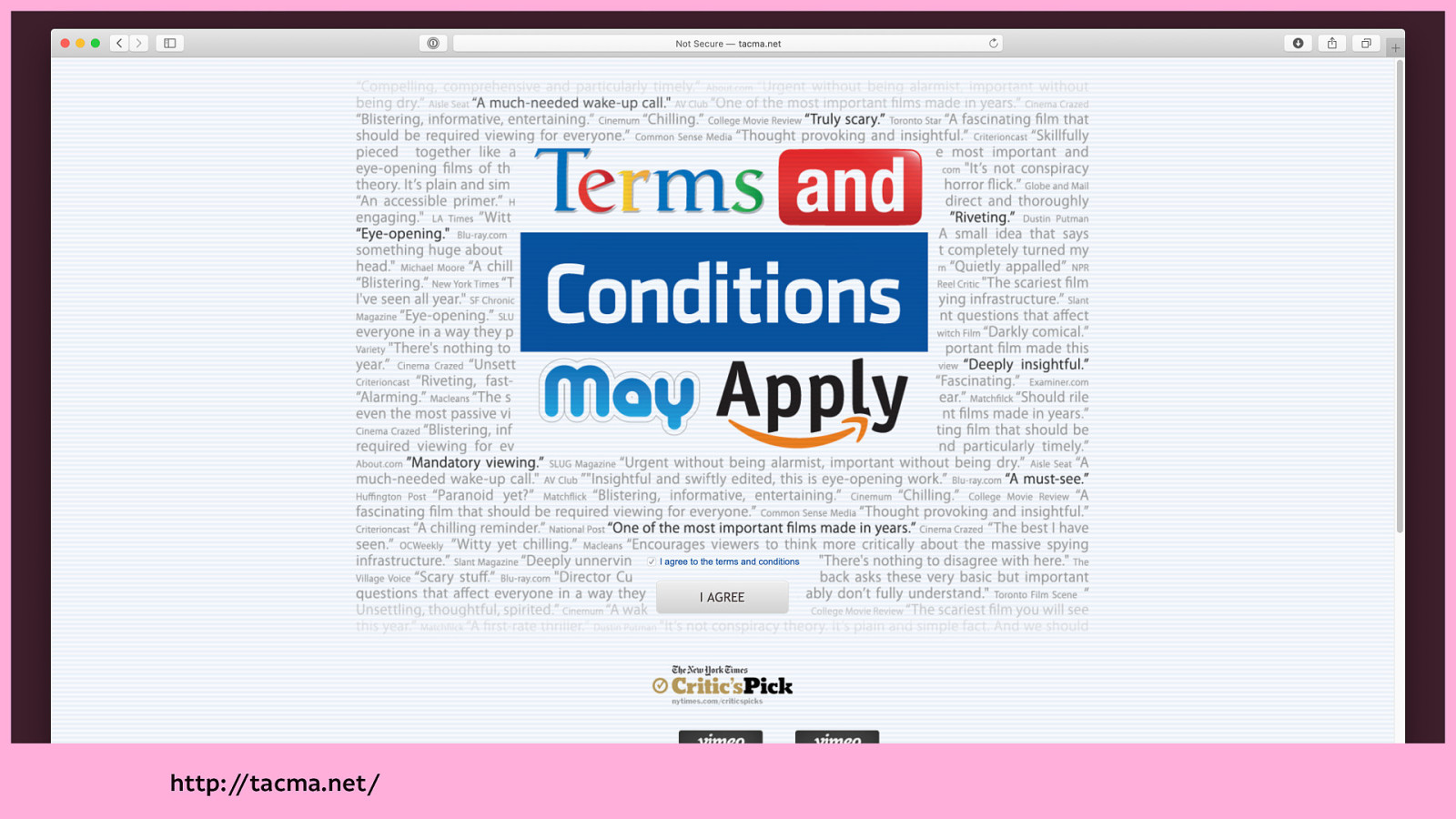

It’s the same conclusion of a whole documentary that was made way back in 2013, called “Terms And Conditions May Apply.”

As part of my work looking into trackers, I often read privacy policies, but even I don’t read the entirety of all the privacy policies for the platforms I use.

In fact, “Two law professors analyzed the sign-in terms and conditions of 500 popular US websites, including Google and Facebook, and found that more than 99 percent of them were “unreadable,” far exceeding the level most American adults read at, but are still enforced.”—Dustin Patar

It’s not informed consent. And how can we even truly consent if we don’t know how our information can be used against us?

And it’s not true consent if it’s not a real choice. We’re not asked who should be allowed access to our information, and how much, and how often, and for how long, and when…

We’re asked to give up everything or get nothing. That’s not a real choice.

It’s certainly not a real choice when the cost of not consenting is to lose access to social, civil, and labour infrastructure.

There’s a recent paper by Jan Fernback and Gwen Shaffer, ‘Cell Phones, Security and Social Capital: Examining How Perceptions of Data Privacy Violations among Cell-Mostly Internet Users Impact Attitudes and Behavior.’ The paper examines the privacy tradeoffs that disproportionately affect mobile-mostly internet users, looking at technology-driven inequalities.

I’ll get more into that later, but for now, I’ll leave you with an excerpt that shows the cost of not giving consent:

“Some focus group participants reported that, in an effort to maintain data privacy, they modify online activities in ways that harm personal relationships and force them to forego job opportunities.”

The technology we use are our new everyday things. It forms that vital social, civil, and labour infrastructure. And as (largely) helpless consumers, there’s often not much we can do to protect ourselves without a lot of free time and money.

Now I want to get into the stuff that I don’t often get to discuss in depth at other events. It’s why I wanted to speak today, get your thoughts. Things that I wrestle with, that constrain me, and I hope you’ll endure me if I don’t quite have the right words. It’s the reasoning behind my talk. I want to talk about accessible unethical technology.

When discussing inclusivity, we often discuss intersectionality.

Intersectionality is a theory introduced by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw where she examined how black women are often let down by discrimination narratives that focus on black men as the victims of race-based discrimination, and white women as the victims of gender-based discrimination. These narratives don’t examine how black women often face discrimination compounded by both race and gender, discrimination unique to black women, and discrimination compounded by other factors such as class, sexual orientation, age and disability.

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw uses intersectionality to describe how overlapping or intersecting social identities, particularly marginalised or minority identities, relate to systems and structures of domination, oppression or discrimination.

We see this in accessibility and inclusivity when we understand that a disabled person frequently has more than one impairment that might impact their use of technology. The impairments reported by disabled people in the UK in the year 2017-2018 shows that many disabled people in the UK have more than one impairment that affected them in the last year.

And those impairments also intersects with a person’s race, class, wealth, job, and so many other factors. For example, a disabled person with affordable access to a useful assistive technology will likely have a very different experience from a disabled person who cannot afford the same access.

We rarely discuss is how the ethical considerations of a product, project or business also intersect with inclusivity.

When the technology you use is a lifeline to access, you are impacted more severely by its unethical factors.

Last year, Dr Frances Ryan covered this in her article, ‘The missing link: why disabled people can’t afford to #DeleteFacebook’. After the Cambridge Analytica scandal was uncovered, many people started encouraging each other to #DeleteFacebook.

Dr Frances Ryan pointed out “I can’t help but wonder if only privileged people can afford to take a position of social media puritanism. For many, particularly people from marginalised groups, social media is a lifeline – a bridge to a new community, a route to employment, a way to tackle isolation.”

This is also echoed in that paper I mentioned earlier, by Jan Fernback and Gwen Shaffer:

“First, economically disadvantaged individuals, Hispanics, and African Americans are significantly more likely to rely on phones to access the internet, compared to wealthier, white Americans. Similarly, people of color are heavier users of social media apps compared to white Americans.”…

“Second, mobile internet use, mobile apps, and cell phones themselves leak significantly more device-specific data compared to accessing websites on a computer.”

”In light of these combined realities, we wanted to examine the kinds of online privacy tradeoffs that disproportionately impact cell mostly internet users and, by extension, economically disadvantaged Americans and people of color.”

And what they found speaks to incredible inequality:

Speaking about this paper, Gwen Schaffer explained

“All individuals are vulnerable to security breaches, identity fraud, system errors, and hacking. But economically disadvantaged individuals who rely exclusively on their mobile phones to access the internet are disproportionately exploited…”

“Unfortunately, members of disadvantaged populations are frequent targets of data profiling by retailers hoping to sell them cheap merchandise or bait them into taking out subprime loans.”

“They may be charged higher insurance premiums or find their job applications rejected. Ultimately, the inequities they experience off-line are compounded by online privacy challenges.”

But many (and I think a lot of us can identify with this feeling!), felt resigned to trading their privacy for access to the Internet:

“Study participants, largely, seemed resigned to their status as having little power and minimal social capital.”

And I believe that these inequalities are likely to intersect with disabled people’s lives. Particularly because disabled people already have less access to the Internet…

If we read the UK’s Office for National Statistics Internet Use report for 2019, the number of disabled adults using the internet has risen. However, there’s still a whopping 17% difference between disabled adults and non-disabled adults.

“In 2019, the proportion of recent internet users was lower for adults who were disabled (78%) compared with those who were not disabled (95%).”

If we briefly return to the topic of privacy policies, I noted that the reading level required for the average privacy policy was higher than the education afforded most Americans.

In fact, the report suggested 498/500 of the privacy policies examined required more than 14 years of education to understand…

What they failed to note was how that might be significantly harder to access for those with difficulties reading.

This brings me to the intersection of privacy and access.

It’s what I really wondered about when I read the results of WebAIM’s 8th Screenreader User Survey.

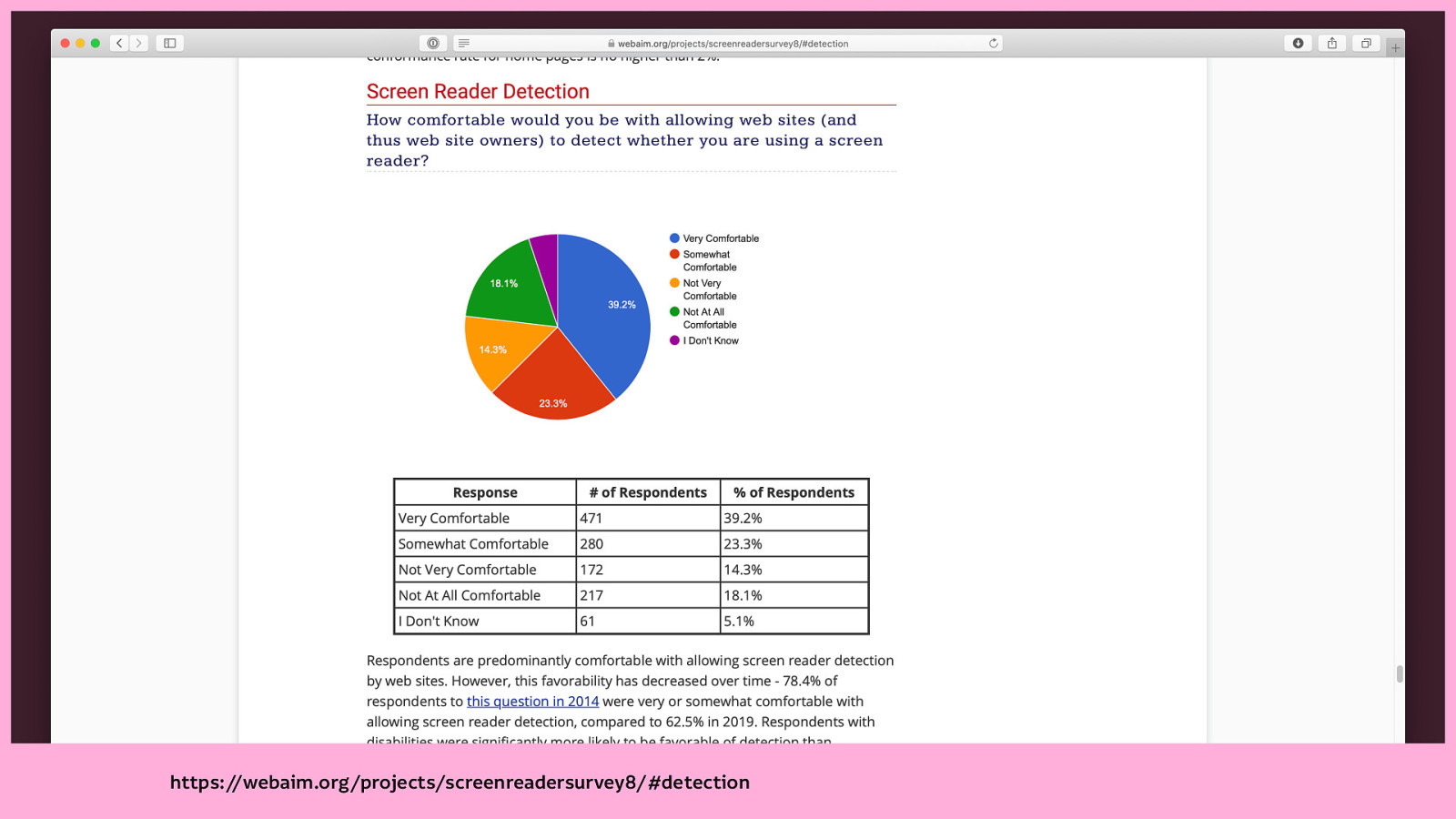

The survey featured the question, “How comfortable would you be with allowing web sites (and thus web site owners) to detect whether you are using a screen reader?”

Responses were 62.5% “very or somewhat comfortable” with allowing screen reader detection, with respondents with disabilities being significantly more likely to be favourable of detection than respondents without disabilities.

The report summarises: > “These responses clearly indicate that the majority of users are comfortable with revealing their usage of assistive technologies, especially if it results in a more accessible experience.”

The report also points to Marco Zehe’s blog post on that very question from 2014, where he discusses problems that could (or are even likely) to arise if a website could detect whether a visitor was using a screenreader. It’s a question that has come up again this year with Apple briefly enabling assistive technology detection in iOS Safari.

Léonie Watson lays out the case against screen reader detection very clearly in the same year including (and I paraphrase badly here):

Like the detection of any personal information, it’s an invasion of privacy. The decision about what you choose to share is taken away from you. The consequences are then further decisions are made on your behalf.

Often when I discuss sharing personal information with people, they only think about the value of a specific (sometimes sensitive) data point, and not the implications of sharing that data point with others.

Marco goes into this in detail in his blog post, discussing that one data point of him using a screenreader:

“For one, letting a website know you’re using a screen reader means running around the web waving a red flag that shouts “here, I’m visually impaired or blind!” at anyone who is willing to look…”

“It would take away the one place where we as blind people can be relatively undetected without our white cane or guide dog screaming at everybody around us that we’re blind or visually impaired, and therefore giving others a chance to treat us like true equals.”

“Because let’s face it, the vast majority of non-disabled people are apprehensive in one way or another when encountering a person with a disability.”

Curious about the feelings of people who don’t work in tech, I asked my brother Sam. (A lazy focus group of one.) He’s a bit biased because he’s my brother, has some knowledge of tech, and has to put up with me going on about privacy all the time (and he says that has affected how he uses the web.)

Sam has cerebral palsy and learning difficulties, uses a screen reader occasionally and uses dictation software 90% of the time. As a person with a neurological condition that is visible in his physicality, he gets Marco’s perspective, he’s frustrated by how people treat him when they know he’s disabled.

Still, Sam has the same feelings as many of those screen reader users responding to the survey:

“I don’t mind if the platforms know I’m disabled, if they provide me with better access. Though I’d be bothered if they made it obvious to other users of the platform…”

Sam, and the 62.5% of screen reader users should be allowed to make this choice. As long as it is a real choice. As long as we know who is allowed access to our information, and how much, and how often, and for how long, and when.

Like so many issues we have with technology, what we’re dealing with are the underlying social and systemic issues. As technologists, we often can’t help ourselves trying to fix or smooth over problems with technology. But technology can’t fix issues of domination, oppression or discrimination.

But it can make those issues worse. We can (and do) amplify and speed up systemic issues with technology.

Mike Ananny made this point recently in an article about tech platforms. We still seem to operate with the notion that online life is somehow a different life, detached from our everyday existence.

And tech platforms often take advantage of that notion by suggesting that if we don’t like “technology” (because they also imply that their approach is the one true inevitable way to build tech), we can just log out, log off, and be mindful or some other shit instead.

People with this mindset often show how shallow they are by saying “if you don’t like technology, you don’t have to use it…”

But there’s a reason we can’t escape technology:

“Platforms are societies of intertwined people and machines. There is no such thing as “online life” versus “real life.” We give massive ground if we pretend that these companies are simply having an “effect” or “impact” on some separate society.”—Mike Ananny

Which brings me to another issue rife in technology today. Given that I’m a non-disabled person currently talking about accessibility and inclusivity, I think it’s worth me also mentioning technology colonialism.

First explaining what colonialism is…

“European colonialism was spurred by an interest in trade with foreign nations. This involved the exchange of materials and products between the colonial powers and foreign nations.”

“Colonial powers always saw themselves as superiors over the native people whose culture was rarely recognized or respected. The colonizers saw economic value in these foreign relations, but it was always viewed as a transaction based on inequality.”…

And then comparing it to what we so often do in technology:

“Technology companies continue this same philosophy in how they present their own products. These products are almost always designed by white men for a global audience with little understanding of the diverse interests of end users.”

Can you tell why I think technology colonialism is incredibly relevant to inclusivity?

We don’t speak to users. Instead, we use analytics to design interfaces for people we’ll never try to speak to, or ask whether they even wanted to use our tech in the first place. We’ll assume we know best because we are the experts, and they are “just users.” We don’t have diverse teams, we barely even try to involve people with needs different from our own. How often do we try to design accessible interfaces without actually involving anyone who uses assistive technology?

It’s the reason disabled activists and anti-racism activists both say “Nothing about us without us.” Because assuming you know what’s best for people with different needs from your own usually results in an incorrect (and too often) patronising solution.

All this talk of being colonial, it’s important for me to acknowledge my own position as a non-disabled person advocating for inclusivity and accessibility. I believe we have to hold our communities to account without centring ourselves.

I don’t know what’s best for anyone, but when I learn what’s harmful, I’m going to pay attention and share what I learn. Accessibility is not charity or kindness, it’s a responsibility.

We not only have a responsibility to design more inclusive and accessible technology, but to consider the impact our design has outside of its immediate interface.

Making our technology inclusive and accessible is not enough if the driving forces behind that technology are unethical.

We shouldn’t be grateful for the accessibility of unethical products.

Accessibility is only inclusive if it respects all the rights of a person.

As the people advocating for change, we can’t exactly go around telling people to stop using this technology unless there are real, ethical alternatives.

That’s where you and me come in. As people who work in technology, and who create technology, we have far more power for change. We can encourage more ethical practice. We can build alternatives.

How do we build ethical technology?

As an antidote to big tech, we need to build small technology.

Everyday tools for everyday people designed to increase human welfare, not corporate profits.

Yeah, sure it’s a lofty goal, but there are practical ways to approach it.

Let’s make a start with some approaches. Best practices, if you will.

Plenty of privacy-respecting tools exist for nerds to protect themselves (I use some of them.) But we mustn’t make protecting ourselves a privilege only available to those who have the knowledge, time and money.

It’s why we must make easy-to-use technology that is

We must ensure people have equal rights and access to the tools we build and the communities who build them, with a particular focus on including people from traditionally marginalised groups.

Free and open technology (a lot of those nerd tools) are particularly terrible at this, not building accessible technology, and often surrounding themselves with toxic communities.

Our teams must reflect the intended audience of our technology.

If we can’t build teams like this (some of us work in small teams or as individuals), we must ensure people with different needs can take what we make and specialise it for their needs. We can build upon the best practices and shared experiences of others, but we should not be making assumptions about what is suitable for an audience we are not a part of.

We’ve got to stop our infatuation with growth and greed. Focus on building personal technology for everyday people, not spending all our focus, experience, and money on tools for startups and enterprises.

Next up, the architecture of the technology.

This bears repeating: Privacy is the ability to choose what you want to share with others, and what you want to keep to yourself.

Make your technology functional without personal information.

Consent: Allow people to share their information for relevant functionality only with their explicit consent.

Consent: When obtaining consent, tell the person what you are going to do with their information, who will have access to it, and how long you will keep that information stored. (This has recently become established as a requirement under the GDPR.)

Consent: Write easy-to-understand privacy policies. Don’t just copy and paste them from other sites (they probably copy-pasted them in the first place!) Ensure it’s up-to-date with every update to your technology.

Consent: Don’t use third-party consent frameworks. Most of these aren’t GDPR-compliant, they’re awful experiences for your visitors, and they’re likely to just get you into legal trouble.

Third-party services: Don’t use third-party services if you can avoid them. (As they present a risk to you and your users.)

Third-party services: Make it your responsibility to know what they’re doing with your users’ information.

If you do use third-party services, make it your responsibility to know their privacy policies, what information they are collecting, and what they are doing with that information.

Third-party services: Self-host all the things.

If you use third-party scripts, delivery networks, videos, images and fonts, self-host them wherever possible. Ask the providers if it’s unclear whether they provide a self-hosted option

And it’s probably worth mentioning a little bit of social media etiquette:

If you know how, strip the tracking identifiers and Google amp junk from URLs before you share them. Friends don’t let corporations invade their friends’ privacy.

Social media etiquette: If you feel you need a presence social media or blogging platforms, don’t make it the only option. Post to your own site first, then mirror those posts on third-party platforms for the exposure you desire.

Zero-knowledge tools have no knowledge of your information. The technology may store a person’s information, but the people who make or host the tools cannot access that information if they wanted to.

Zero-knowledge: Keep a person’s information on their device where possible.

Zero-knowledge: If a person’s information needs to be synced to another device, ensure that information is end-to-end encrypted, with only that person having access to decrypt it.

Peer-to-peer systems enable people to connect directly with one another without a person (usually a corporation or a government) in the middle. Often this means communicating device to device without a server in the middle.

Interoperable systems can talk to one another using well-established protocols, such as web standards. (Standards don’t always mean best practice, but that’s a discussion for another time…) Make it easy for a person to export personal information from your technology into another platform. (This is also required by GDPR.)

Interoperable: Make it easy for a person to export their information from your technology into another platform. (This is also required by GDPR.)

And we also have to take care with how we share our technology, and how we sustain its existence. Make it share alike.

Cultivate a healthy commons by using licences that allow others to build upon, and contribute back to your work. Don’t allow big tech to come along, make use of it and shut it off. (That’s what the MIT licence allows!)

And we also have to take care with how we share our technology, and how we sustain its existence. Make it non-commercial.

Non-commercial: Build stayups, not startups.

My partner at Small Technology Foundation, Aral Balkan, coined the term stayups for the anti-startup. We don’t need more tech companies aiming to fail fast or be sold as quickly as possible. We need long-term sustainable technology.

Non-commercial: Build not-for-profit technology.

If we are building sustainable technology for everyday people, we need a compatible funding model, not venture capital or equity-based investment.

Are you asking how can I do any of this?

It may feel difficult or even impossible to build small technology with your current employer or organisation. It probably is! But there are steps we can take to give ourselves the opportunity to build more ethical technology.

If you have the time, make a personal website, practice small technology on your own projects.

Use small technology as a criteria when you’re looking for your next job. You don’t have to be at your current job forever.

Developing accessibility best practices is always a good thing. If you’re currently making unethical technology accessible, that’s fine. At least you can use those skills to make accessible ethical technology in the future.

So building small technology… who builds it?

These are all comments I’ve heard from people aiming to demean our work. I’ve been speaking about this for around seven years. I’ve been heckled by a loyal Google employee, I’ve been called a tinfoil-hatwearing ranter by a Facebook employee. I’ve had people tell me there just isn’t any other way, that I’m just trying to impede the “natural progress” of technology.

As Rose Eveleth wrote in a recent article on Vox, about that assertion that technology is just following its natural progress:

“The assertion that technology companies can’t possibly be shaped or restrained with the public’s interest in mind is to argue that they are fundamentally different from any other industry. They’re not.”

We can’t keep making poor excuses for bad practices.

We must consider who we are implicitly endorsing when we recommend their work and their products.

And, I’m sorry, I don’t give a jot about all the cool shiz coming out of unethical companies. You are not examples to be held above others. Your work is hurting our world, not contributing to it.

Our whole approach matters. It’s not just about how we build technology, but our approach to being a part of communities that create technology.

You might be thinking “but I’m just one person.”

But we are an industry, we are communities, we are organisations, we are groups made up of many persons. And if more of us made an effort, we could have a huge impact.

We have to remember that we are more than just the organisation we work for. If you work for a big corporation that does unethical things, you probably didn’t make the decision to do that bad thing. But I think the time has come that we can no longer unquestioningly defend our employers.

We need to use our social capital, we need to be the change we want to exist.

But how? I have some ideas…

We’ve got to be comfortable being different, we can’t just follow other people’s leads when those other people aren’t being good leaders. Don’t look to heroes who can let you down, don’t be loyal to big corporations who don’t care anything for you.

Be the advisor. Do the research on inclusive, ethical technology, make recommendations to others. Make it harder for them to make excuses. (You’re here, you’re doing it already!)

Be the advocate. Marginalised folks shouldn’t have to risk themselves to make change. Advocate for others. Advocate for the underrepresented.

Question those defaults. Ask why was it been chosen to be built that way in the first place? Try asking a start-up how it makes its money!

When the advocacy isn’t getting you far enough, use your expertise to prevent unethical things from happening on your watch. You don’t have to deploy a website, and other people might not know how to deploy that website.

Be difficult. Be the person who is known for always bringing up the issue. Embrace the awkwardness that comes with your power. Call out questionable behaviour.

Don’t let anybody tell you that standing up for the needs of yourself, and others, is unprofessional. Don’t let people tell you to be quiet. Or that you’ll get things done if you’re a bit nicer.

Be the supporter. If you are not comfortable speaking up for yourself, at least be there for those that do. Remember silence is complicity.

Speaking up is risky. We’re often fighting entities far bigger than ourselves. We have our lives, the way we make money at risk…

But letting technology continue this way is riskier.

Someone came up to me after I gave a talk a couple of months ago, and referred to me as “the woman who comes and tells people to eat their vegetables.” But I am not your mother!

I’m just here because I want to tell you that we deserve better.