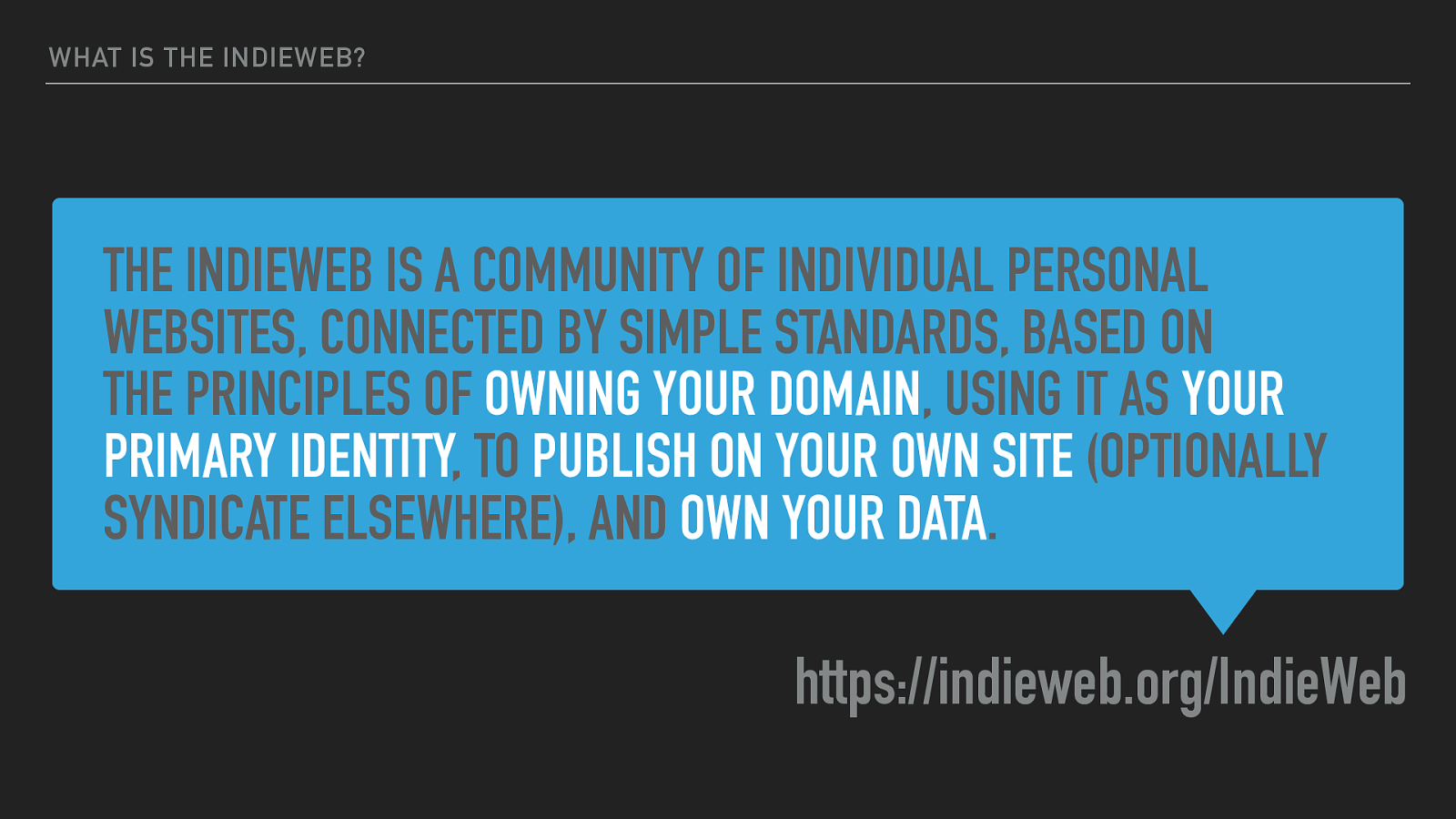

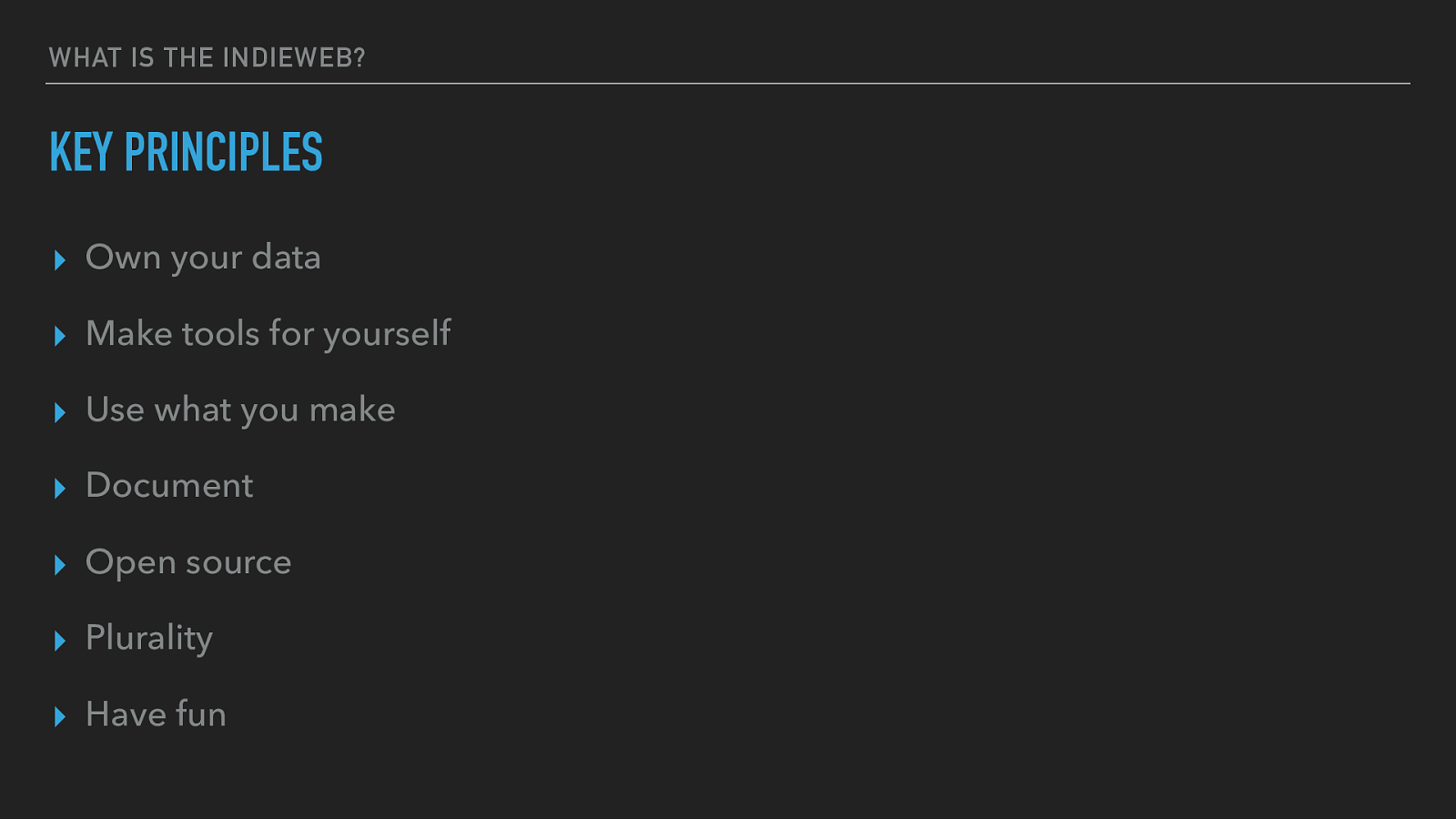

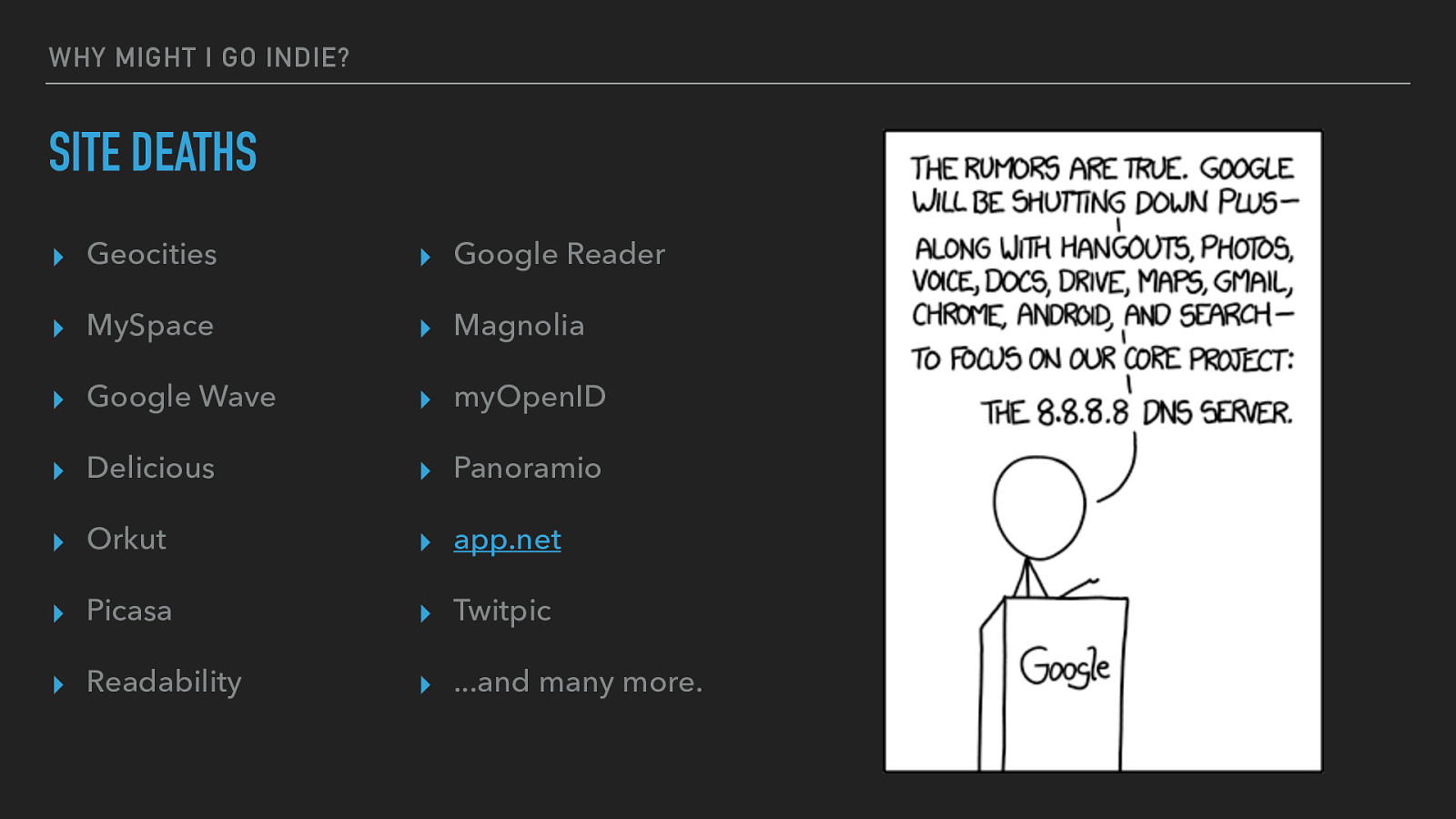

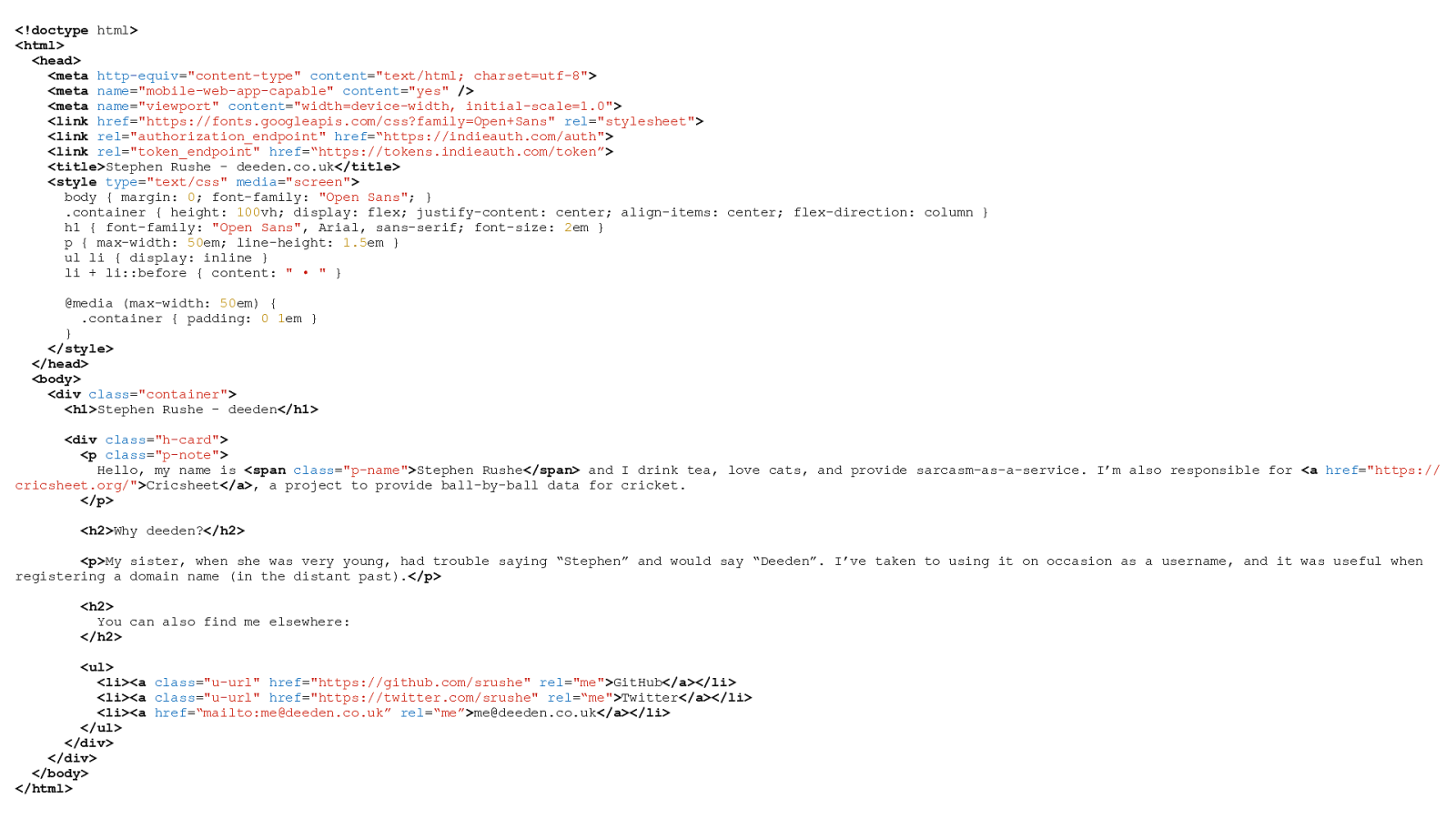

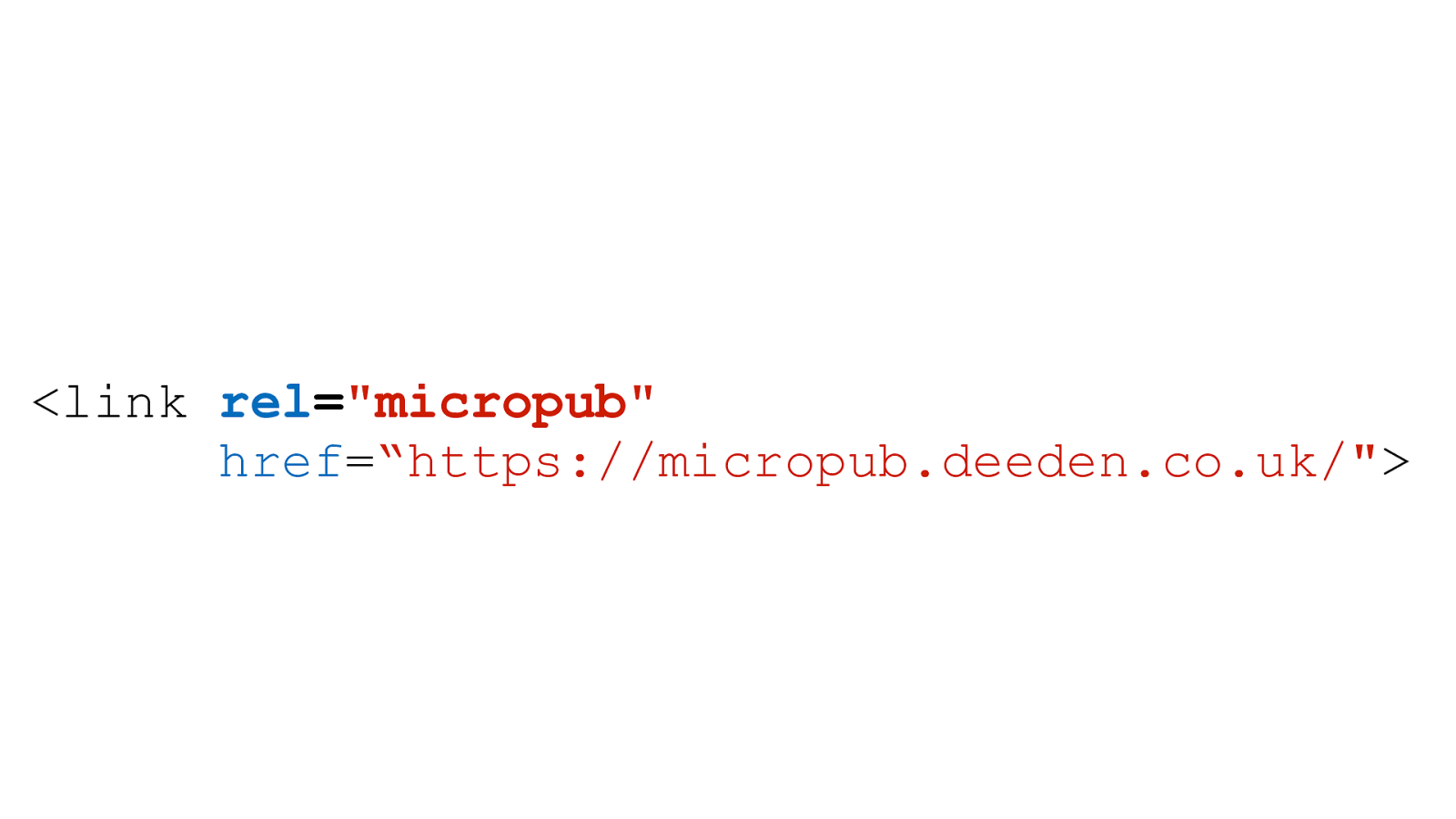

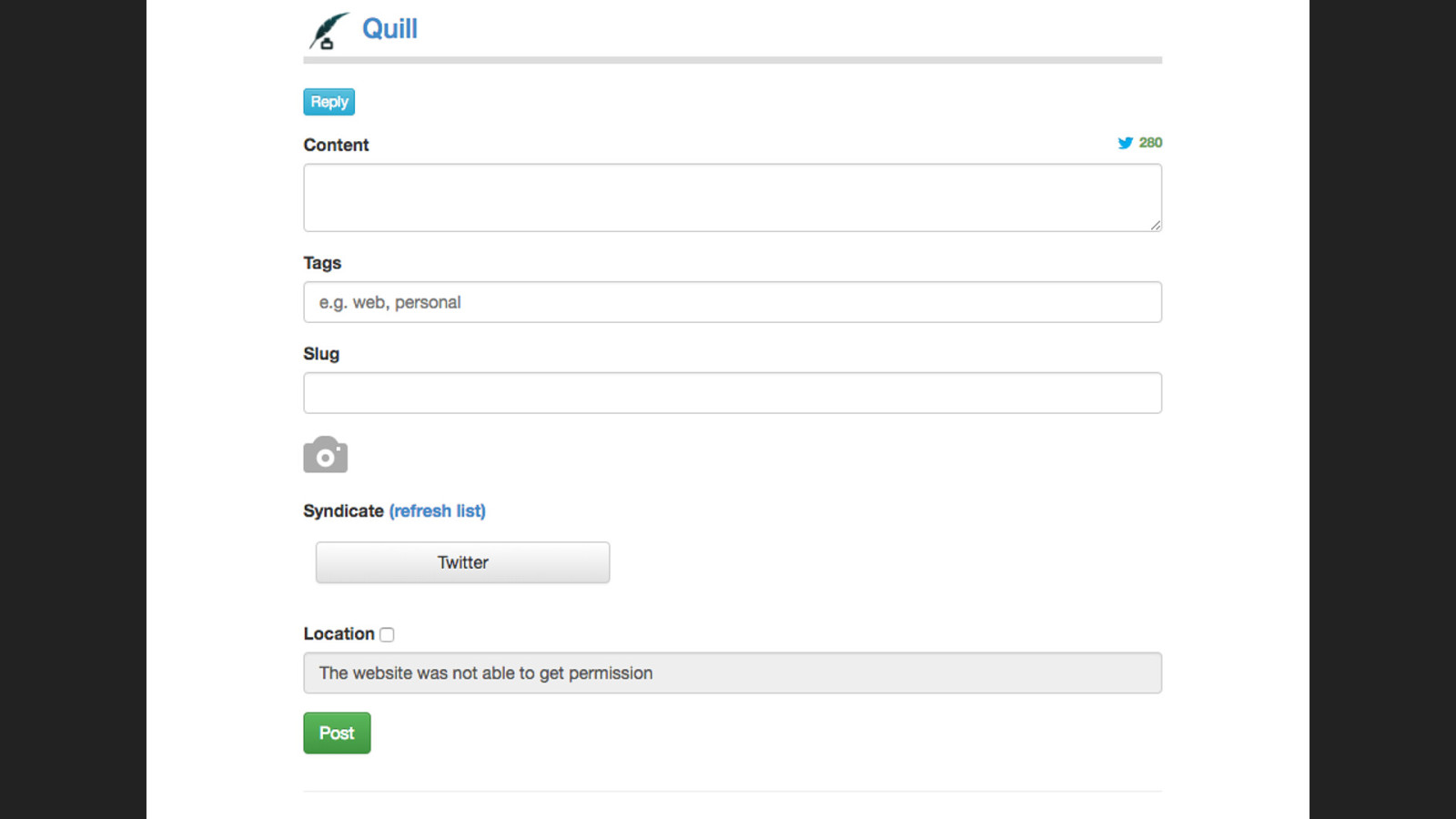

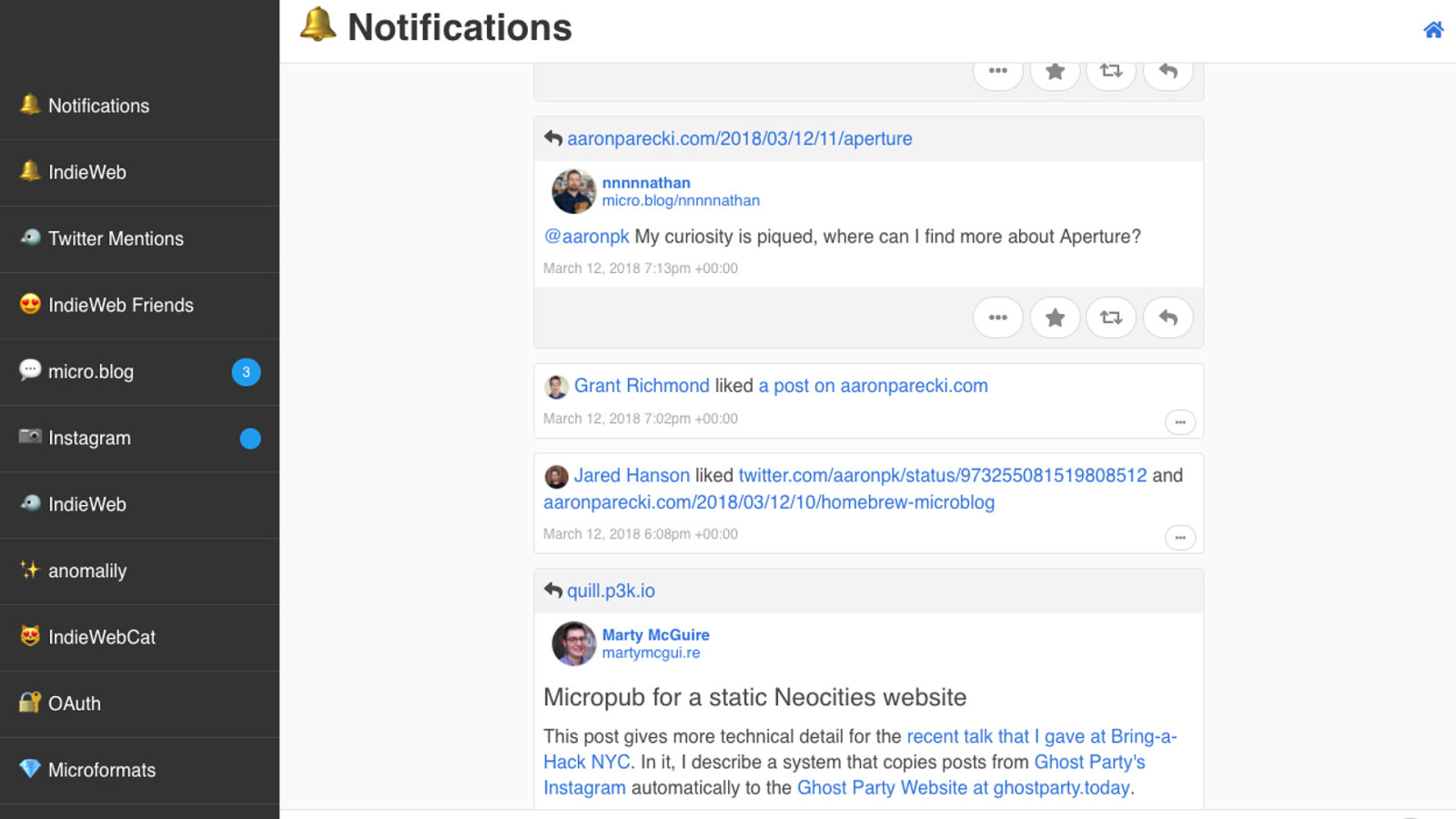

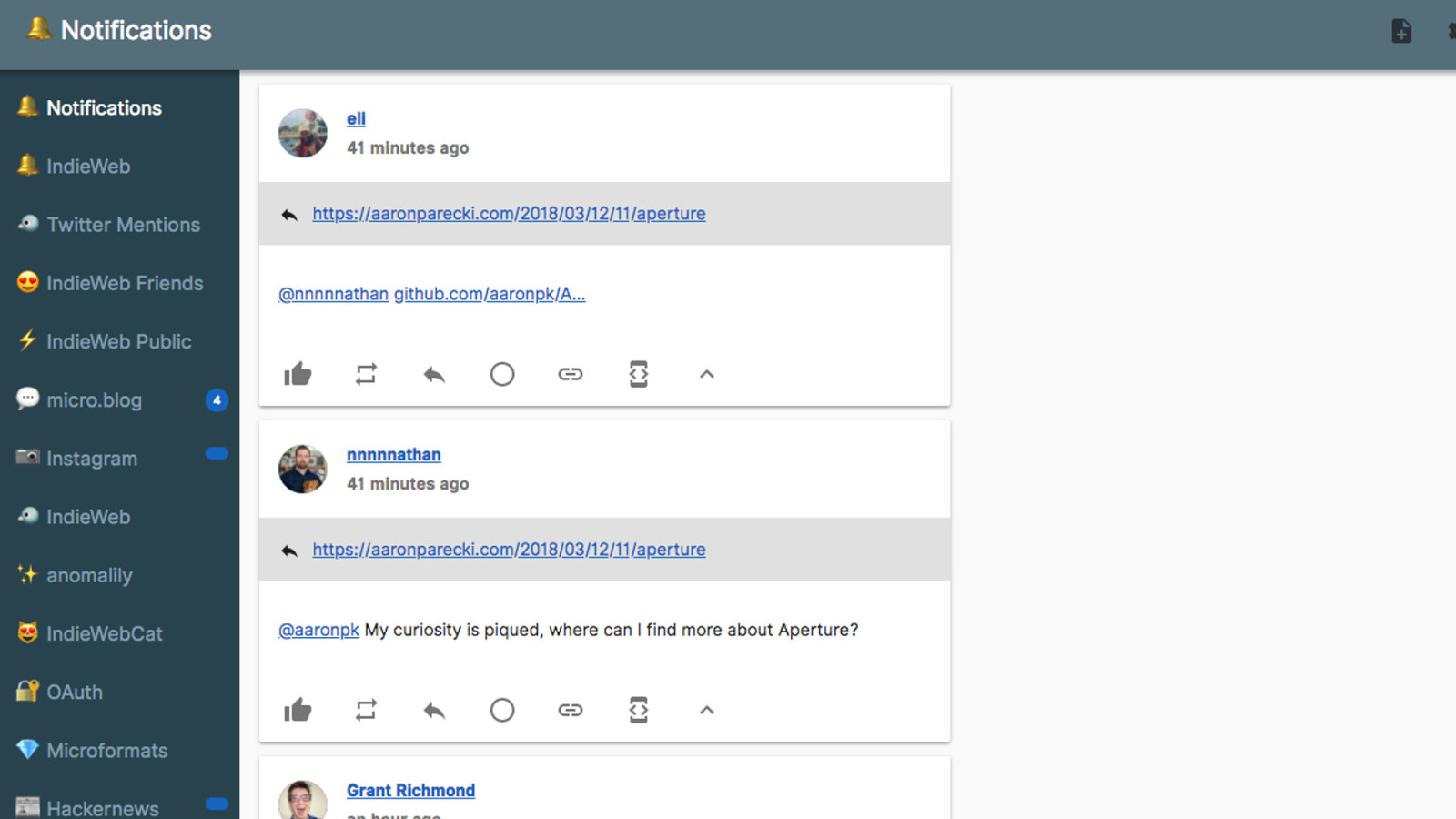

Own your data: Post on your own site (rather than on Medium, Twitter etc). You can still post to those other sites, but post to your site too/first.

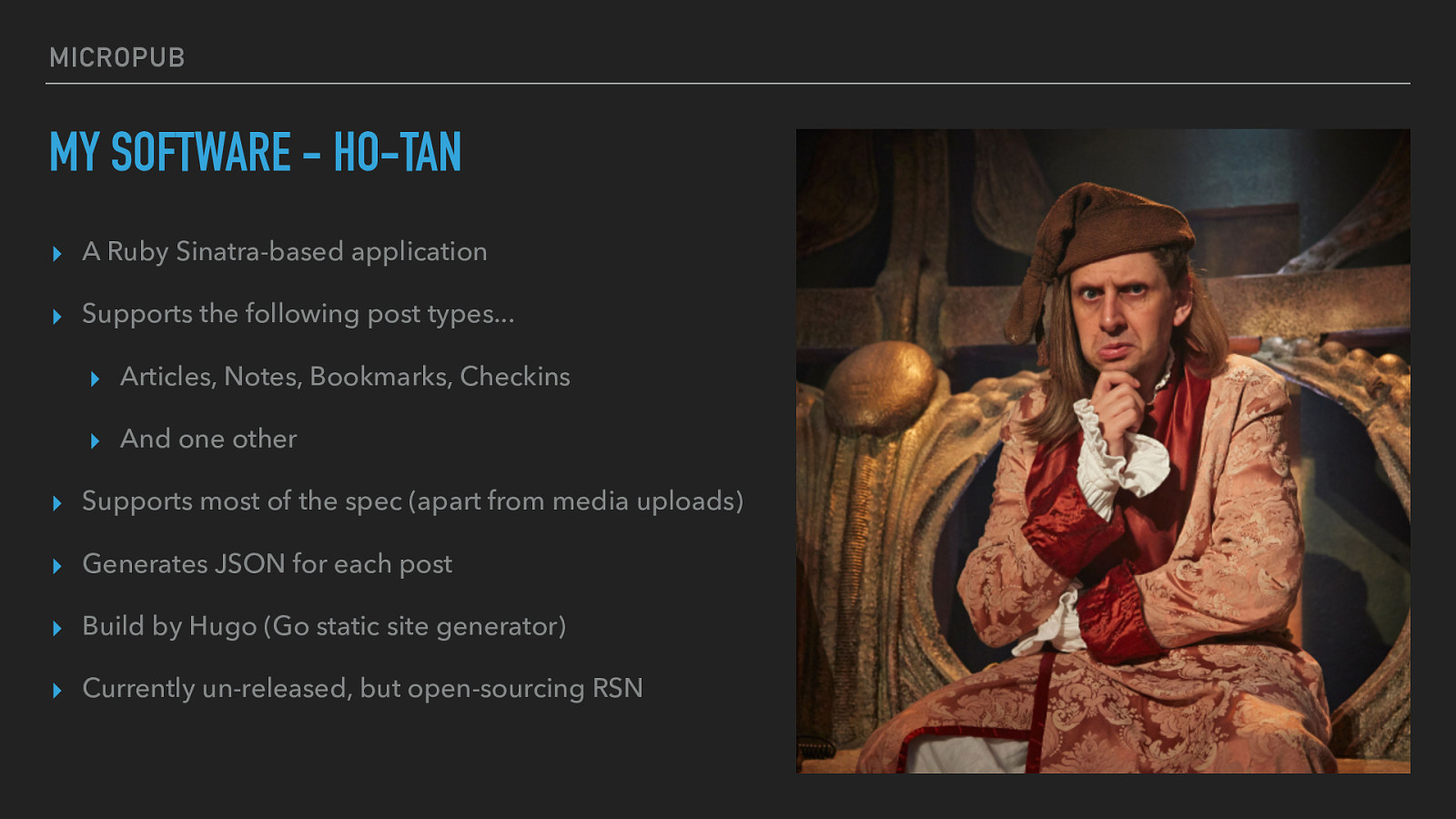

Make tools for yourself: Don't write code for a hypothetical user. Write for your own needs. And make it compatible with others. Other users can come later.

Use what you make: Use the tools you write. "Using your own creations on your own personal site that you depend on".

Document: "document your processes, ideas, designs and code”.

Open source: Not compulsory, but a good idea, as it let's other get up and running more quickly.

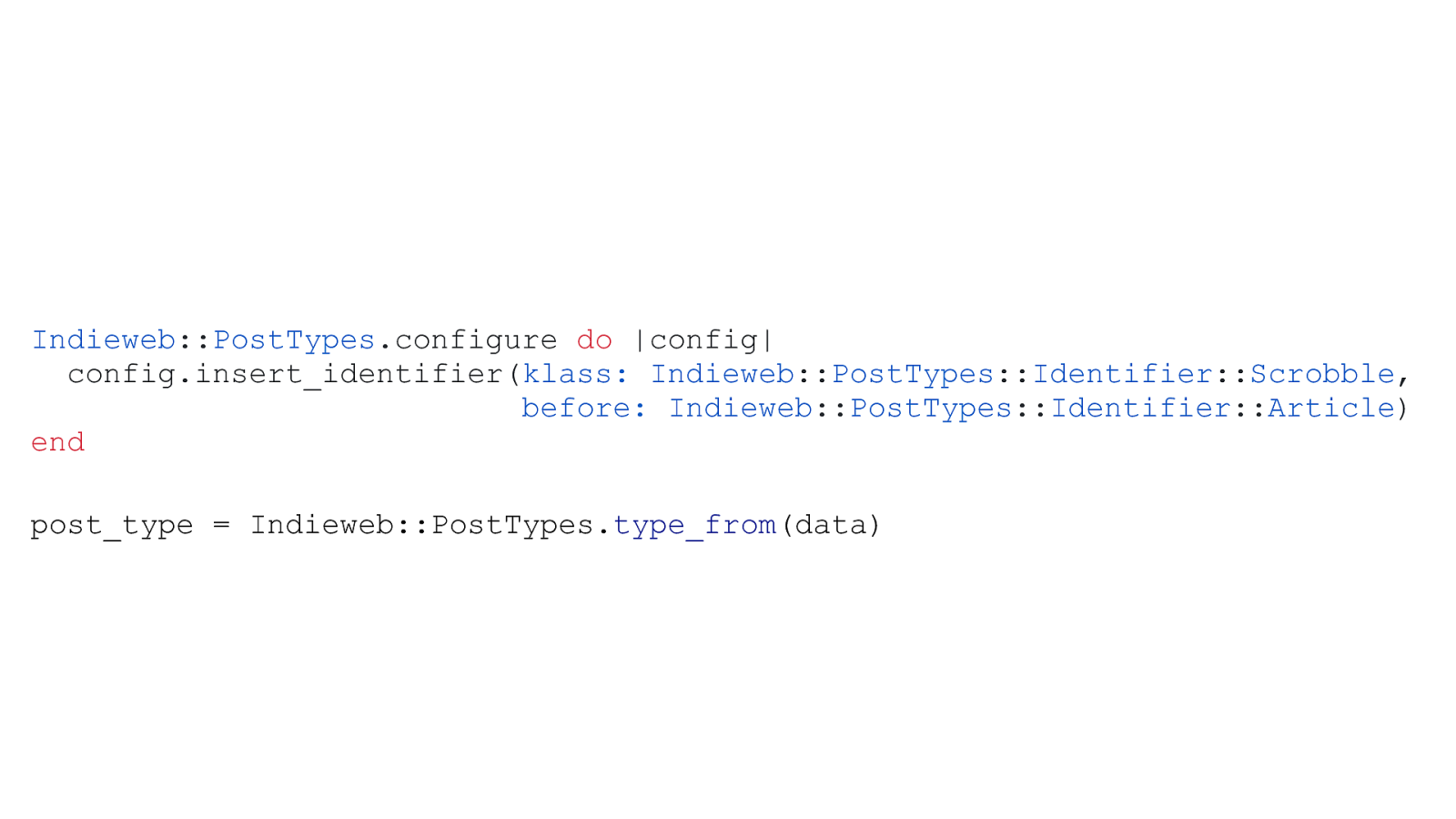

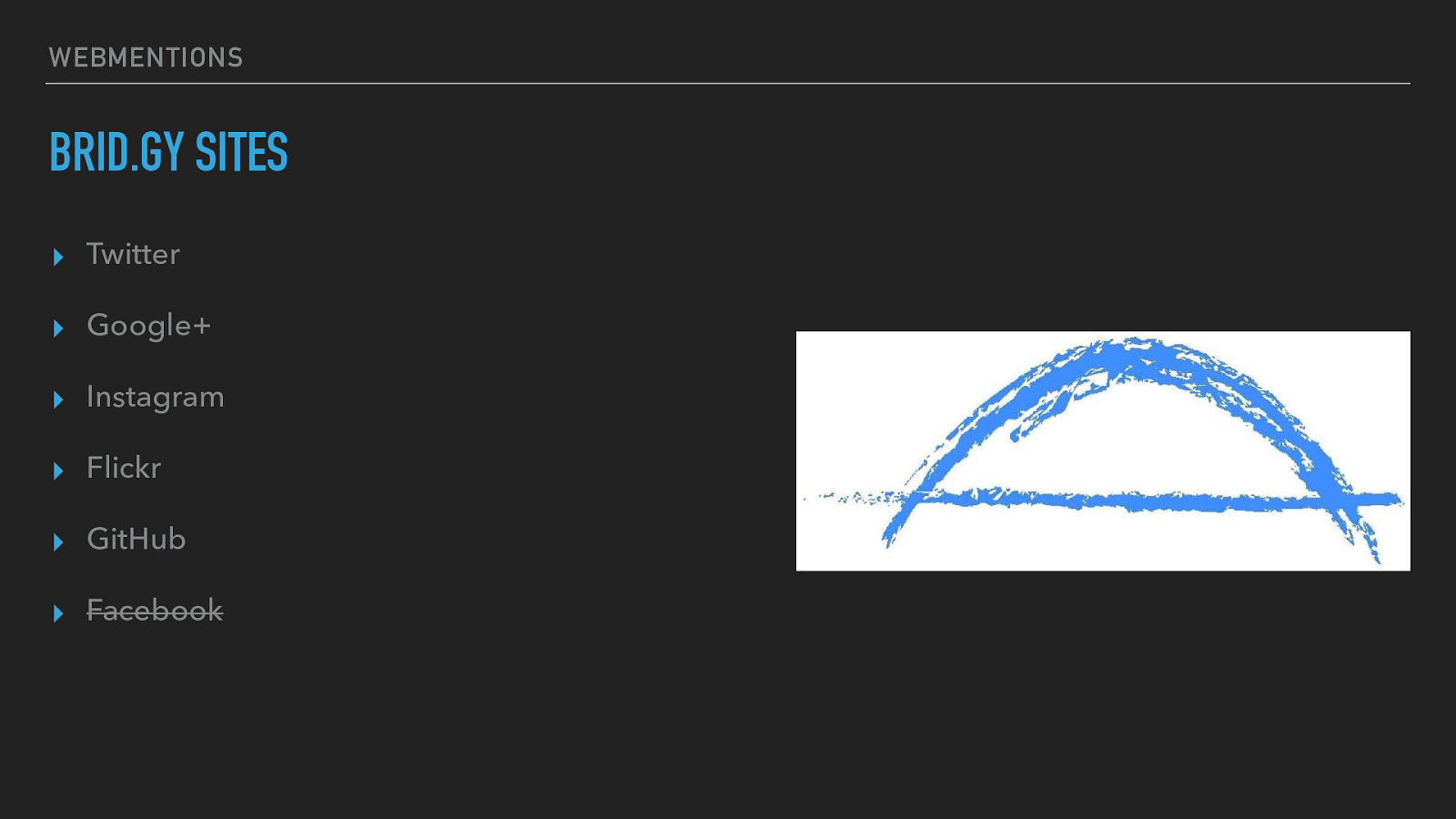

Plurality: Many inter-operable solutions, not the same setup. Build things, and work out how to make them work together, leading to specifications.

Fun: It should be interesting and fun.