Slide 1

The Intersection of Performance & Accessibility

performance.now()

Slide 2

- Hallo everyone!

- My name is Eric, and I’m a Senior Accessibility Designer at GitHub.

- I live in Boston, Massachusetts in the United States, and am a tall white man with black hair and glasses

- I’m wearing a short sleeve button down shirt with a pink brain pattern on it because brains are weird and fun, and this is actually my first time in Amsterdam!

Slide 3

- Before I get into it, I just want to extend my appreciation here

Getting a chance to speak about accessibility outside of accessibility circles is a wonderful opportunity

- I’m thankful to the conference organizers for enabling this, and to you, the audience, for being receptive to it

- There are a lot of parallels between the practices of performance and accessibility, and I hope this talk will help illustrate that

Slide 4

- So, with that said, let’s set the stage

Slide 5

- This is a talk about performance,

- With performance being the manner in which a mechanism behaves

- And with this context established, know that I’ll mainly be talking about the behavior of the mechanisms that power assistive technology

Slide 6

- So, I was conducting an accessibility audit a few years ago

- If you’re not familiar with what an accessibility audit is, know that it is

the process of performing manual and automated checks to see if a digital experience can be operated by assistive technology

- It’s very similar to performance profiling and auditing, and equally as nerdy and detail-oriented

- For accessibility audits, you identify areas where there would be problems or straight-up barriers that would break assistive technology support, thereby preventing someone from using your website or app

- An example of assistive technology that could have its support disrupted would be a screen reader.

- If you’re not familiar, a screen reader is specialized software that parses the contents of the screen, announces that content to the person using it, and lets them take action on it

- And a button that someone is unable to press to save their progress because of how it is coded is an example of an audit issue that affects a screen reader user

- This is a case of accidental exclusion, where someone is prevented from being able to use functionality made available to others, just by virtue of circumstance

Slide 7

- The experience I was auditing was a medical education app used to train caregivers

- It was built using a single page application framework, using Google’s Material Design library to construct the user interface

Slide 8

- When I learned that, I thought,

“Google made it? Oh sweet. I don’t have to worry as much.”

- So I fire up VoiceOver, which is macOS’s built-in screen reader and start testing.

- Things are going pretty well and then

Slide 9

- VoiceOver crashes! It stops speaking!

- I try restarting Safari, I try clearing the cache, I try closing other tabs. Heck, I even try rebooting.

- Same result every time.

- So, I ask my boss what’s going on and he says, “Oh, it’s probably problems with the Accessibility Tree.”

Slide 10

- The what now?

- Before I get more into this, here’s a question for you:

- How do you describe an interface?

- I’m not saying, “Tell me what you see or hear after you turn the computer on.”

- I’m saying how do you speak computer to a computer to tell it what’s present and what state it’s in?

Slide 11

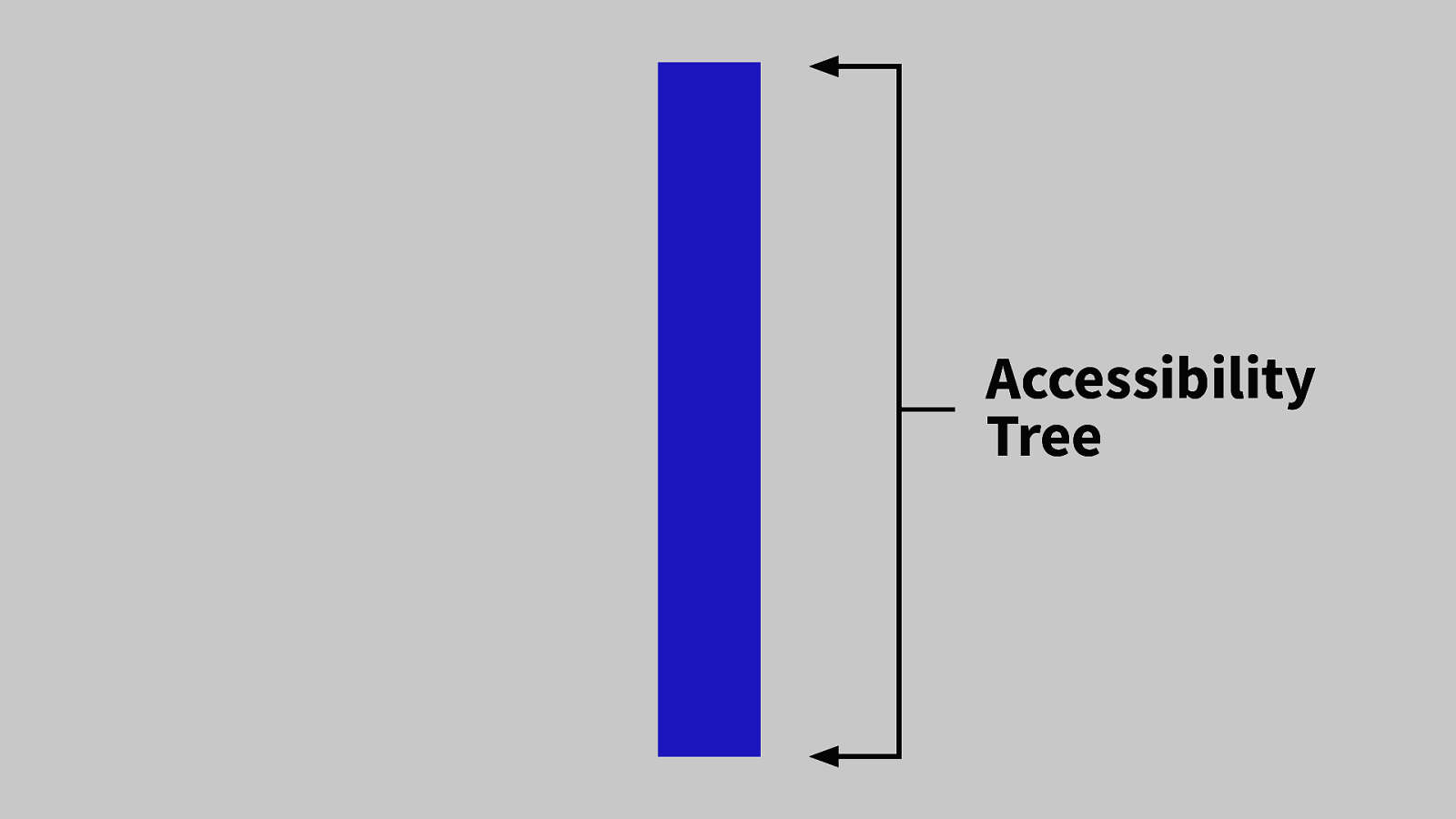

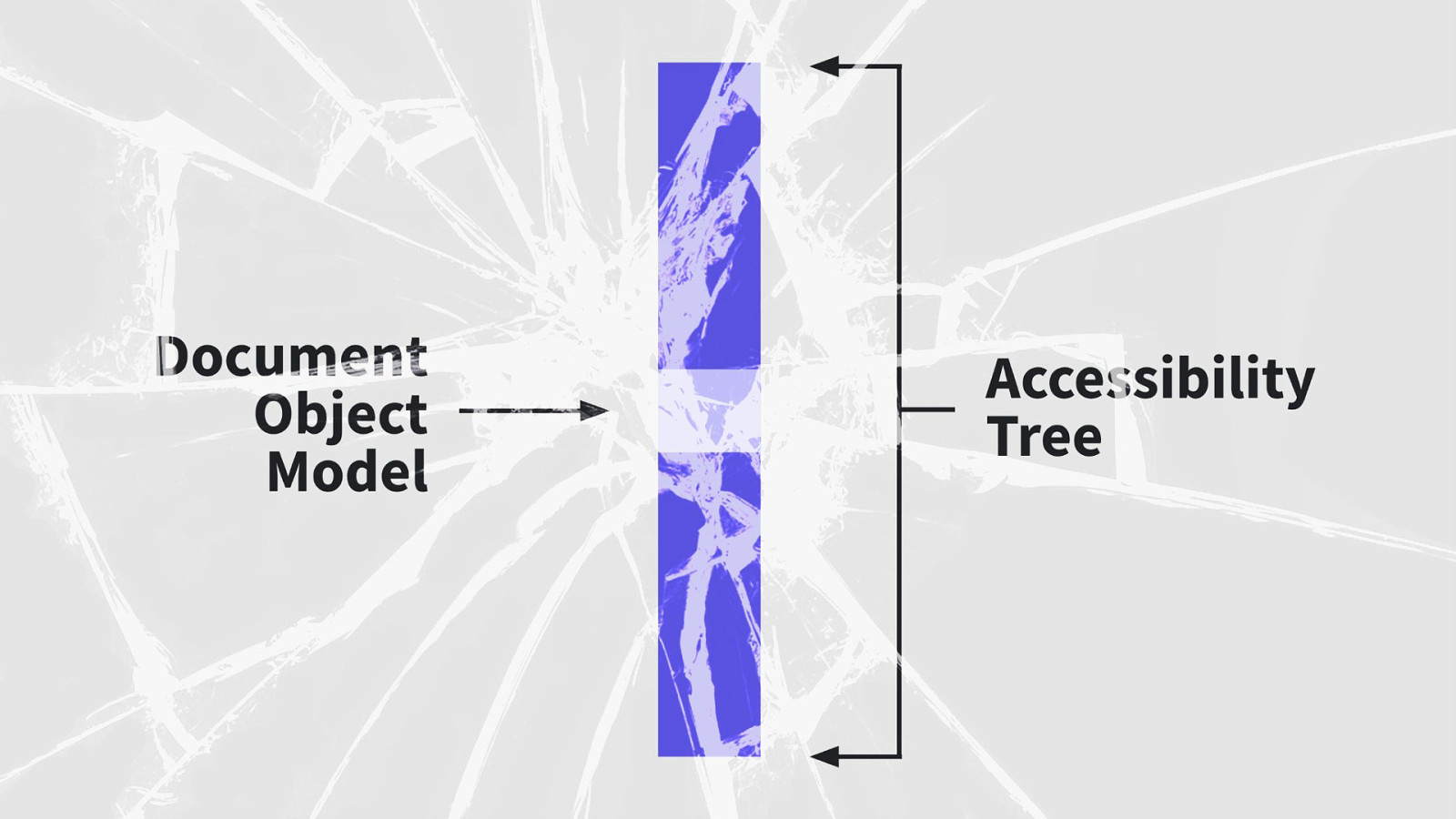

- One way we do that is with the Accessibility Tree

- Fundamentally, the Accessibility Tree is provided by the operating system

- It is a running collection of objects, all the little atomic bits that make up a user interface

- Assistive technology makes use of the Accessibility Tree to read these objects, filter out the irrelevant details, and report the remaining important objects to the user

- Without a functioning Accessibility Tree there is no way to describe the current state of what an interface is

- And consequently no way for some people to be able to use a computer or smartphone

- So suffice it to say it’s a really important piece of technology!

- So, then how do you build an Accessibility Tree? How do we make all these atomic bits of UI work?

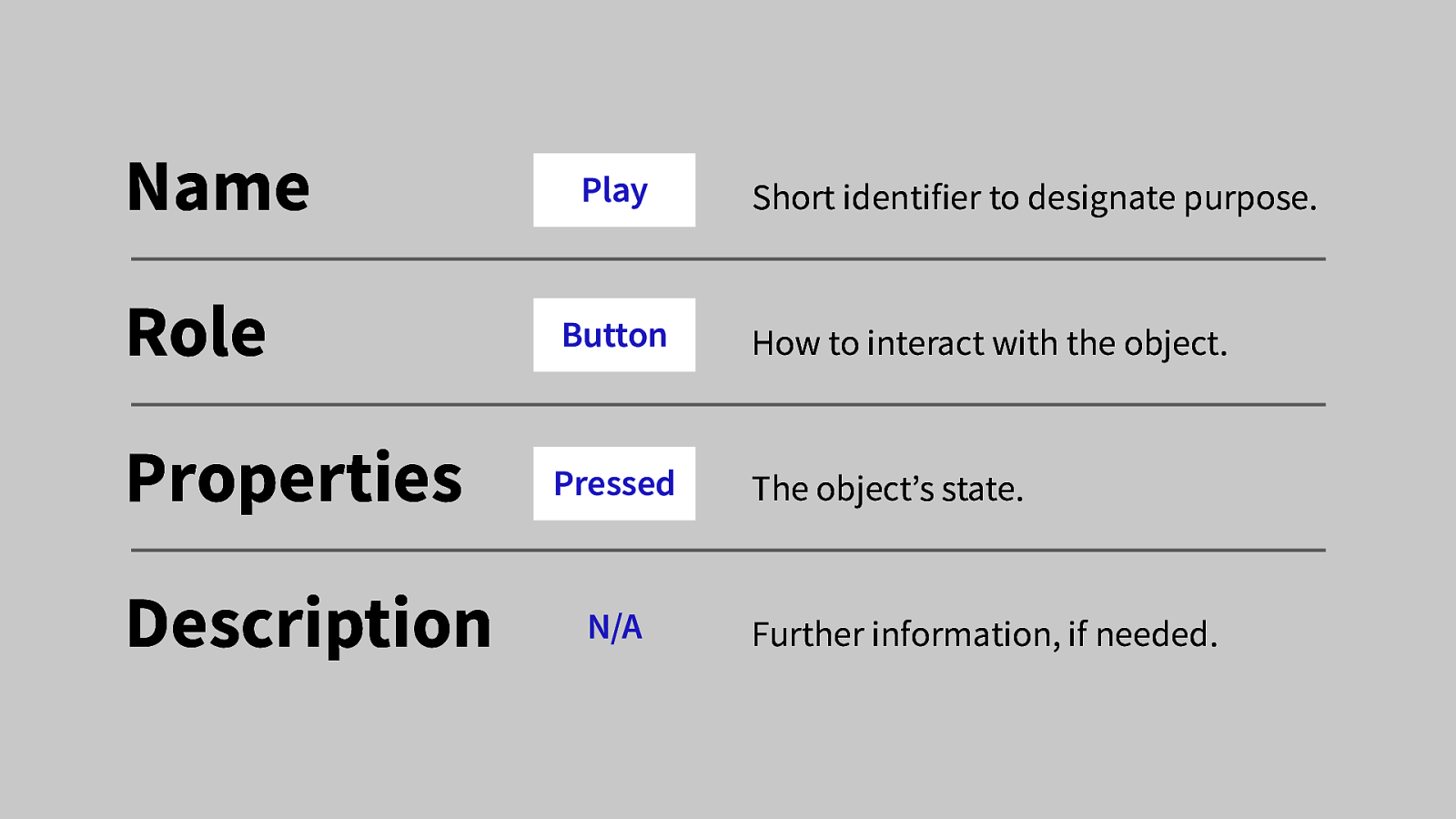

Slide 12

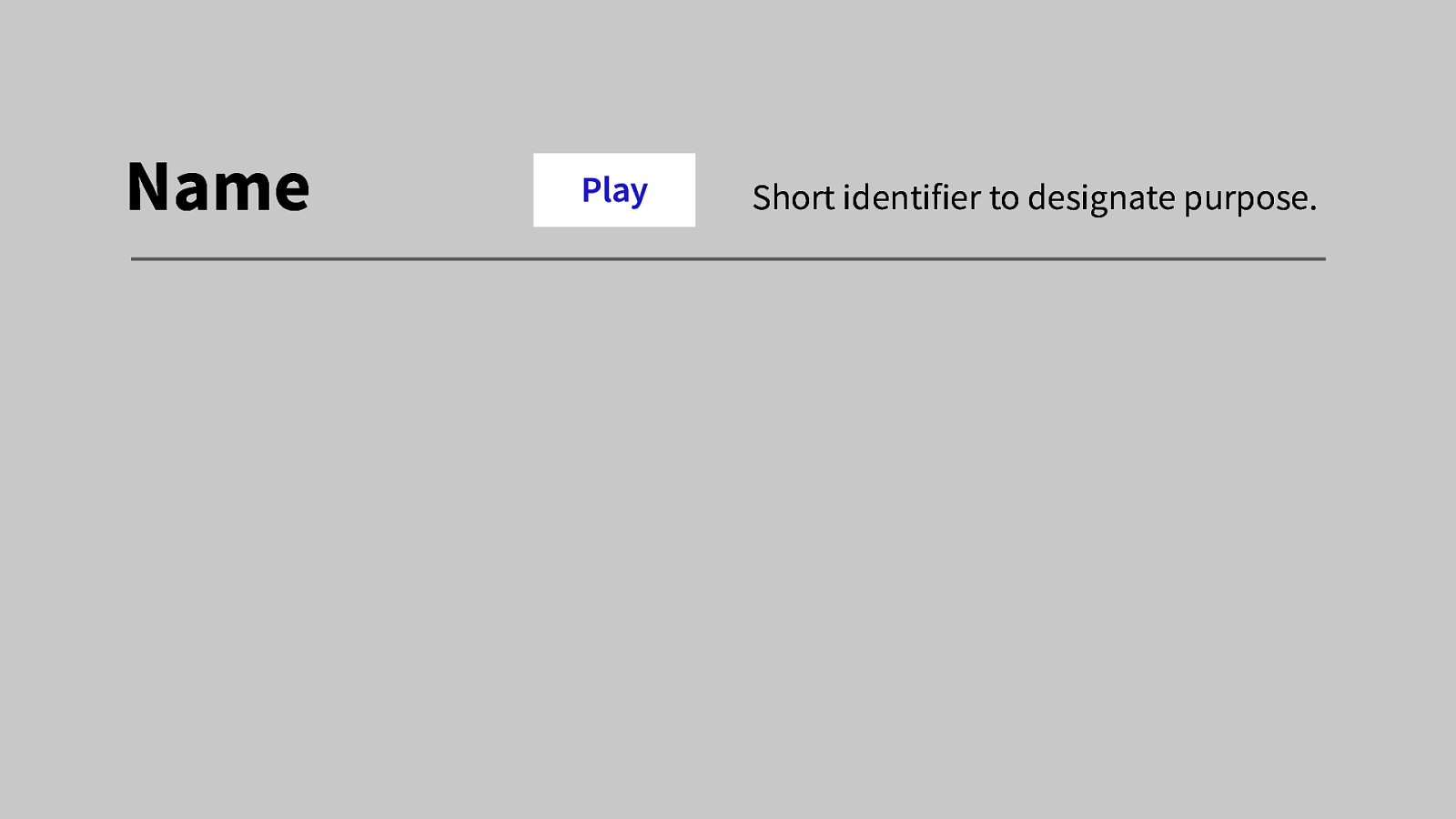

- First, you have to give each individual interactive object in an interface a name,

- Names are a short identifiers used to describe purpose.

Slide 13

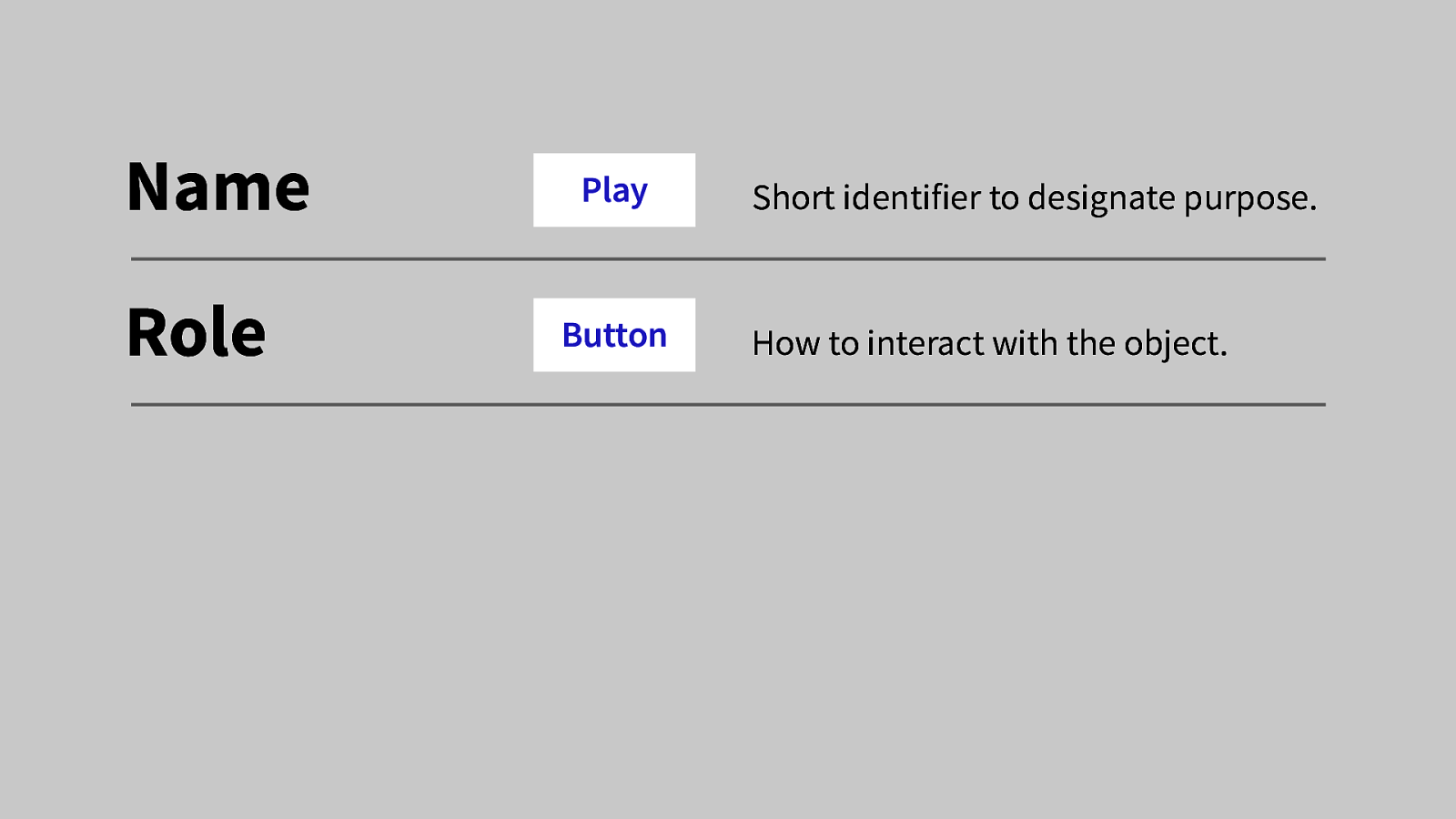

- Then you give it a role.

- Roles are predefined values that tell someone what they can do to the interface object.

- For example, a role of button means that someone can press it to activate some predefined action.

Slide 14

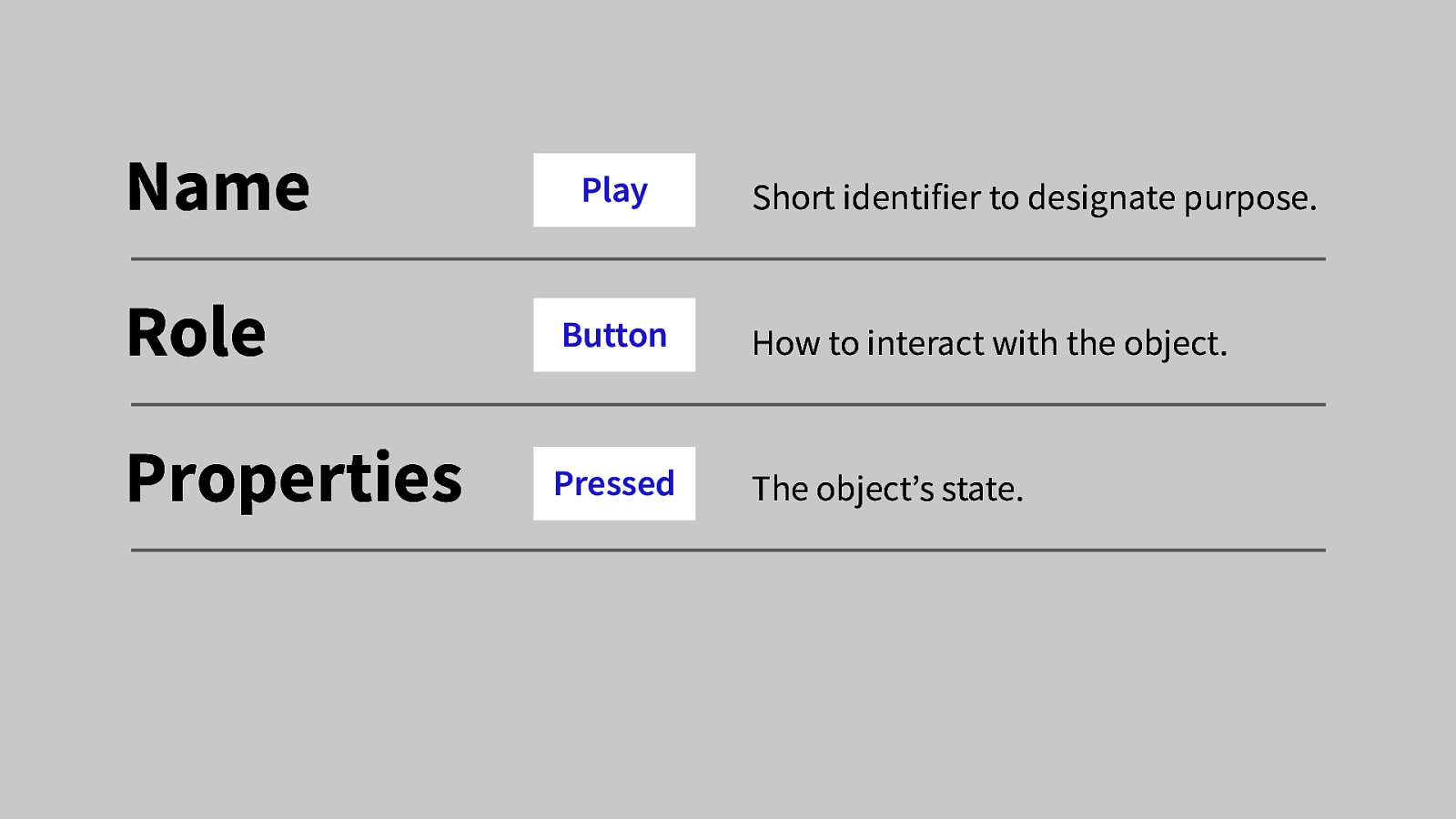

- Then we have properties, which are the attributes of the object.

- Examples of this are its position in an interface, it’s state, or interactions that are allowed.

- For a button, that could mean a toggled state to indicate it is being pressed in, think a play button on a media player

Slide 15

- Finally, we have a description which can provide further information and context about the object, if needed.

- Put these all together and viola! We have an accessible object!

- These accessible objects are then programmatically grouped together to form more complicated interface components

- For example, our play button could be part of a larger media player such as VLC, Spotify, or Apple Music

- So, then how do you build these interface components?

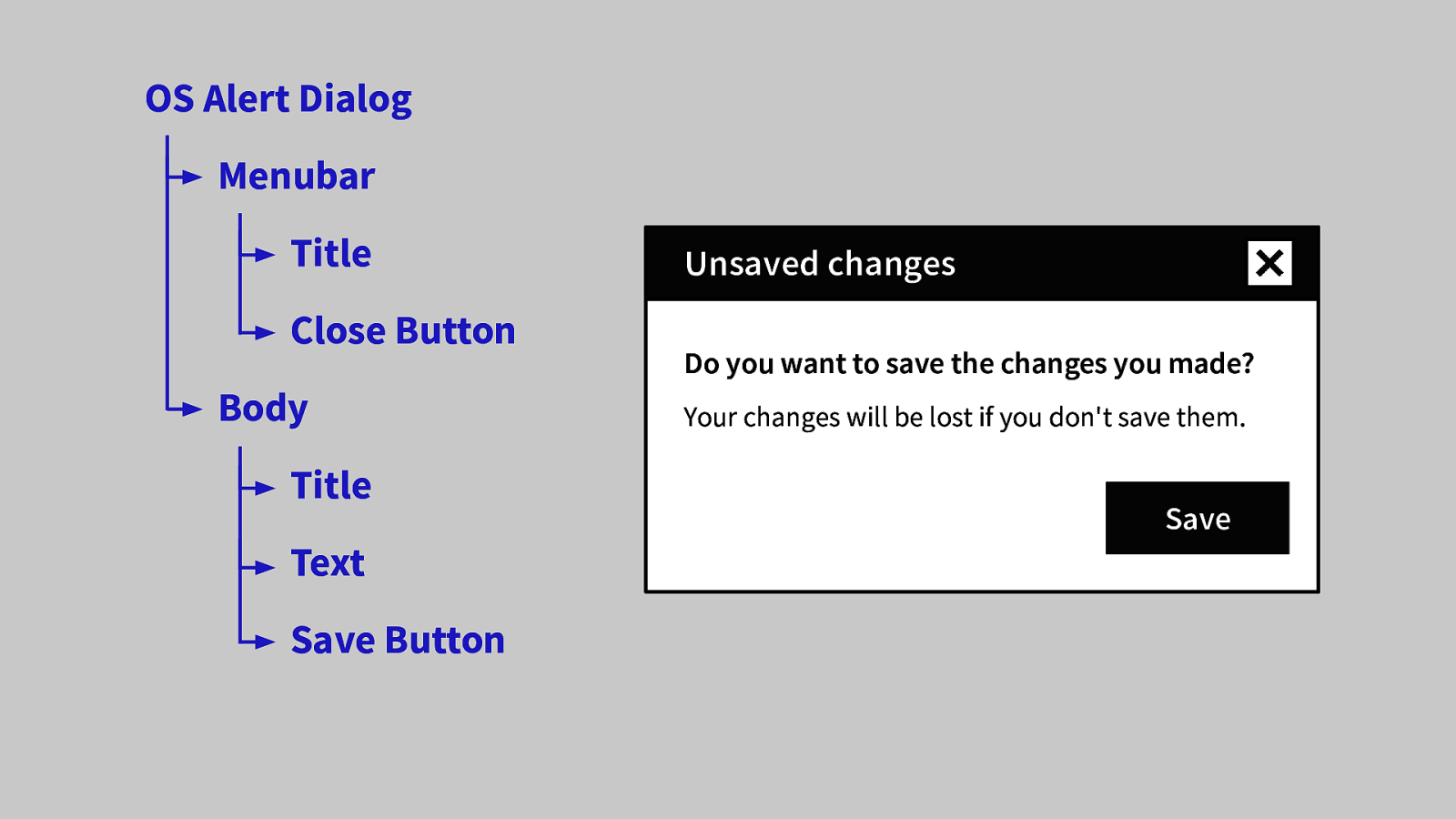

Slide 16

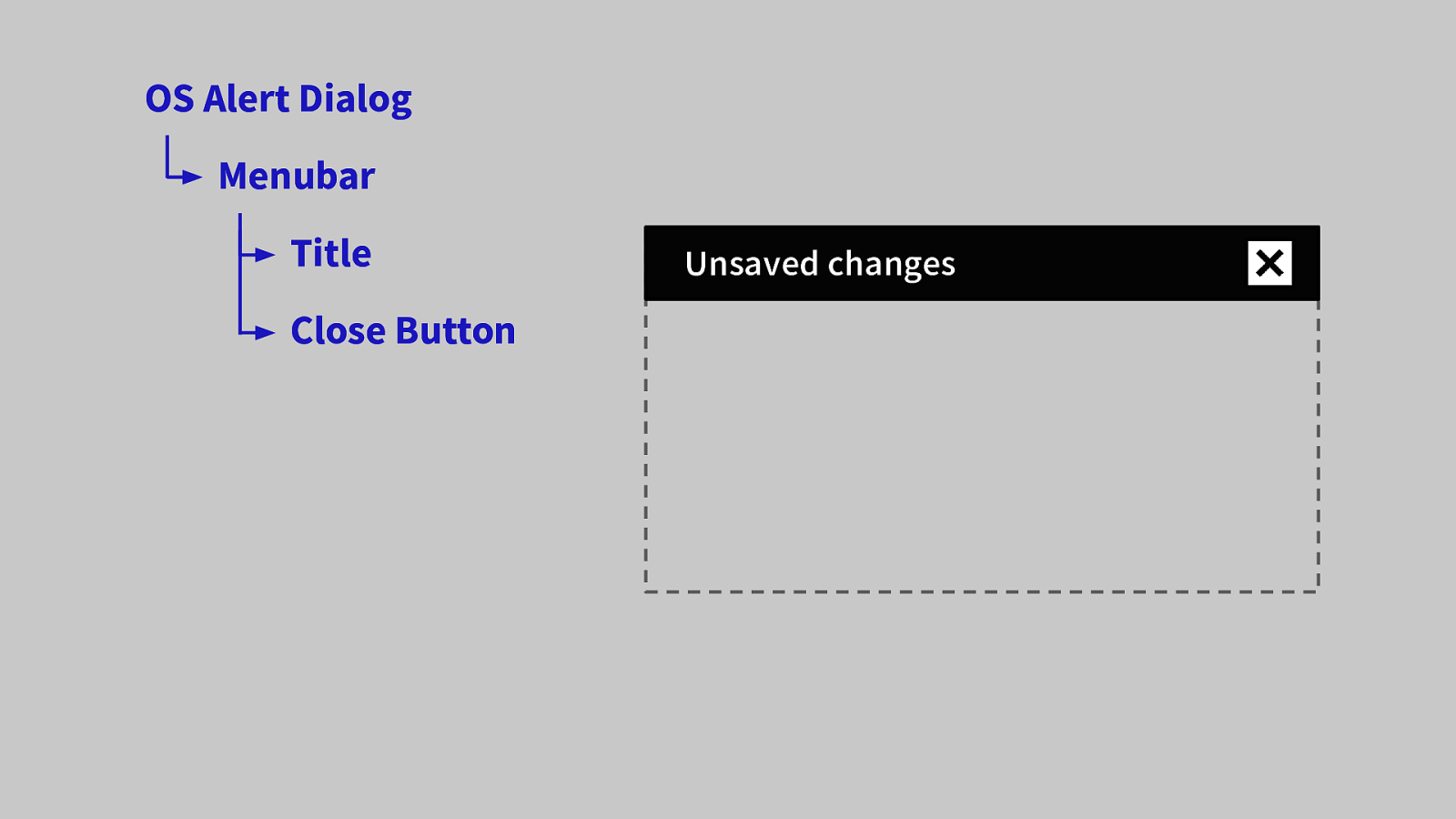

- Let’s say an operating system alert dialog, that’s a pretty commonplace thing for UI

Slide 17

- Starting from the top down, we have a menubar

- That’s the anchor that we’re going to attach everything to.

Slide 18

- And then we add a title for the menubar, so we know what it’s all about, and what contents we can expect to find

- If you’re using a screen reader, titles are really helpful,

as it saves you from having to dig around inside the component to figure out what it’s for

- If your product is a single page application, it’s also really helpful to update your title to reflect the purpose of the current view instead of just displaying the app’s name

- This is one of those circumstances where we actually don’t want a more app-like experience on the web

Slide 19

- Moving on—we might also need to close this dialog window once we learn what it’s for,

- So we include a close button in the menubar for quick access

Slide 20

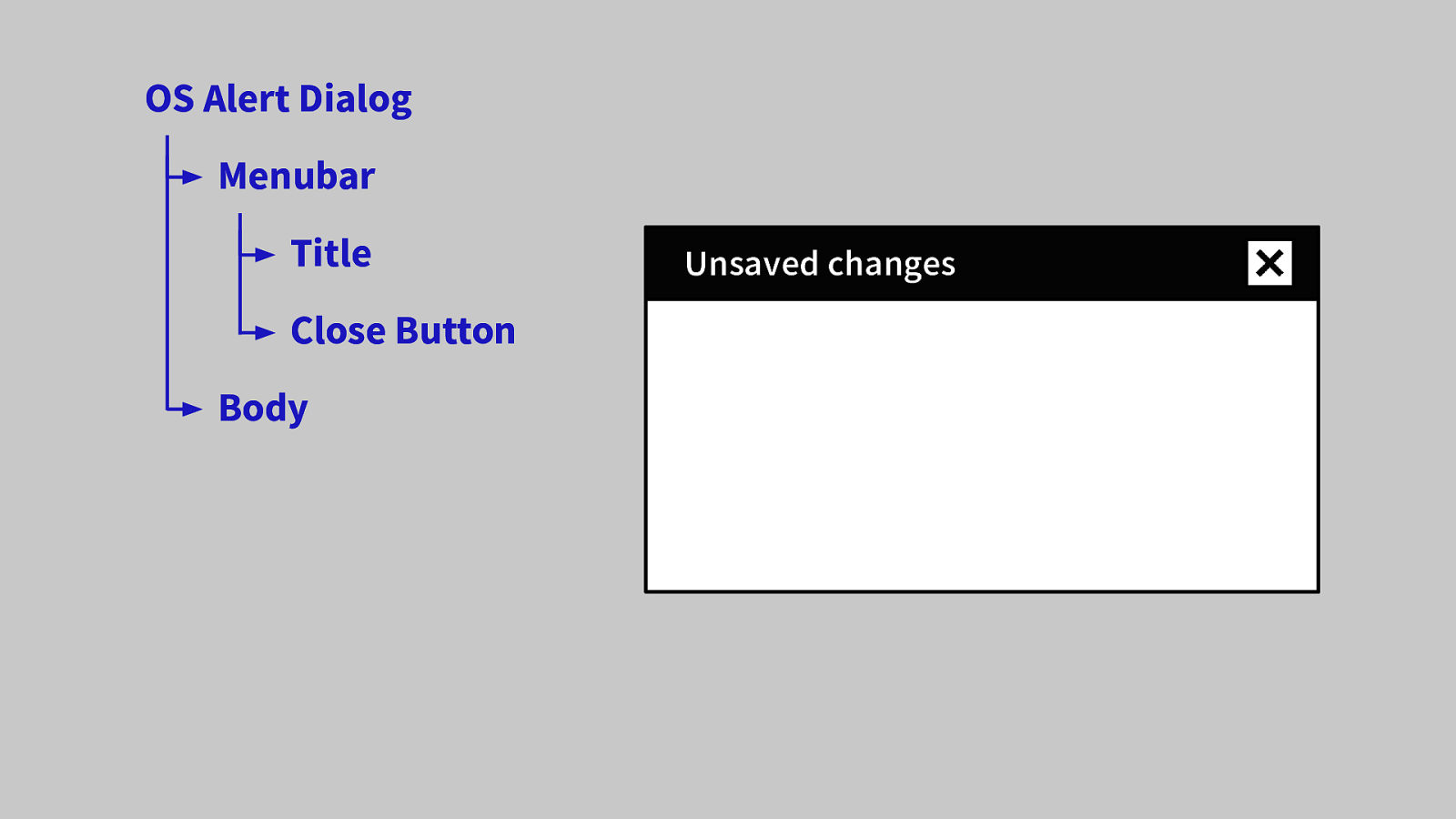

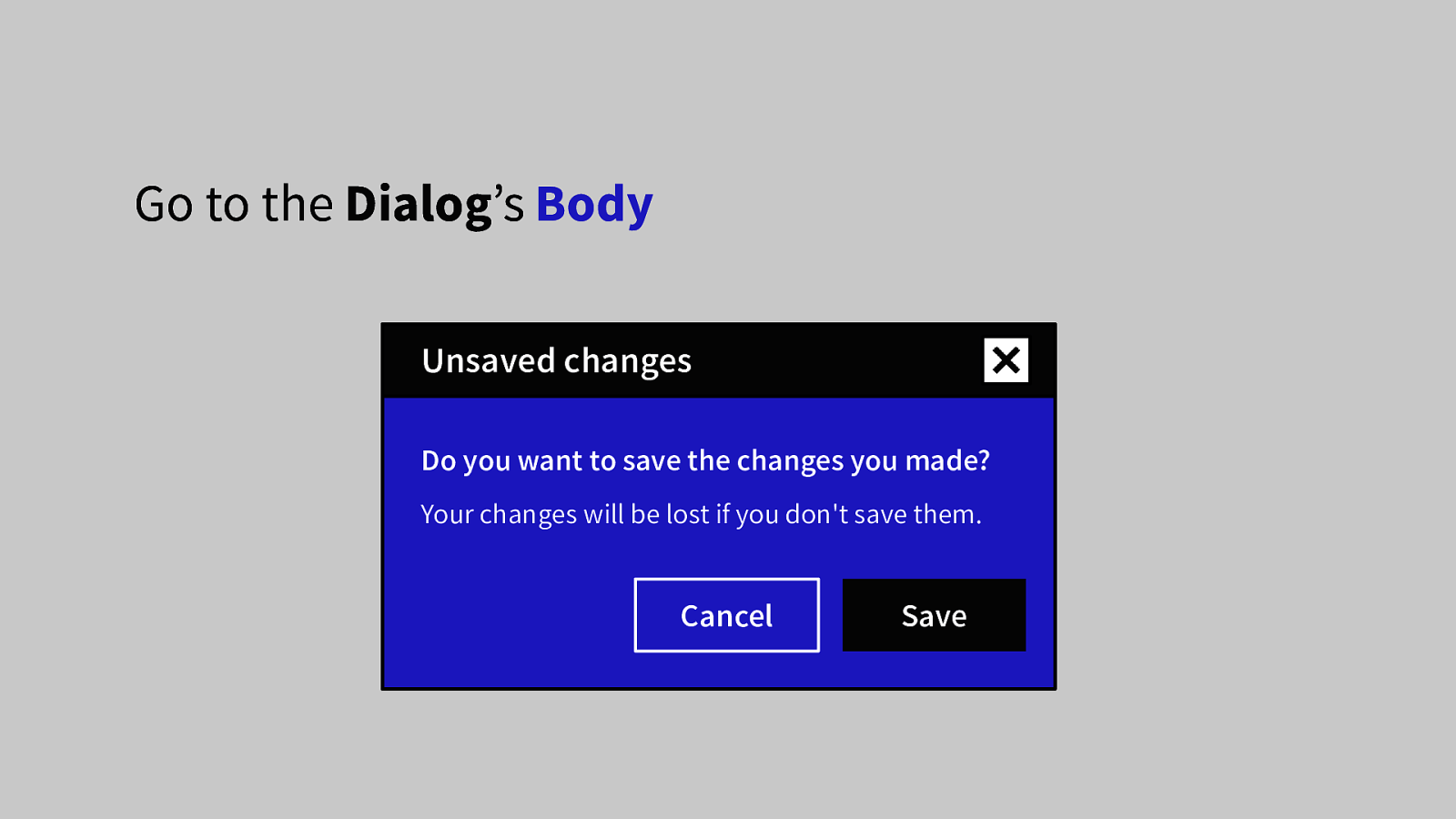

- Then we add the body of the dialog, the place where we can put the bulk of the dialog’s main content

Slide 21

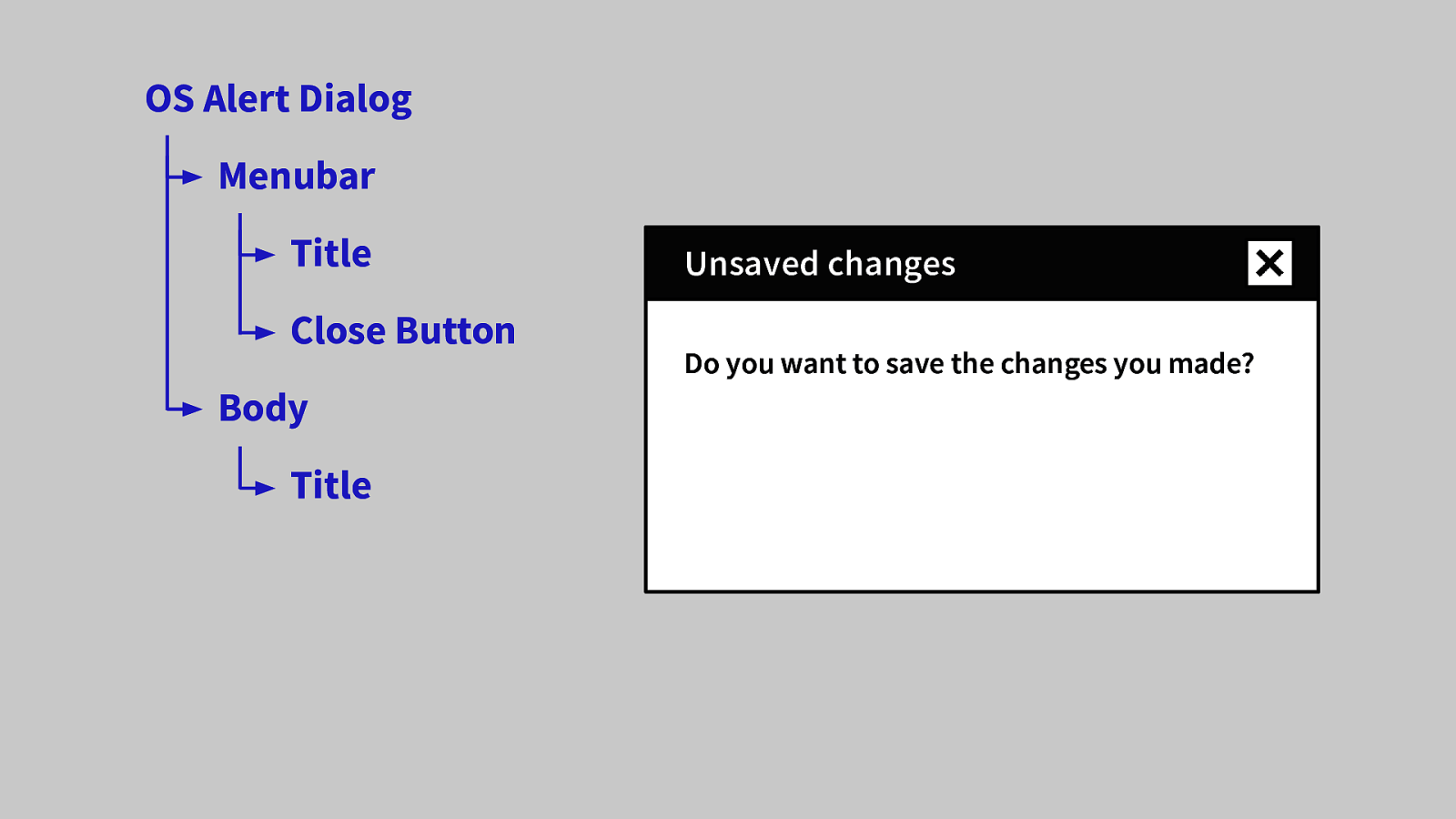

- In the dialog’s body there’s another title, which asks us if we want to save the changes we made to the thing we were working on

Slide 22

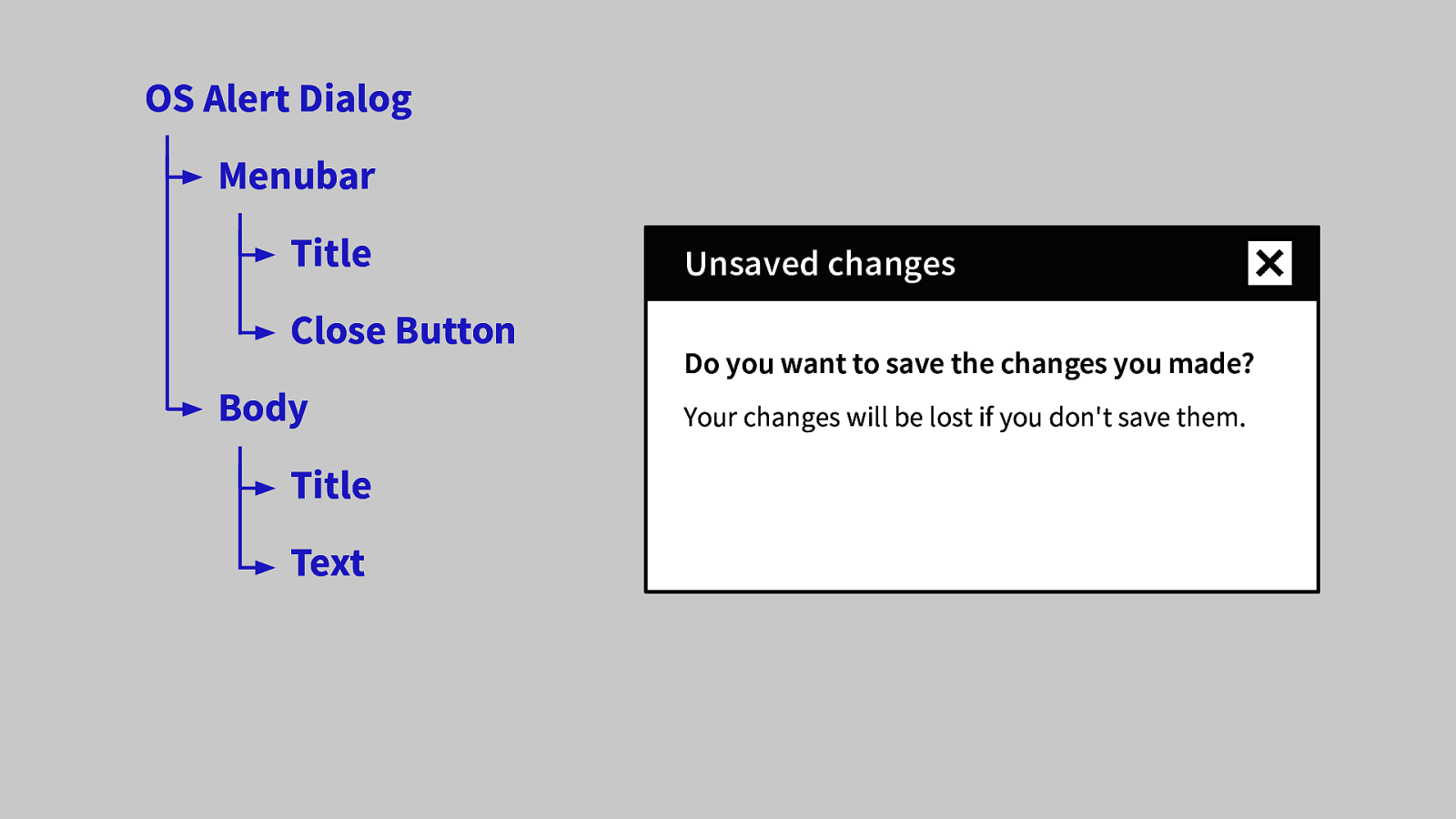

- We then add text to the body, which will provide more information about what happens if you choose not to save

Slide 23

- Then we add a save button, to allow us to commit to saving the changes we made

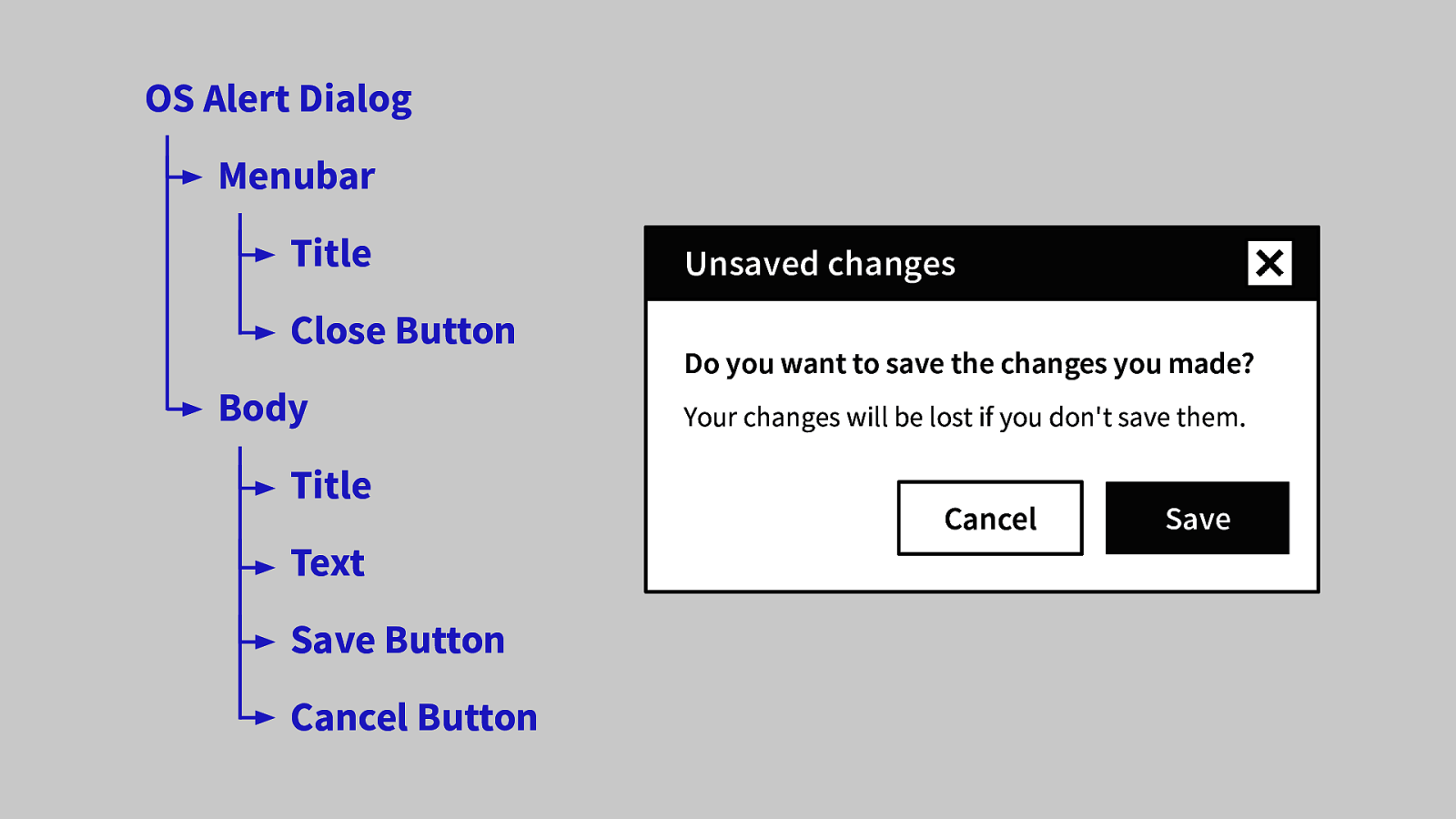

Slide 24

- And an accompanying cancel button, in case we don’t

- And presto! We have a dialog component!

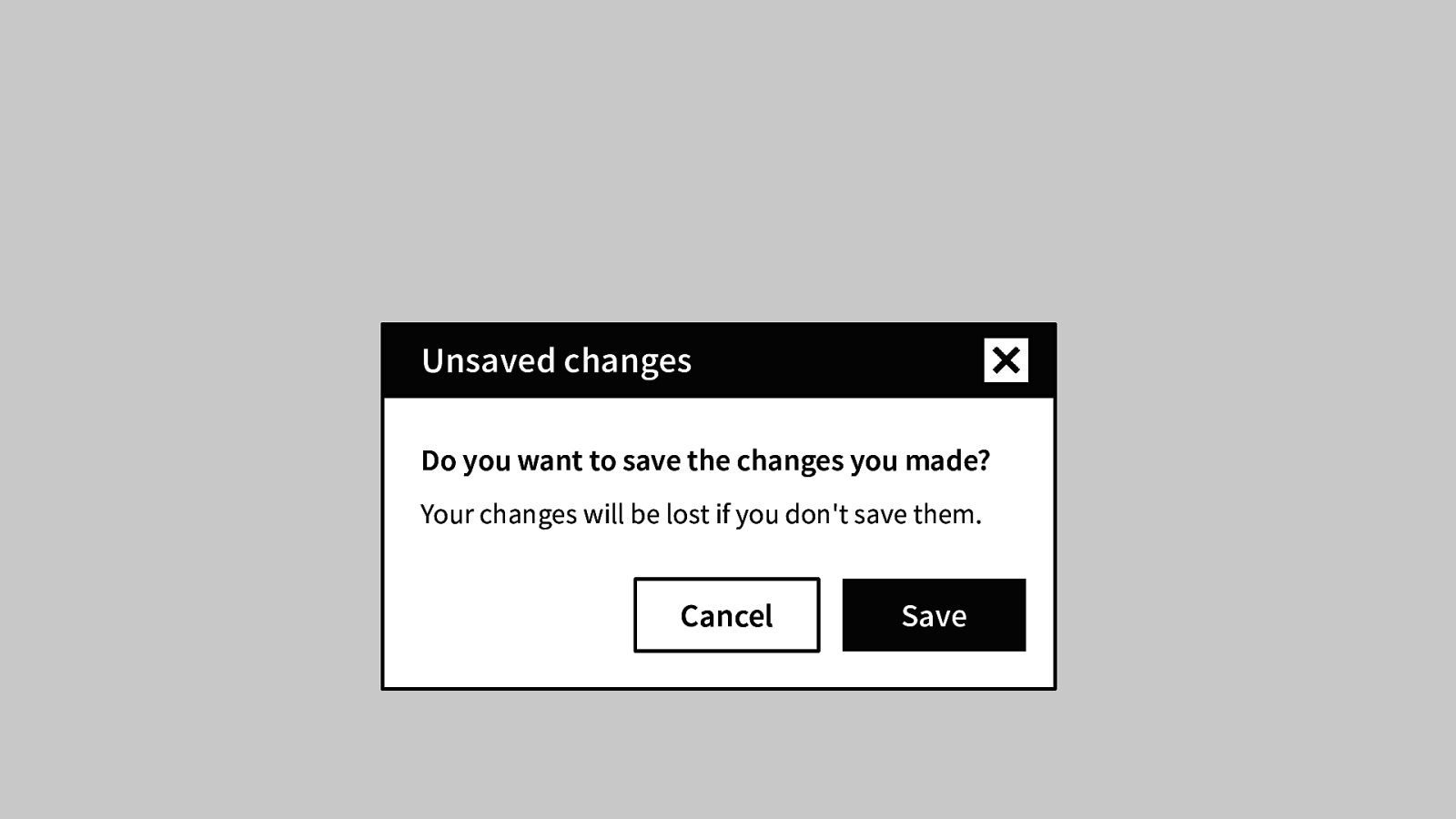

Slide 25

- We can now speak computer to computer to get what we want

- This is because these collected objects have accessible names and are therefore present in the Accessibility Tree

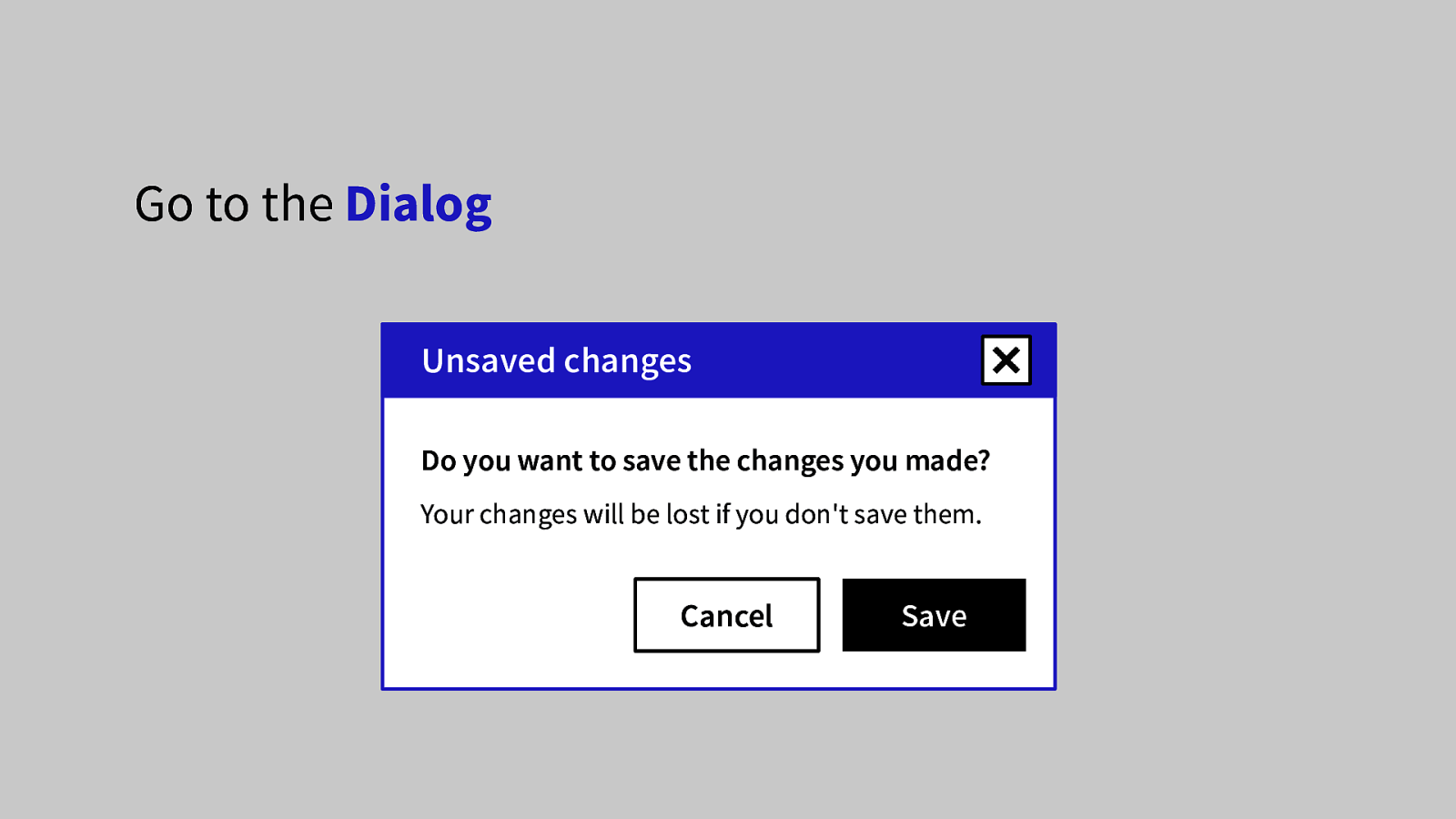

Slide 26

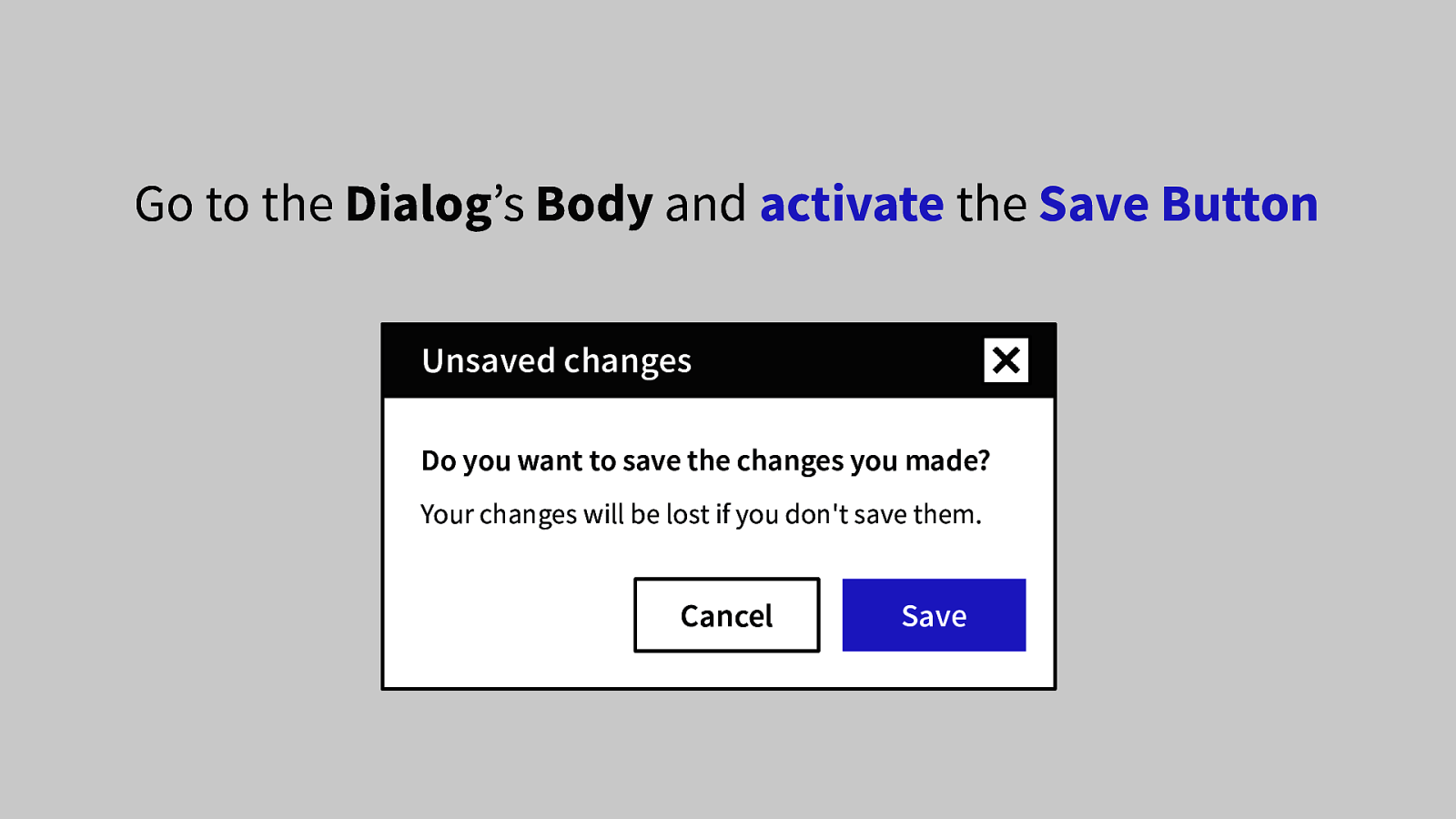

- I can programmatically say, “Go to the dialog.”

Slide 27

Slide 28

- “And activate the save button.”

- And it works! How cool is that!

- You might also be thinking this feels a lot like traditional software tests, and yup! You’re right. They’re close friends.

Slide 29

- So, this all might seem a little pedantic, but please, bear with me for a bit

Slide 30

- We do have this dialog component, but there’s more to it than just that

Slide 31

- Interface components have to have a place to live, and that place is an operating system

Slide 32

- Operating systems also include components that allow us to navigate to, and access the stuff you store on them

Slide 33

- It’s also the place we install and run programs

Slide 34

- And all the little doodads and widgets we can’t live without

Slide 35

- And the browser, which is rapidly becoming an operating system in it’s own right

Slide 36

- The browser contains the mechanisms we use to access the web

- …aaand the web is sort of the Wild West

- In that you can write more or less whatever you want and it’ll usually work,

Which is both a blessing and a curse

Slide 37

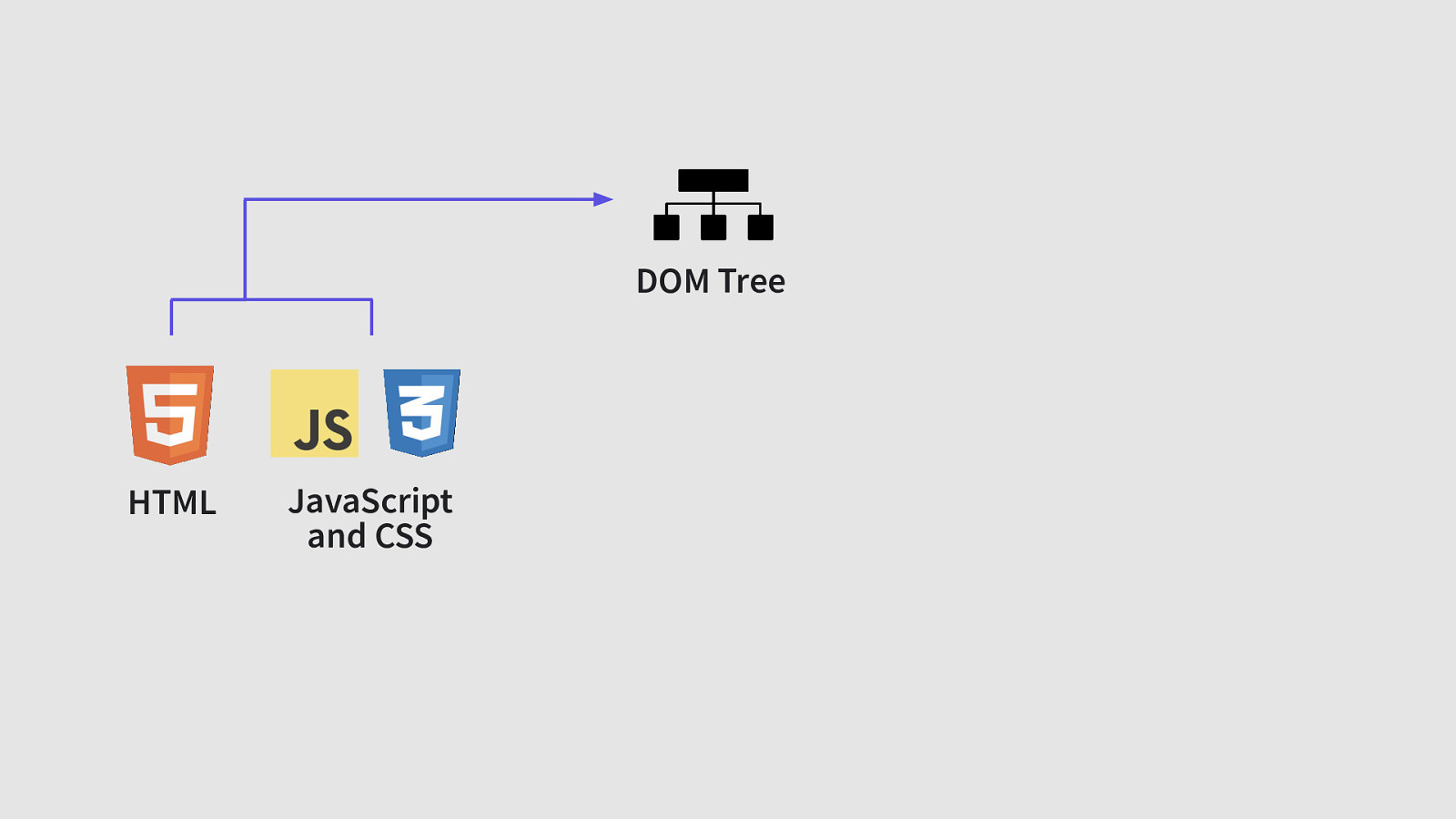

- But regardless of how you write what you write, you can’t escape the fact that you ultimately have to render HTML

Slide 38

- That HTML then has its appearance and behavior augmented by both JavaScript and CSS

- Again, there’s many ways to go about doing this,

- But they are the other two requisite parts that make up the whole that is a contemporary website or web app

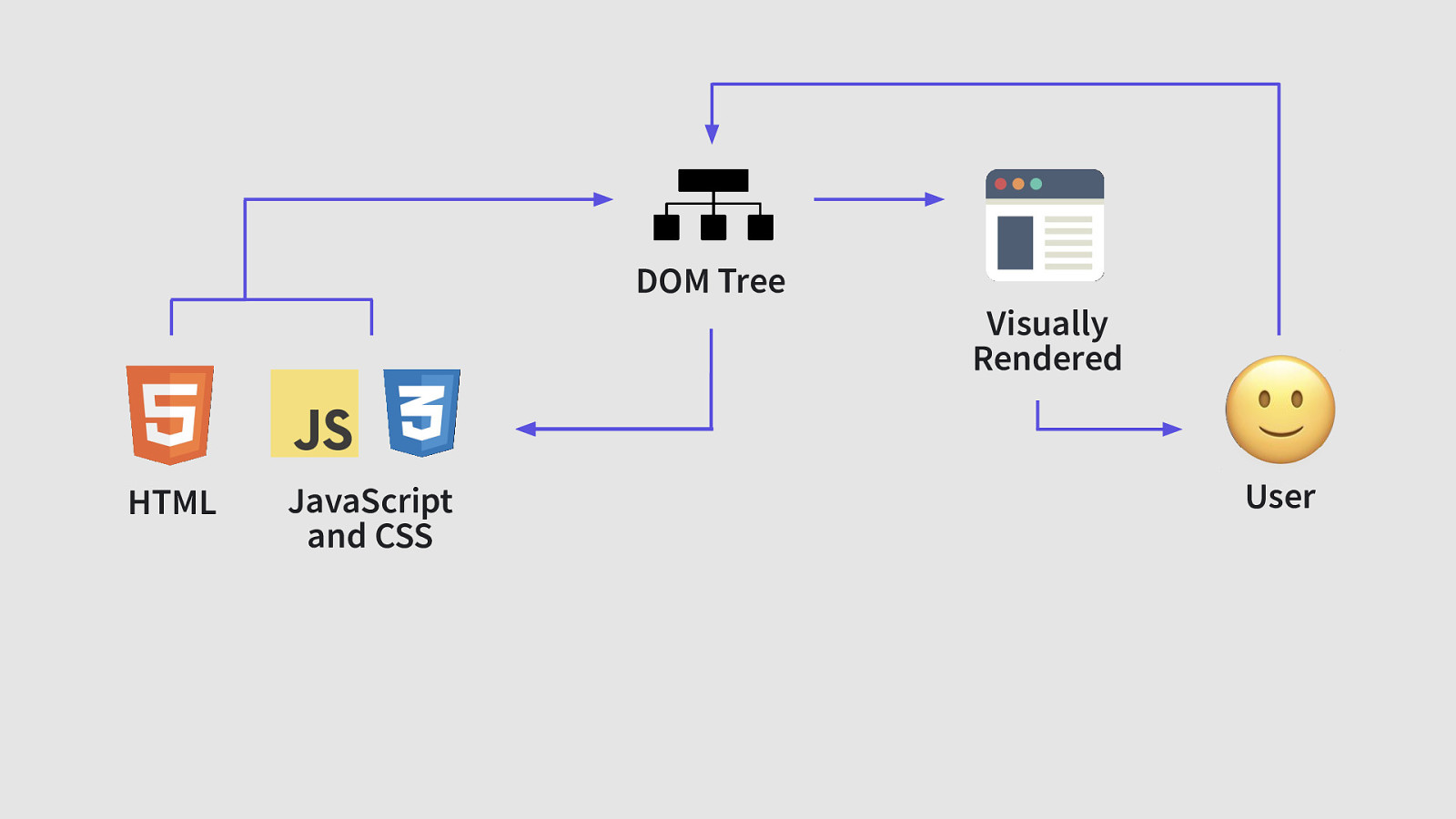

Slide 39

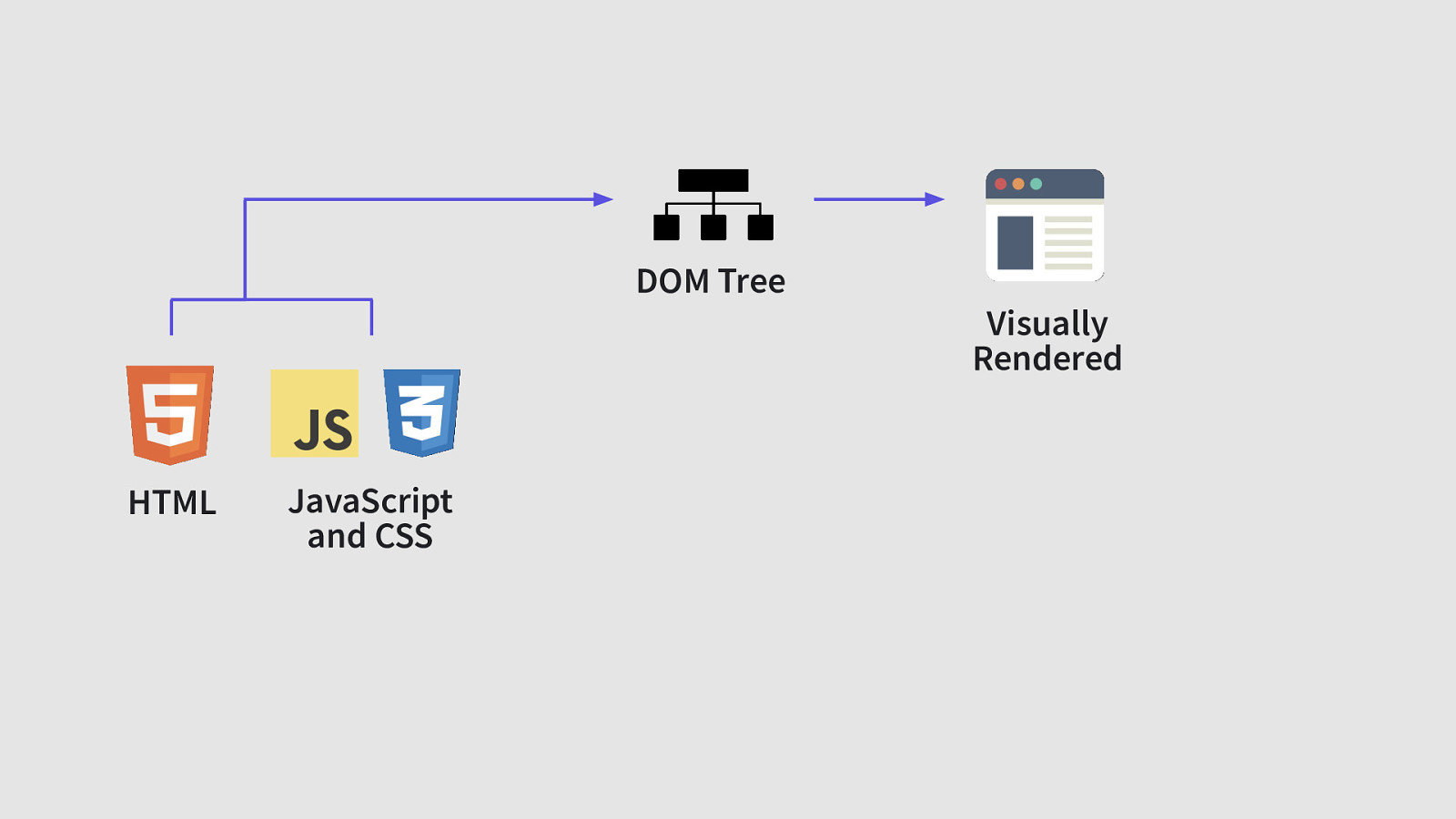

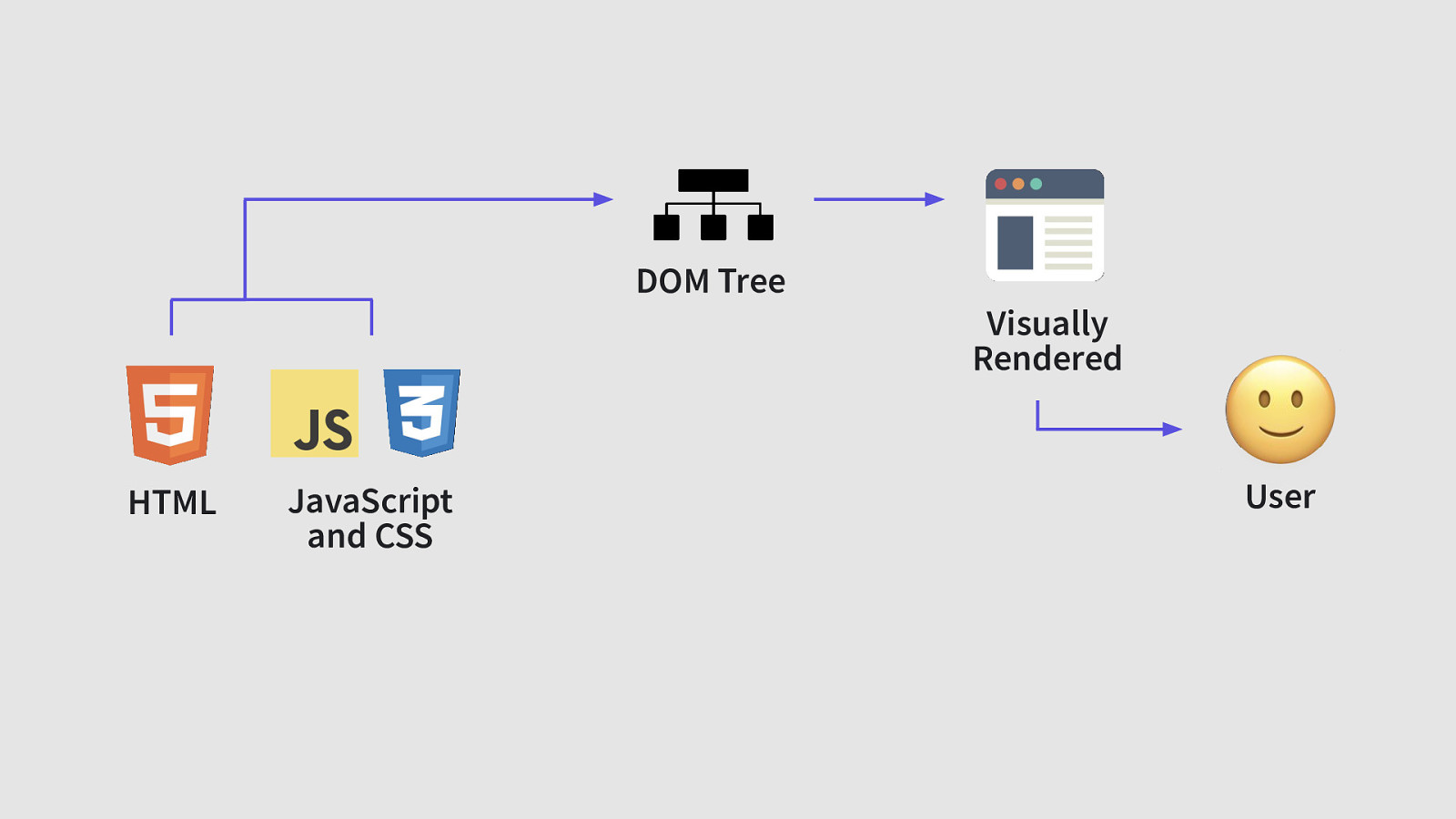

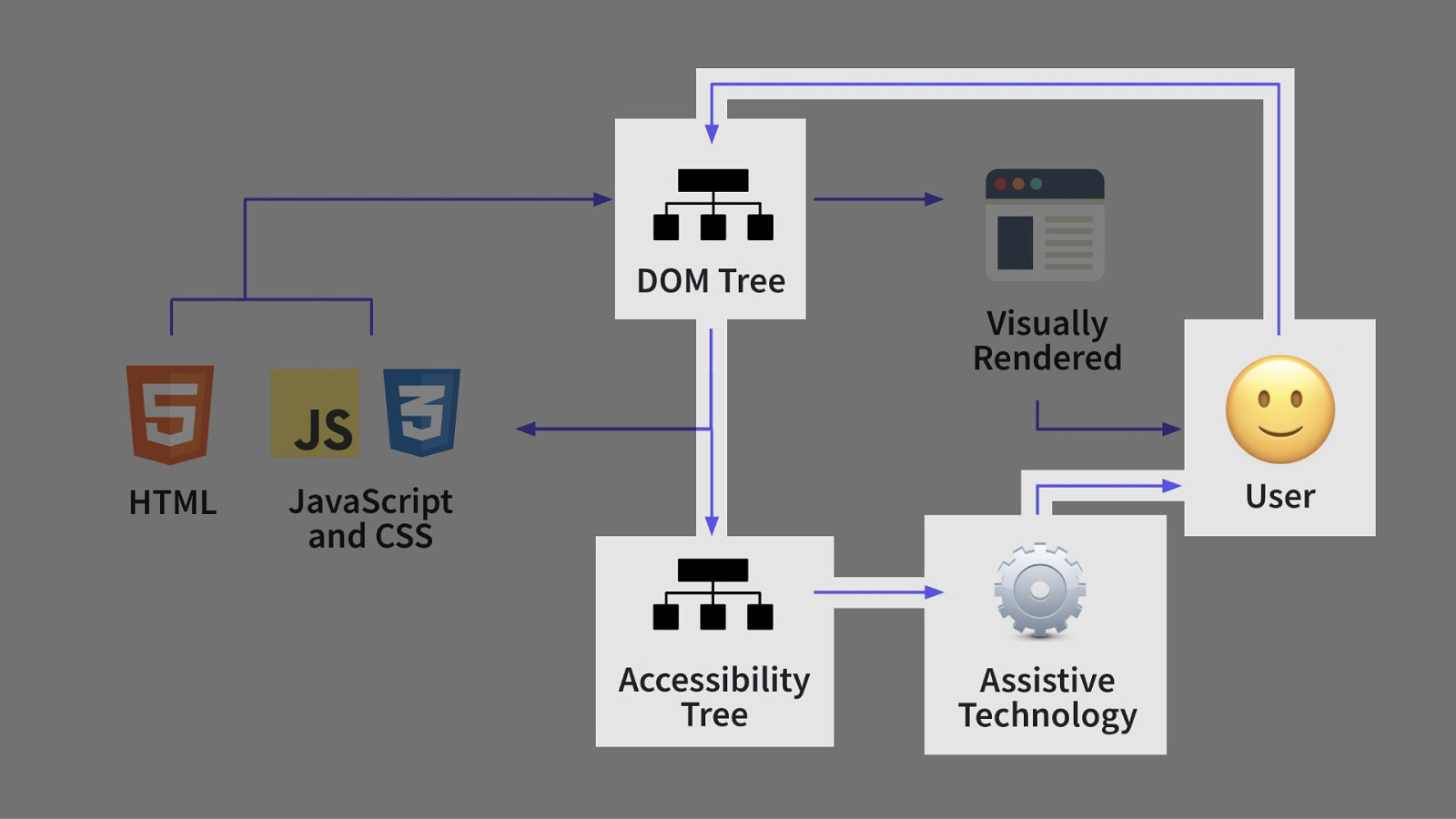

- The HTML markup, augmented by both JavaScript and CSS creates the Document Object Model, or DOM tree,

which is a programming interface for websites

- I know y’all know all of this, but please stay with me for a moment here

Slide 40

- Browsers then read the DOM, and all the information contained within it to draw an interface

Slide 41

- Which is then shown to a user

Slide 42

- The user can then take actions, which updates the DOM,

- Which in turn updates what is visually rendered, allowing us to make our websites dynamic

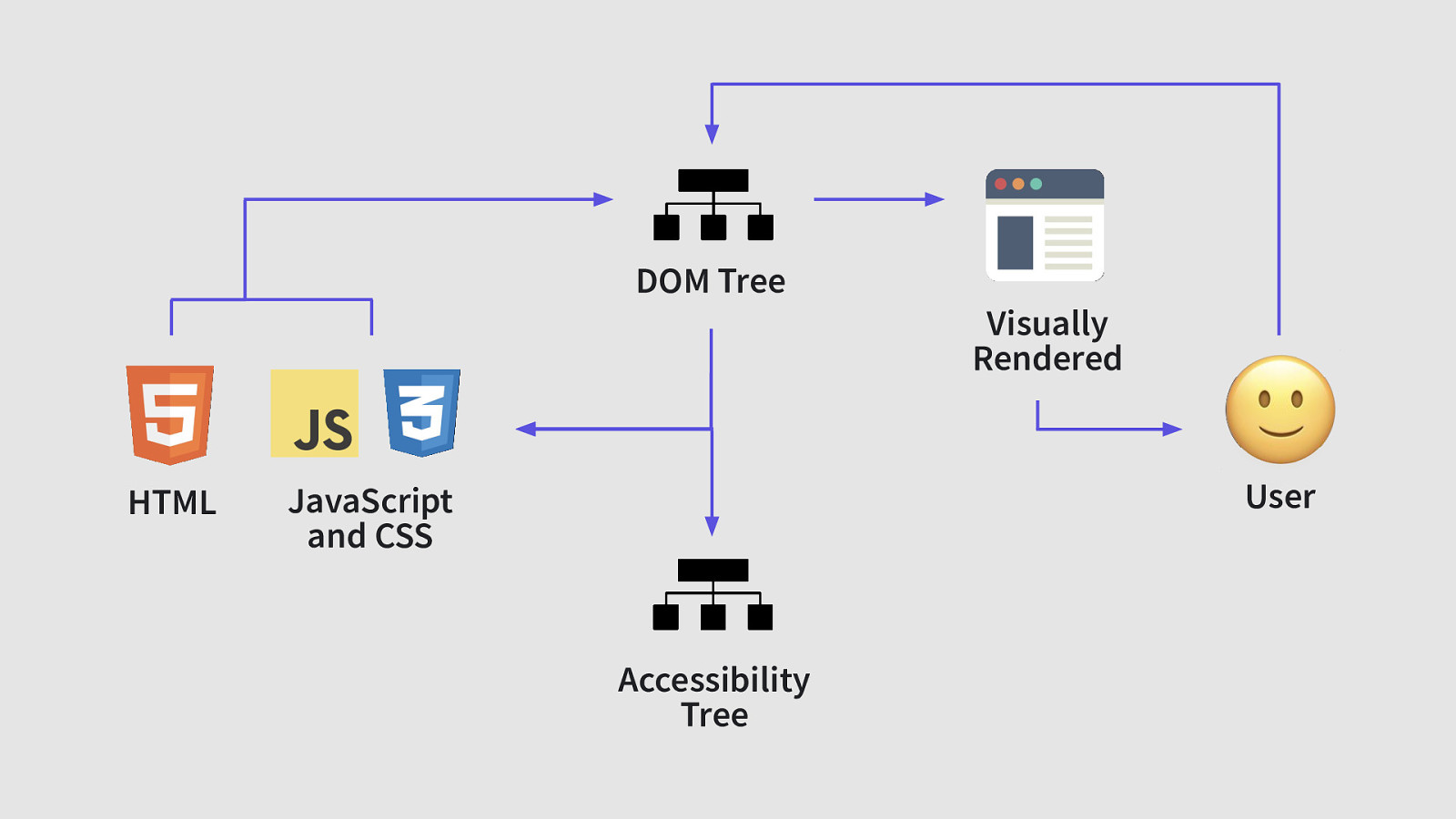

Slide 43

- Running in parallel is the Accessibility Tree, which is sampled from the generated DOM

- I say sampled because the Accessibility Tree will use specialized heuristics to only surface things it deems necessary

- Modern versions of the Accessibility Tree are generated after styles are computed,

as certain CSS properties such as display and pseudo element content will affect it

- So, when people tell you CSS is only about presentation, yeah… uh, it’s not exactly true

- Moving on

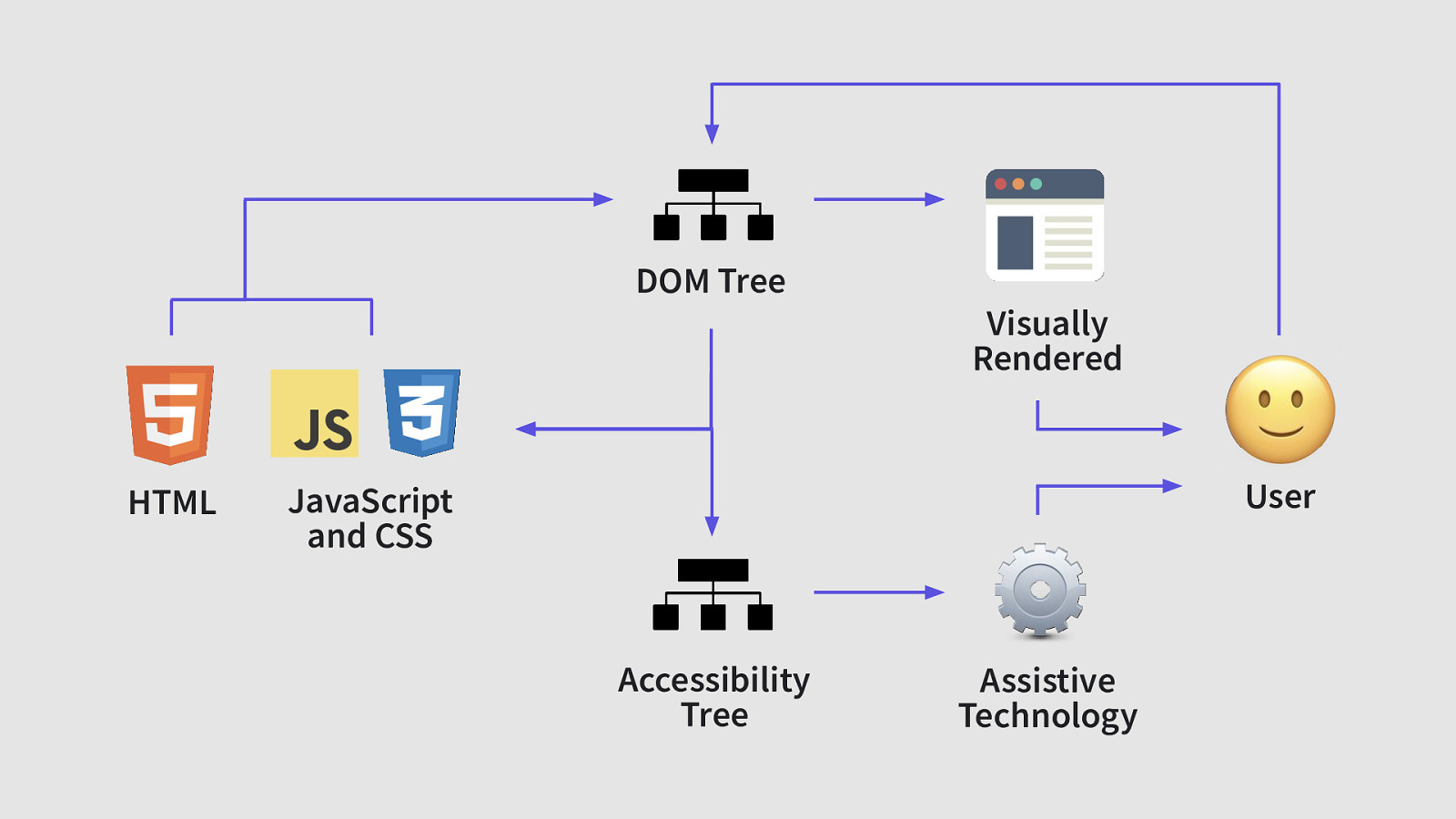

Slide 44

- This sampled version of the DOM is then read by various kinds of assistive technology, including, but not limited to screen readers

- There’s two things I’d like to point out here:

Slide 45

- First, using a visually rendered interface and assistive technology aren’t mutually exclusive things.

- It’s a fact that not all screen reader users are blind,

- And many people choose to augment their browsing with various devices that all rely on the Accessibility Tree.

Slide 46

- Secondly, the Accessibility Tree relies on the user interacting with the DOM to update,

- Accessibility Trees are effectively a “read only” technology, in that we can’t directly work with them

- There’s a few reasons for this, but the most important one is to preserve user privacy

Slide 47

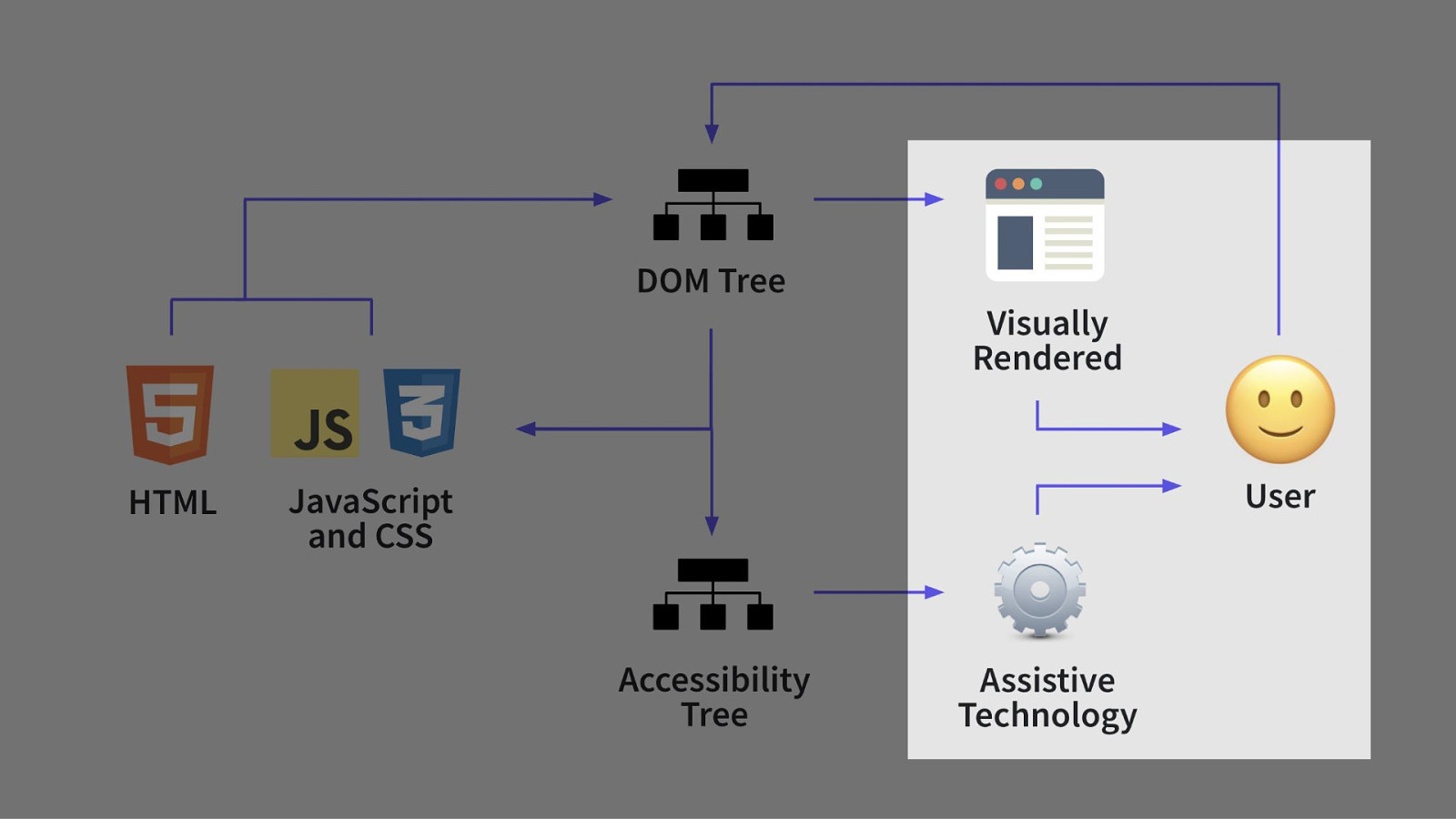

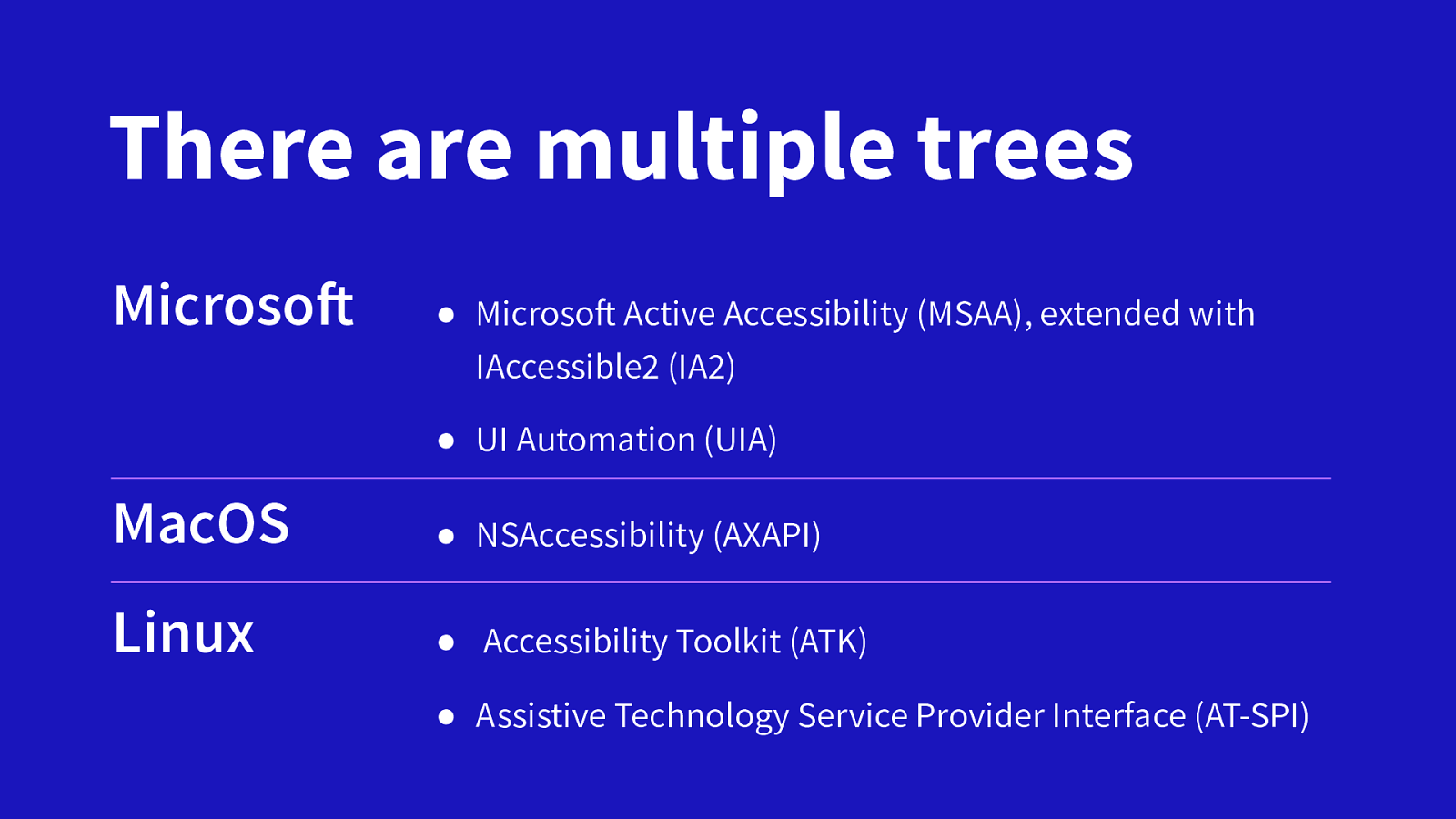

- Another thing you should be aware of is that it’s more an accessibility forest than just a single Accessibility Tree

- There are different implementations of the Accessibility Tree out there,

- Each one depends on what operating system you’re using and what version of said operating system is running

- This is due to the different ways companies have built, and updated their operating system’s underlying code throughout the years

Slide 48

Slide 49

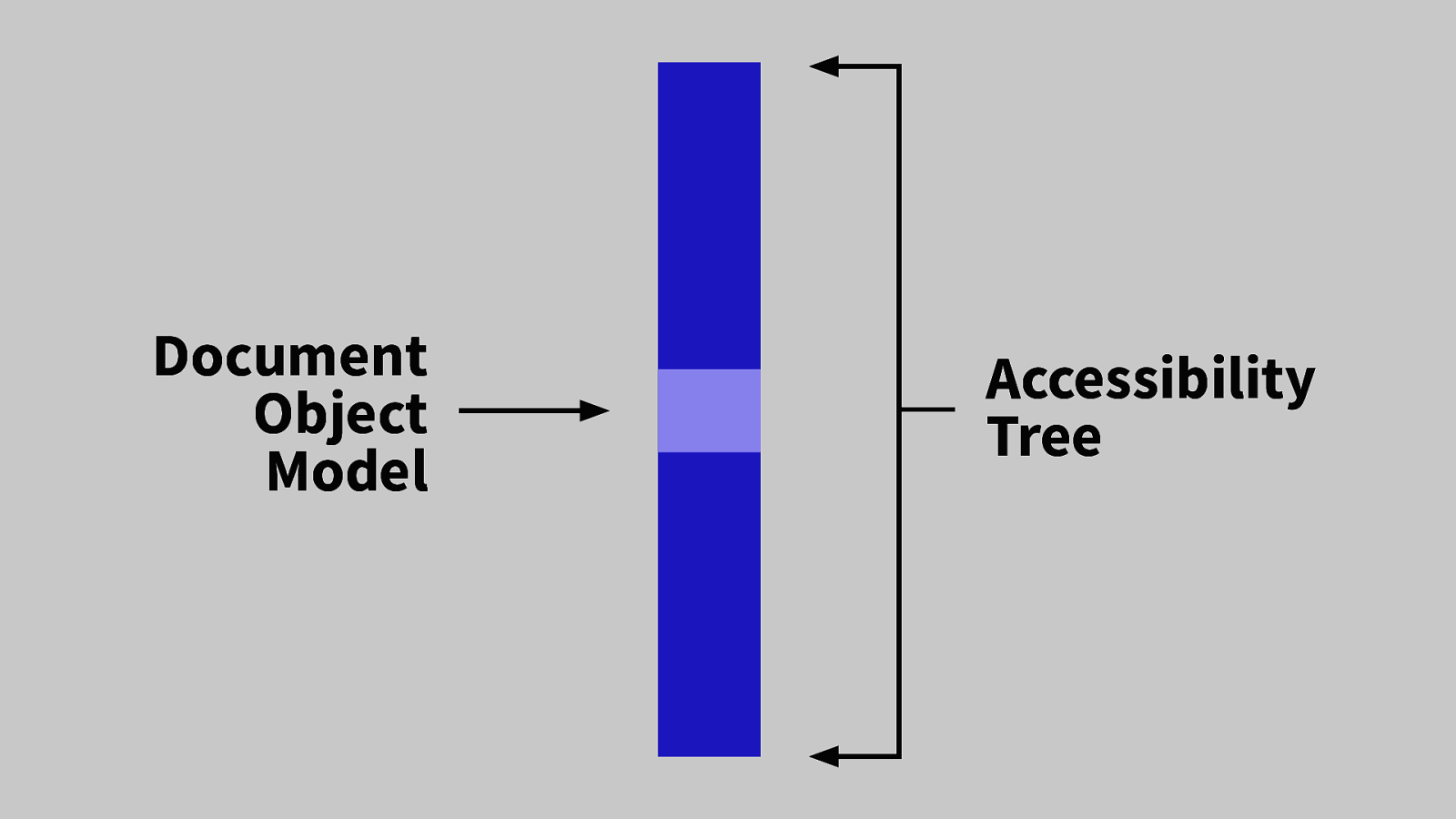

- The DOM can be a part of the Accessibility Tree,

- But the Accessibility Tree is larger, and not limited to just the contents of your browser

Slide 50

- Because of this, the accessibility tree is more brittle

- It has more to pay attention to, and it’s core technical architecture was developed before this whole “internet” thing really took off

- Meaning it didn’t anticipate the sheer amount of information we’d be throwing at it

Slide 51

- Crashing the accessibility tree, and therefore breaking assistive tech support is bad, yes

- But a large amount of information present in the DOM means that there’s an accompanying large amount of work the Accessibility Tree needs to do to figure out what’s what and report on it

- Which.

- Slows.

- It.

- Down.

Slide 52

- This can create a lack of synchronization between the current state of the page and what is being reported by assistive technology

- Meaning that a user may not be working with an accurate model of the current screen,

- And be taking action on interactive components that are no longer present, or are in a different state than they expect

- This can create the confusing experience of users activating the wrong control, navigating to a place they didn’t intend to, or unintentional data submission

- Remember, some users literally cannot the screen and therefore have no indication that this desync is present.

- So, how do we help prevent this?

Slide 53

- Start with writing semantic HTML.

- Using things like the button element for buttons instead of ARIA slapped on a div helps lessen the amount of guesswork

the Accessibility Tree has to do when it runs its heuristics to slot meaningful content into its description of the current state of the world.

- This serves to both speed up its calculation and makes what it reports more reliable

Slide 54

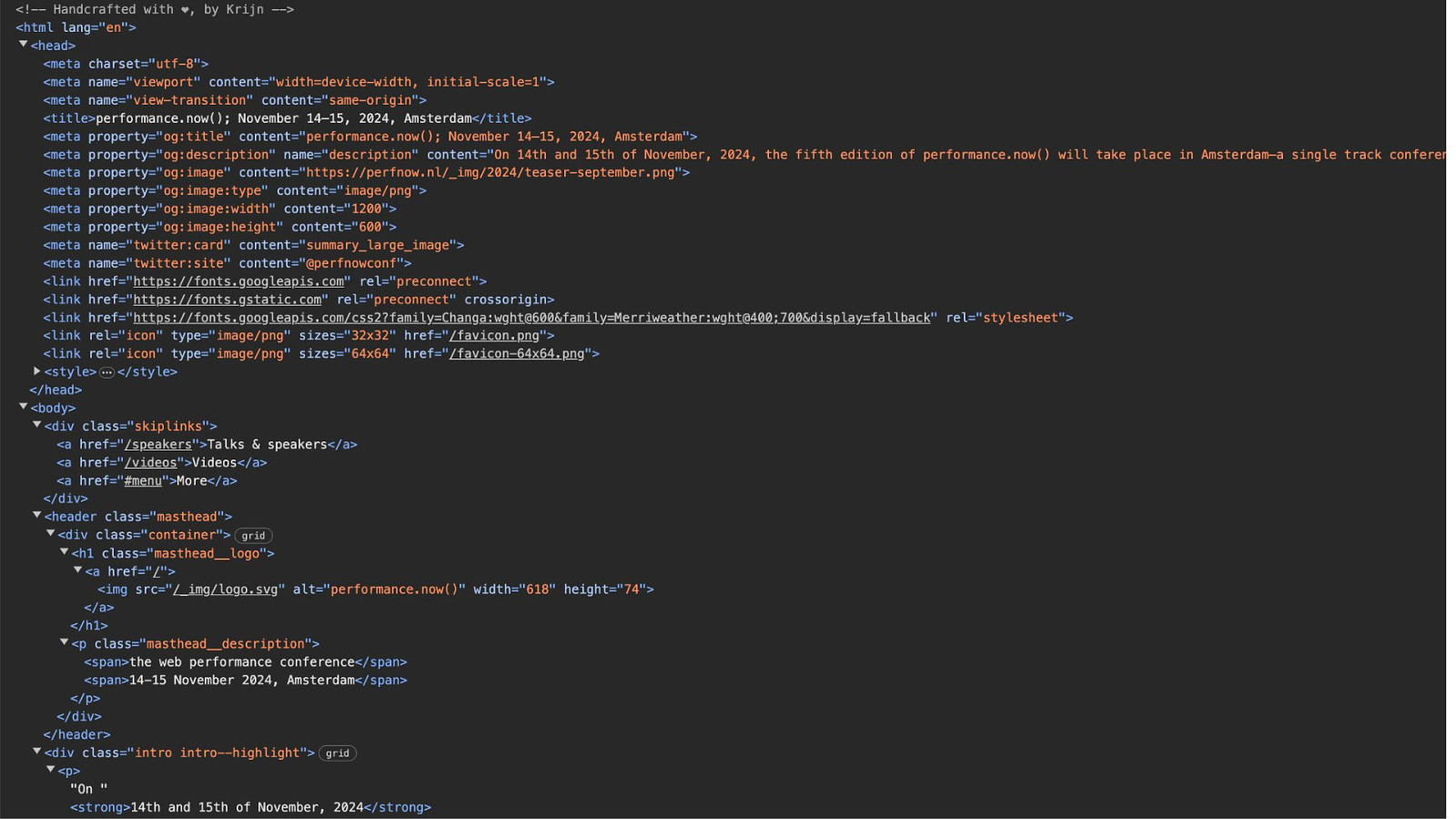

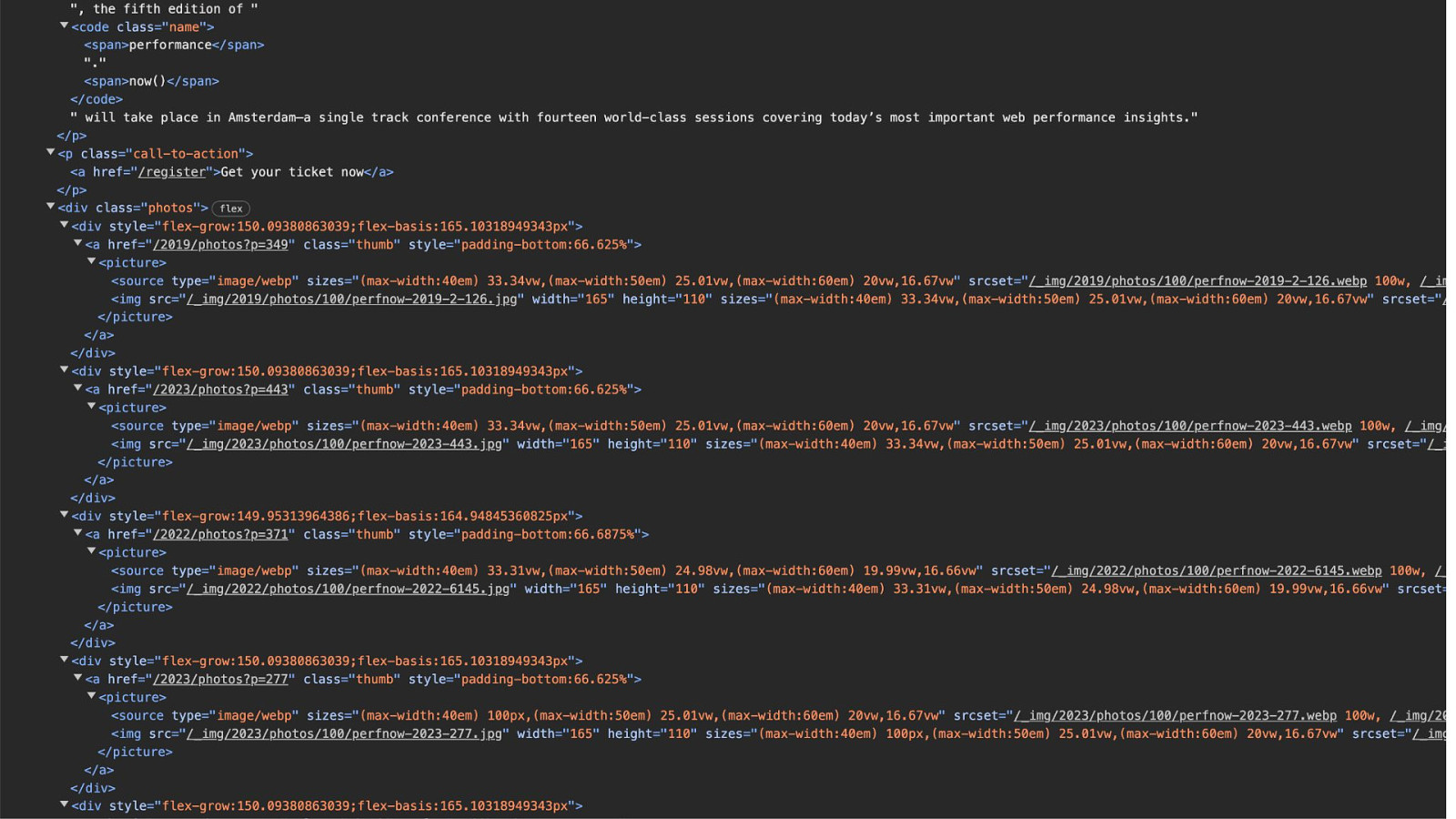

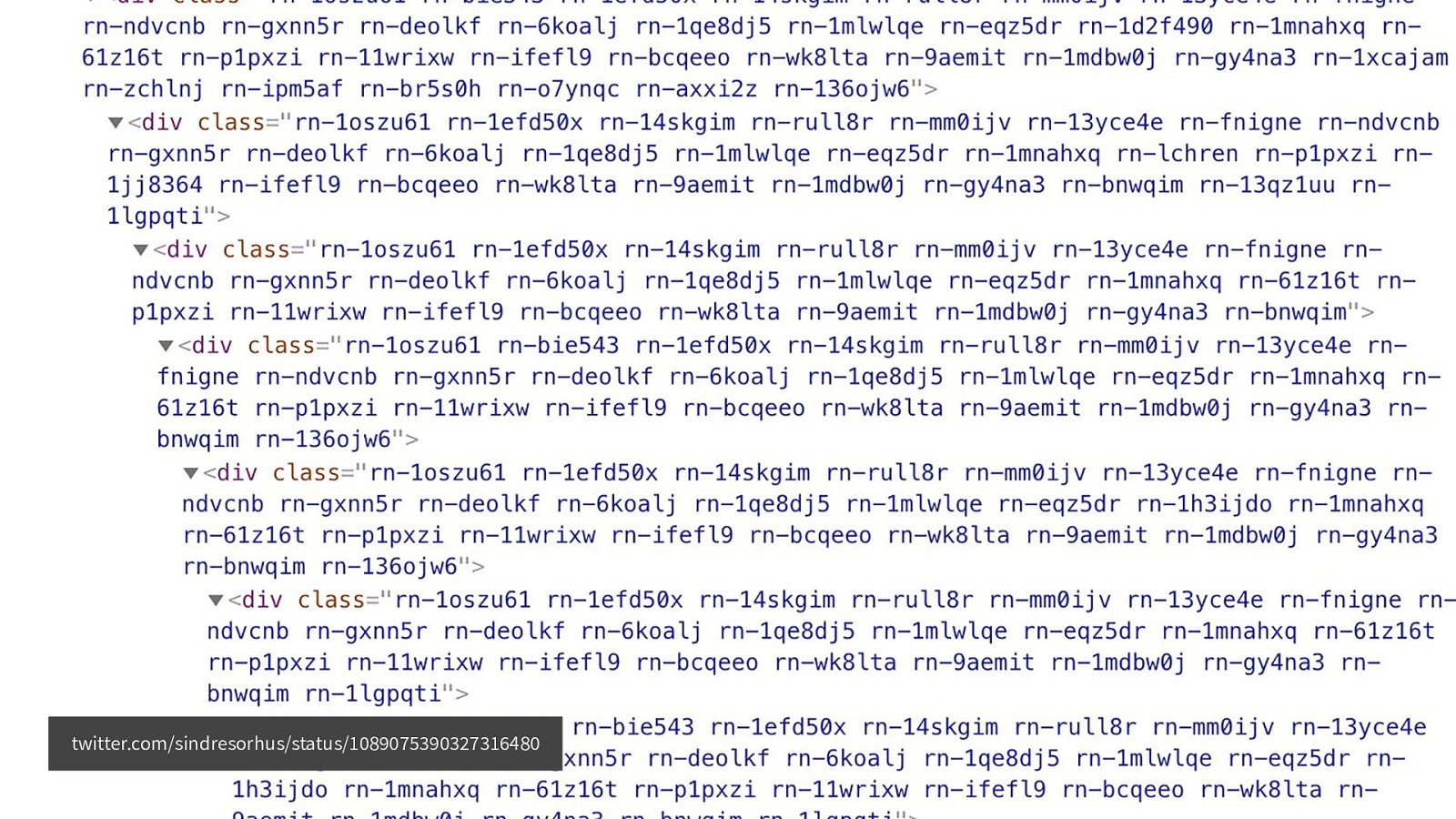

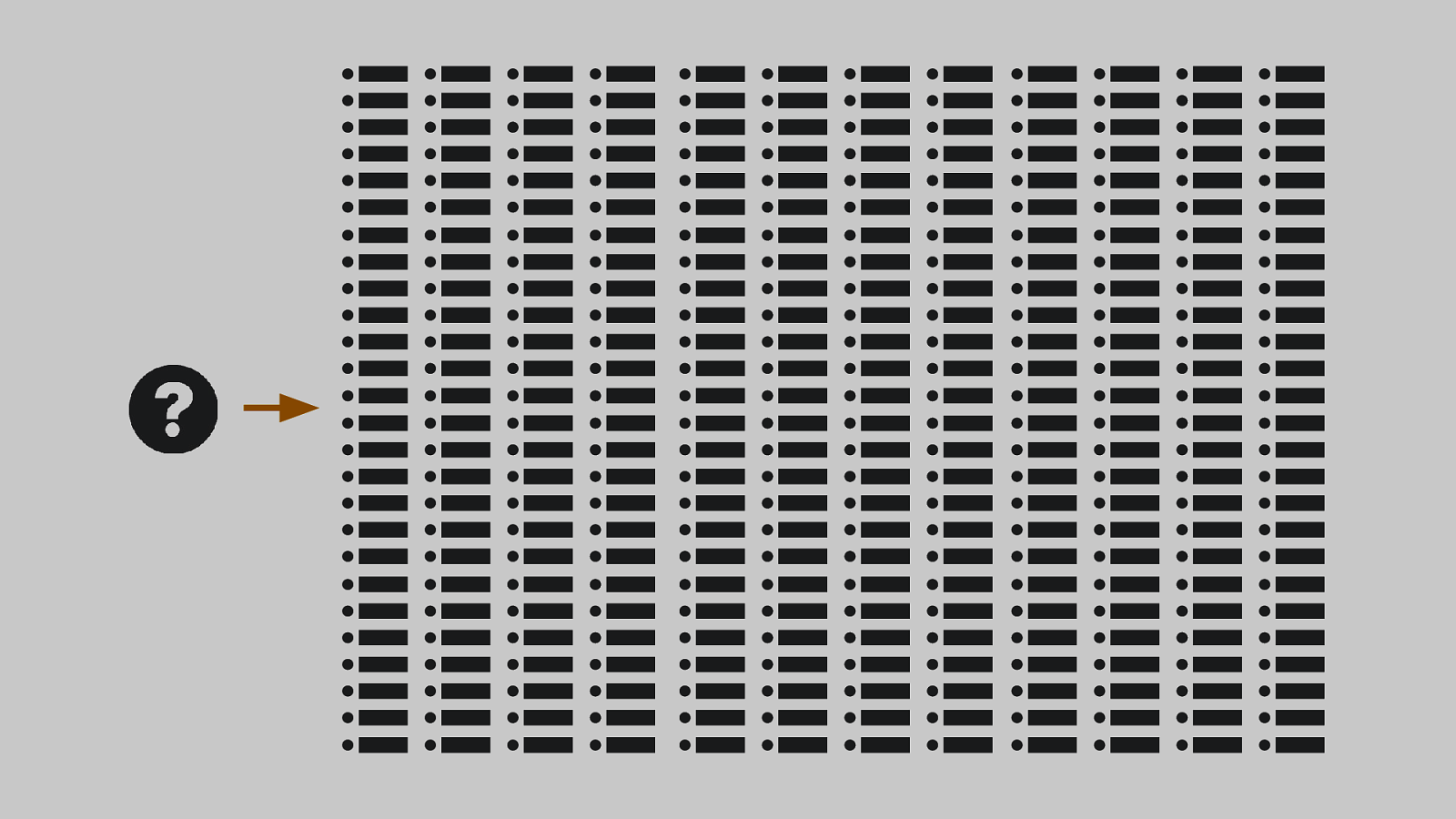

- And speaking of semantic HTML

- Here’s the raw, living DOM of an actual website

- In fact, it’s the homepage for this conference!

Slide 55

- Even a static, performant website contains a lot of information a computer has to chew through

Slide 56

- Again, utilizing semantic HTML helps reduce the effort it takes to generate the Accessibility Tree from the DOM’s contents

Slide 57

- And unfortunately, using semantic HTML is kind of a rare thing these days, which is partly why I’m here giving this talk

- But also fortunately, this site’s semantics are really good!

Slide 58

- So, big shoutout to Hidde and Krine for keeping it real

- How about a quick round of applause, folks?

Slide 59

- Okay, I think you get the gist of it

Slide 60

- Of the code I just showed you, five slide’s worth,

Slide 61

- We’ve only covered roughly half of just one page

- It’s worth pointing out that this is a relatively short and simple page and that again, it is still a lot of information to process

Slide 62

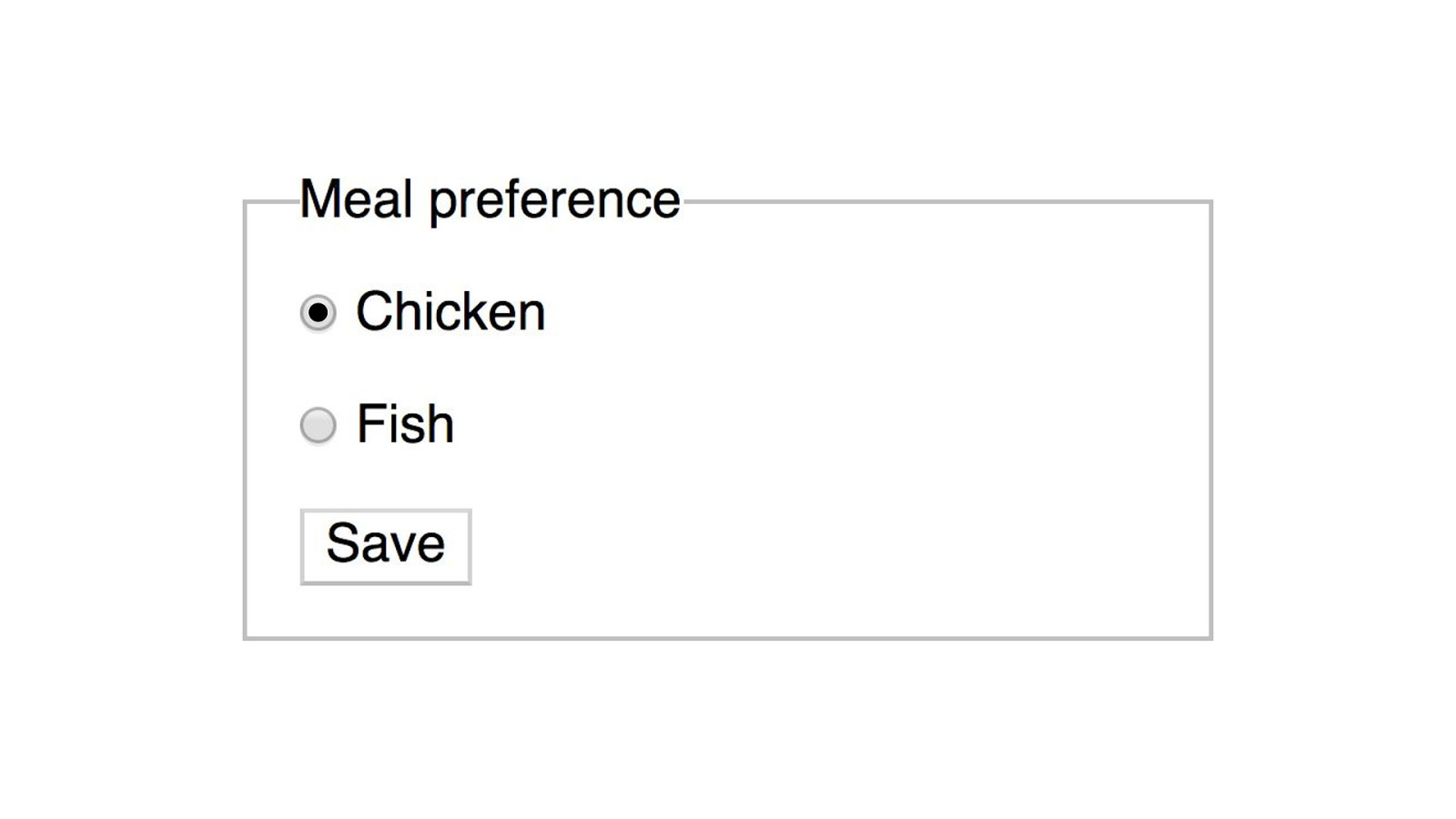

- Keeping that DOM example in mind, we now have a simple form

- It’s a pair of unstyled radio buttons asking you if you want the chicken or the fish as your meal preference

Slide 63

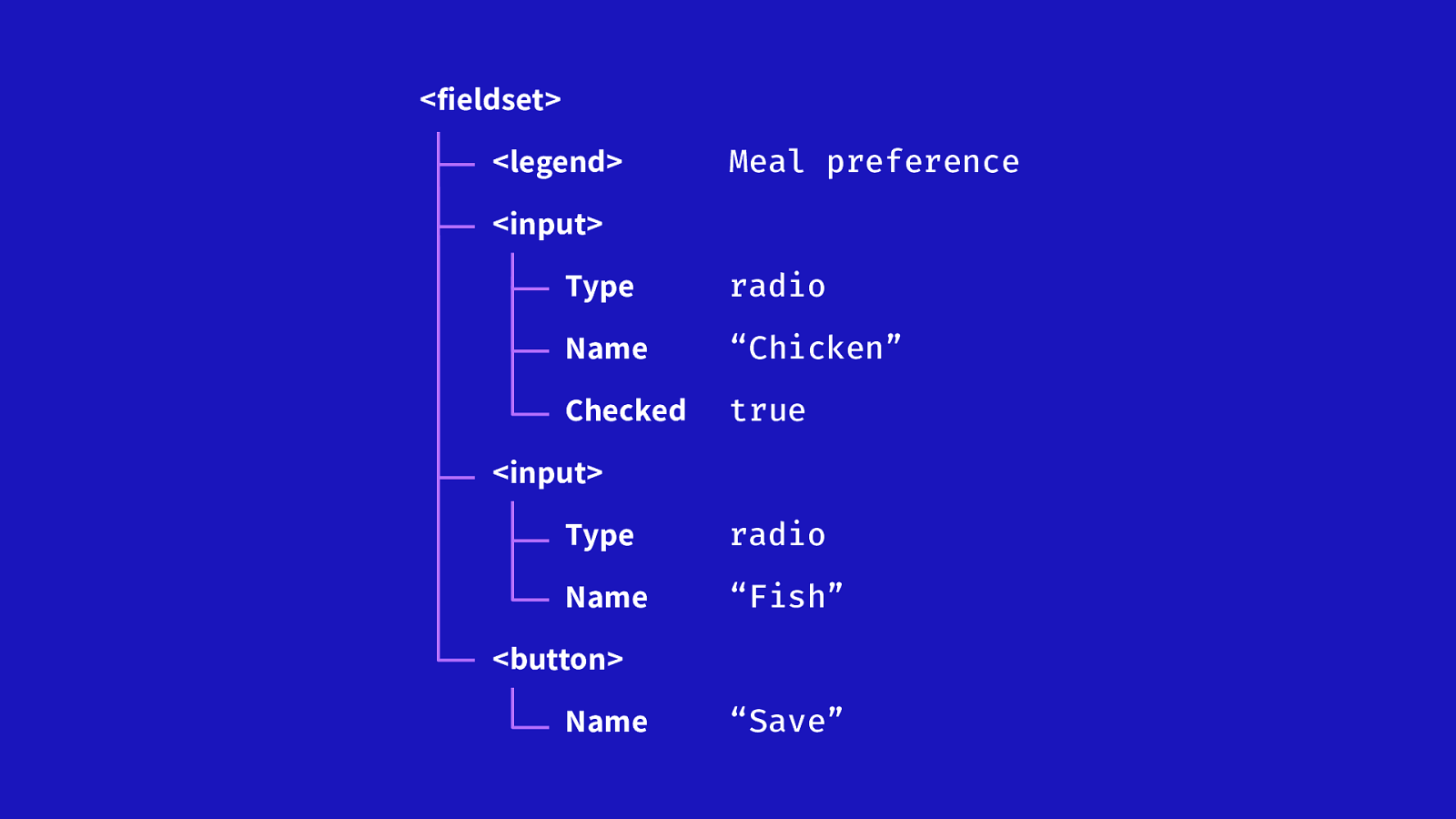

- Here’s how that form might be translated into the Accessibility Tree

- If we use semantic HTML, the names, roles, and properties are automatically filled in for us without any additional effort

- When I was speaking about how semantic HTML slots in, this is a more granular example of what I’m getting at

Slide 64

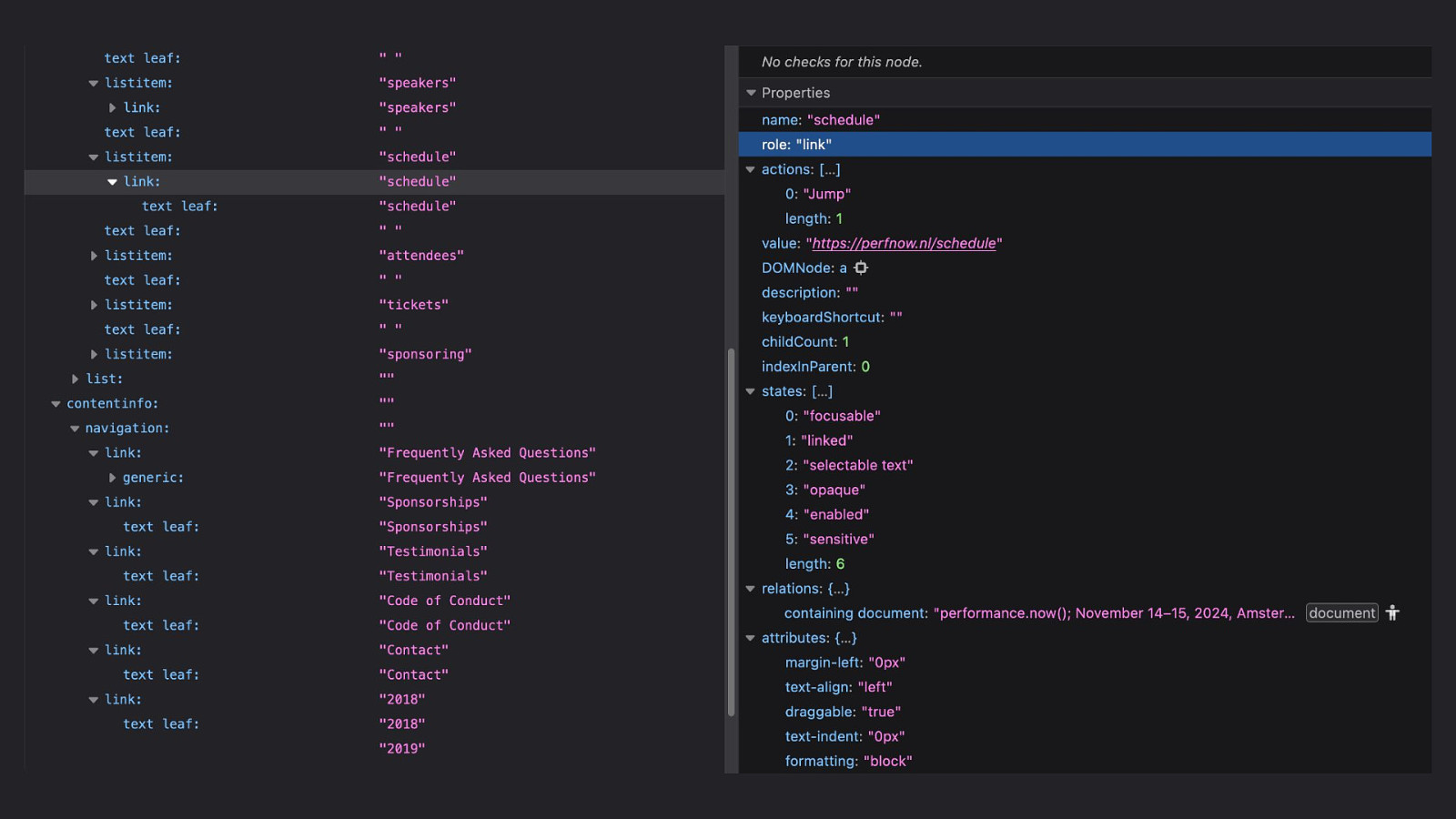

- Here’s an even more granular example, sampled again from the conference Homepage

- It’s the link for the schedule, located in the website’s primary navigation

- I’m using Firefox’s Accessibility Inspector to dig into this link’s text node

- And there’s a ton more information exposed, including attributes, states, actions, a child element count, relations, and available actions

- All of this data is used by the Accessibility Tree to help it describe the shape of things

Slide 65

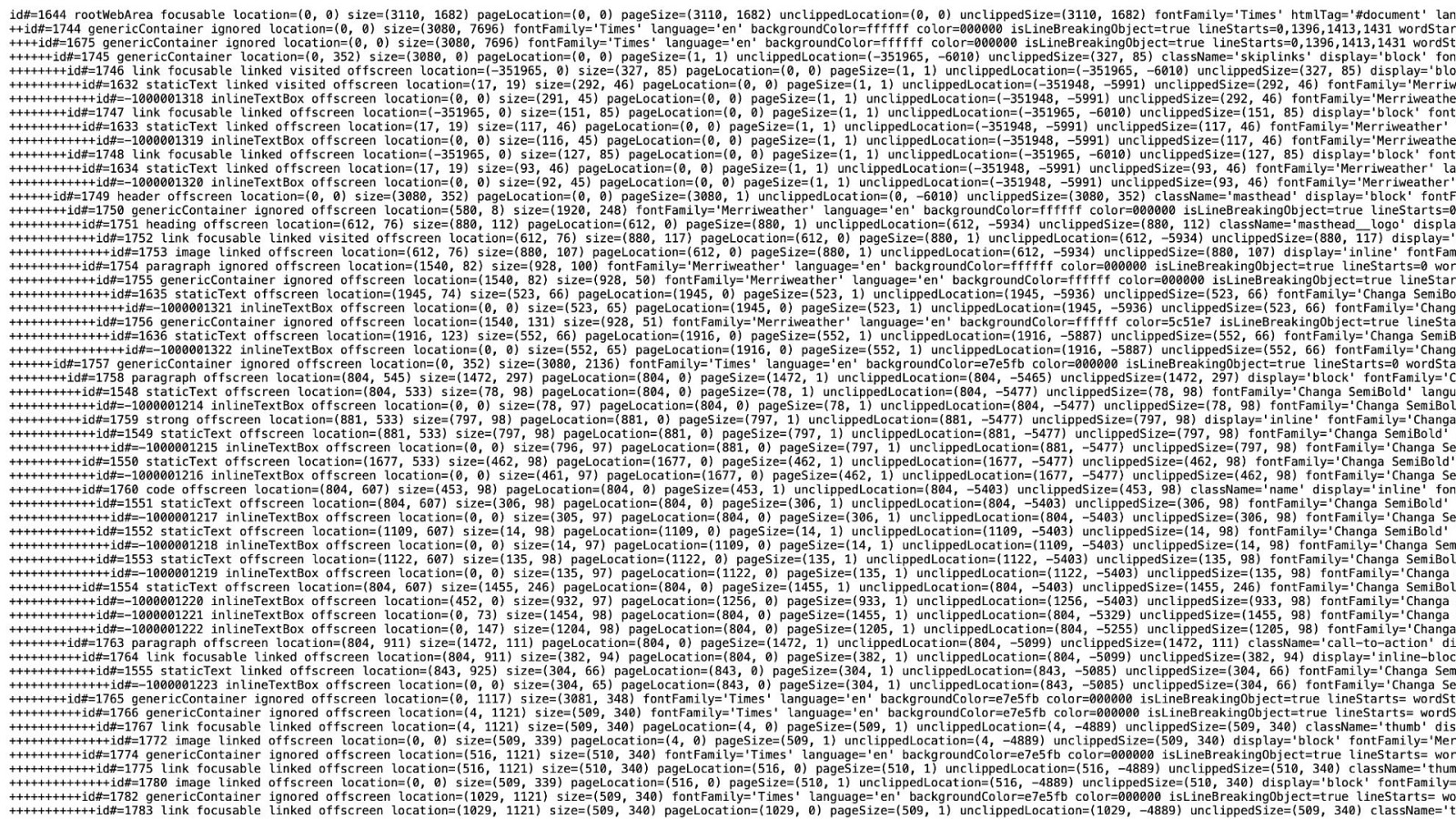

- And here’s an even more high fidelity example, a raw text dump of the Accessibility Tree for this same page

- This is an example of what the language might look like when we’re speaking machine directly to machine.

Slide 66

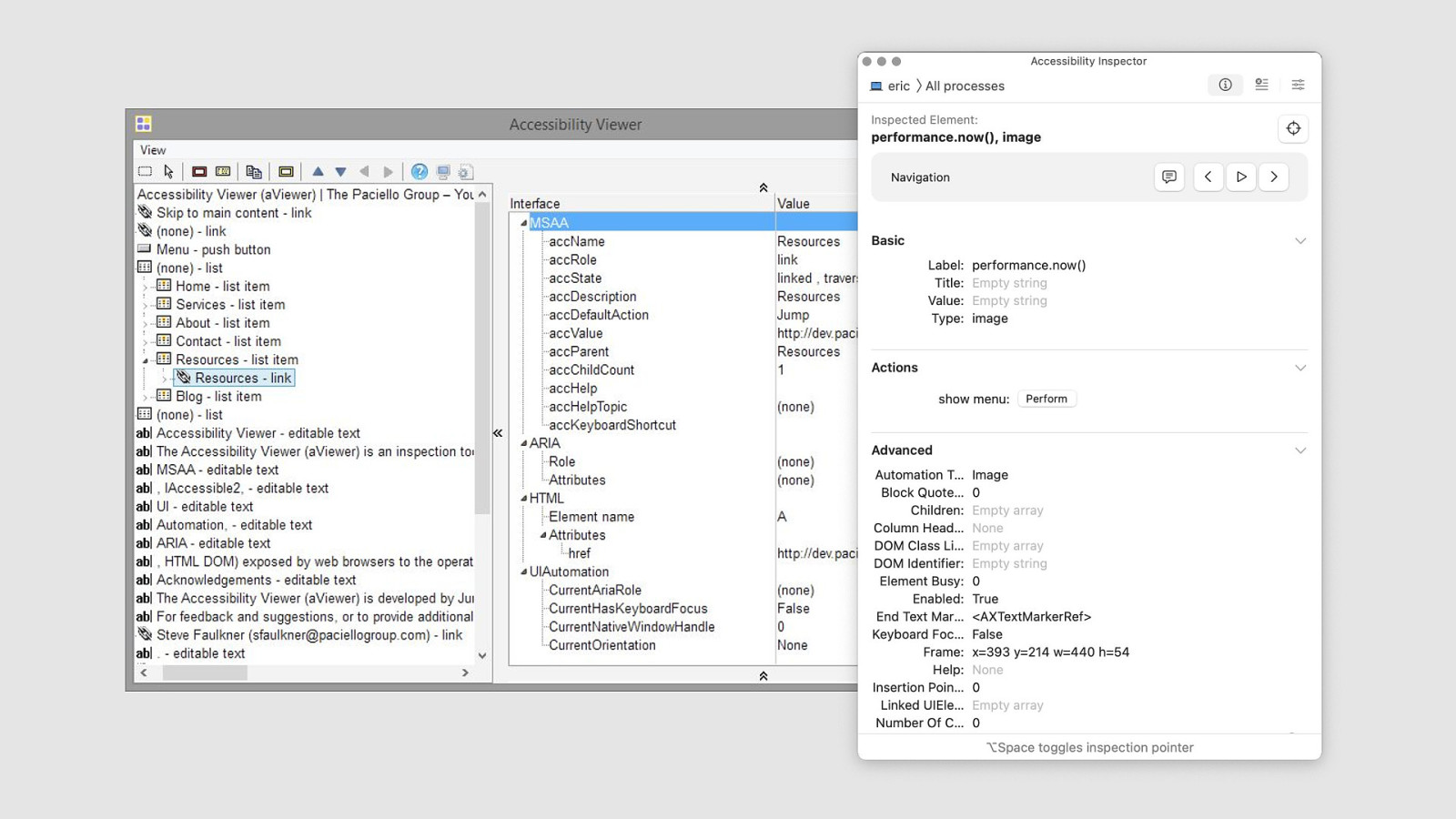

- We don’t speak machine directly, though

- Before we had Firefox’s Accessibility Inspector, we had to rely on more specialized tools to be the translators,

- The Paciello Group’s aViewer and Apple’s Accessibility Inspector are the two go-to resources

- And you’ll still need them if you want to inspect anything other than websites, or do some really serious digging

Slide 67

- So, with all that established, let’s make the abstract immediate

- What going on here, and why should you care?

Slide 68

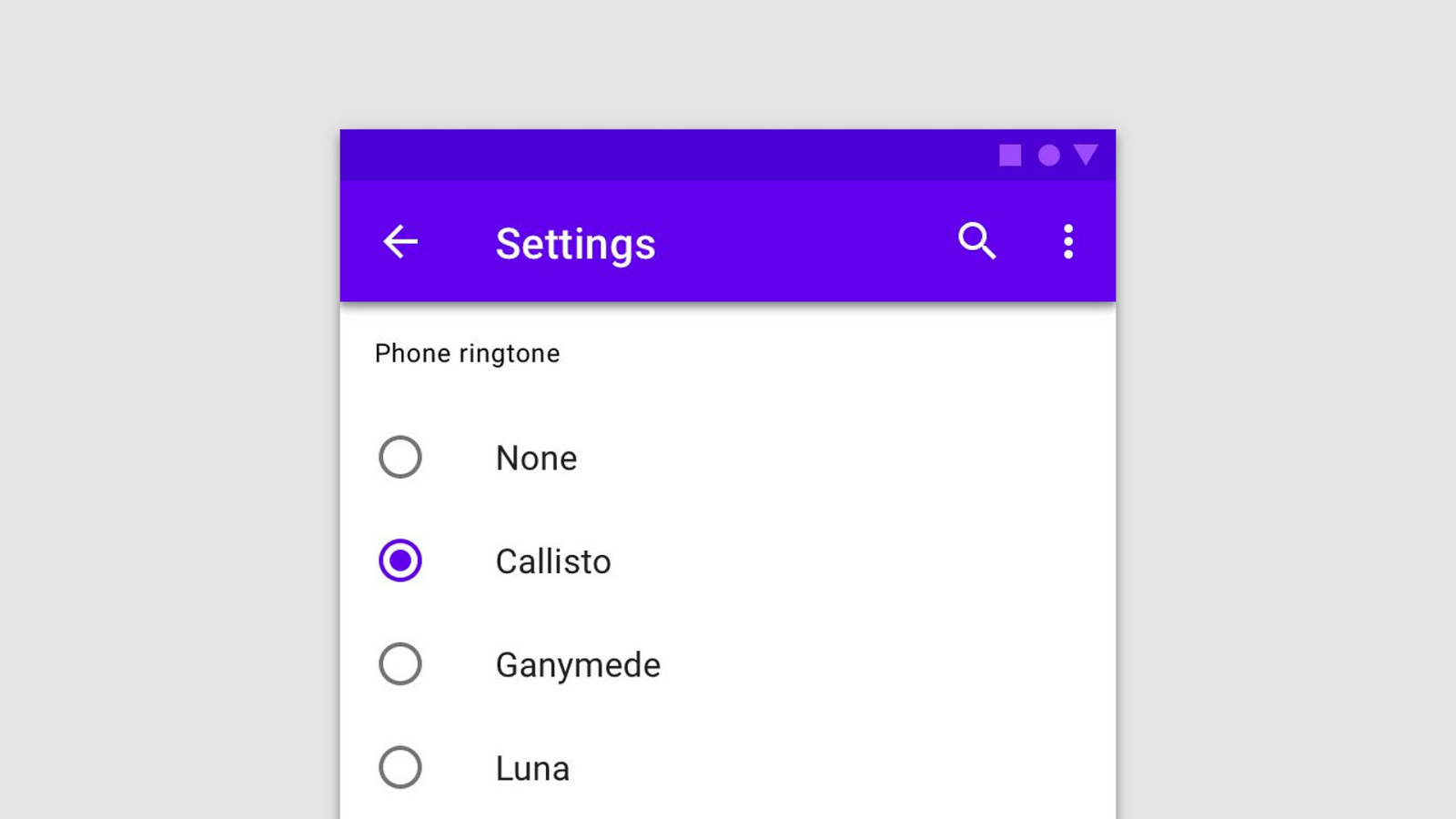

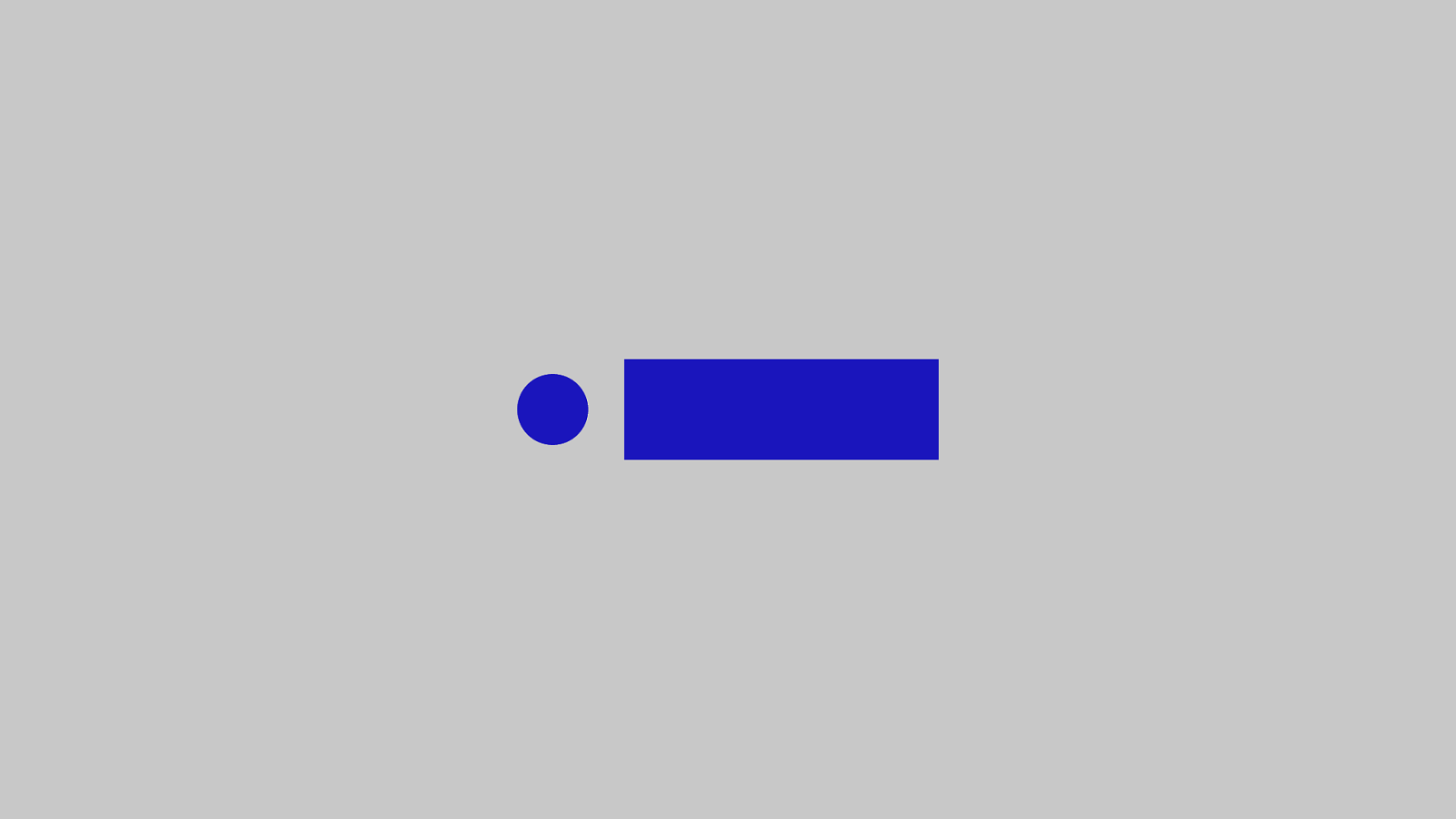

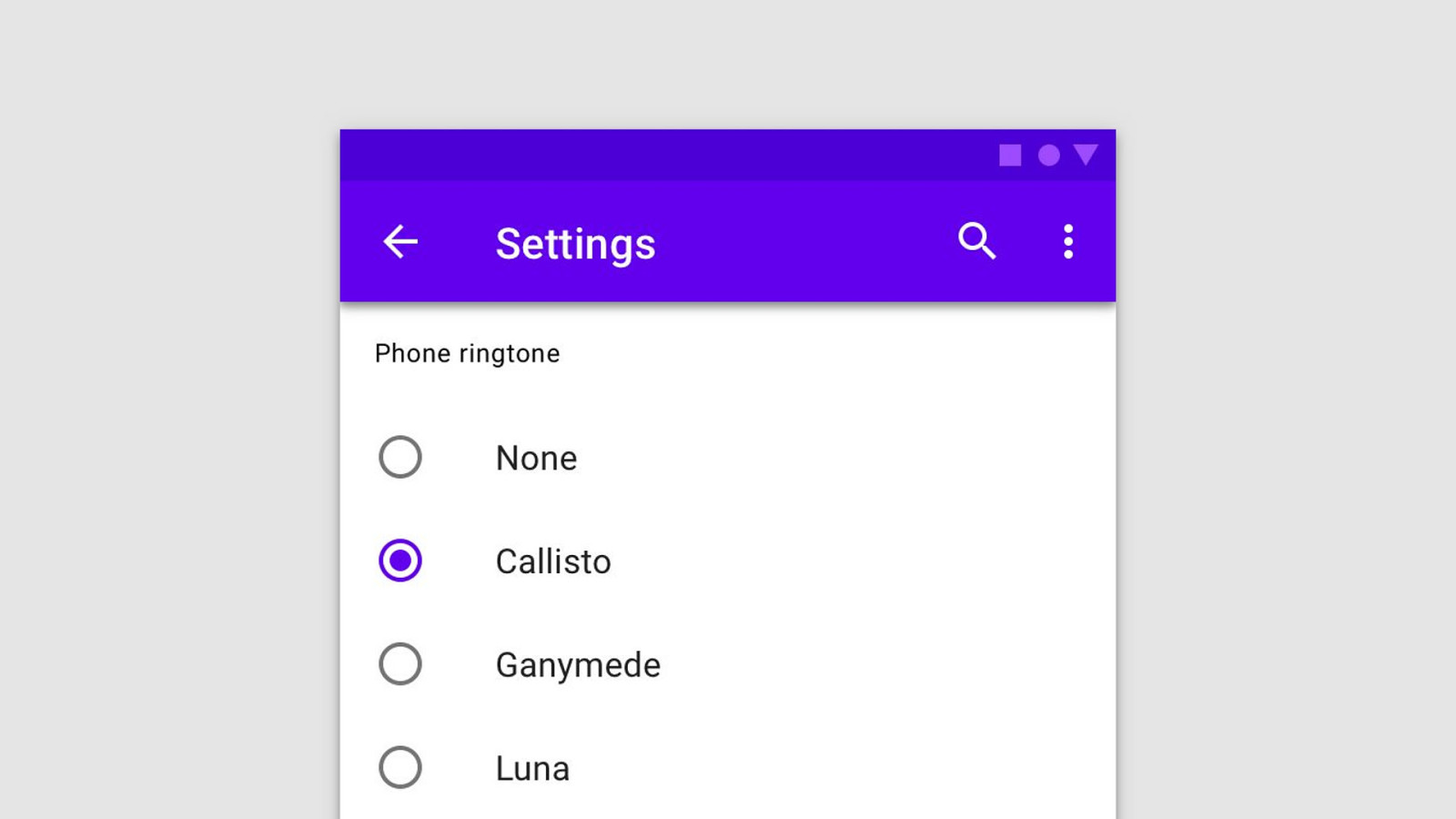

- With my auditing project, I narrowed the problem down to issues with Material Design’s radio inputs

- Here’s how these inputs appear visually

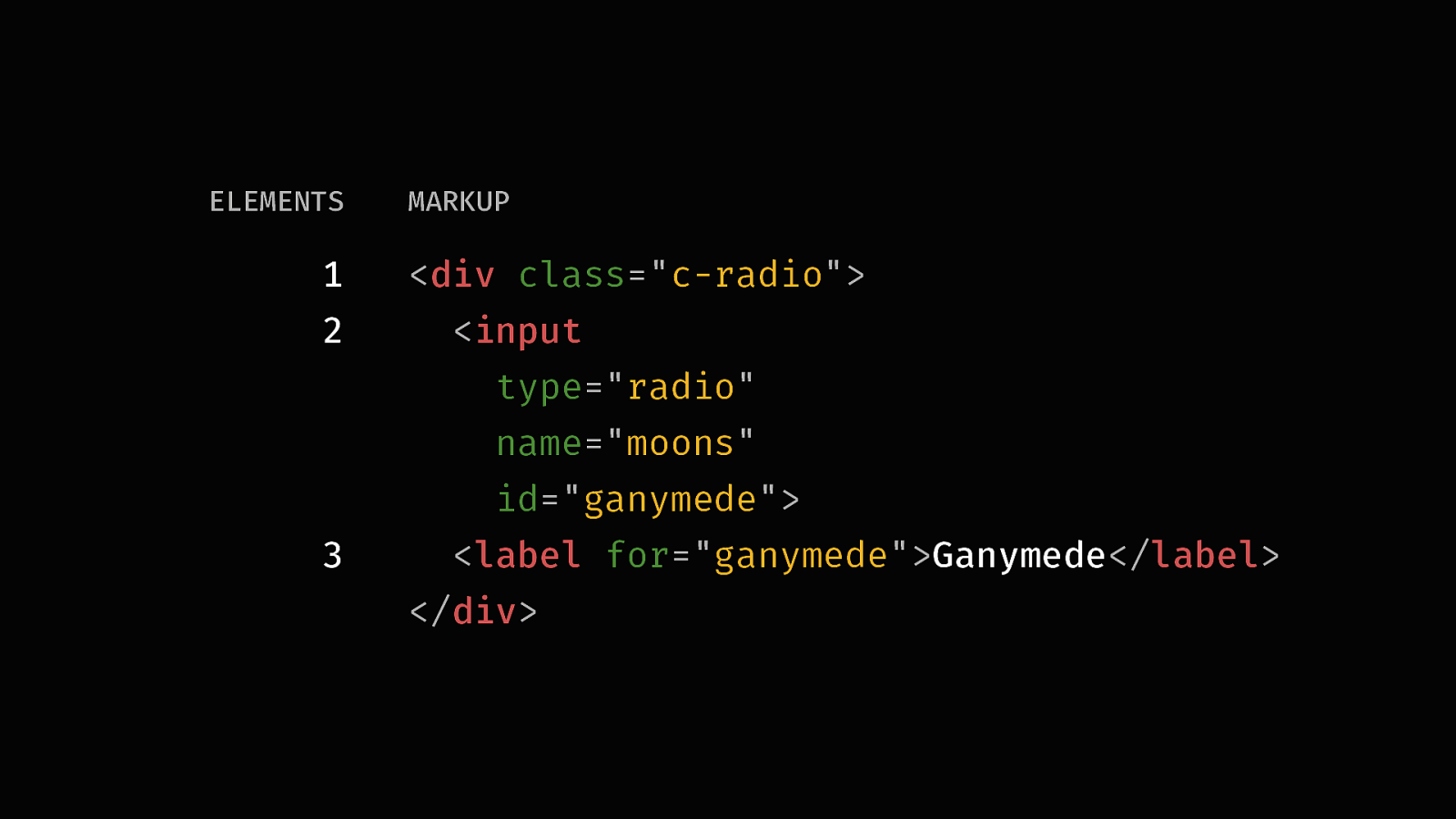

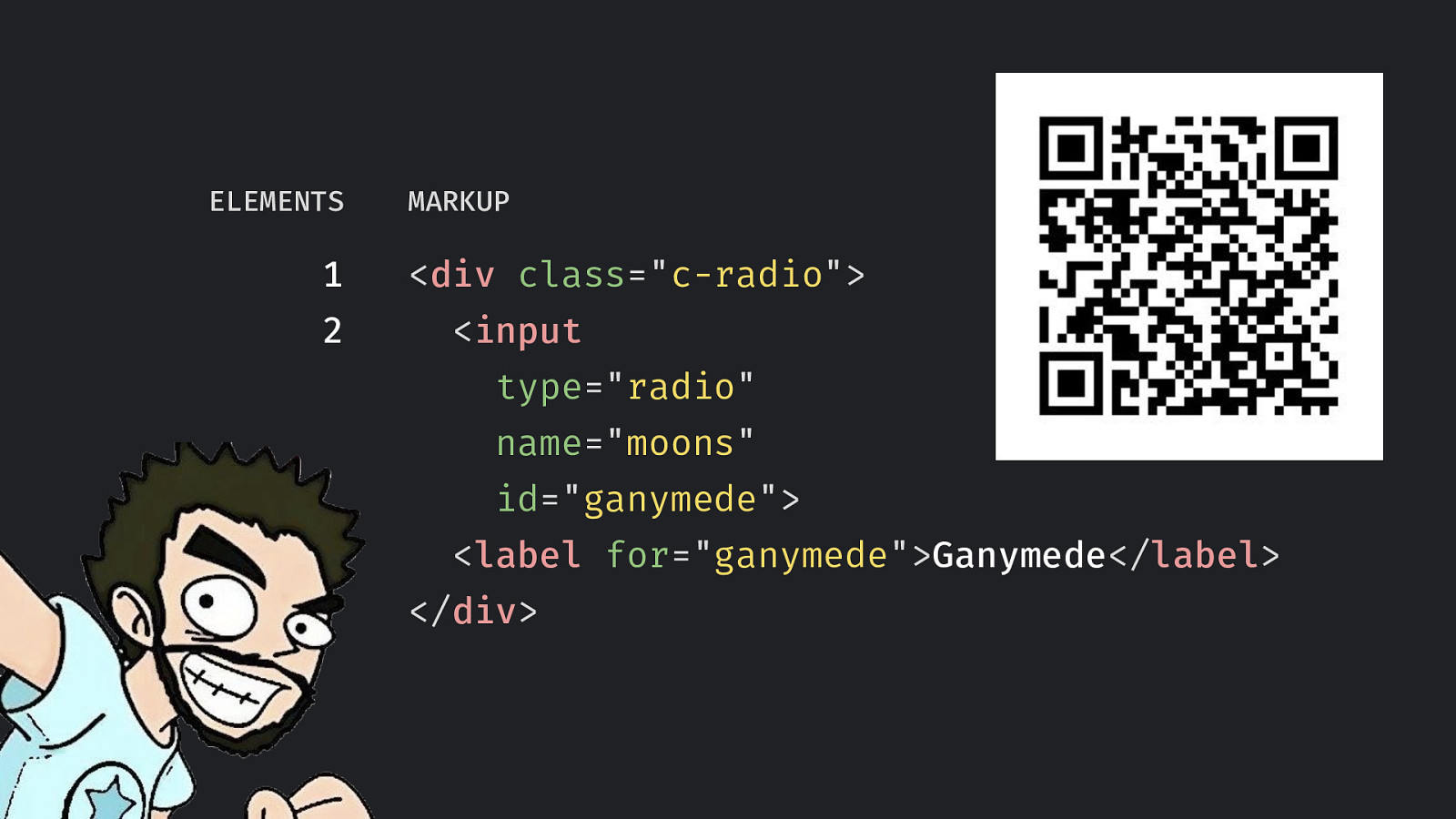

Slide 69

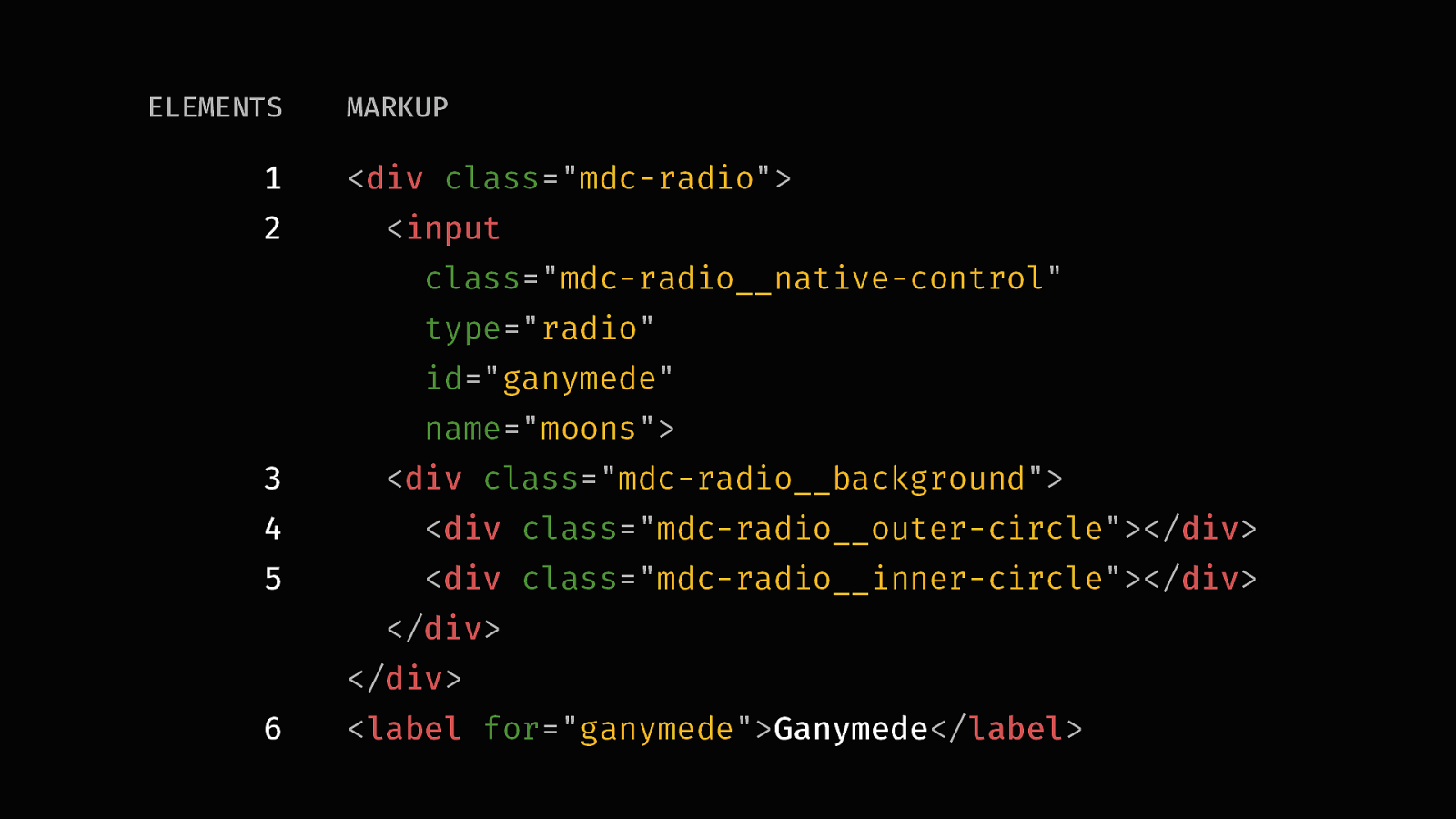

- And here’s how they appear in code

Slide 70

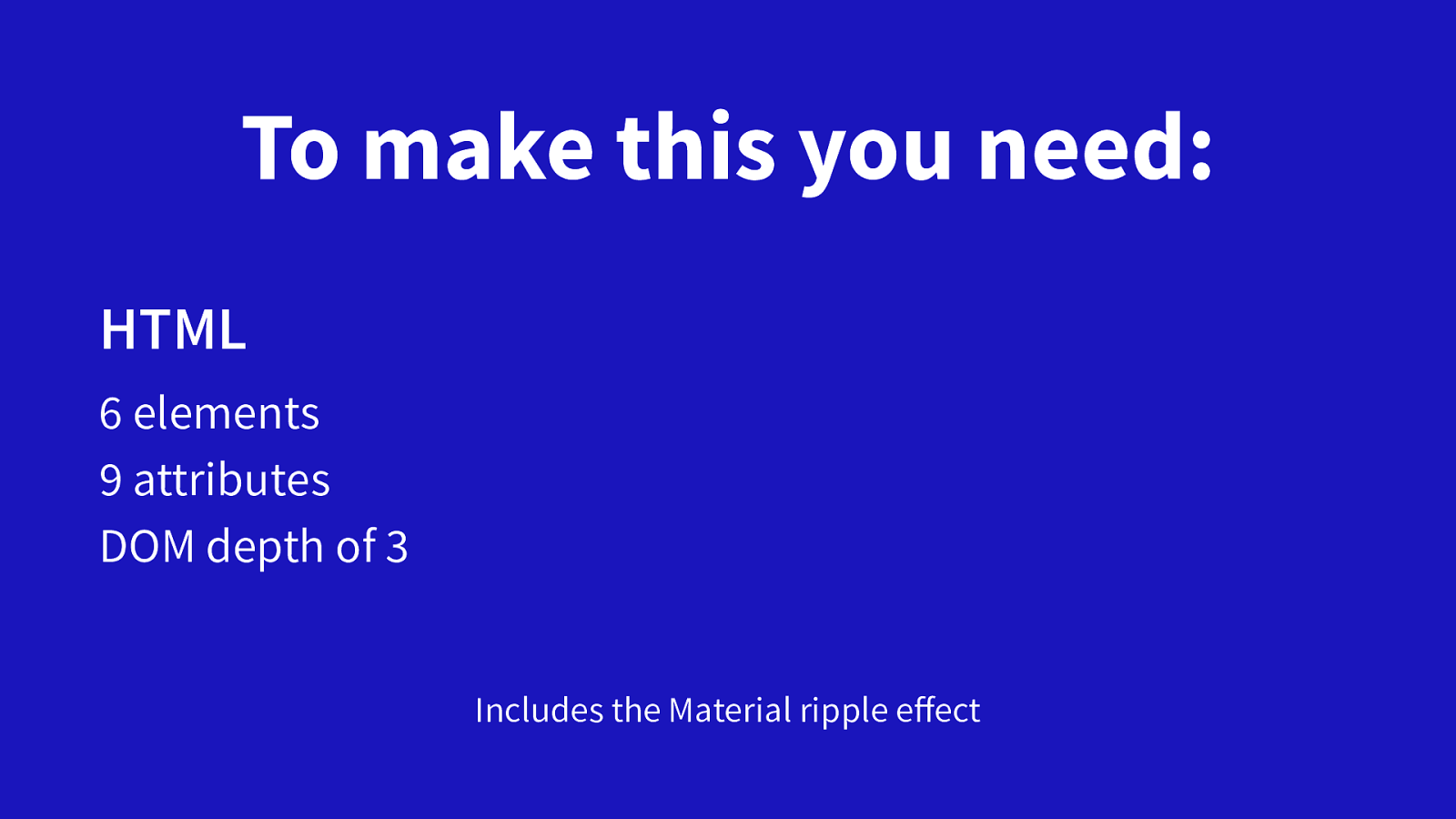

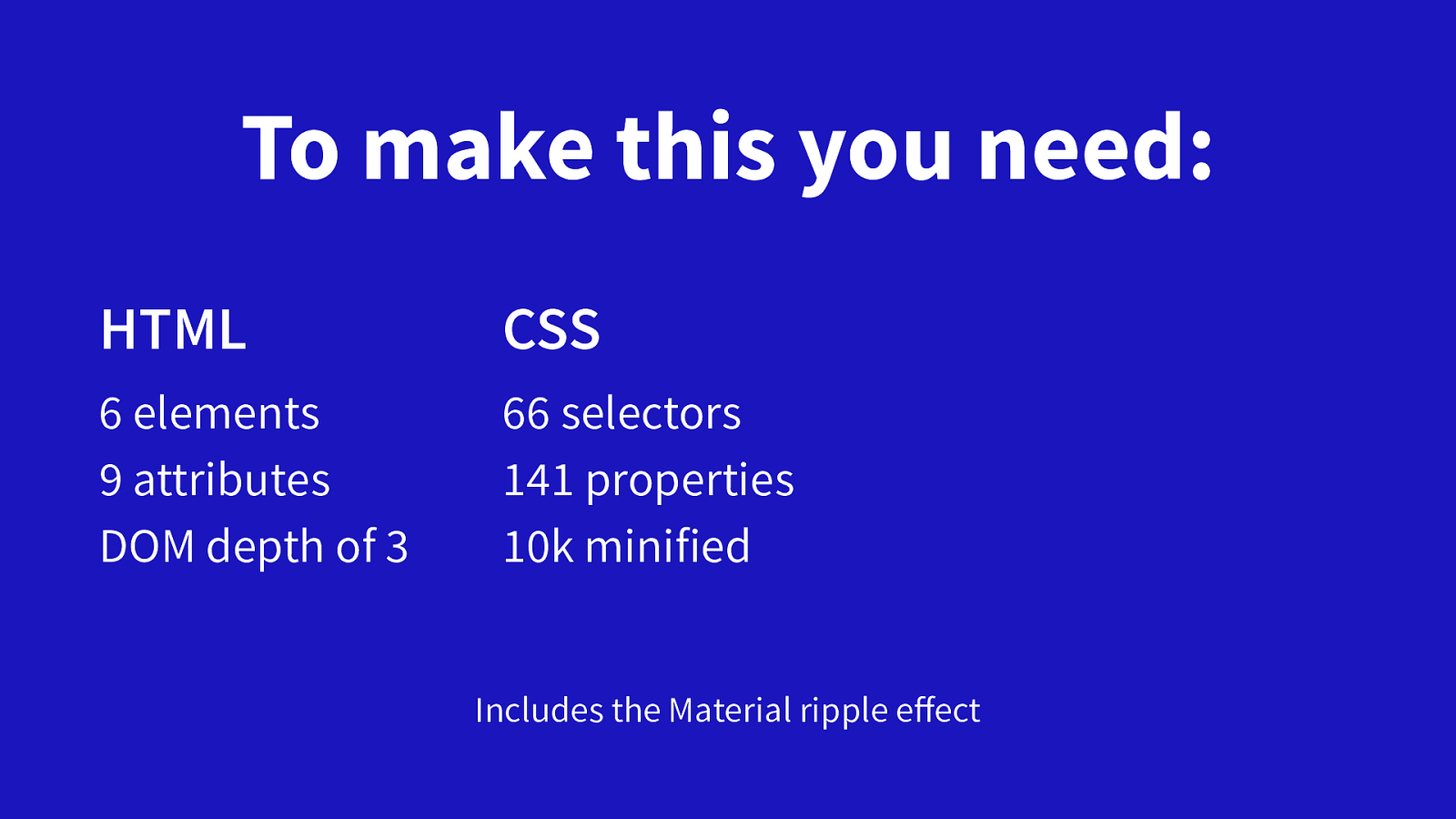

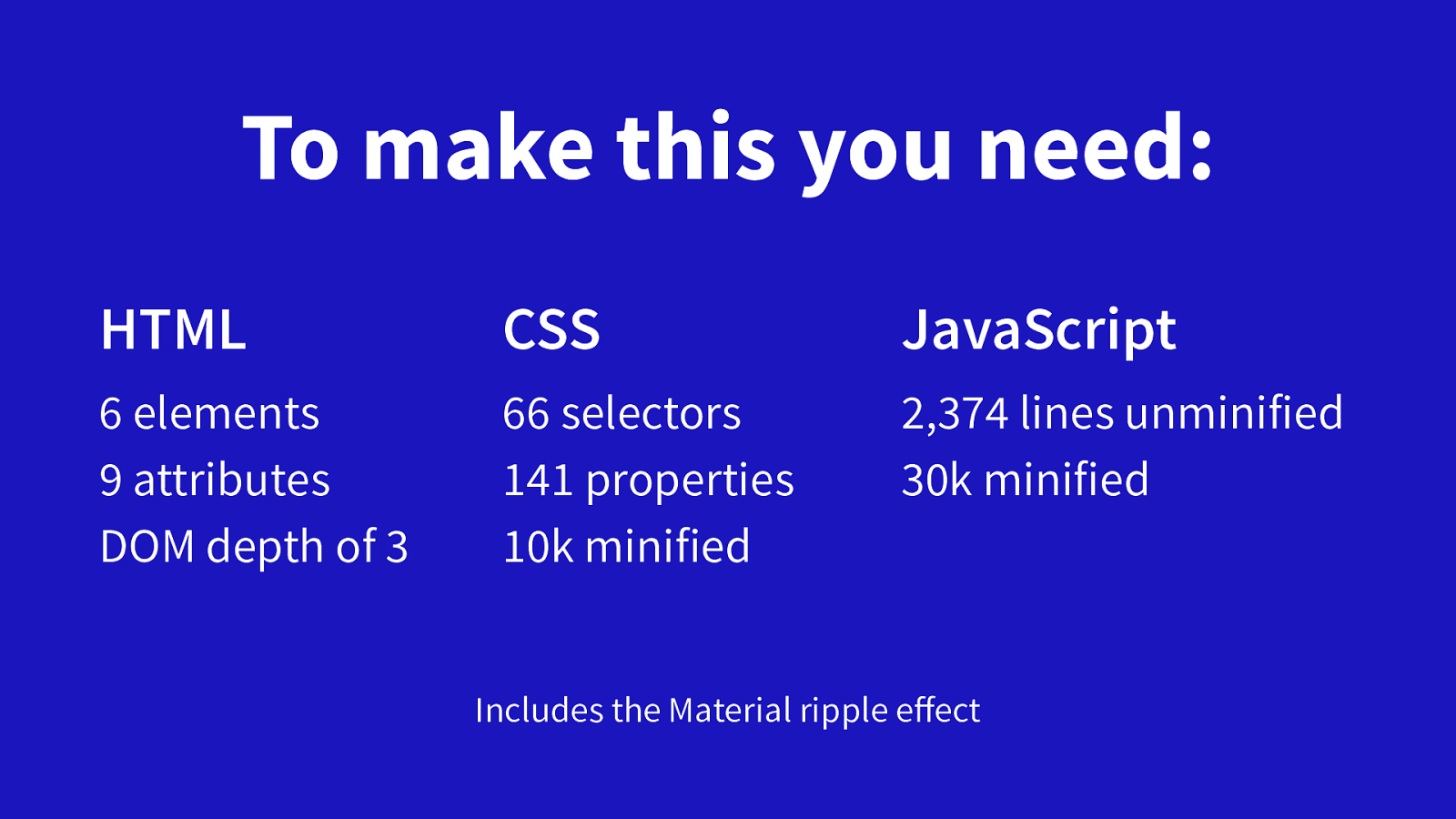

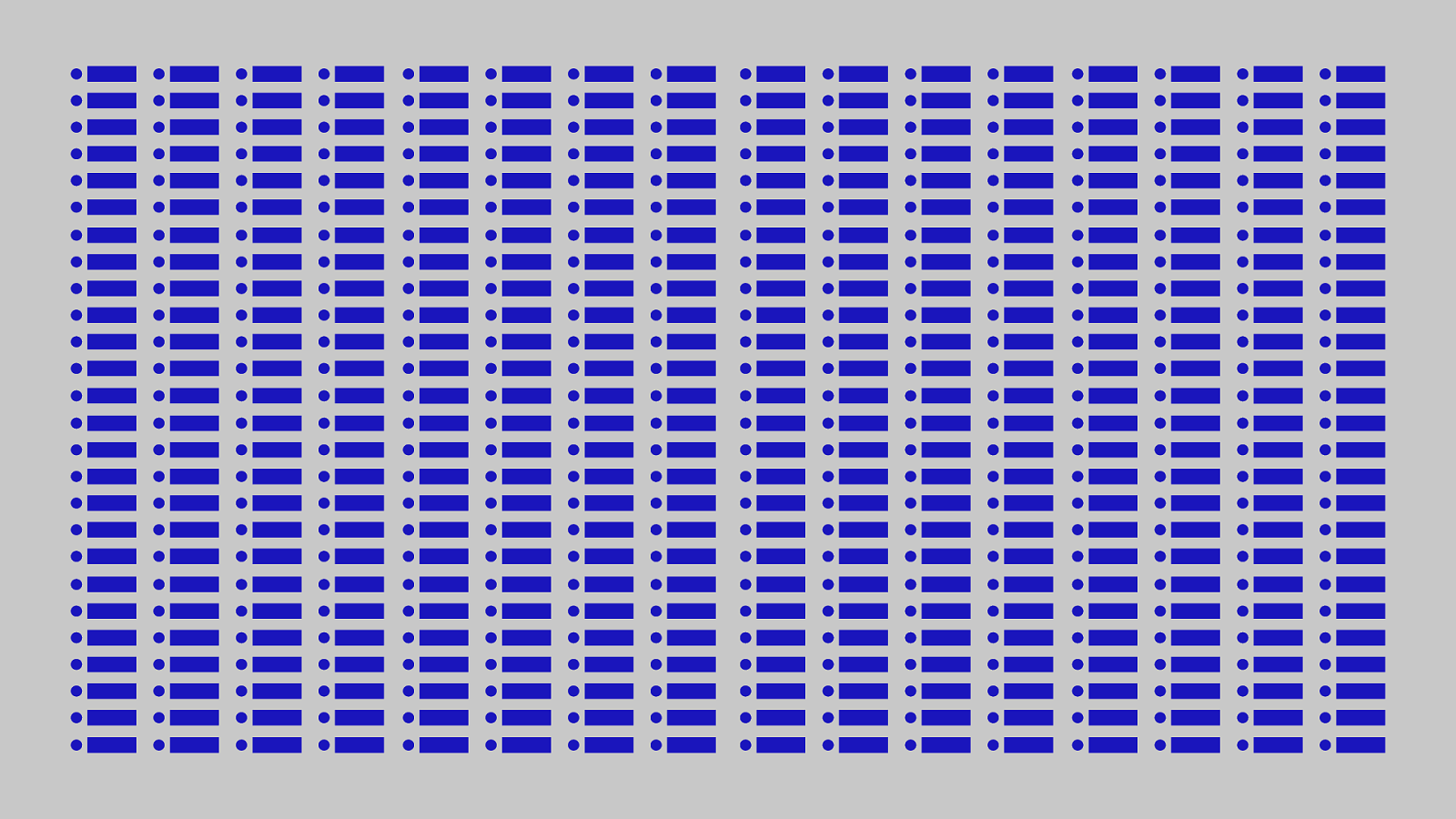

- To make a Material Design radio input, you need: six HTML elements containing nine attributes, with a DOM depth of 3

Slide 71

- You also need 66 CSS selectors containing 141 properties, which weighs in at 10k when minified

Slide 72

- You will also need 2,374 lines of JavaScript, which weighs in at 30k minified

Slide 73

- All that will get us a radio input

Slide 74

- But you need more than one radio input to be able to use it properly

Slide 75

- And oftentimes there’s a few options to select from

Slide 76

- Sometimes there’s more than just a few options

Slide 77

- And sometimes there’s even more than that

Slide 78

- In the case of my audit, we had a massive amount of radio inputs being conditionally injected into the page

- I can’t really do much here. It’s my job to bear witness and catalog access issues when acting as an accessibility auditor

- Which is partly why I switched over to becoming an accessibility designer instead

Slide 79

- The larger point being is that all of this all adds up if you are not paying attention

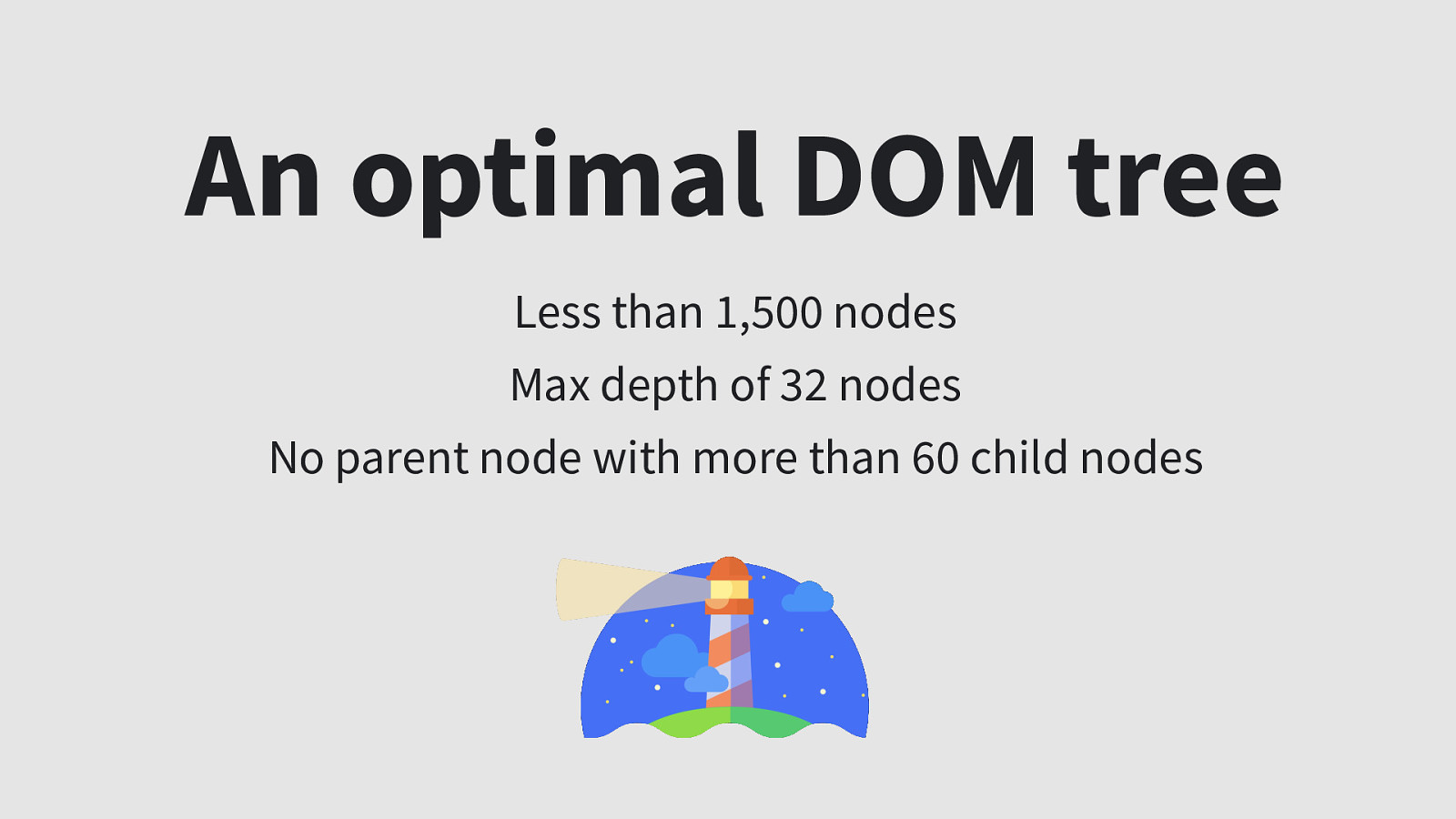

Slide 80

- Google’s Lighthouse recommends an optimal website DOM tree has:

- Less than 1,500 nodes

- Max depth of 32 nodes, and

- No parent node with more than 60 child nodes

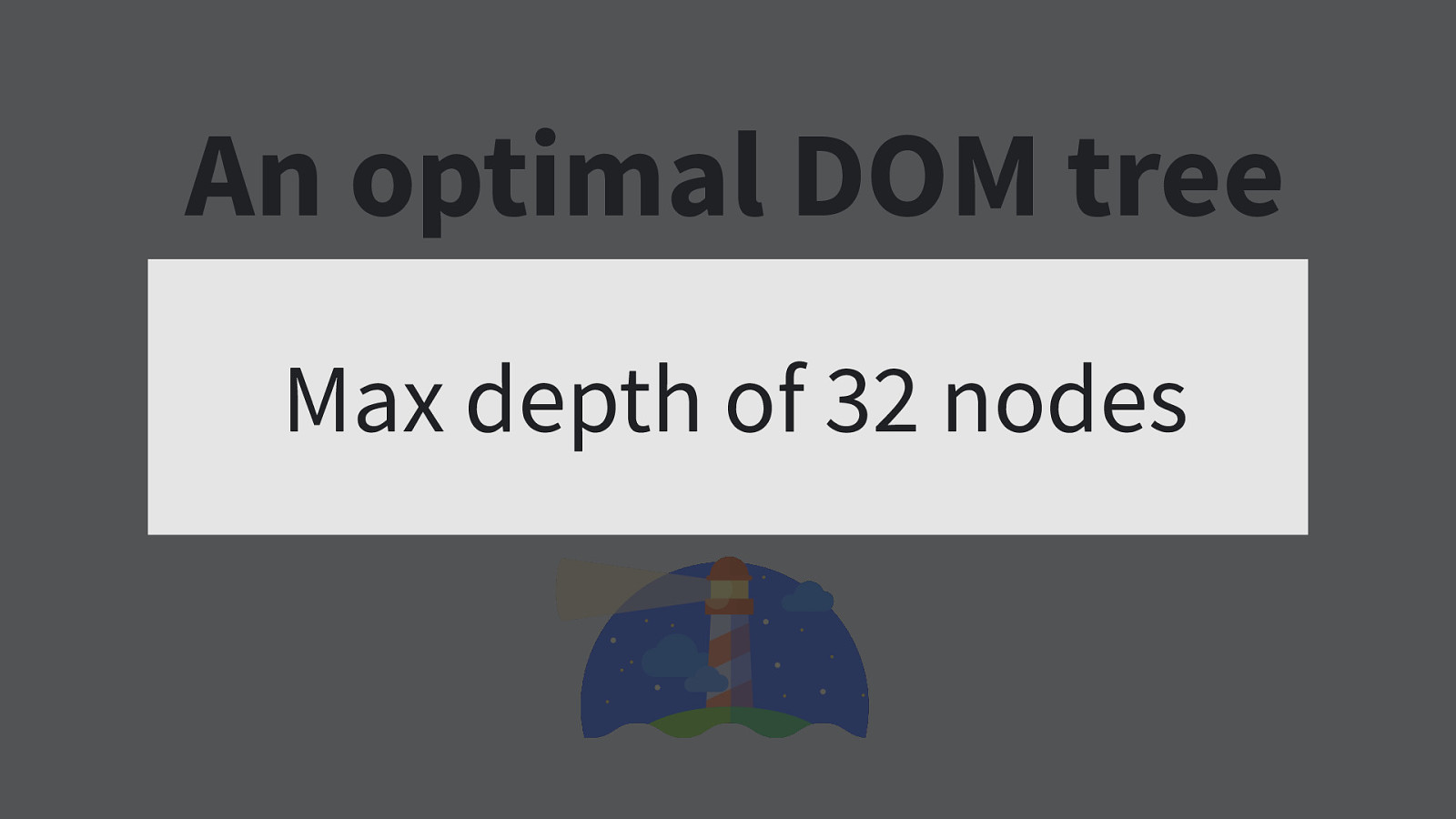

Slide 81

- What I’d like to call attention to is the max depth of 32 nodes bit

- That might seem like a lot of wiggle room at first, but take a moment and think about the templates of the sites you’ve worked on.

- There’s the frameset, wrapper divs, landmarks, components wrappers and if you’re doing it right, fieldsets on your forms

- Each digging a little bit more inward

Slide 82

- Another part of accessibility auditing is providing suggested fixes to the problems you uncover

- It’s tough work, but nobody likes to pay people money to tell them all the things that are wrong, but then offer no solutions

- We wound up recommending a radio input pattern that utilized three HTML elements

Slide 83

- It’s a pattern developed by my friend Scott O’Hara, taken from his excellent a11y_styled_form_controls project

- It’s worth saying that Scott puts these patterns through their paces, and tests them with an incredibly robust set of assistive technologies

- So a nice side benefit is knowing I can recommend this project to others with a great deal of confidence

[Q

Slide 84

- The updated radio inputs were completely visually indistinguishable from the original version

Slide 85

- And, to compare the two solutions on the code layer:

Slide 86

- We have a 50% reduction in HTML elements

and we cut the DOM depth down by a third

Slide 87

- There’s also a 30% reduction in CSS selectors and properties, resulting in the CSS payload for this component being reduced by 90%

Slide 88

- We’ve also completely removed 30k of JavasScript, which is 30k less blocking resource being served

Slide 89

- Cobbling up a rough prototype, we were able to create an environment that mimicked the conditions of the site we were auditing, only now using the new radio input code, and guess what?

Slide 90

- It worked! VoiceOver didn’t crash!

Slide 91

- So why is this our problem?

- Why should we care about the fragility of other people’s software?

Slide 92

- Well, prioritizing developer ergonomics without considering the generated HTML it produces can lead to bad things happening

Slide 93

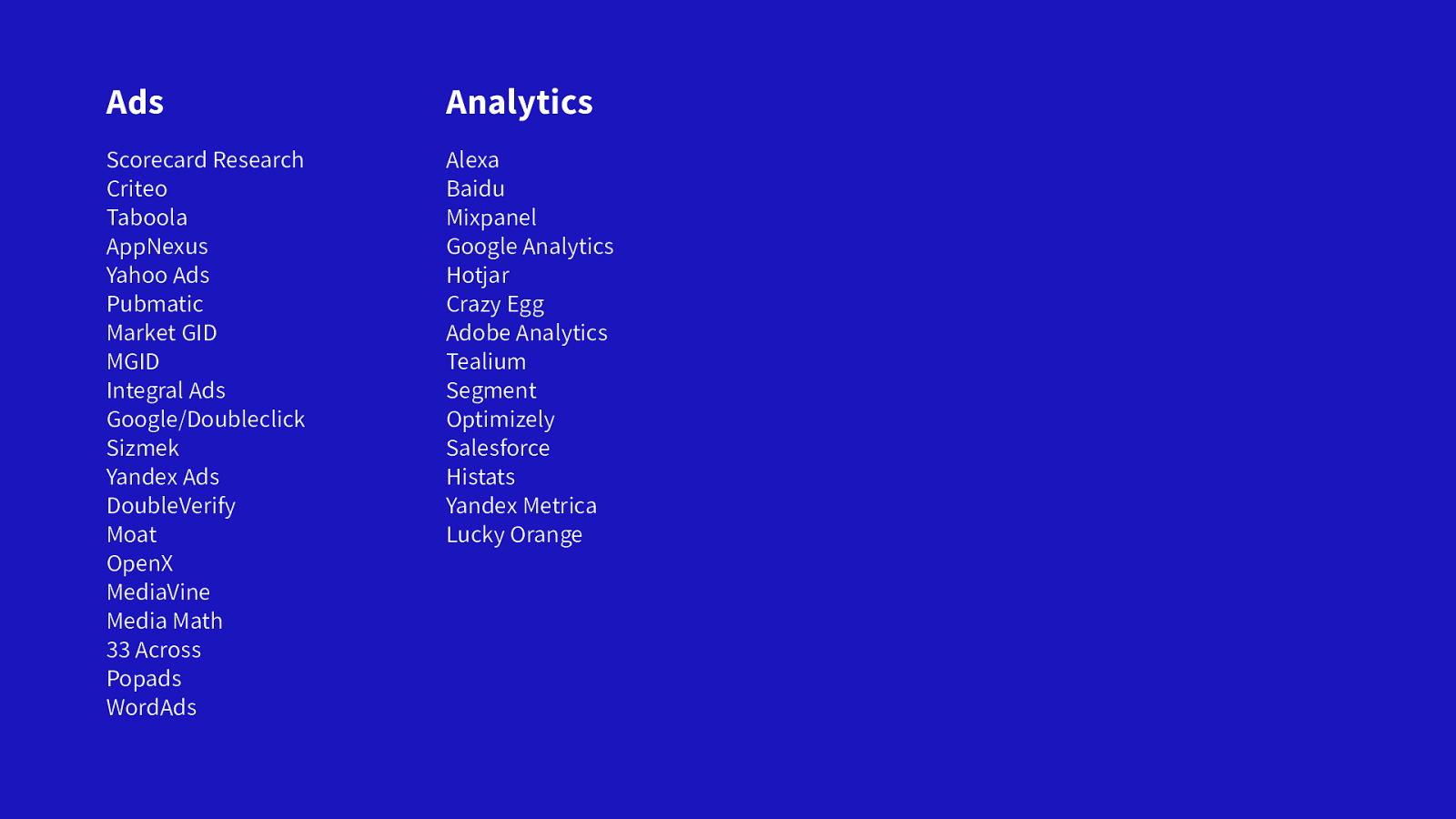

- And regardless of our setup, and despite our protests, we tend to get even more things piled on to our base experience

Slide 94

Slide 95

Slide 96

- Social marketing engagement tools

Slide 97

- Development integration utilities,

Slide 98

- And accessibility overlays

- If you are not familiar with what an accessibility overlay is, know this:

- They are predatory anti-solutions that prey on ignorance and fear of litigious action

- By offering a one line of code solution that promises to “fix” all your accessibility issues they all enable arbitrary third party JavaScript execution on your product, which should hopefully already set off some alarm bells in the audience

- And believe me when I tell you it’s some of the worst frontend code I’ve seen in my entire career

- AccessiBe is one of the worst offenders in the market, and has been repeatedly legally demonstrated to not deliver on what it promises

- In fact, I’ve given expert testimony to this effect, so believe me when I tell you I know what I’m talking about here

- Additionally, they refuse to comply with European Data Protection Impact Assessment requests, which is suspicious as hell

Slide 99

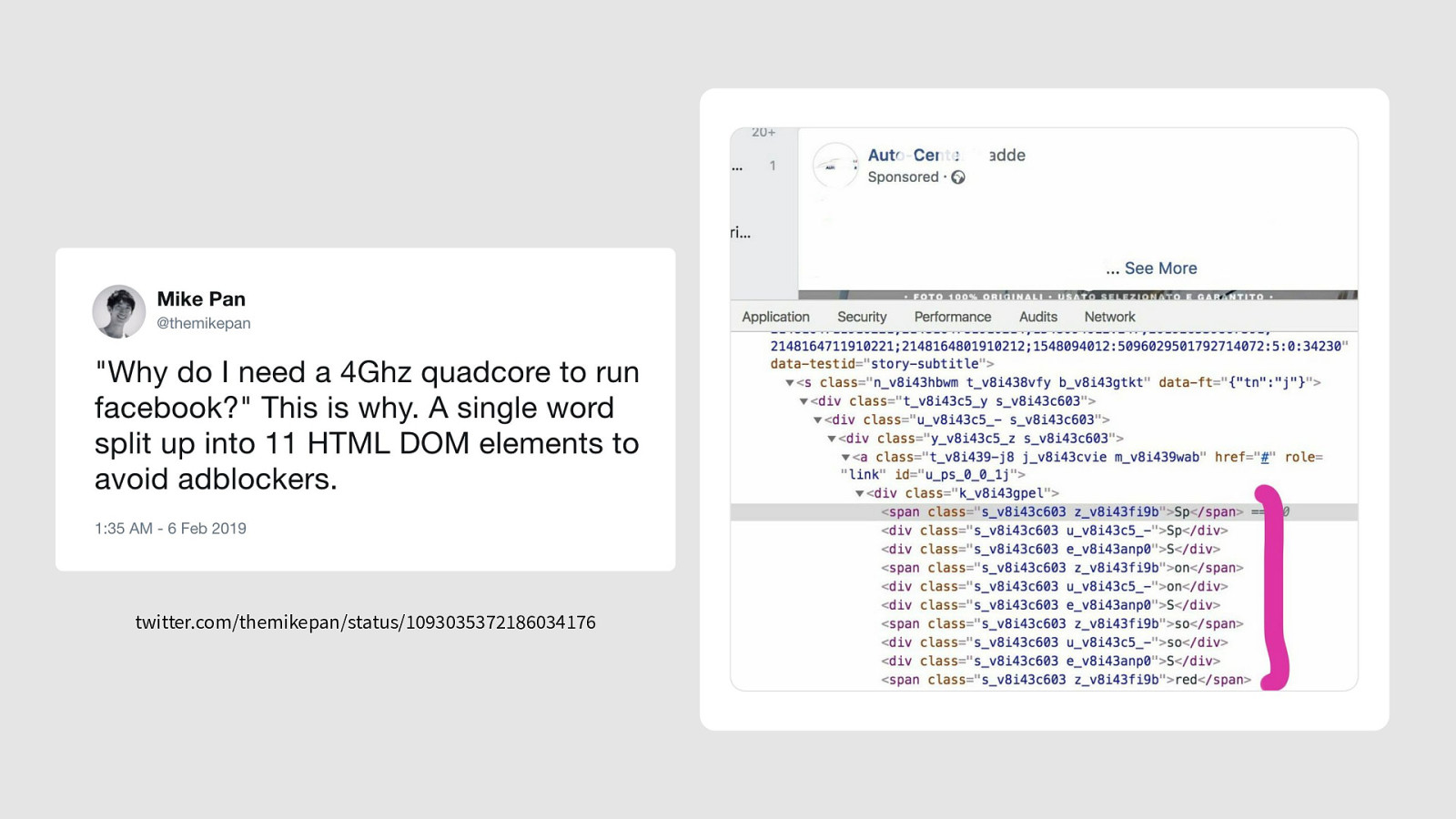

- And then there’s also the Cold War raging between websites and their users

- An example of this is Facebook splitting a single word into 11 DOM elements in order to thwart ad blockers

Slide 100

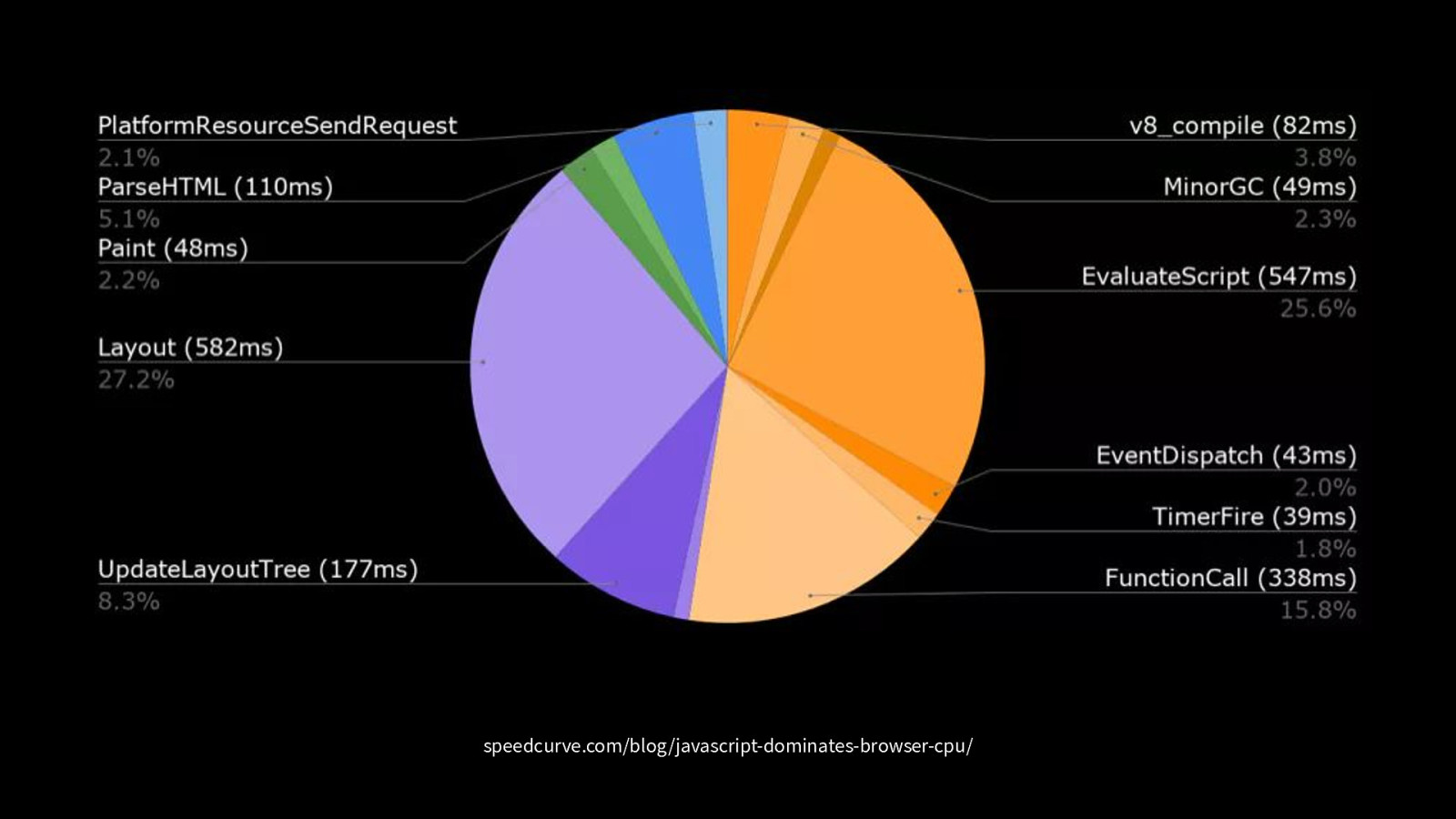

- And this graph, generated from the median values of how 1.3 million websites are generated, shows JavaScript claiming the majority of the share.

- This JavaScript majority means it’s that much more time spent blocking the browser from performing other other actions,

- Including things like interfacing with assistive technology

Slide 101

- The point here being is that we oftentimes don’t realize there are very real, very important things we sacrifice when we throw out what the browser gives us for free

Slide 102

- Here’s what Marco Zehe, Mozilla’s former senior Accessibility QA Engineer has to say about all this:

- Nibbling away at those milliseconds it takes for information to reach assistive technologies when requested. My current task is to reduce the number of accessible

objects we create for html:div elements. This is to reduce the size of the accessibility tree.

Slide 103

- This reduces the amount of data being transferred across process boundaries. Part of what makes Firefox accessibility slower on Windows since Firefox Quantum is the fact that assistive technologies now no longer have direct access to the original accessible tree of the document.

Slide 104

- A lot of it needs to be fetched across a process boundary. So the amount of data that needs to be fetched actually matters a lot now. Reducing that by filtering out objects we don’t need is a good way to reduce the time it takes for information to reach assistive technologies.

Slide 105

- This is particularly true in dynamically updating environments like Gmail, Twitter, or Mastodon. My current patch, slatted to land early in the Firefox 67 cycle, shaves off about 10 to 20% of the time it takes for certain calls to return.

Slide 106

- Note that all this optimization is only for one browser, Firefox

Slide 107

- And that there are a lot of browsers out there

Slide 108

- It’s also not all about browsers, either.

- Here’s a refreshable braille display, one of many other kinds of assistive technology

- They are purpose-built, low power, high efficiency devices that many blind people use to read the web

- Think of them kind of like Bluetooth speakers in terms of how they connect to computers, smartphones, and tablets, and how much horsepower they have under the hood to use

- Refreshable braille displays also interface with the accessibility tree in order to spell out content,

- But, as previously mentioned, have far less computational power than a laptop or smartphone

- This means that they can be especially susceptible to failing to work when an experience is too non-performant

Slide 109

- So, you know, let’s say I’ve successfully pled my case here

- To which I hear, “Someone should do something!” The battle cry of bystanders everywhere

- Let’s pragmatically unpack this some, and figure out what our actual, available options are

Slide 110

- For screenreaders, the main ones are JAWS

Slide 111

- And NVDA

- Both are Windows screen readers

Slide 112

- There’s also VoiceOver for macOS and iOS

Slide 113

- And Talkback for Android

- These are the big four screen readers you’re going to hear about

- It’s sort of analogous to Chrome, Safari, Edge, and Firefox

- In that there’s more screen readers out there, but these cover the main use cases you’re most likely to deal with

- While not all assistive technology are screen readers, if your site works well for them, chances are good it’ll work well for other forms of assistive tech

Slide 114

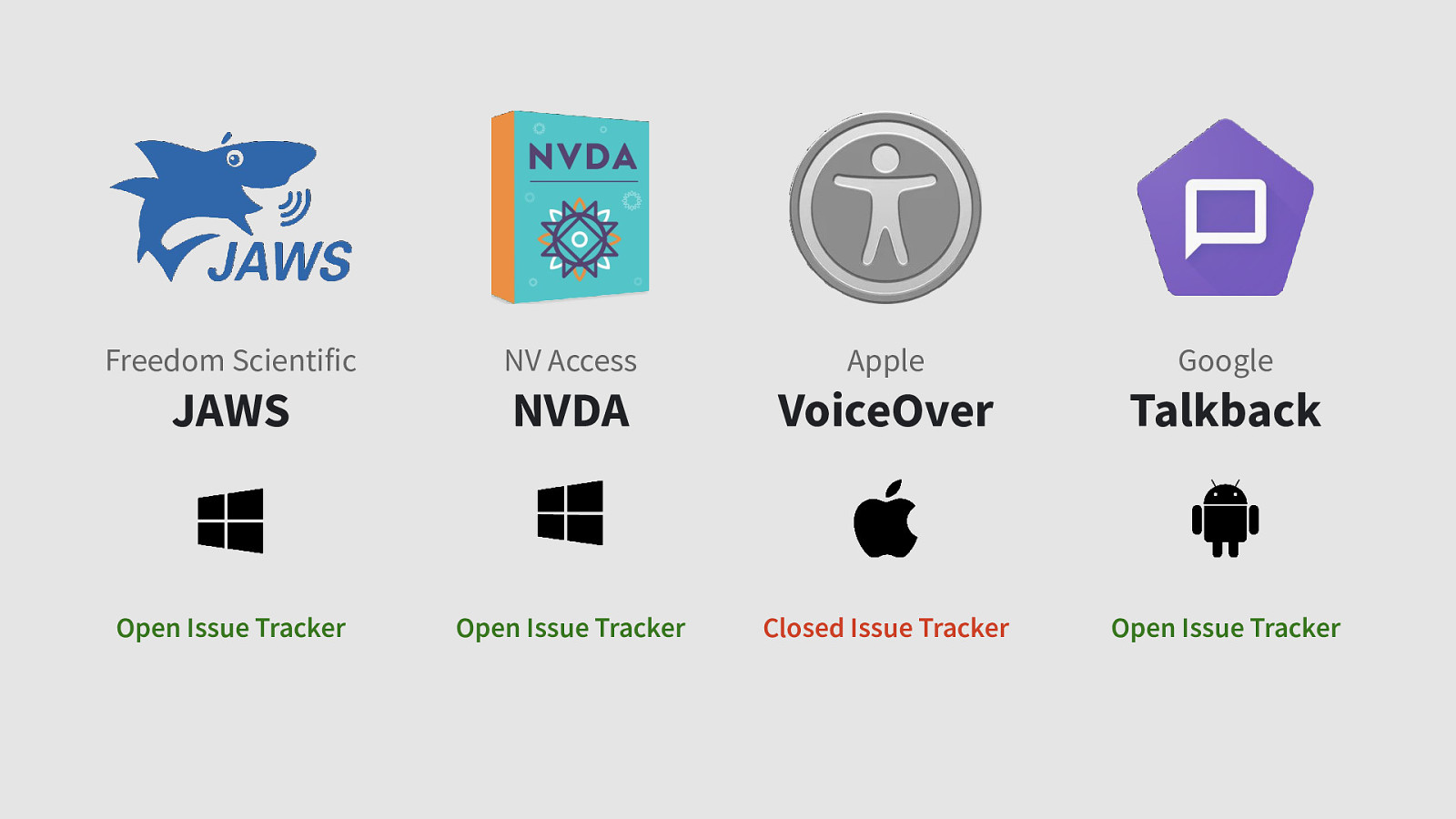

- Of them, all but one have an open issue tracker

Slide 115

- But half have closed source code

- This means that while we can file issues, we aren’t really empowered to do much more about it on the assistive technology layer

- I think it’s also completely unrealistic here to expect people to submit and follow issues or code pull requests across all trackers in addition to working a full-time job

Slide 116

- We also don’t always know what is going to be prioritized and when.

- Remember, assistive technology has to pay attention to the whole operating system, so your website’s current burning priority may not be the assistive technology manufacturer’s.

- And as the previous slide demonstrated, sometimes we also can’t know what their own particular burning priorities are.

- Because of this, our only other realistic option is to keep the DOM trees on our sites nice and shallow, and our JS payloads light

- And there are actual, tangible benefits to doing so

Slide 117

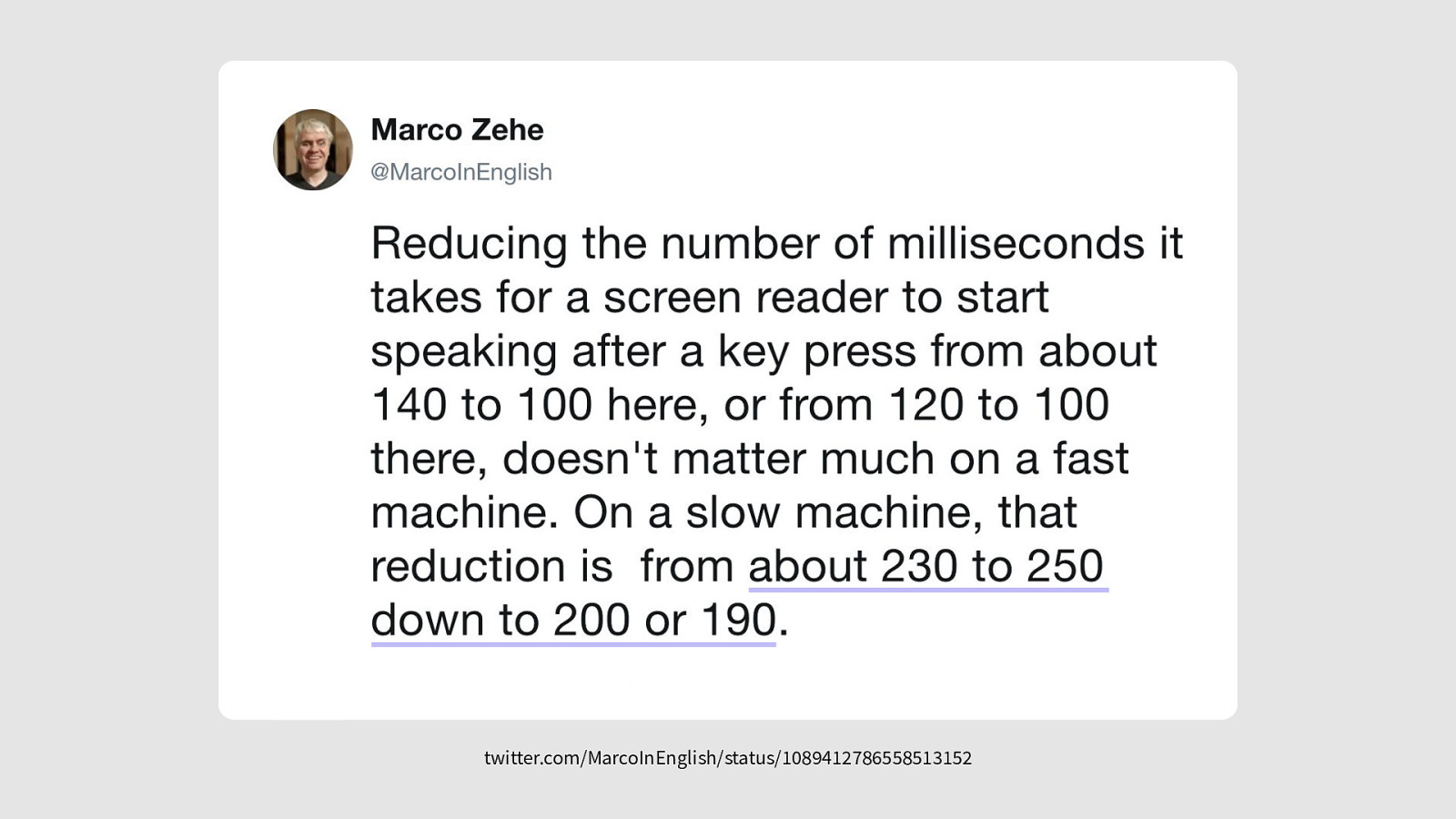

- Here’s Marco again weighing in again on his optimization efforts:

- Reducing the number of milliseconds it takes for a screen reader to start speaking after a key

press from about 140 to 100 here, or from 120 to 100 there, doesn’t matter much on a fast machine. On a slow machine, that reduction is from about 230 to 250 down to 200 or 190.

Slide 118

- So now let’s talk about what a slow machine means

- If you are disabled and/or underserved, you face significant barriers to entering and staying in the workforce

- This means you may have less access to current technology, especially the more expensive, higher quality versions of it.

- Another factor is some people who rely on assistive technology are reluctant to upgrade their software, for a very justified fear of breaking the way they use to interact with the world

- This includes the assistive technology they use, as well as the browser and operating system it interfaces with

Slide 119

- Slow machines may also not mean an ancient computer

- Inexpensive Android smartphones are a common entry point for emerging markets and underserved communities, and with Android comes Talkback

Slide 120

- A slow machine might also come from a place you may not be expecting

- By which I mean you might have a state-of-the-art computer, and are doing state-of-the-art things on it

- This requires a ton of computational resources, which makes fast things slow

- With less computational resources to go around, we may have unintended consequences, possibly re-creating a situation similar to our too many radio inputs problem

Slide 121

- Think Electron apps, desktop programs that are built with web technologies

- On this slide we’ve got a few of the more popular Electron apps out three, including 1Password, Teams, Slack, Figma, VS Code, and Discord,

- Many of which can be running concurrently

Slide 122

- Accessibility auditing isn’t something people normally do out of the goodness of their own heart.

- It’s typically performed after a lawsuit has been levied against an organization

- And let me be clear: when you create inaccessible experiences, intentionally or not, you are practicing discrimination

- The upcoming European Accessibility Act acknowledges this, and will put protections in place starting next year to help ensure people cannot be discriminated against based on their disability conditions

- Similarly, the Americans With Disabilities Act already guarantees these protections

- This extends to both private organizations and the digital space, and its language is couched in Civil Rights, which are some of the strongest protections individual citizens have in the United States.

- This legislature is a good thing, as it guarantees protections as more and more of the services necessary to living life go online.

Slide 123

- You need to work with what you have, not what you hope will be

- Part of this means understanding that when we want things to be better we need to understand that these kinds of changes are really technically complicated under the hood, as well as spread across multiple concerns,

- Each with their own priorities, agendas, and resourcing

- On top of that, accessibility fixes are often viewed as unglamorous and deprioritized compared to other features

Slide 124

- I don’t mean to bum you out, and I don’t expect you to become accessibility experts

- However, as people who are interested in more than just the surface level of things, you are uniquely empowered to affect positive change

- What I ask of you is to at least incorporate basic accessibility testing into your workflows

- If anything, just check to see if a screen reader crashes when you’re auditing a particularly gnarly performance issue.

- After all, a bad assistive technology experience is better than none at all

Slide 125

- “But Eric” you say! “Accessibility is scary and I’m afraid I’ll misrepresent something.”

- Don’t worry, friends! I’m going to teach you how to do what I did

Slide 126

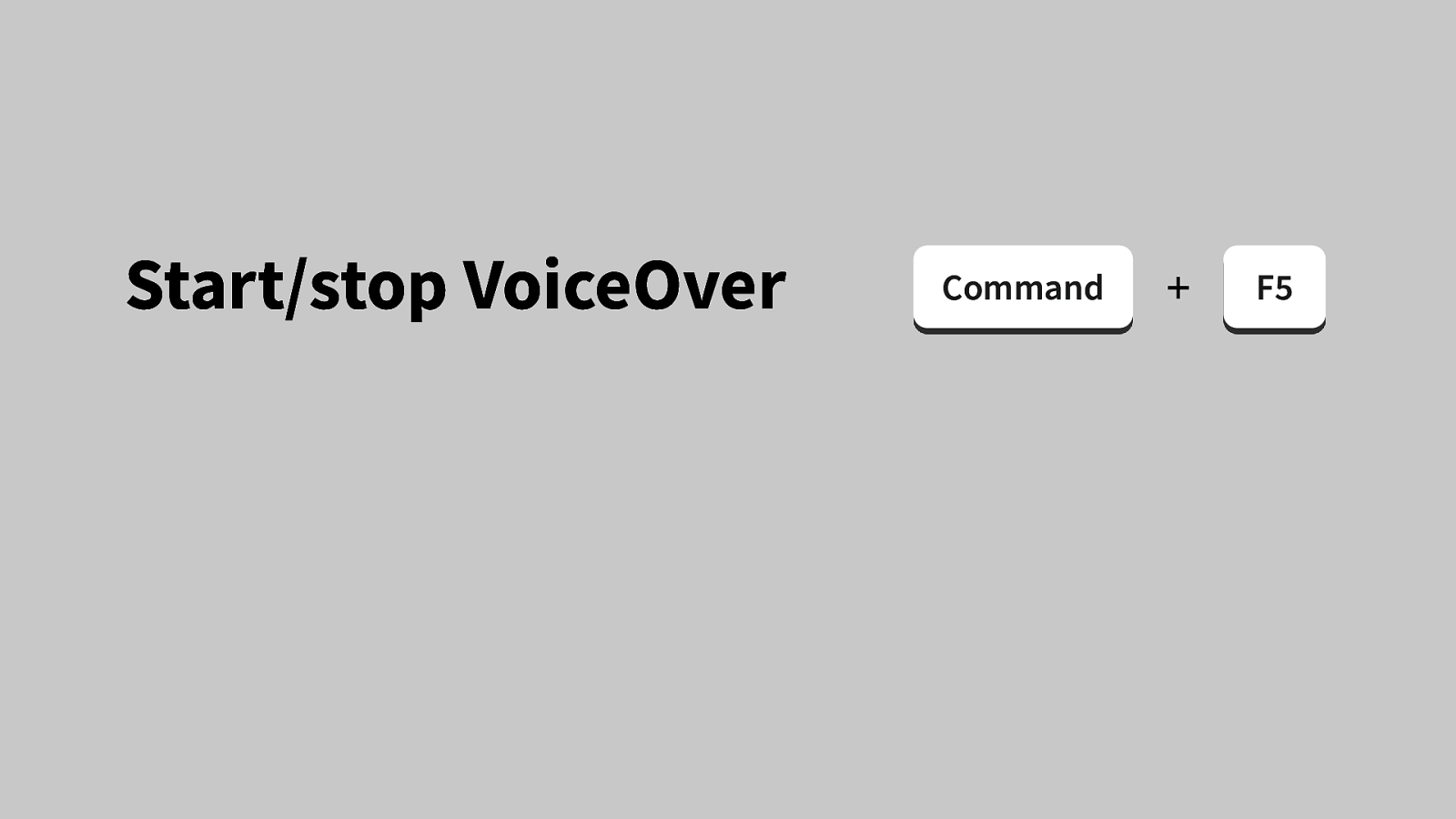

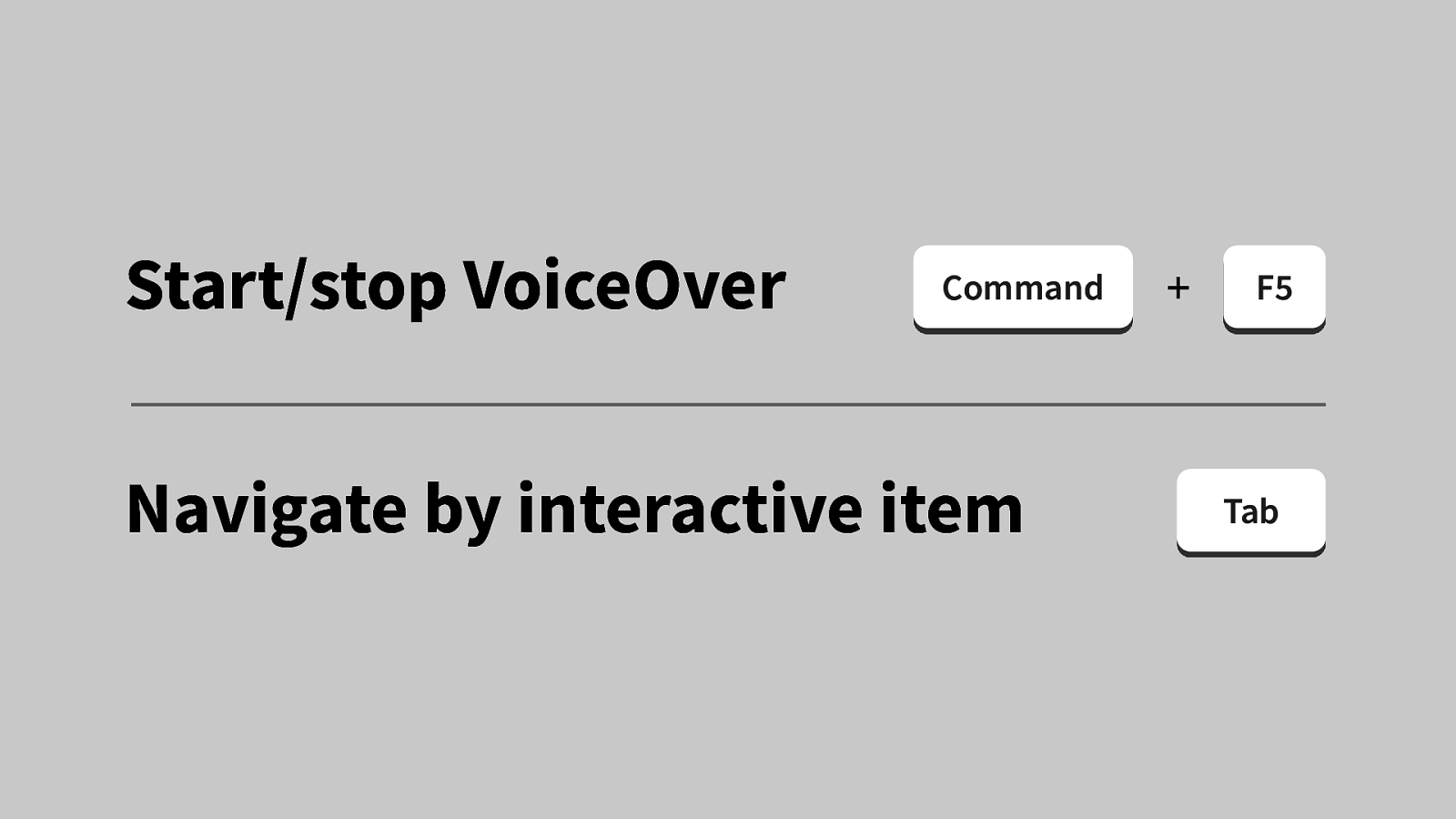

- If you’re using a Mac, you can start VoiceOver by pressing Command F5

Slide 127

- Then you hit tab to navigate by interactive item

- And shift plus tab moves you backwards by interactive item, if you’re feeling adventurous

- Then you tab around your website or web app

Slide 128

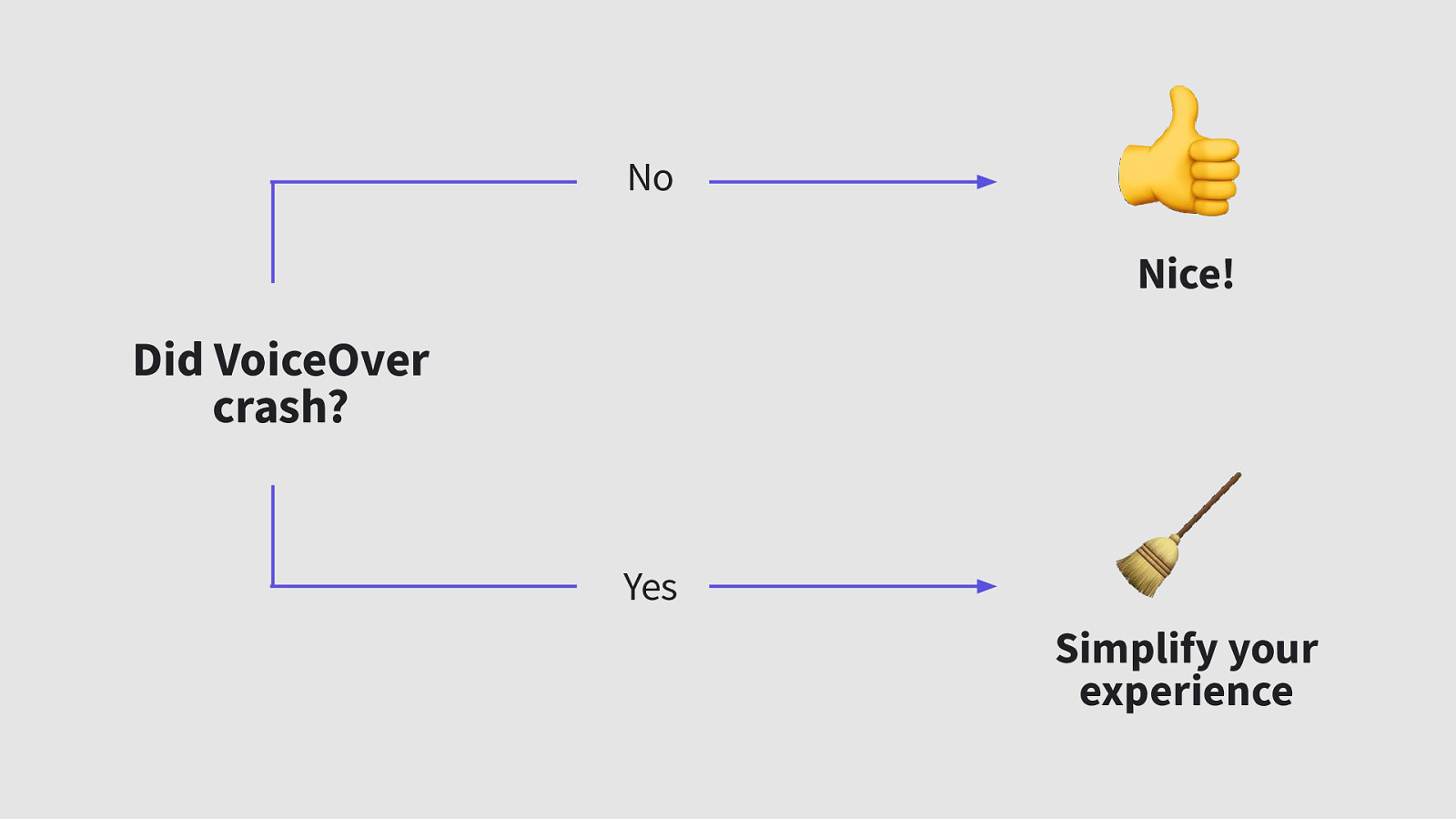

- Did VoiceOver crash?

- If no, awesome. Keep it up!

Slide 129

- If VoiceOver does crash, get to doing what you do best: advocating for, and submitting PRs to reduce your JS payload and DOM depths

- And don’t forget, you can press Command F5 again to turn VoiceOver off when you’re done

- It’s as simple as that

Slide 130

- Okay, whoa!

- The slide background color is yellow now!

Slide 131

- This is what we call a great segue

Slide 132

- I’m a designer by trade,

- Part of that job means coming up with alternate strategies for allowing people to accomplish their goals

- Because sometimes the most effective solution isn’t necessarily the most direct one

Slide 133

- With that in mind, we’re going to talk about another definition of performance:

- Which is the ability to actually accomplish something

- All of these little surgical tweaks and optimizations don’t mean squat if people don’t understand how to operate the really fast thing you give them

Slide 134

- To that point, another aspect of dynamically injecting a ton of radio inputs into a page is that it adds more things for a person to carry in their head

- This is called cognitive load, and it’s a huge problem

- It affects our ability to accomplish tasks, and importantly, our ability to accomplish tasks accurately

Slide 135

- Namely, cognitive load inhibits our memory

Slide 136

Slide 137

Slide 138

- Reading comprehension level

Slide 139

Slide 140

- And shockingly, our ability to visually process, and therefore understand what we see

Slide 141

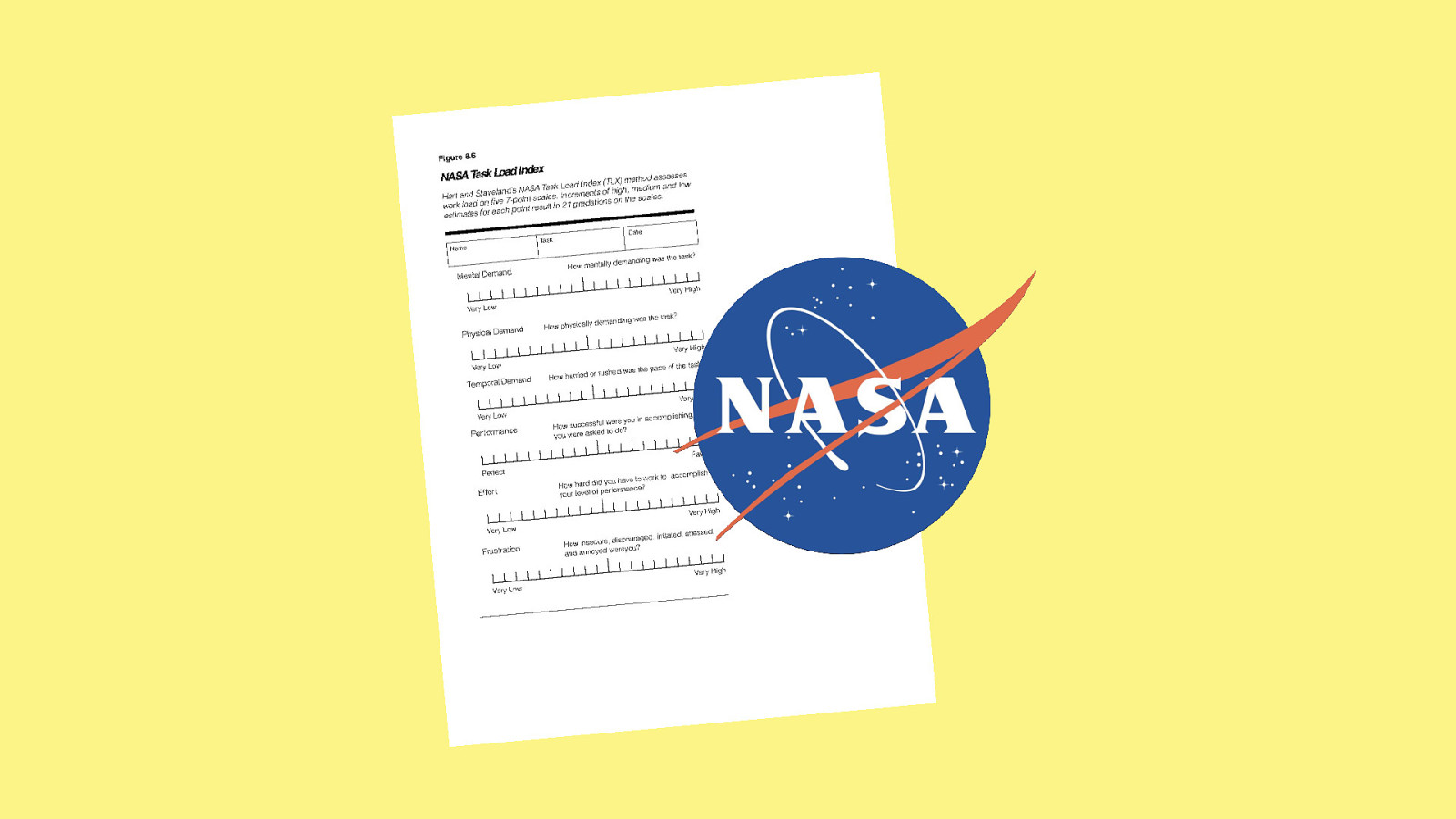

- Cognitive load is such a problem that NASA developed the Task Load Index, an assessment tool to help quantify it

- This isn’t warm fuzzy feelings about empathy, this is a serious attempt by a serious government agency to refine efficiencies and prevent errors

- One of the most interesting things about the existence of the Index is that it’s an indirect admission that disability can be conditional

- Think about it: when’s the last time you were using technology while tired, distracted, sick, or learning a new skill and the outcome isn’t what you desired?

- Heck, when’s the last time you were trying to use technology while drunk?

- Cognitive load an important thing to track for building rockets, sure

- But it also translates to other complicated things like making and using software

Slide 142

- One of the things we can do to lessen cognitive load in software is to lessen the amount of information someone has to parse at any given moment

Slide 143

- For the medical education app, we could have added an additional step into the user flow that asks a high-level segmenting question

- It’s a little more friction, sure

- But it’s being used strategically as a focused choice, to keep the overall cognitive load lower for the subsequent parts of the user flow

Slide 144

- This would help to filter down the results you get

- Which makes it easier for both the user and the browser to parse

Slide 145

- The other big-picture question we need to ask is if all this work is even necessary?

- The most performant page is the one you never have to use

- By which I mean how often can we side-step these issues by using other resources and information previously made available to us by the user?

Slide 146

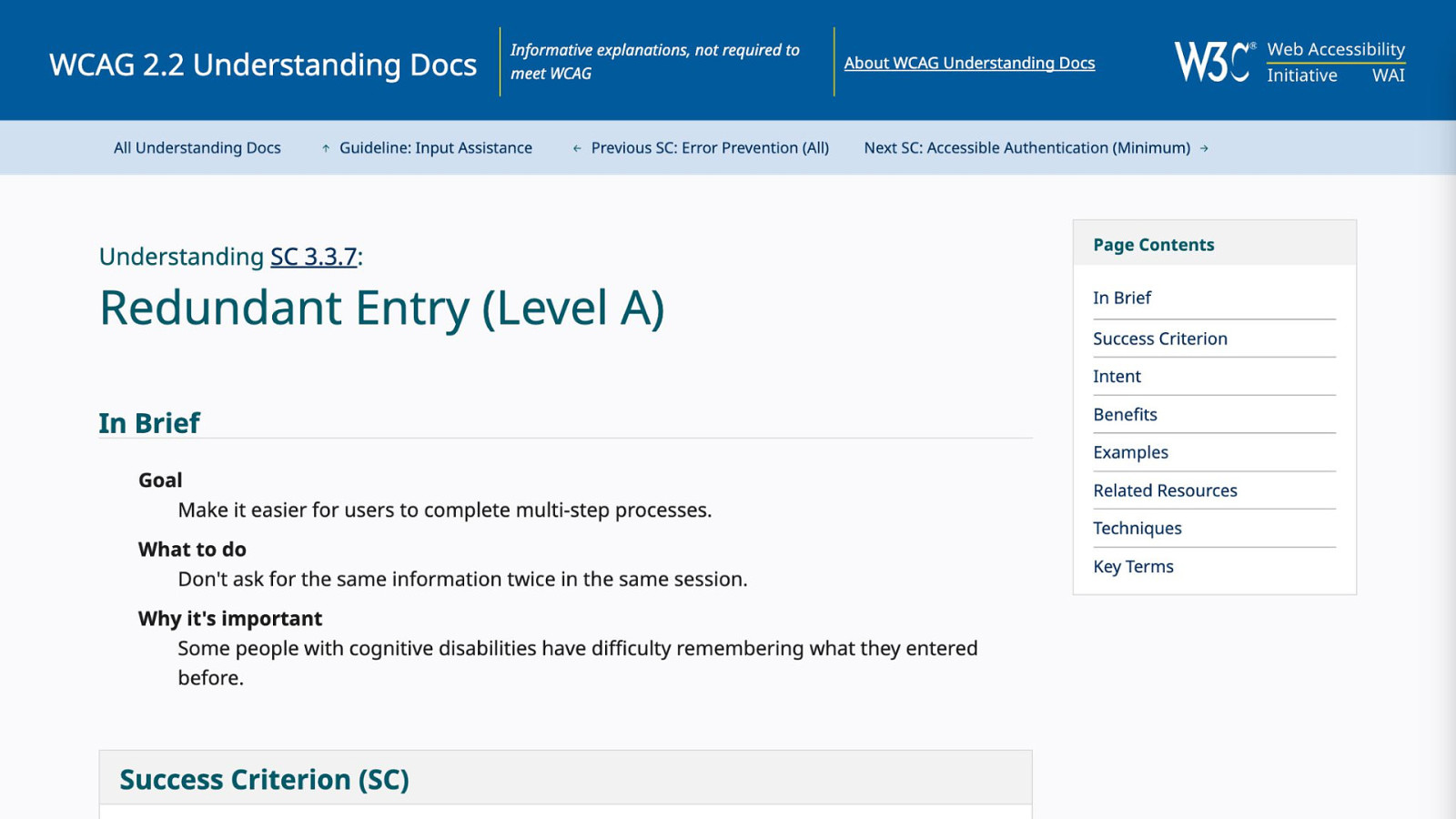

- This is such an important thing that the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines has a rule for it

- Success Criterion 3.3.7 Redundant Entry is level A, meaning it is a baseline requirement for all content on the web

- It stipulates that you as the provider of the experience do not require someone to enter information that they have previously successfully submitted earlier on in the experience

- Not only is this good UX, but it’s also helpful for people with cognitive and motor control disabilities

- Like, observing this rule could quite literally save someone from experiencing pain from unnecessarily filling out information they already submitted

- So, be sure to remember to keep this in mind the next time your company’s shoddy reimbursement system makes you fill out the same info in triplicate before submitting

Slide 147

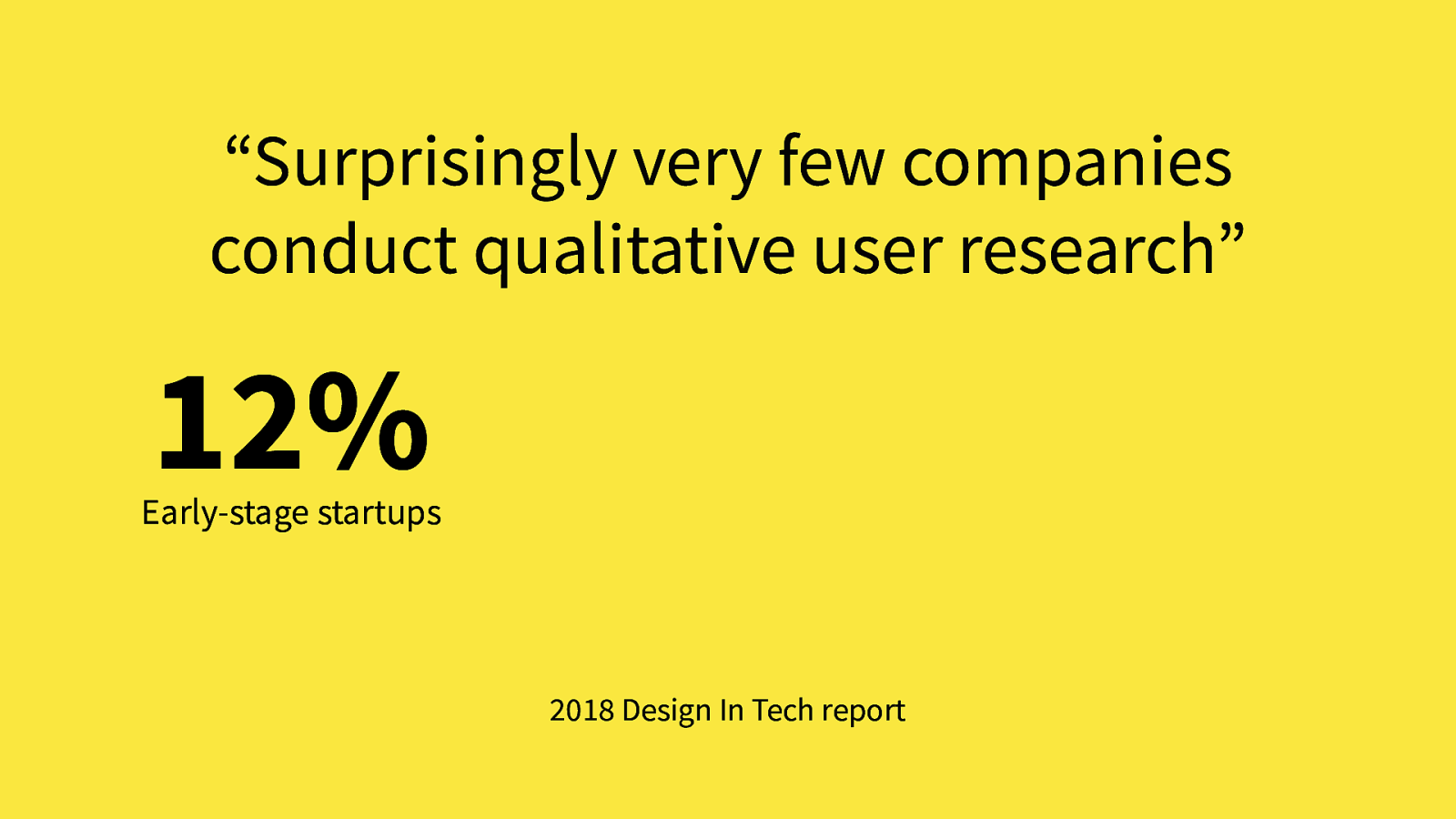

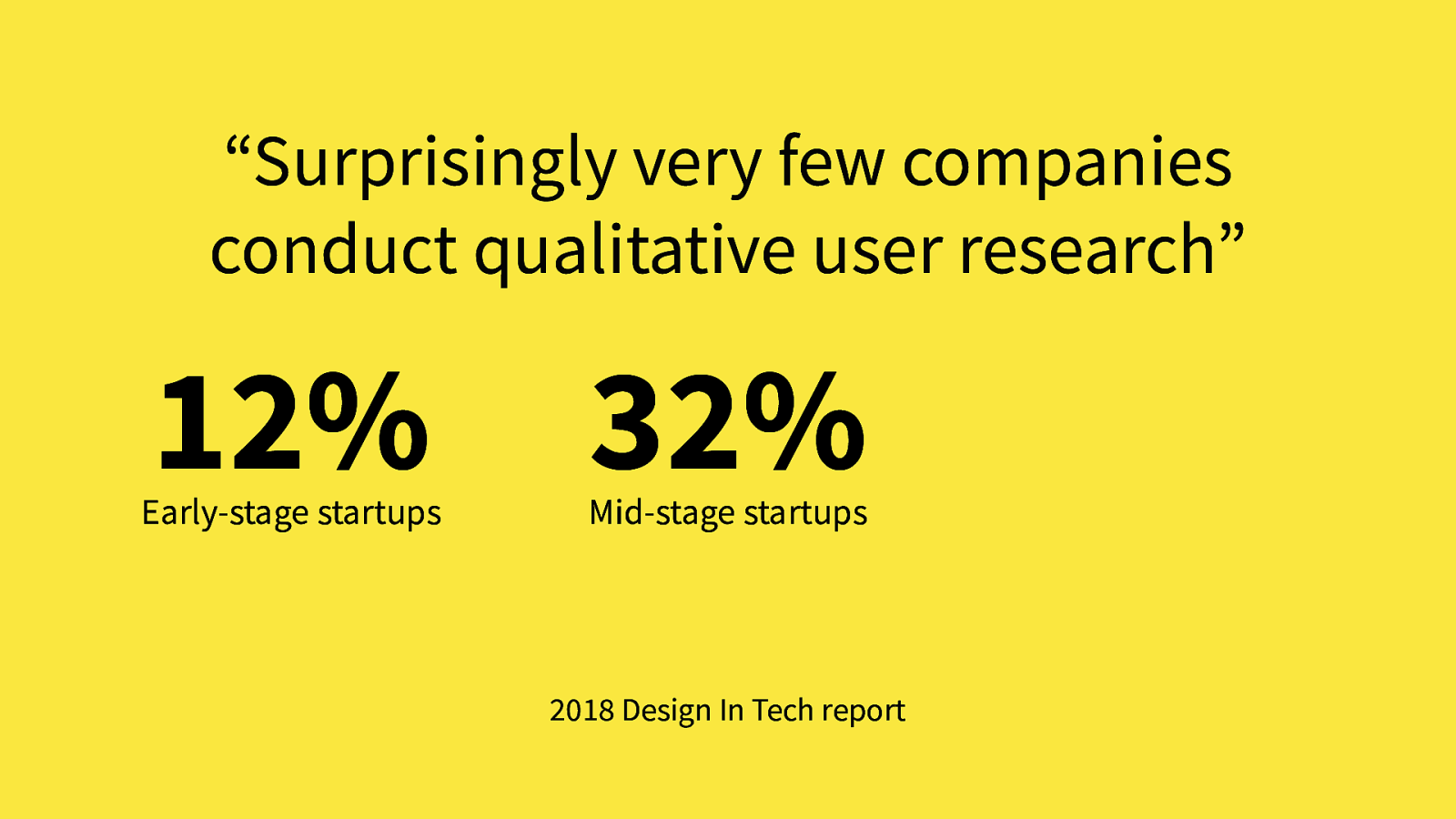

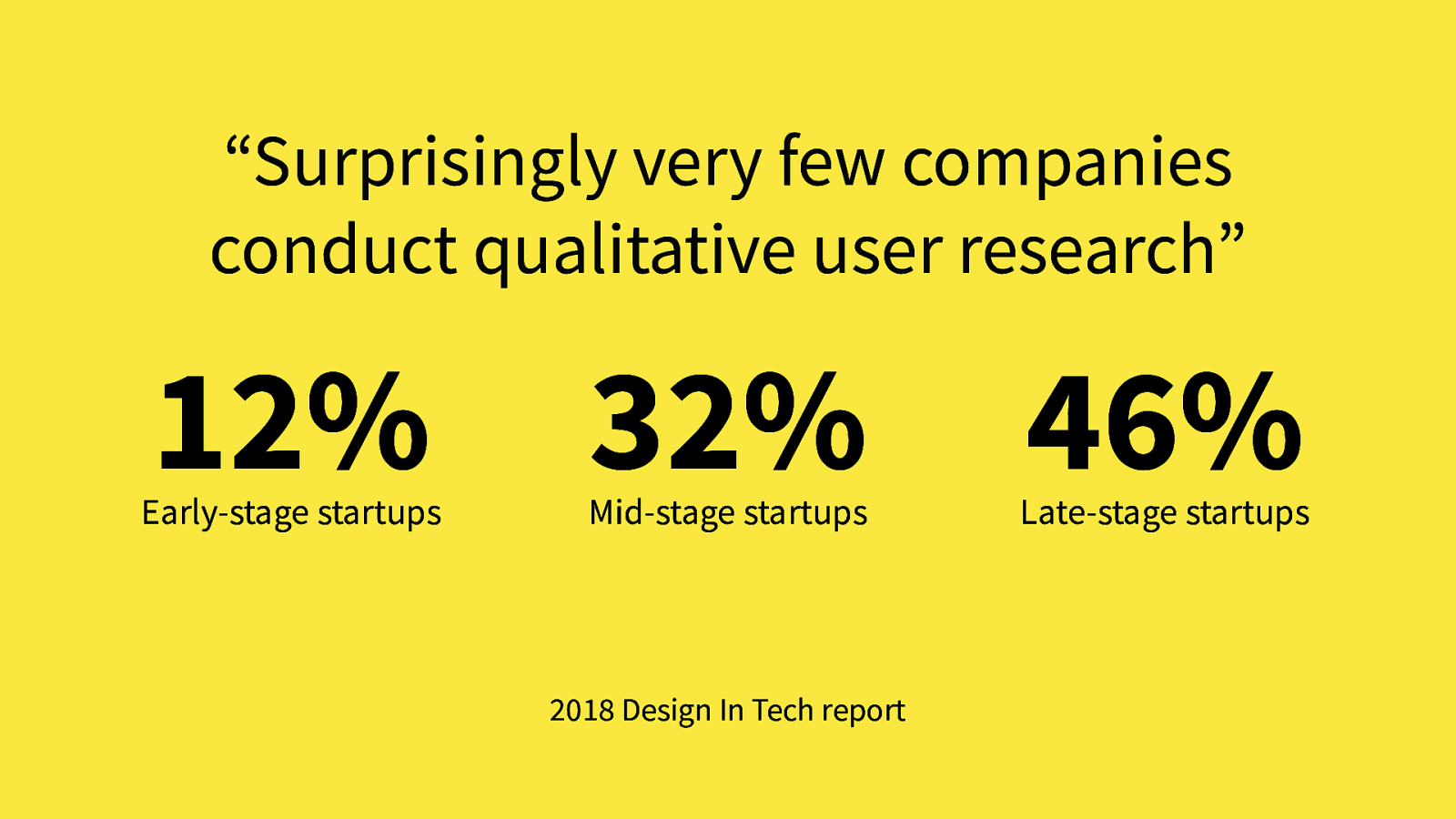

- If you’re interested in this sort of thing, the 2018 Design in Tech report is a must-read piece

- One of the surprising things it revealed was that very few companies conduct qualitative user research

- Which is the practice of asking people how they’d use a feature, and how they feel while they do it

Slide 148

- So, 12% of early-stage startups

Slide 149

- 32% of mid-stage startups

Slide 150

- And 46% of late-stage startups don’t do qualitative user testing

- That’s sub-50% for each category of startup listed. Yikes.

- I’m not a numbers person, but there does seem to be a trend going on here, and it’s not a great one

- Another interesting thing is barely any companies conduct qualitative testing for features after launching them, even if they do perform qualitative testing beforehand

- So we’re all just collectively throwing features, and the piles of code that these features require into the larger, ever-evolving ecosystems that are our products, and then not checking to see how they’ll actually affect things.

Slide 151

- We also need to remember that we’re only seeing those companies that beat the odds

- The market is built on top of the corpses of failed businesses who poured all their cash and resources into the wrong strategies and features

- When we parrot these perceived successes at our own places of work, know that these successes are largely coming from sheer probabilistic luck

Slide 152

- If you need a more concrete example of this, consider Evernote

- An app that started as an industry darling is now mainly talked about in terms of concern for what will happen to note content when the company inevitably folds

- This stems from decades of mismanaged strategy, redesigns that didn’t meet the mark, and features that failed to find product/market fit

- We should all strive to do the opposite here:

Slide 153

Slide 154

Slide 155

Slide 156

- Make its value apparent, and then

Slide 157

- Ask people what they think of it, and continue to ask them what they think of it as time goes on

Slide 158

- So, in wrapping up this talk I have three requests:

Slide 159

- First, let’s break down all these isolated islands of siloed practice.

- It’s a dirty little secret that the bulk of accessibility issues are created in the design phase. I’d wager the same is true for performance

- As performance-minded engineers we can collaborate earlier with designers and plead our cases in a way that they’ll actually be willing to respond to

- One such way is to proactively identify potential bottlenecks where a redesigned user flow can cut the Gordian knot.

- Remember: at its heart performance is user experience, and sometimes the most impact happens before the development layer

the isle (Pun intentional)

Slide 160

- The second ask is me carrying the torch from a talk from an earlier iteration of this conference

- There’s a four year old issue on GitHub from Scott Jehl asking about taking the spirit of what this talk drives at and incorporating it into Lighthouse

- We all know that Lighthouse is an incredibly influential tool

- I’d also like to point out that there are a ton of incredibly smart, influential, and dare I say friendly-looking people here today

- And a little renewed attention on this issue could do a lot of good.

Slide 161

- The third big ask is acknowledging that it’s one thing to read about something and believe it to be true,

- But it’s another thing entirely to put it out into the world without verifying it works

- Shoutout to Tammy’s wonderful morning keynote here, where she encourages us to get comfortable with being uncomfortable

- So, in the spirit of that, why not experiment with incorporating basic assistive technology checks into your performance audits?

Slide 162

- The web, and more importantly, the people who use it, are too vital not to.

Slide 163

- Thank you for your time and attention, and thank you to performance.now() and it’s organizers and staff for this opportunity

- My contact information is available on my website, which is ericwbailey.website

- And I’m also on Blueky and Mastodon these days

- I am also terminally online, so please feel free to reach out anytime, and thank you again!