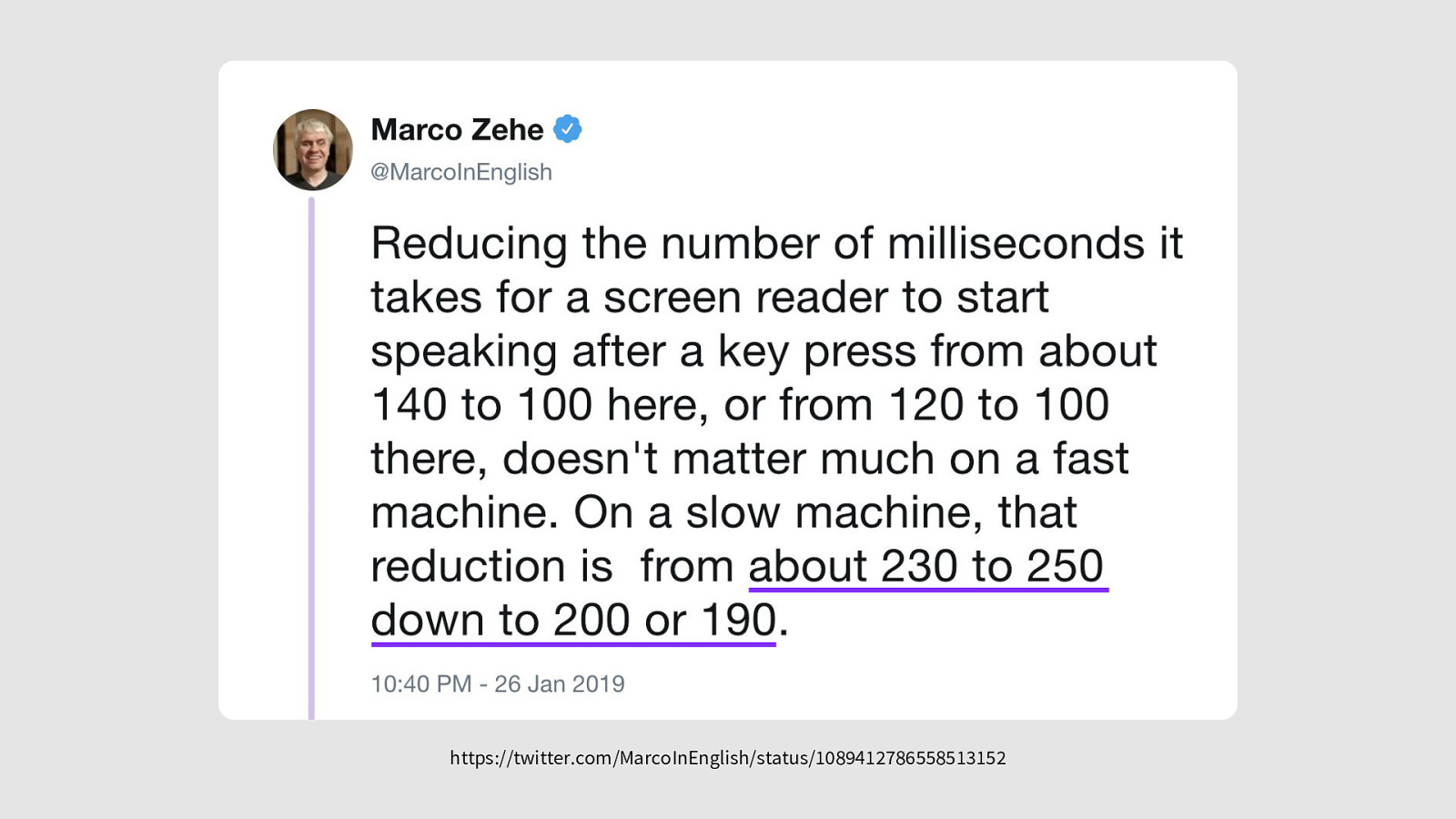

- The intersection of Performance & Accessibility, #PerfMatters 2019

A presentation at #PerfMatters in April 2019 in Redwood City, CA, USA by Eric Bailey

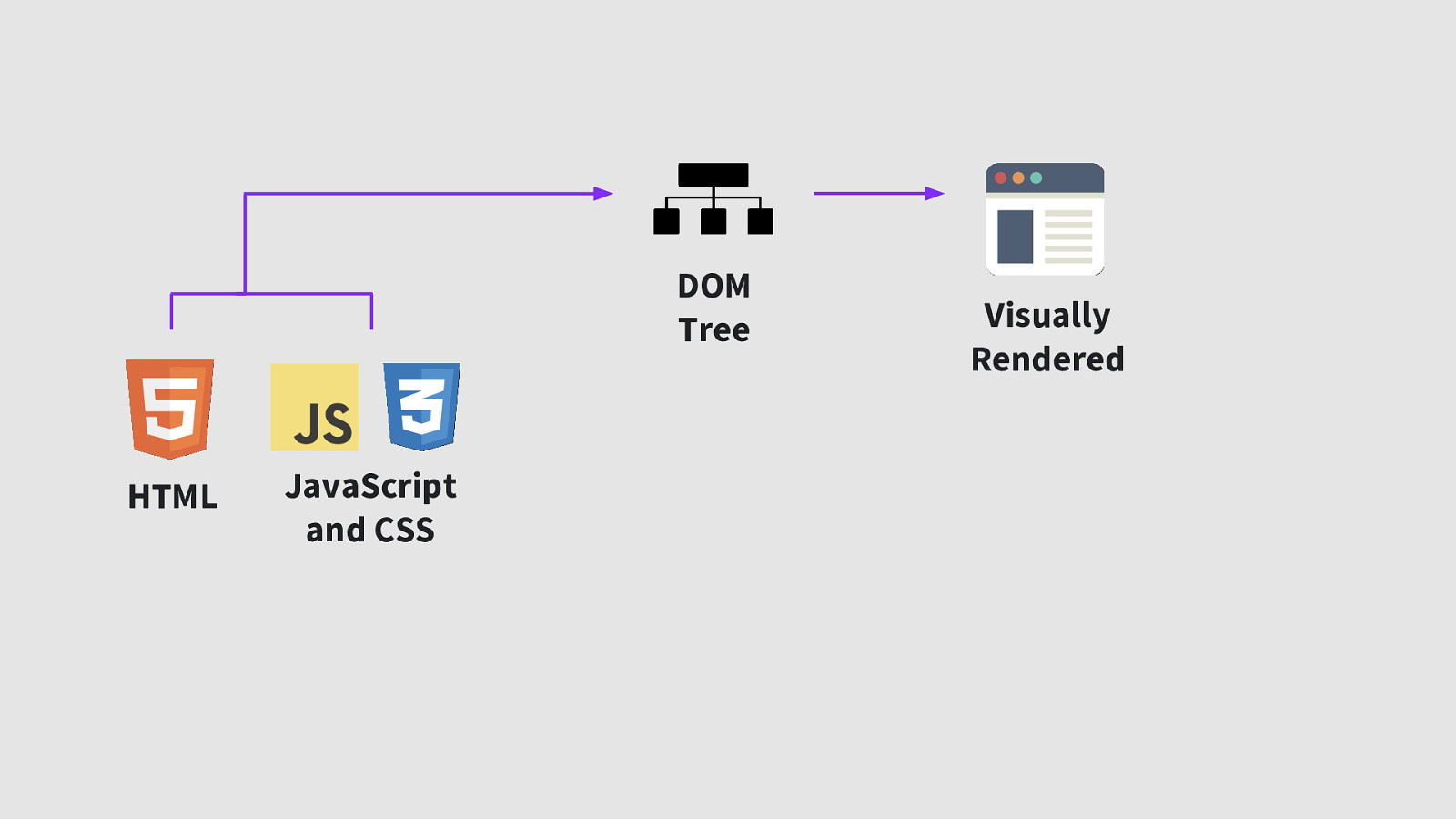

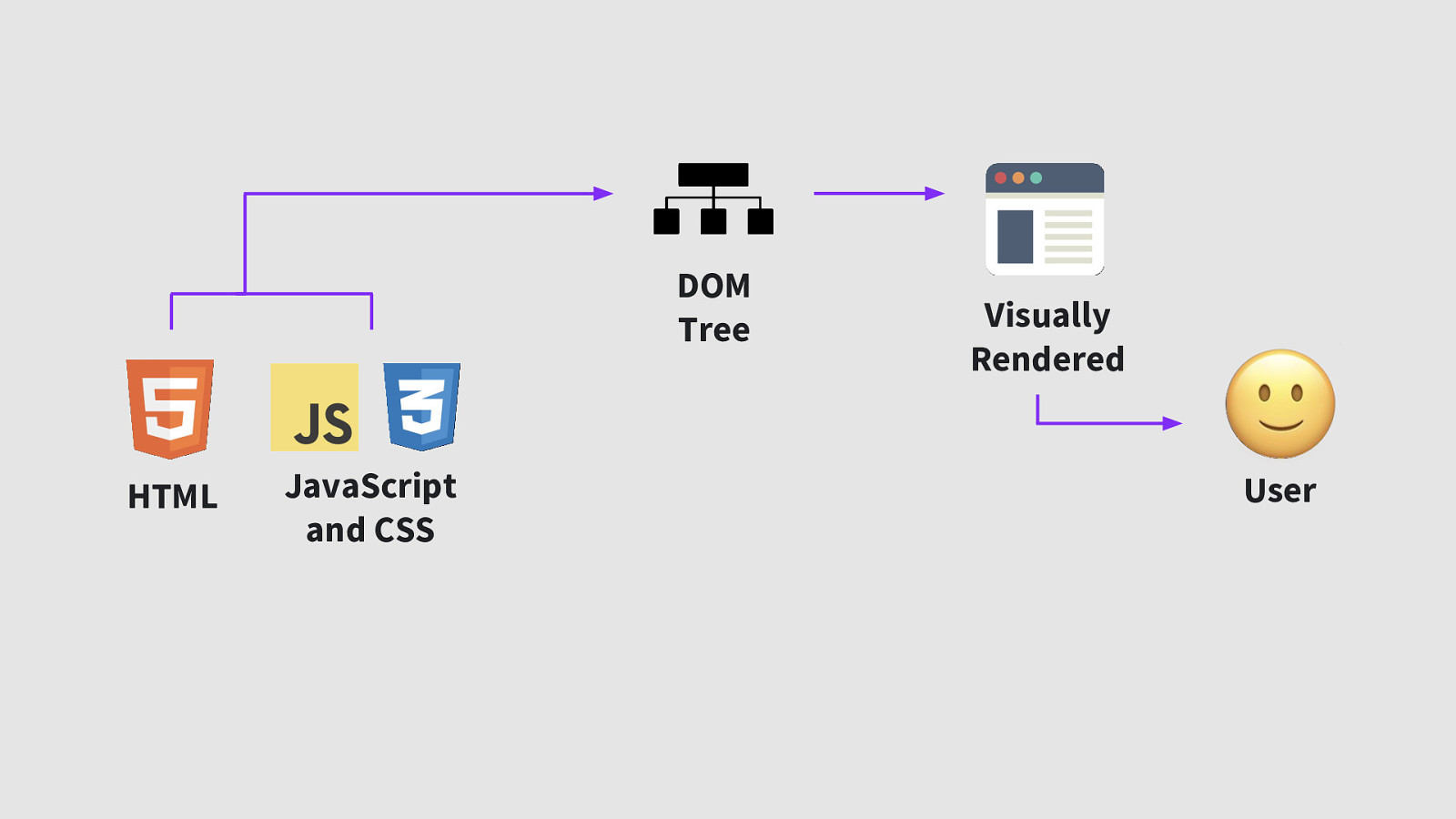

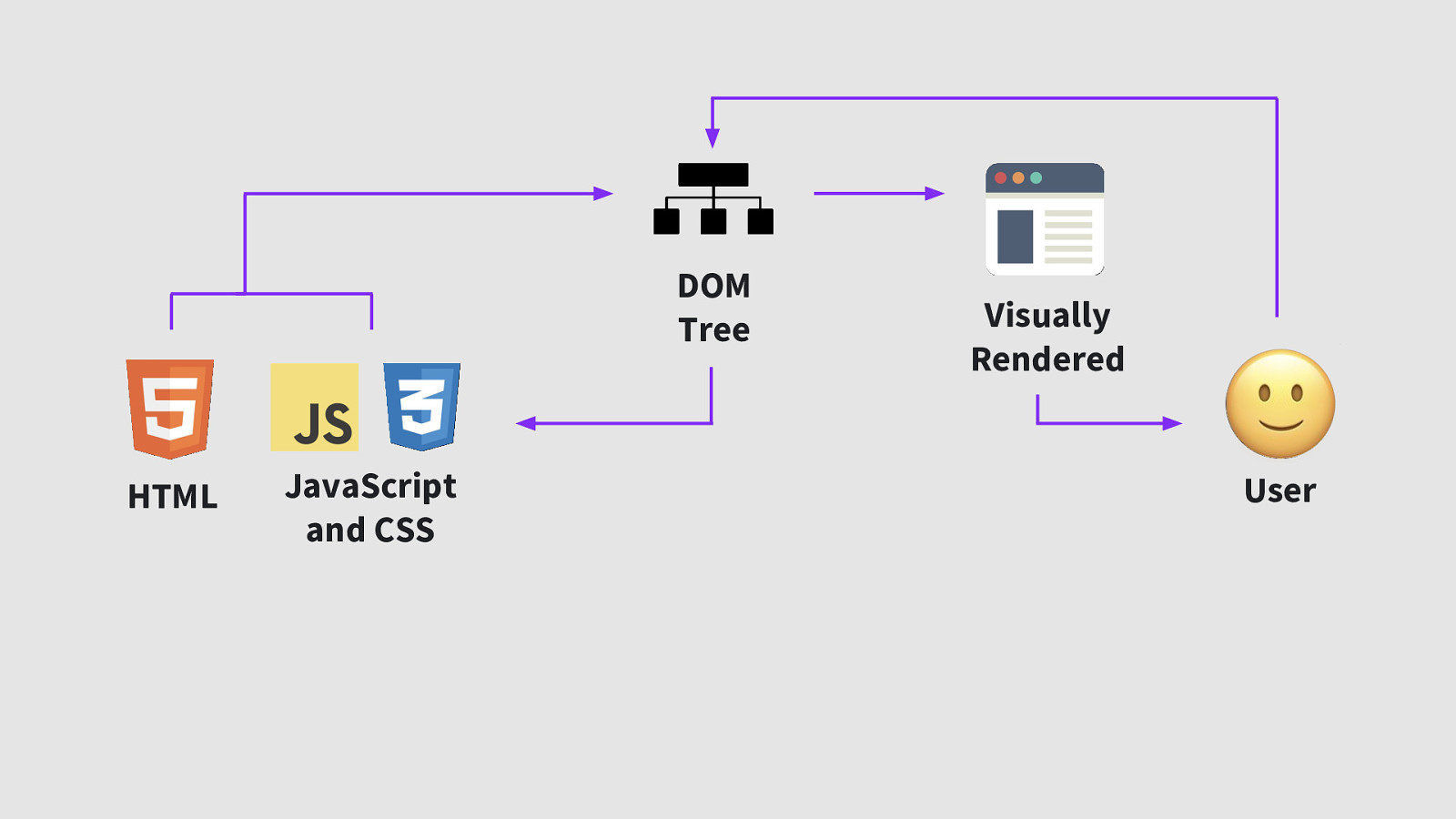

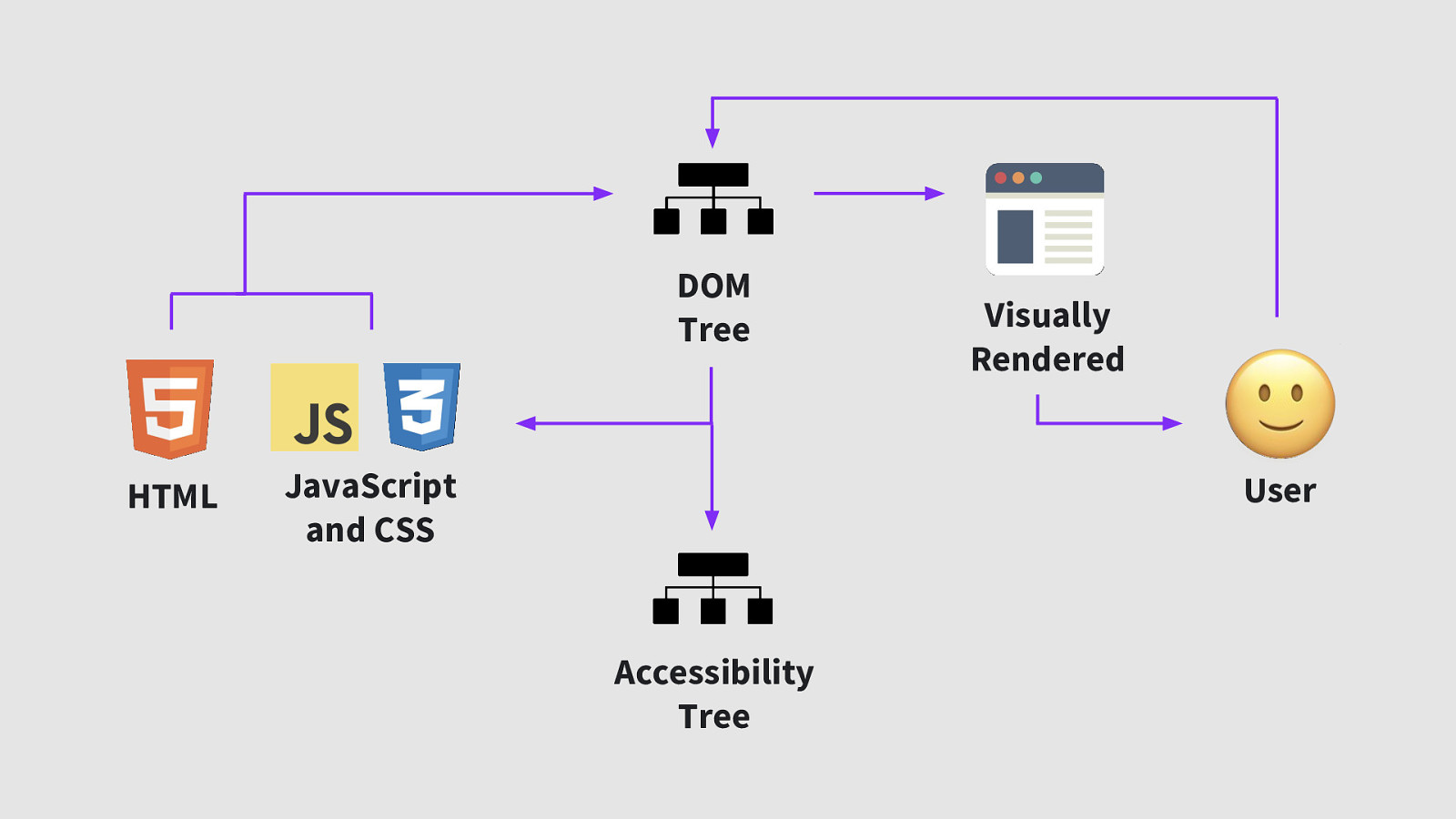

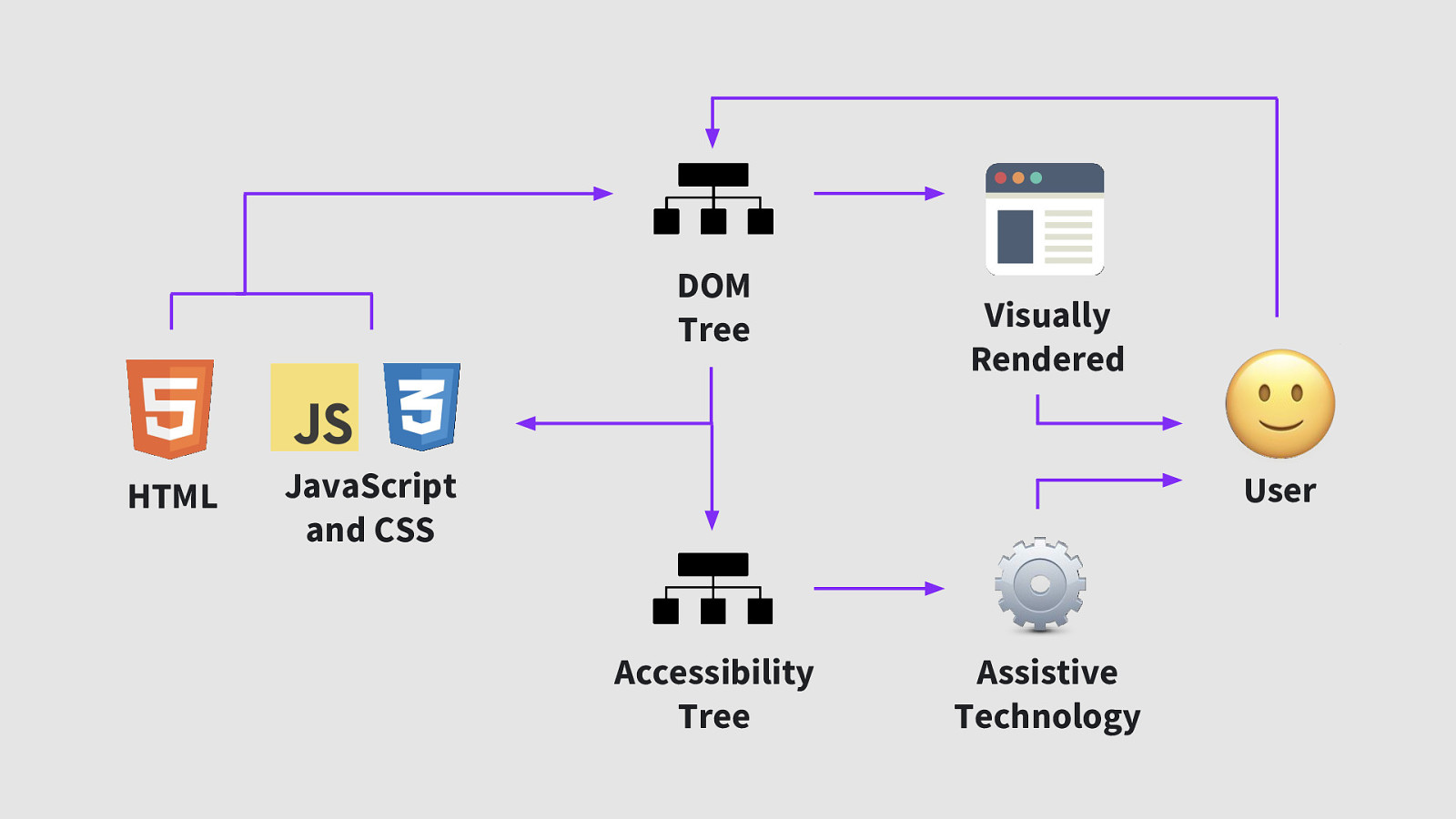

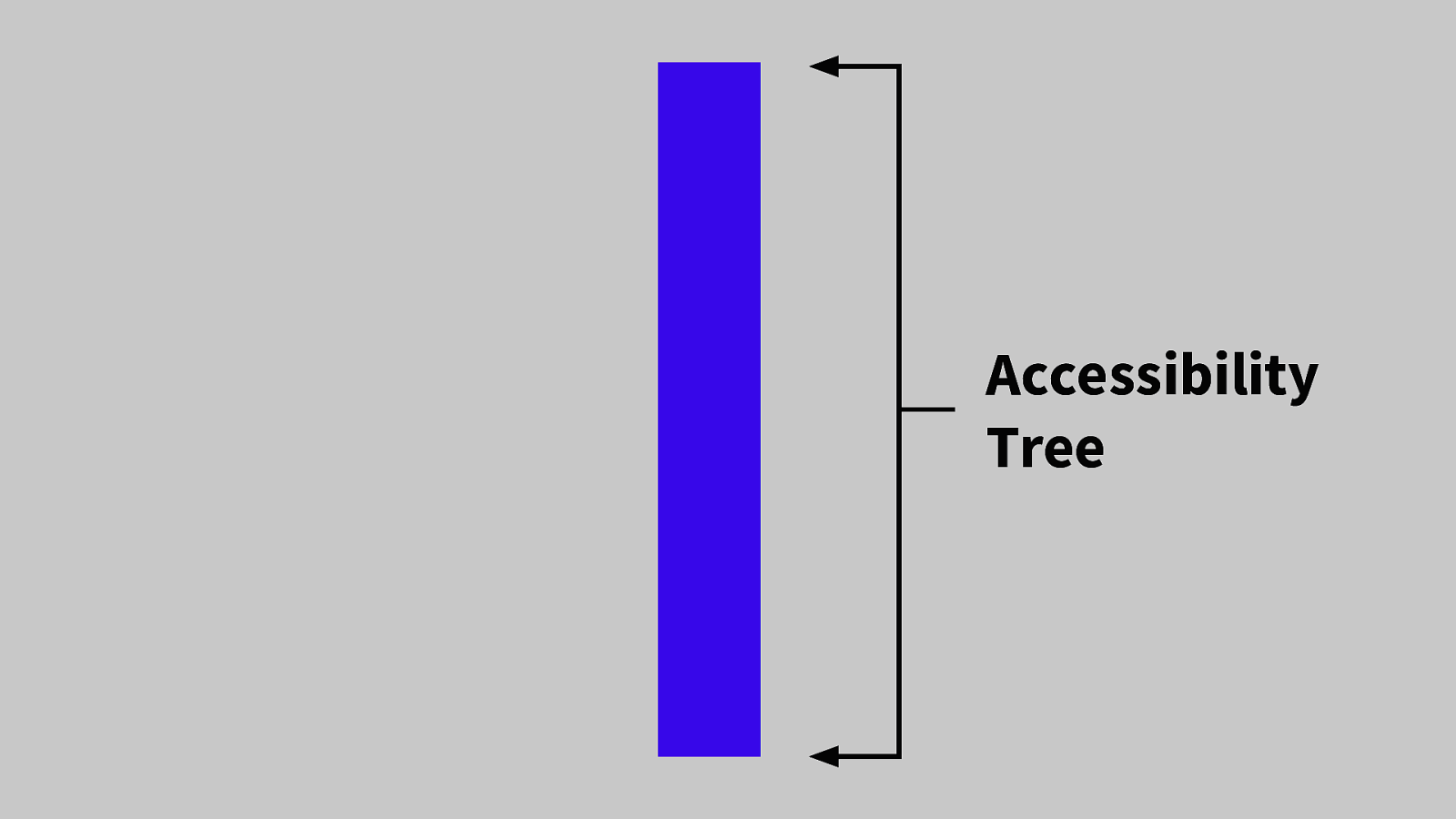

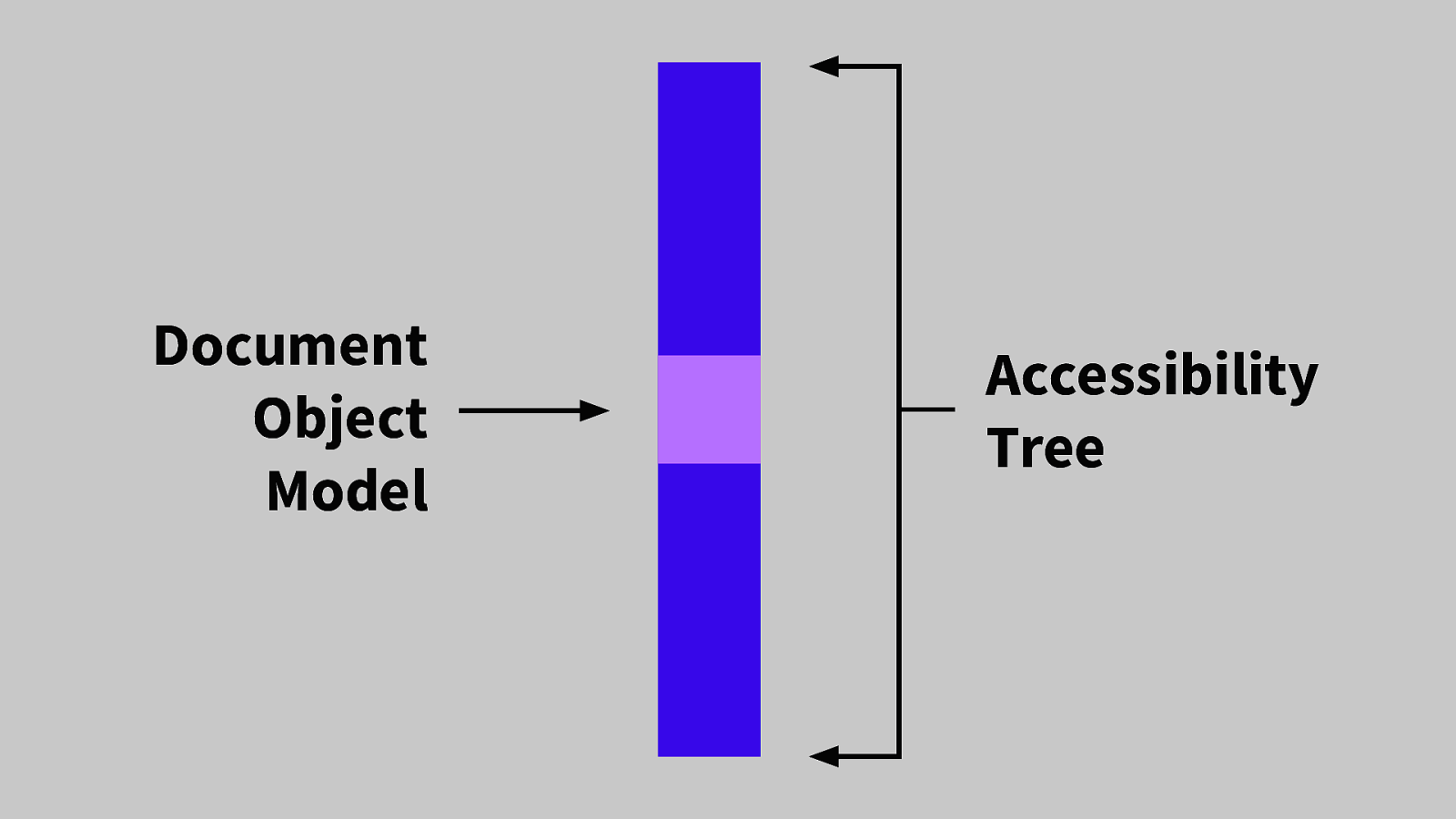

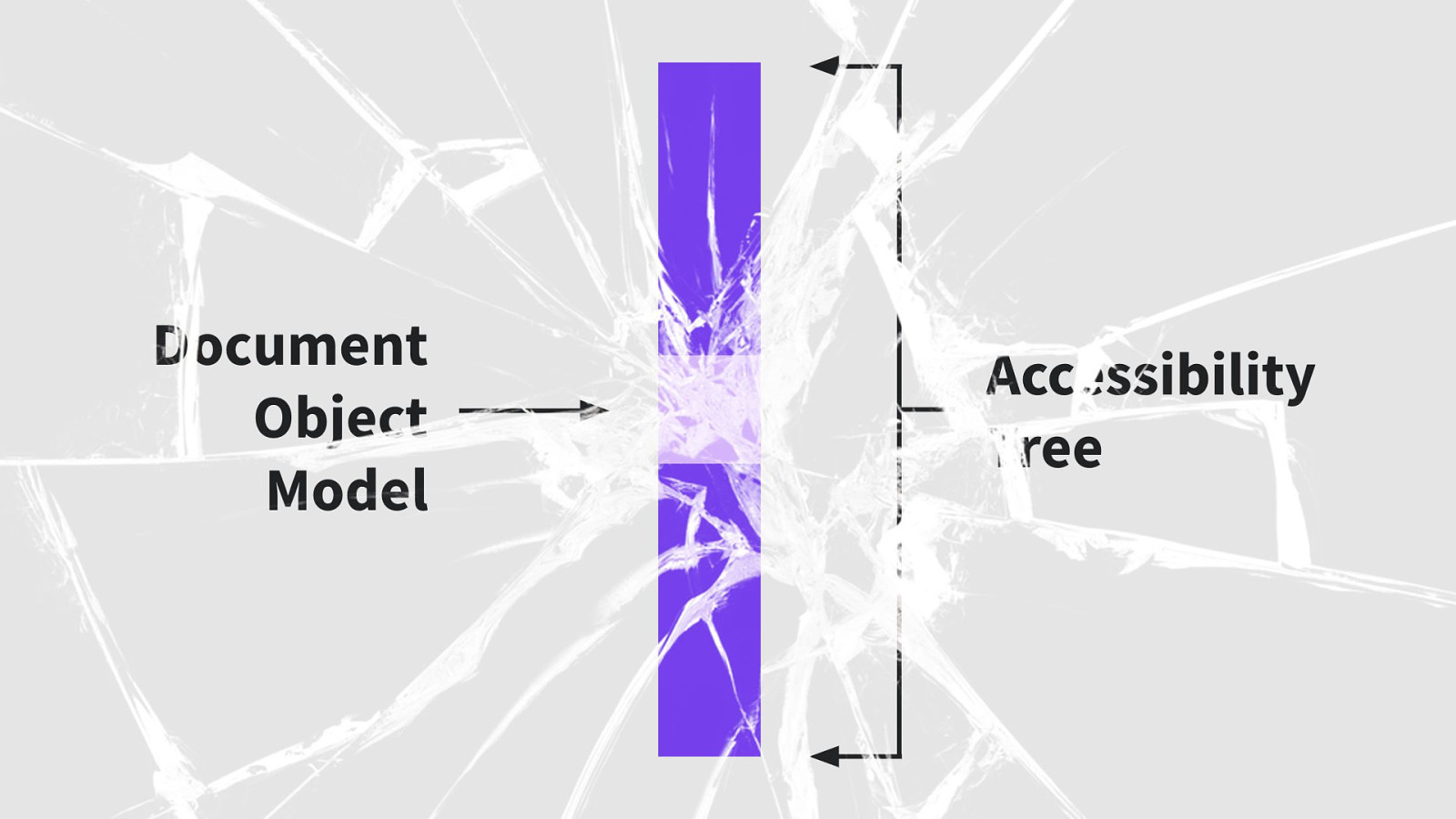

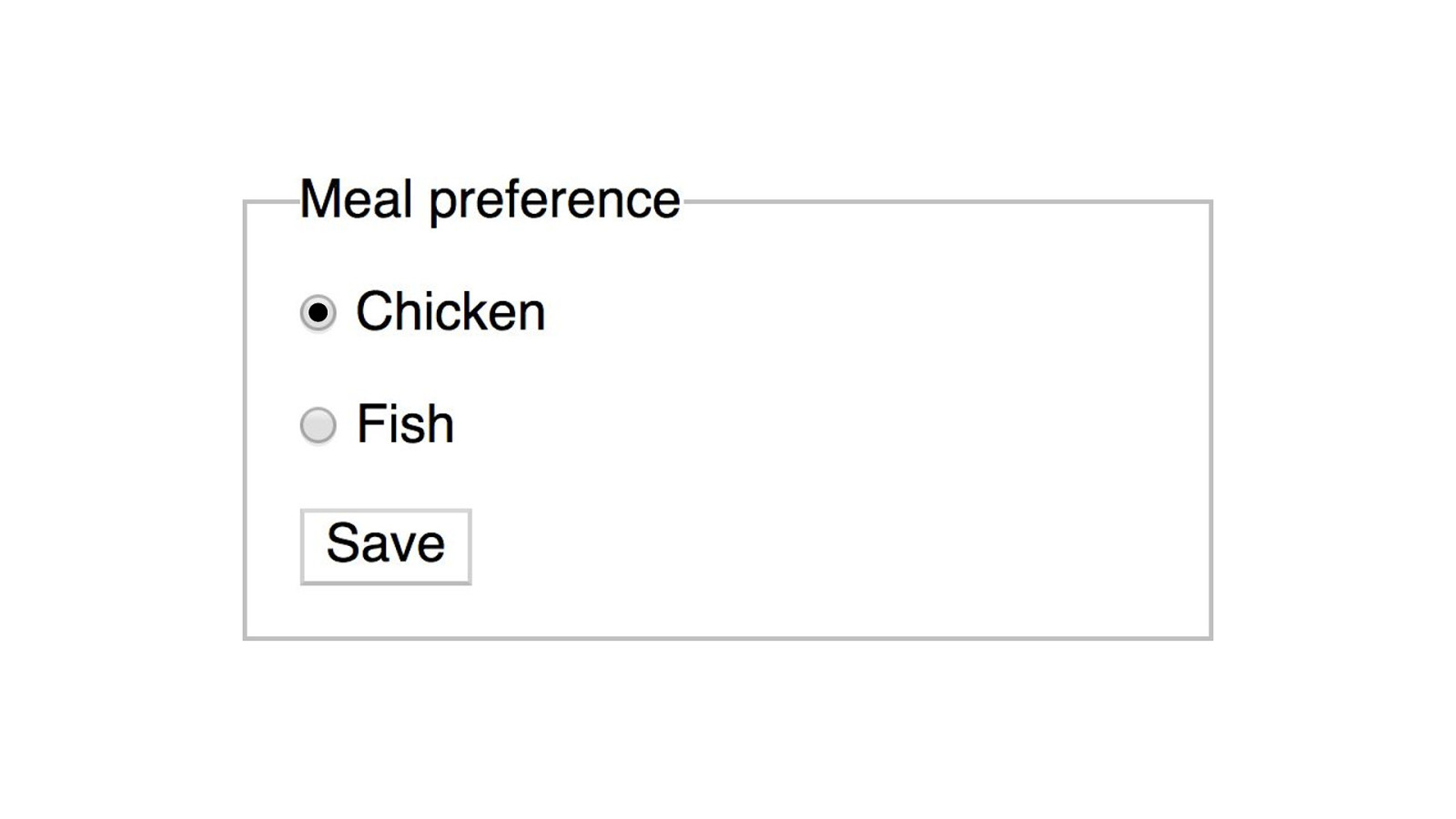

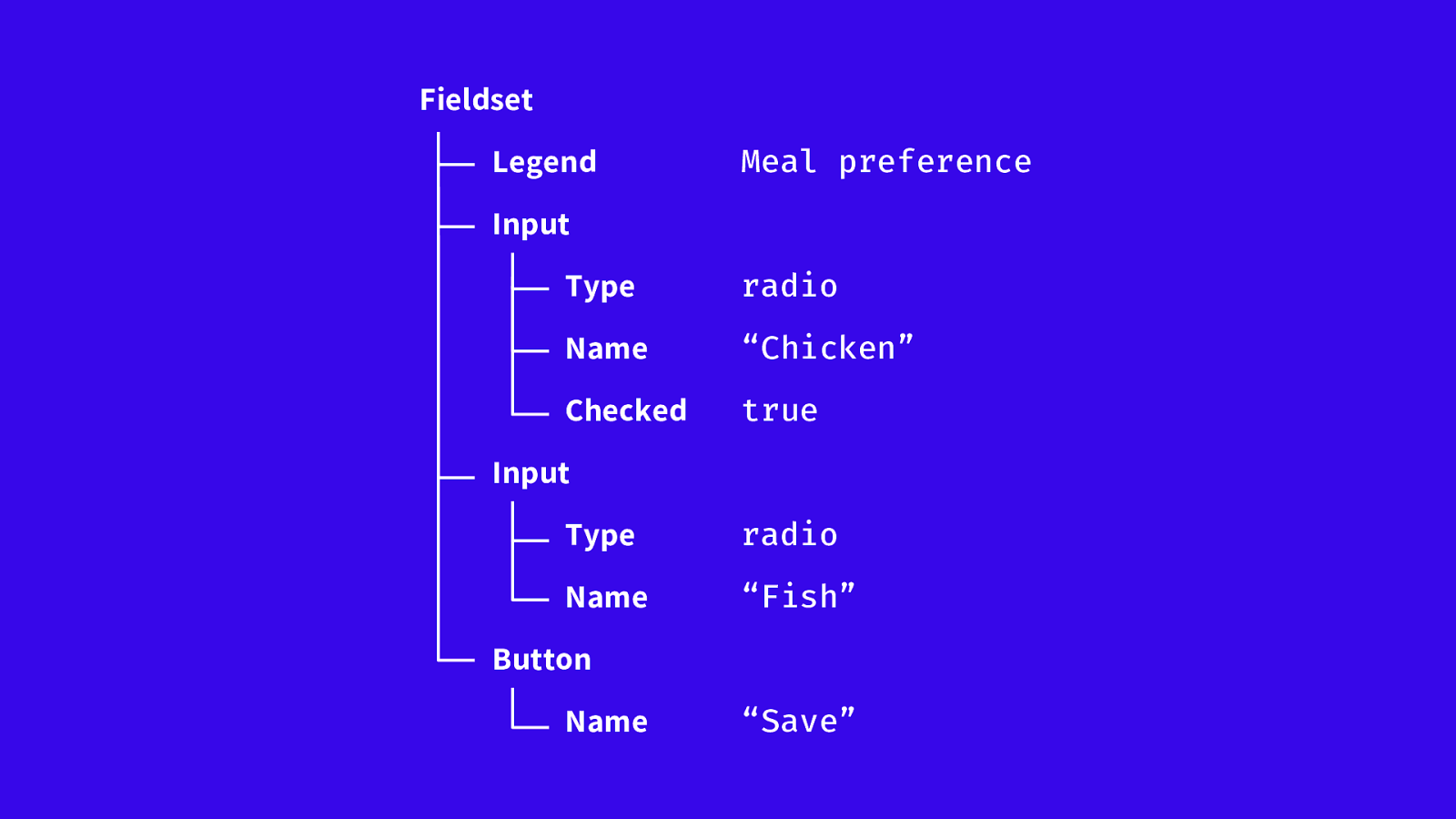

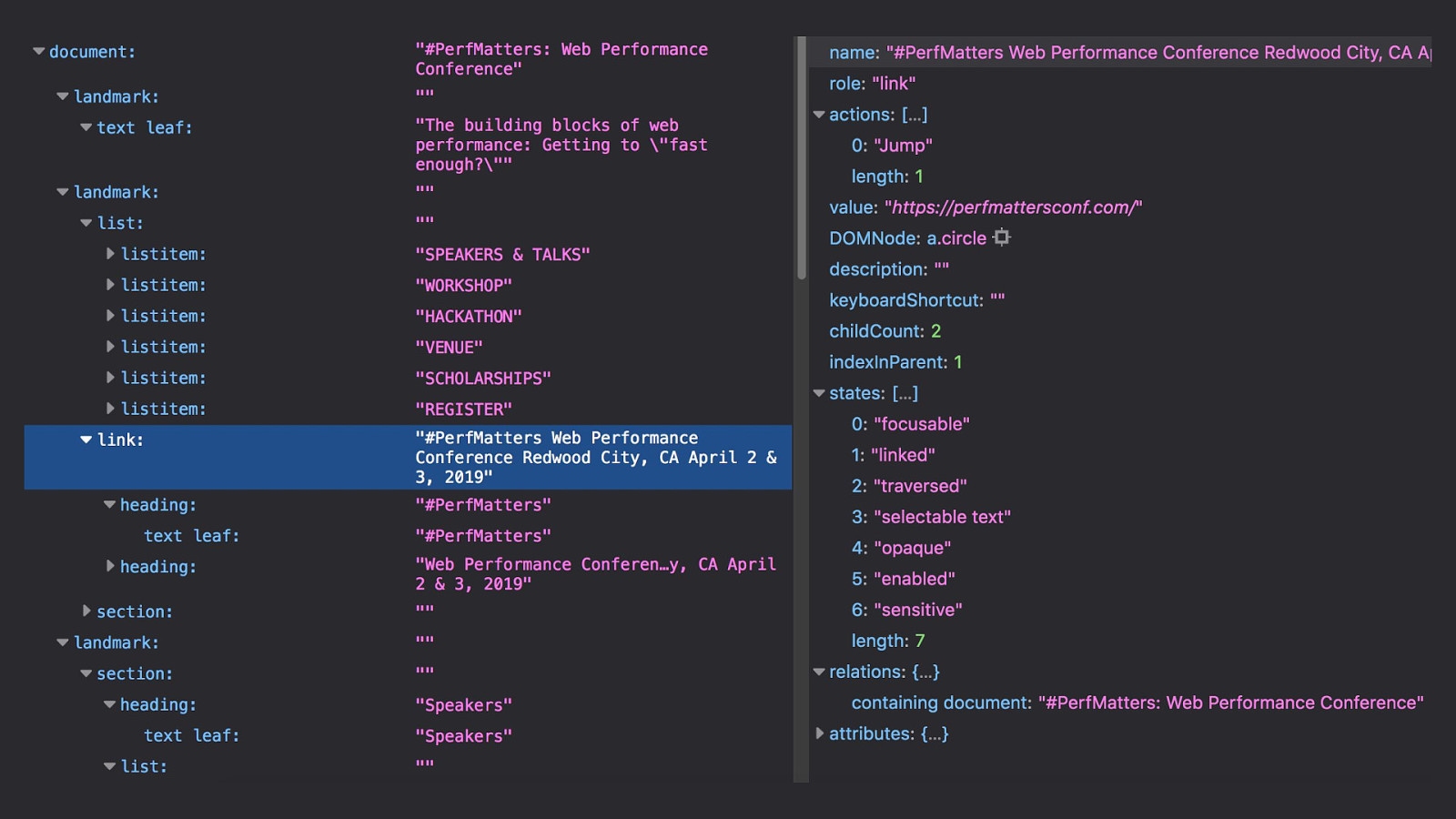

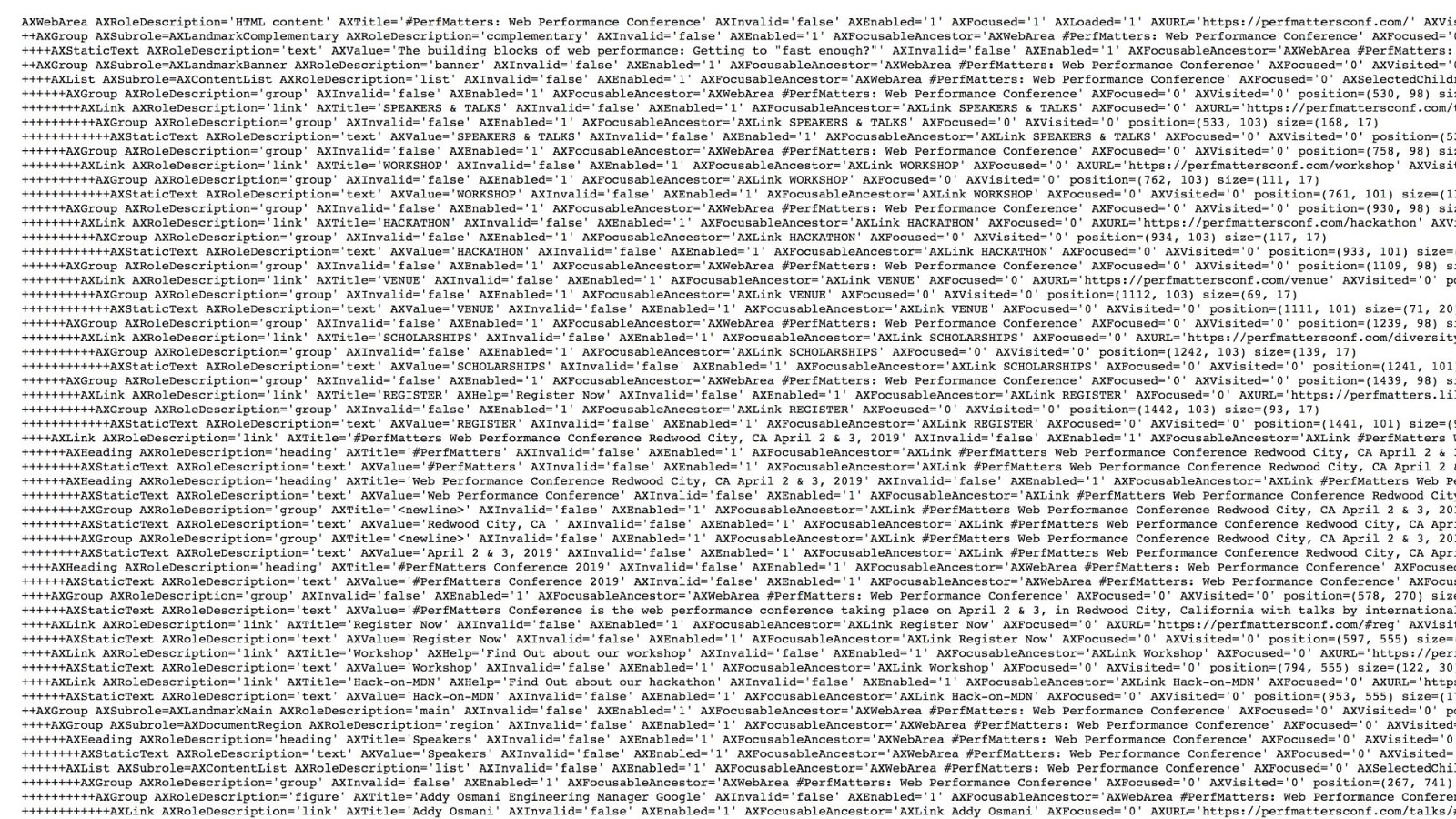

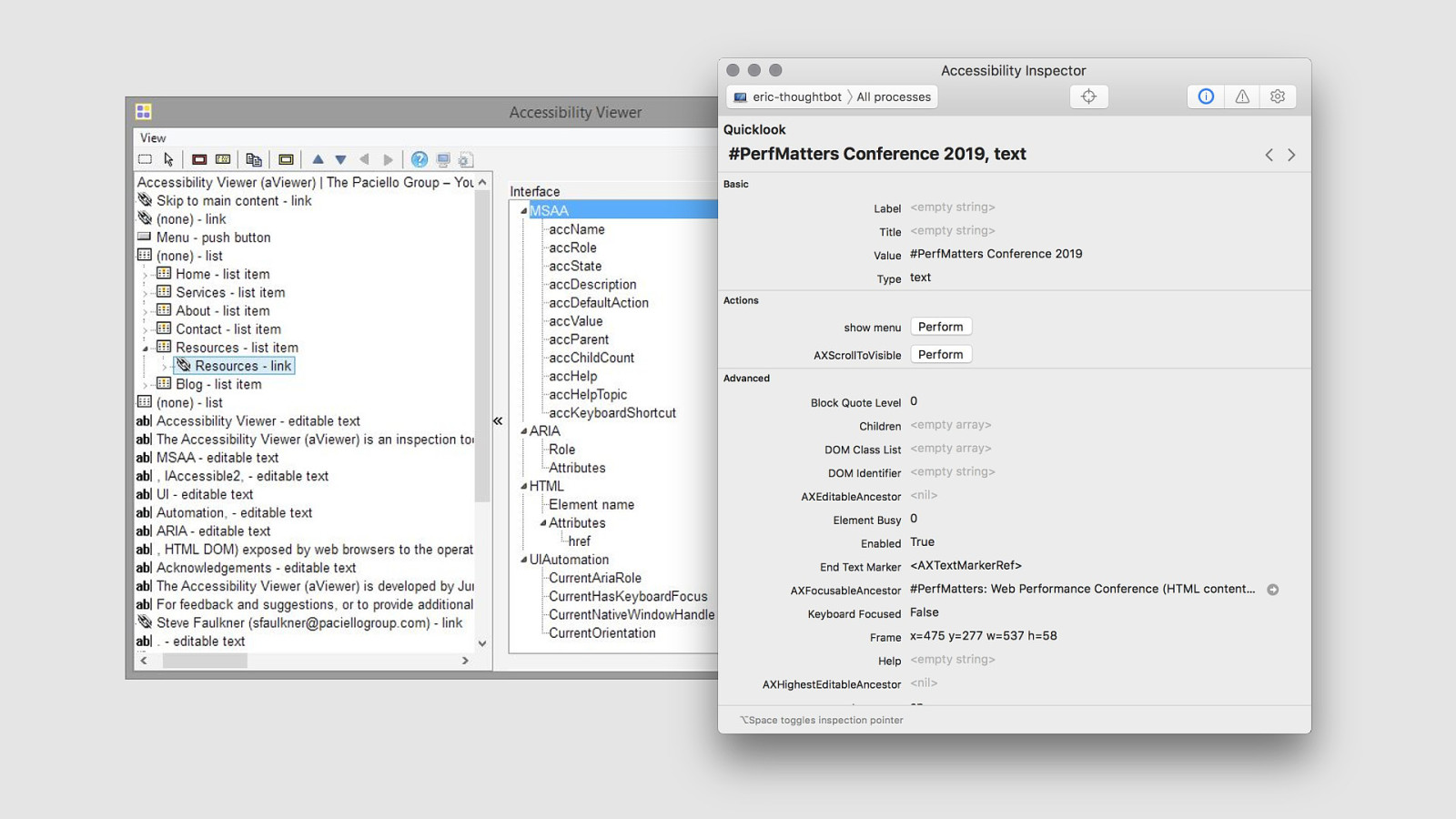

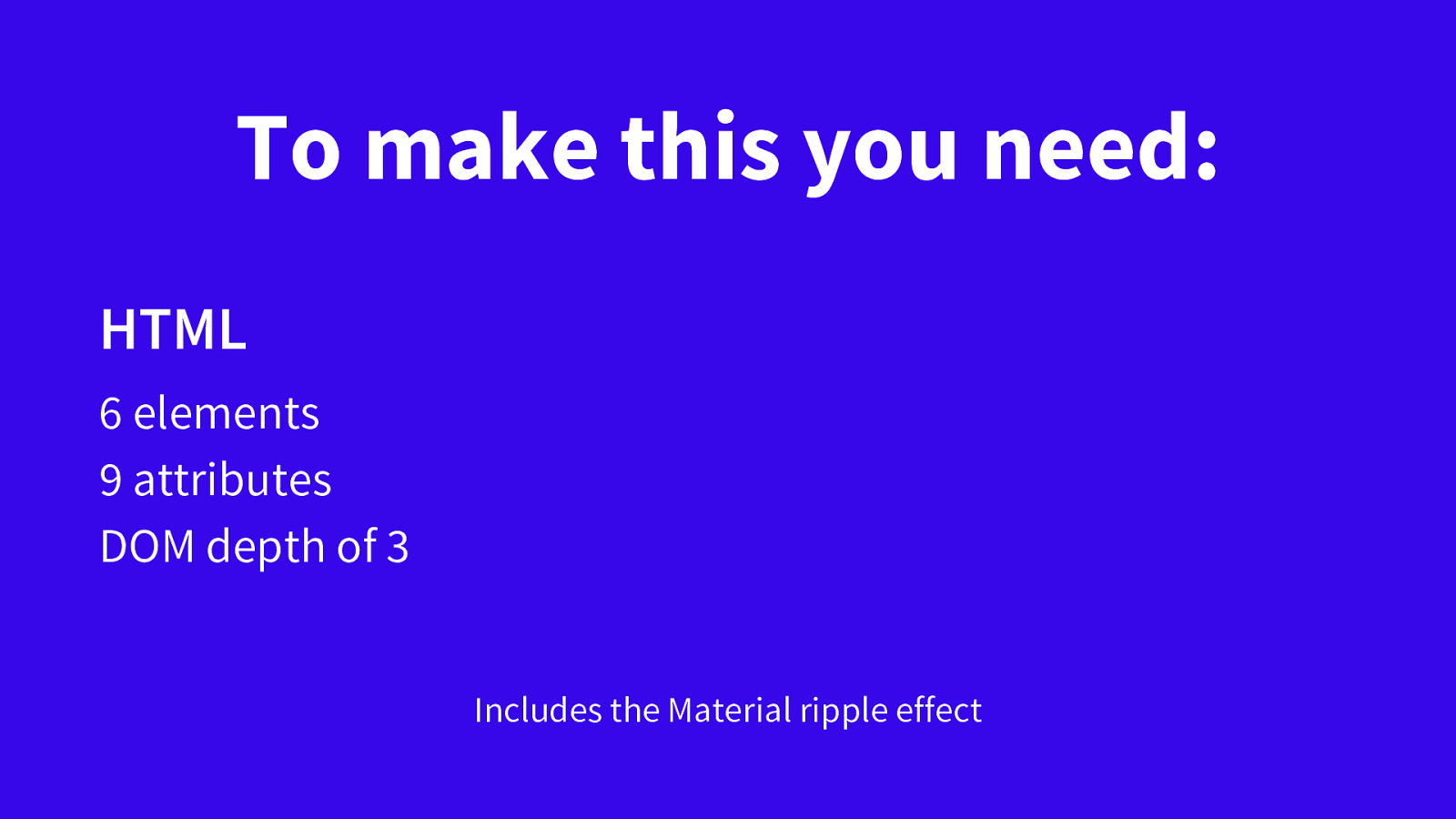

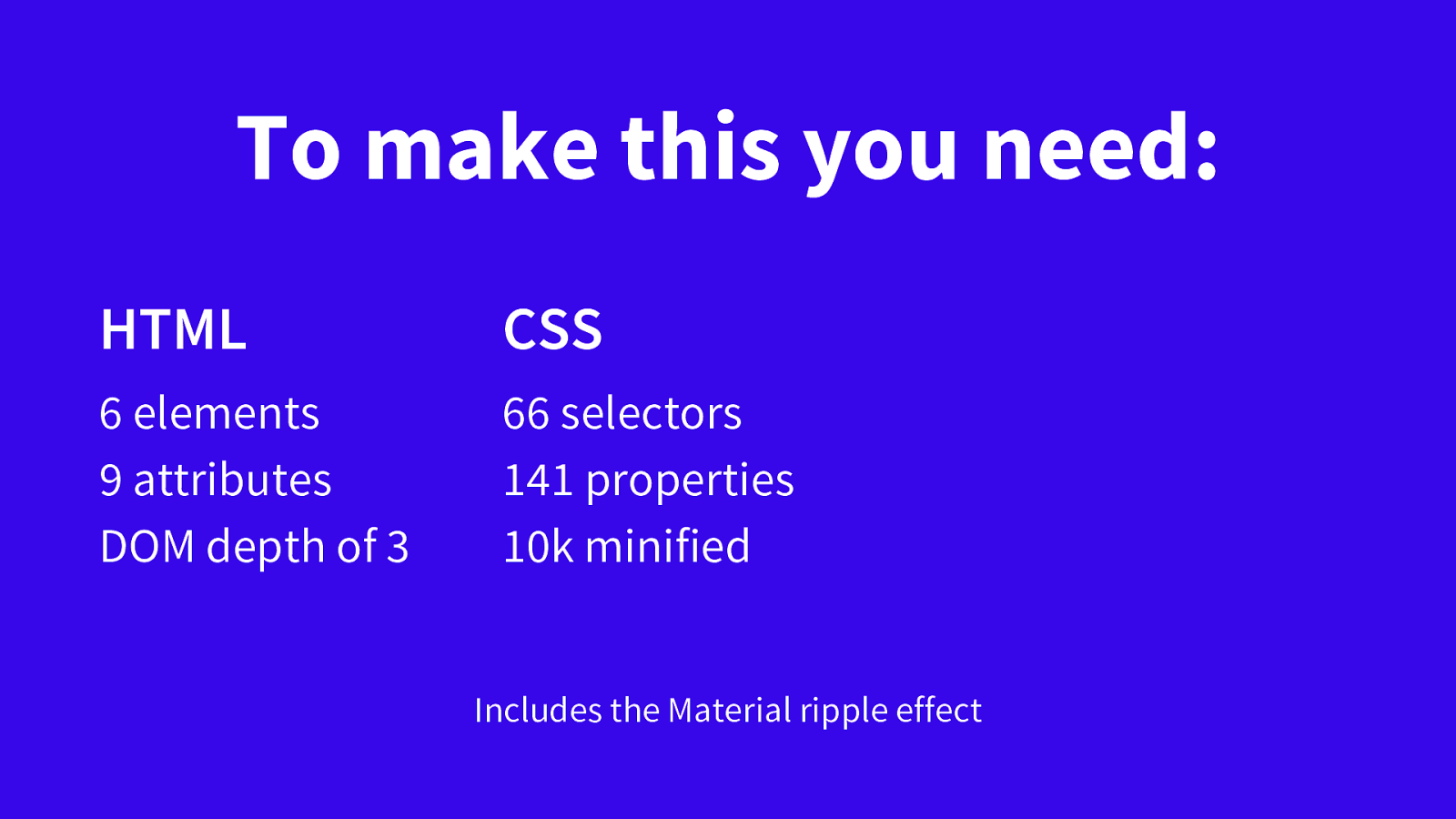

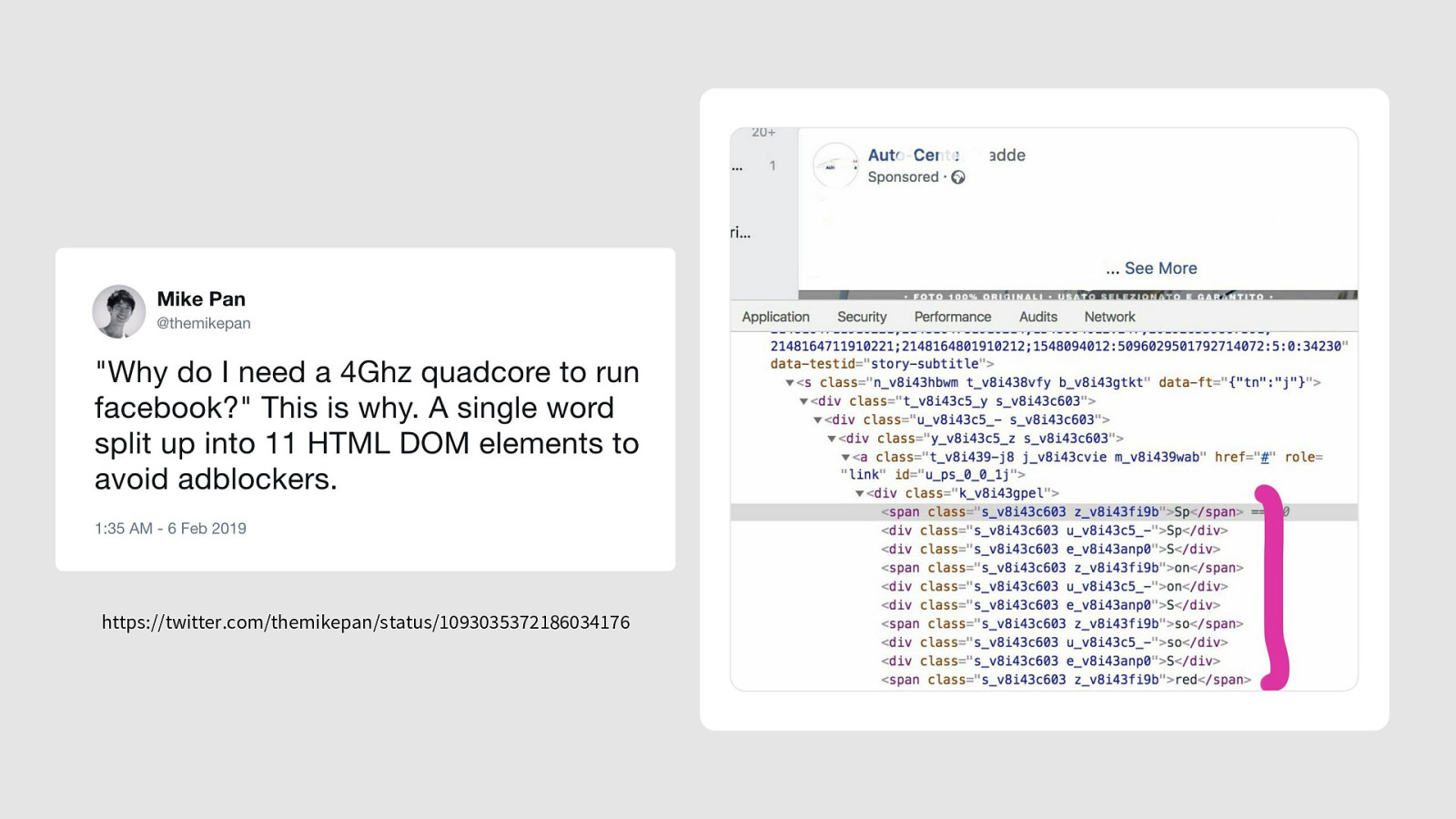

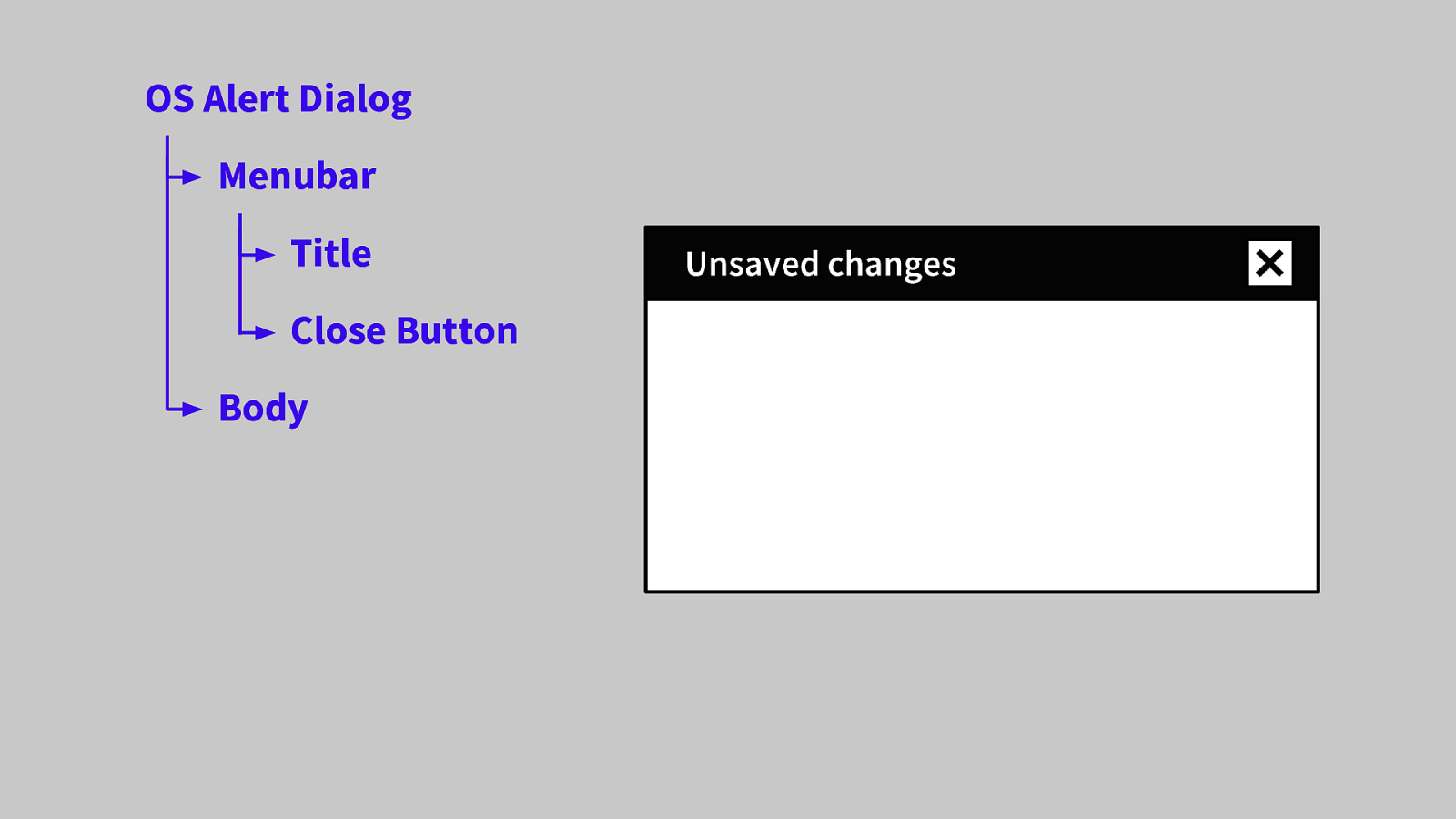

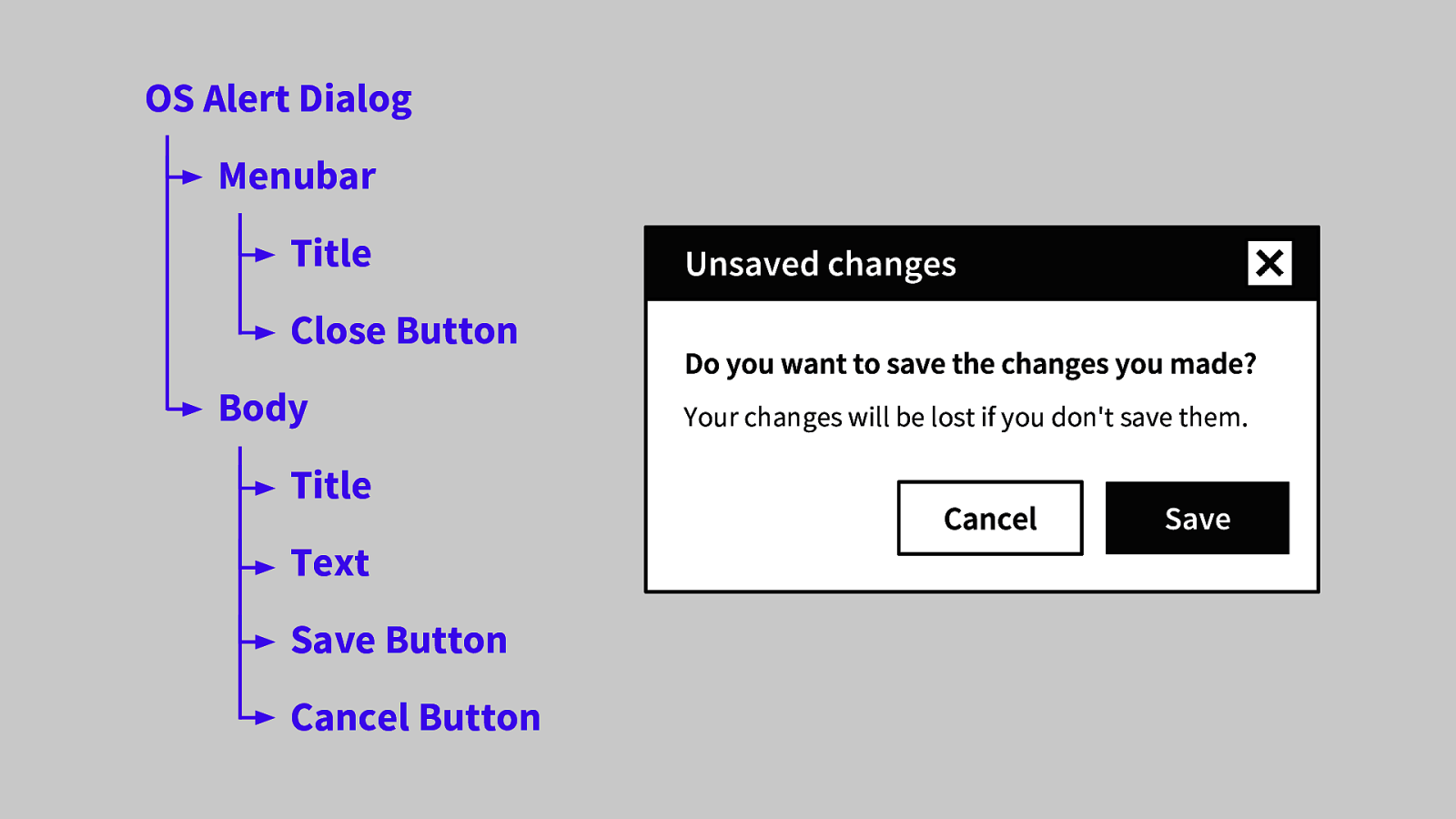

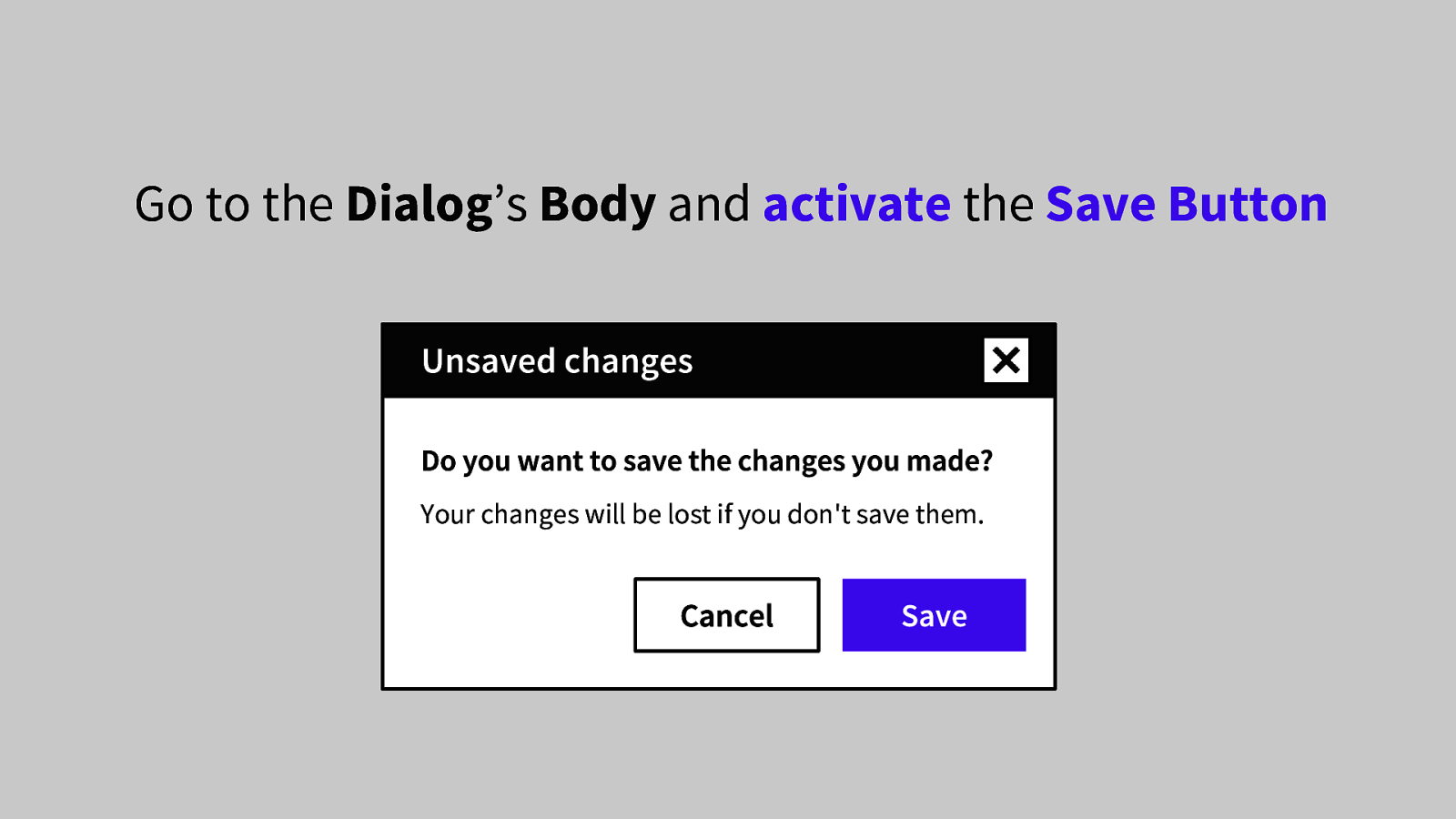

-So, this might seem a little pedantic, but please bear with me for a bit