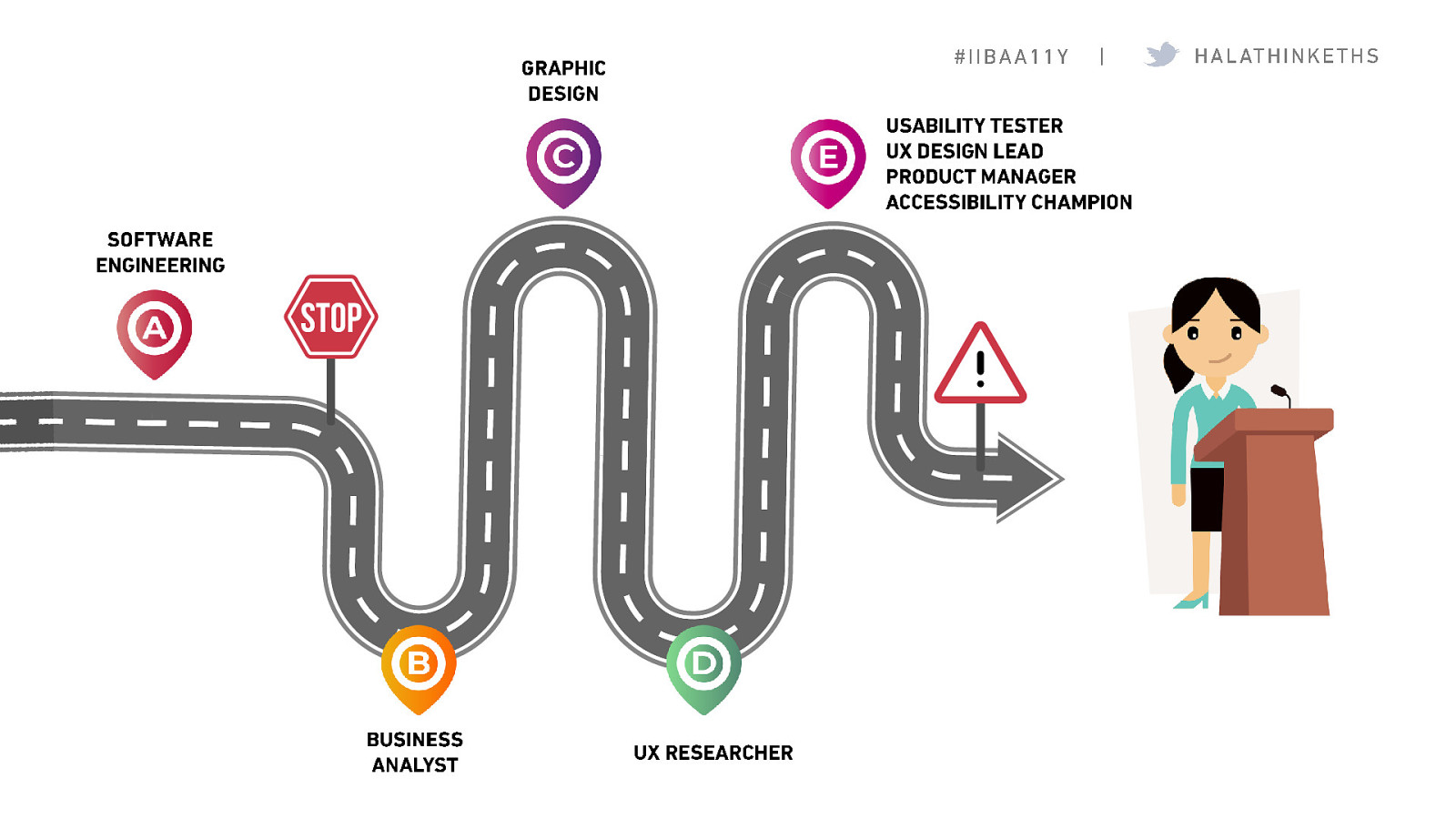

Thank you for sharing! Over the course of my career, I feel like I have had the opportunity to try out a lot of those roles.

A: My journey began in undergrad as a software developer. When I graduated, I realized studying SW nurtured a lot of my critical thinking skills, which would later be ‘critical’ for my role as a product manager. At that time though, I felt two things were missing: 1. client interaction, 2. decision-making power.

B: I took a hard right turn into my job as a BA for a NATO contractor.

C: At the same time, I was teaching graphic design at a local university; it had always been something I dabbled in on the side and felt like an outlet for creativity.

D: Finally when I had enough of a daily 4 hour commute in Dubai, I applied to study Human-Computer Interaction at the University of Waterloo, which was an amalgamation of my interests hitherto. I worked as a UX researcher at the university for 3 years, really sharpening my design thinking skills.

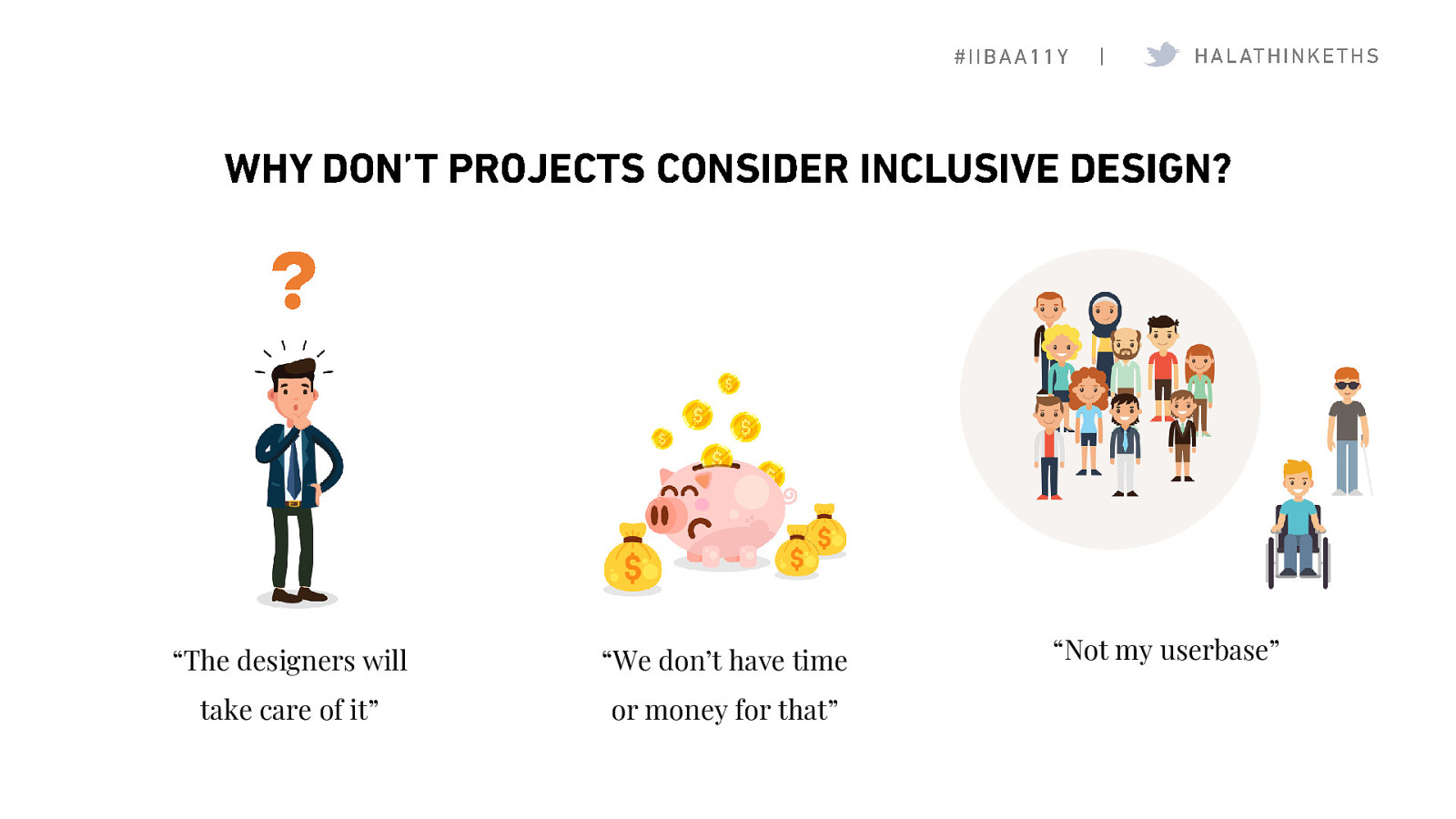

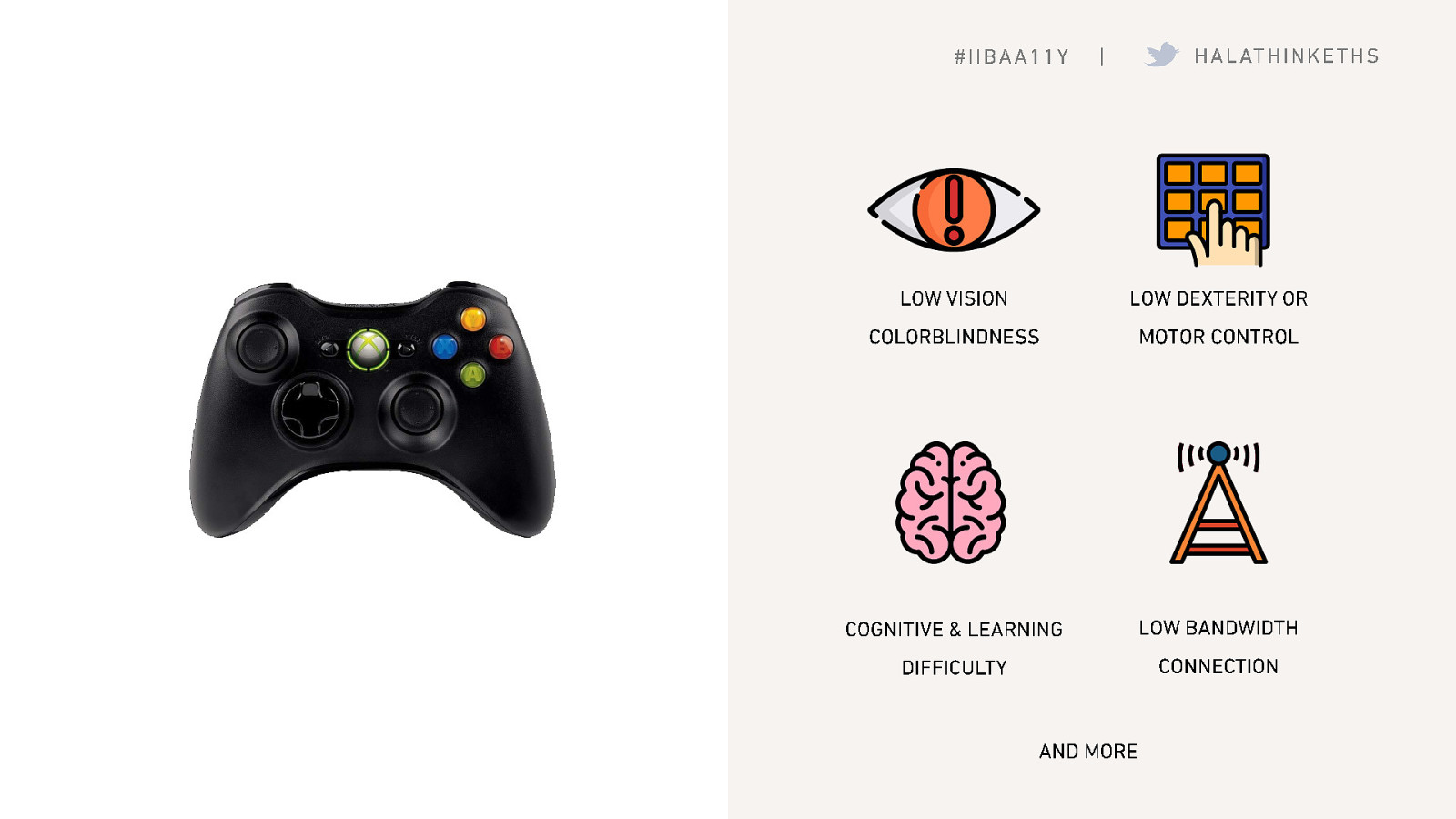

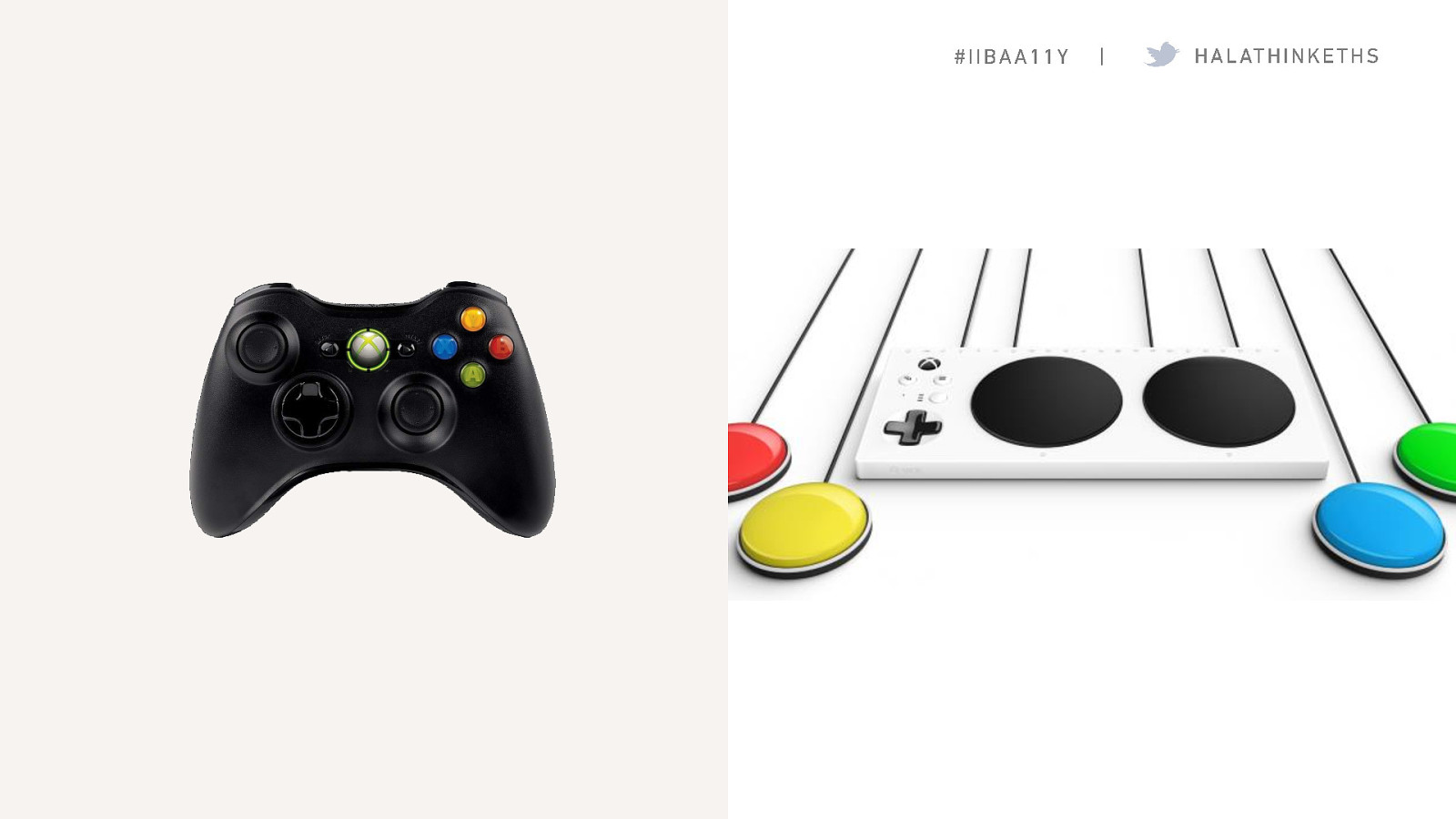

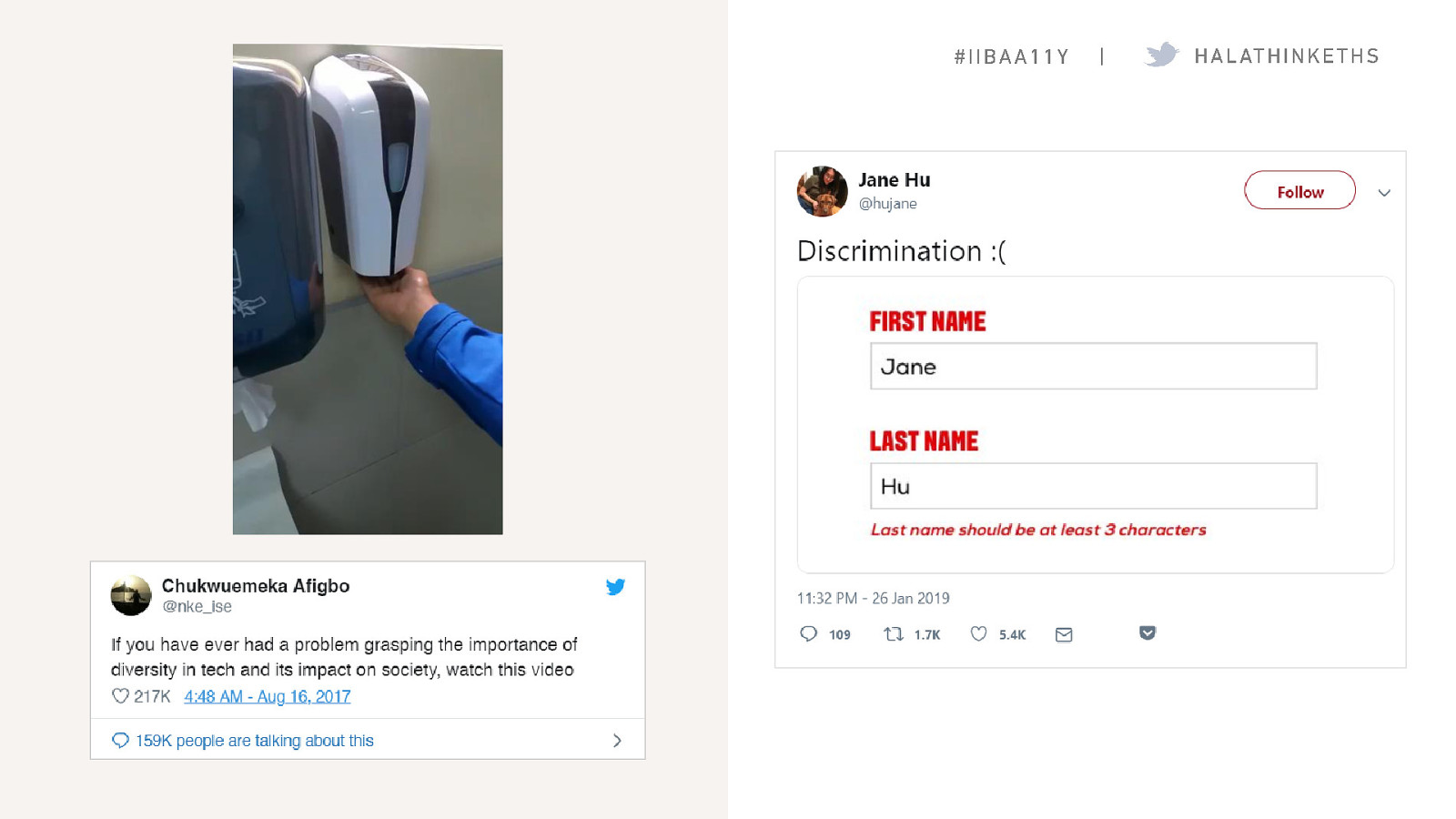

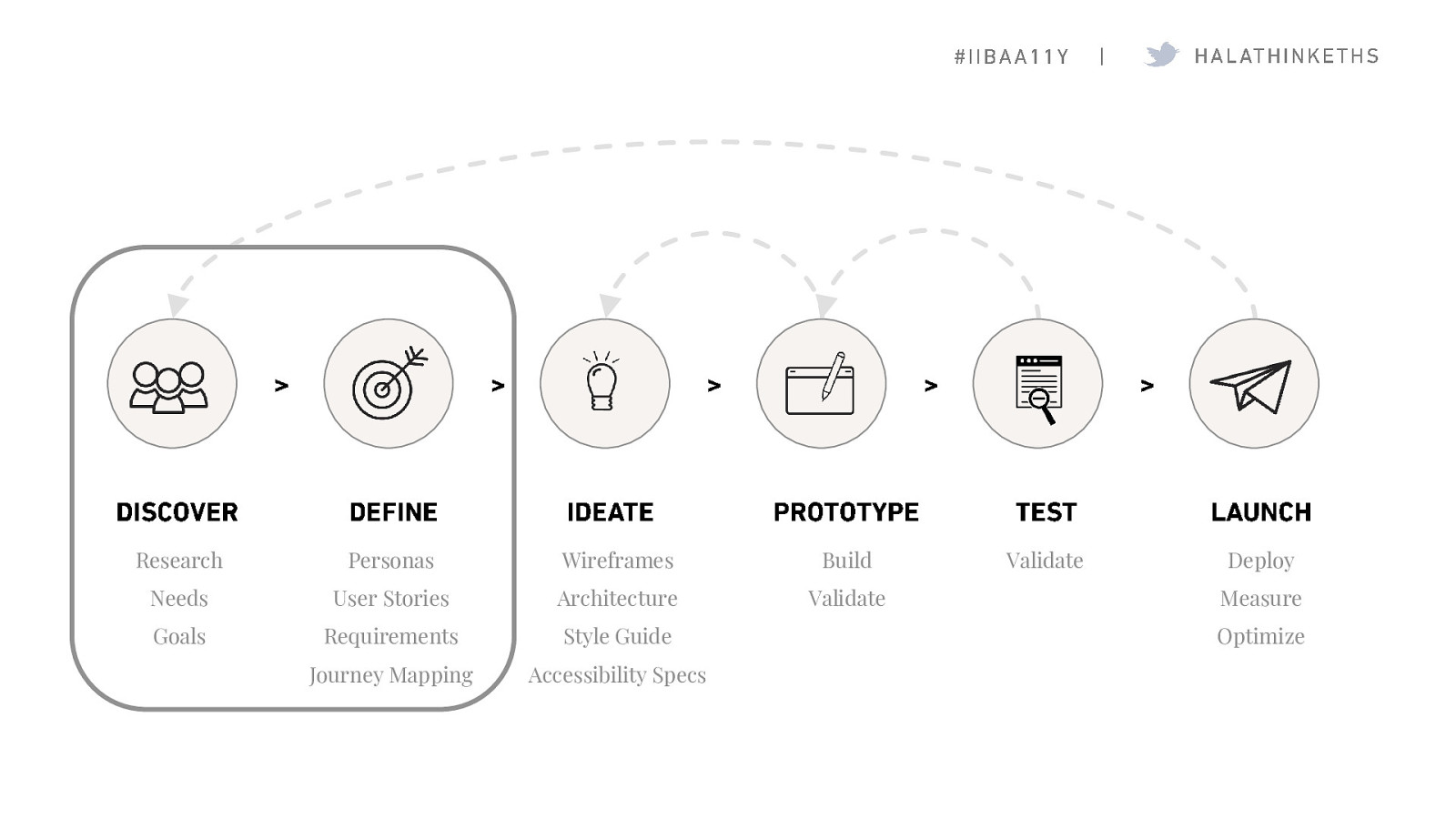

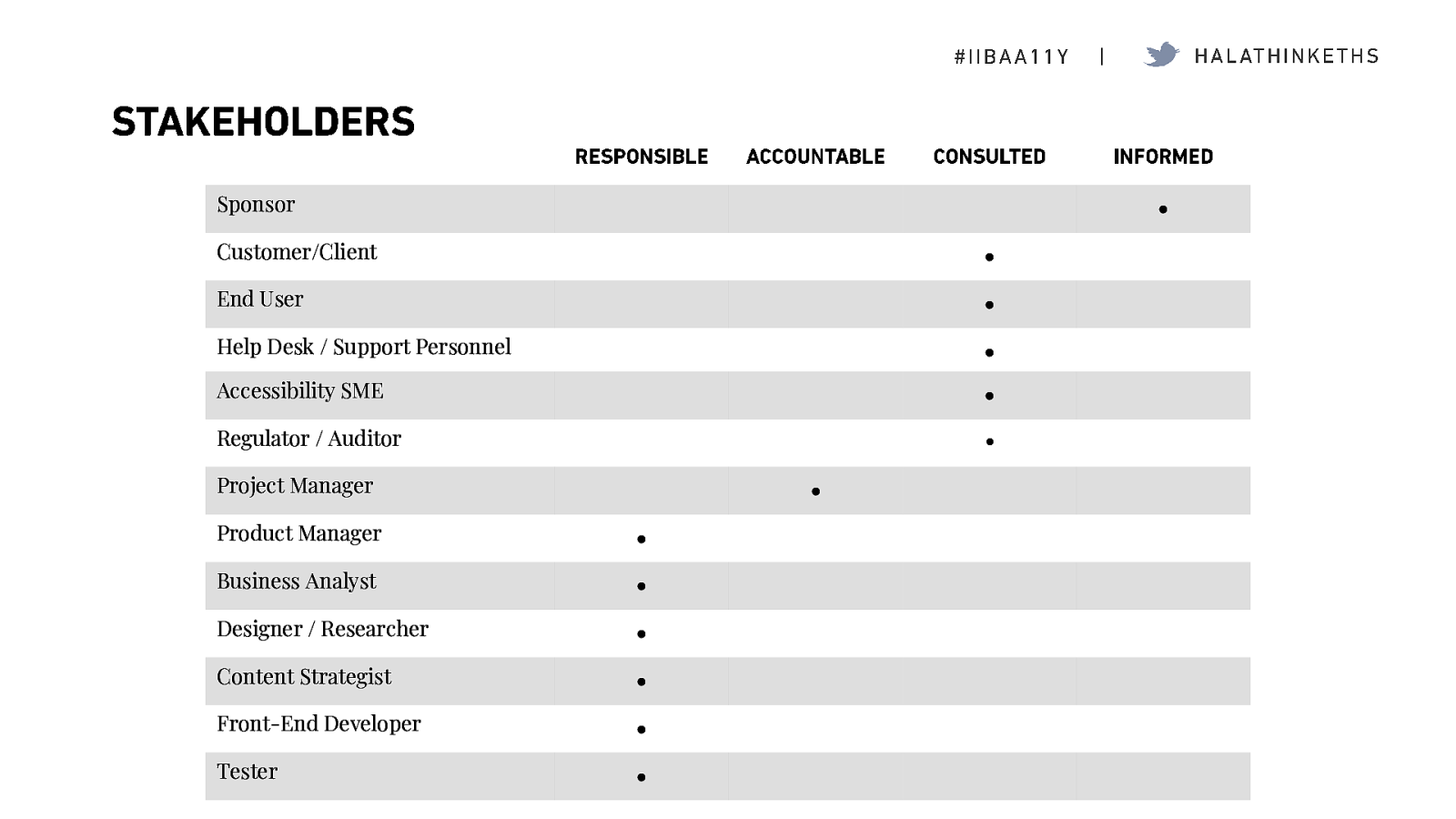

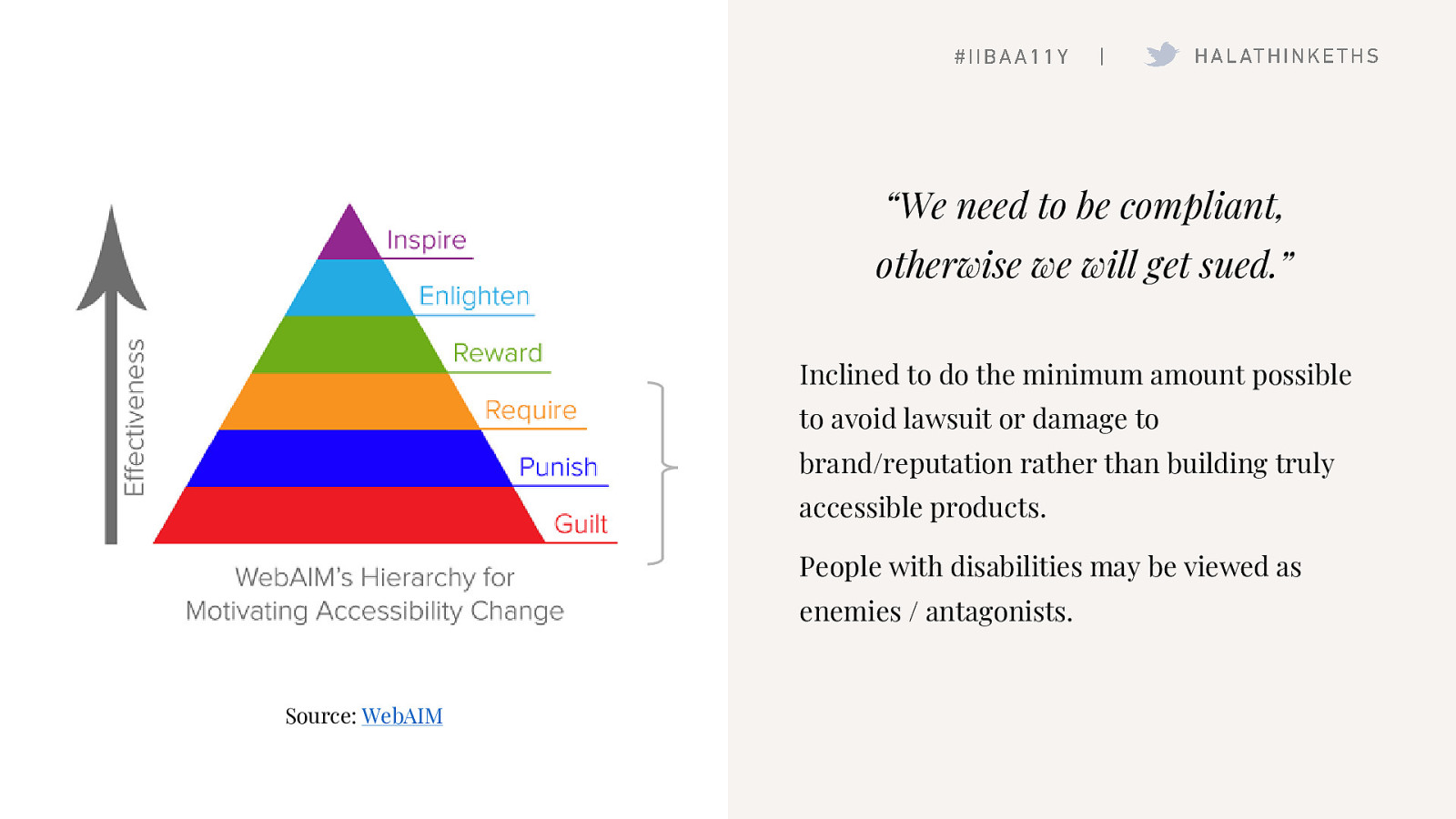

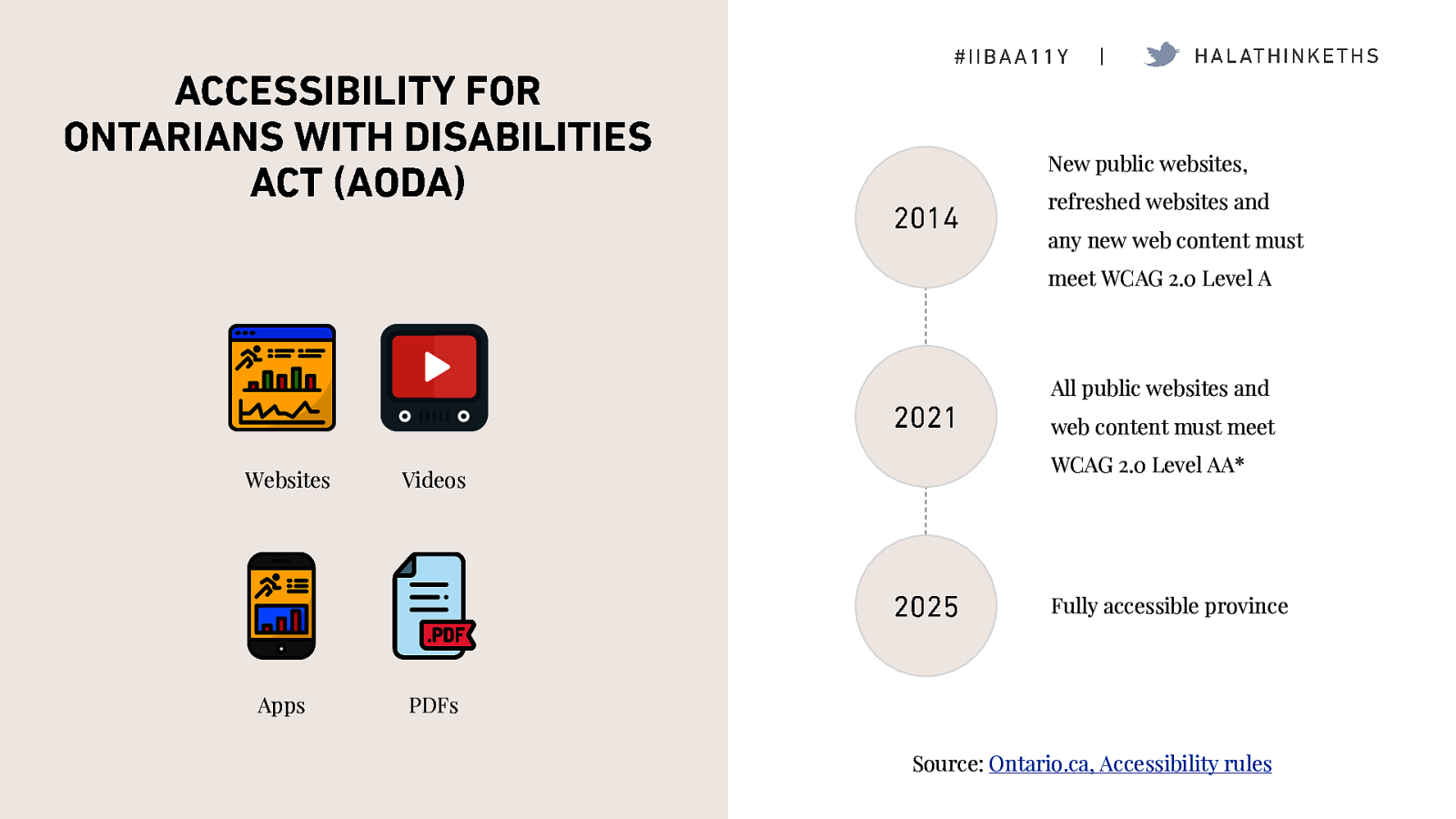

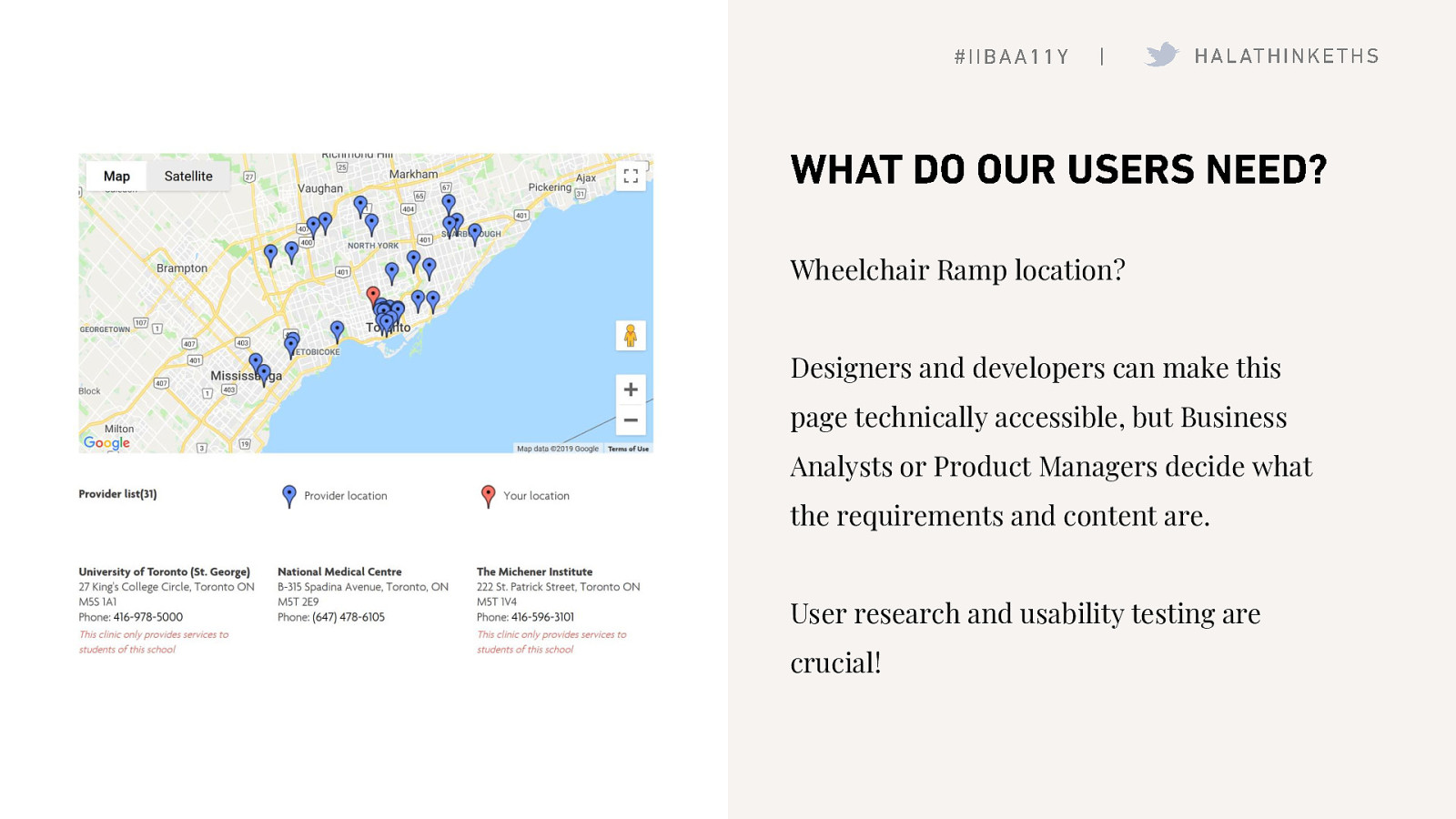

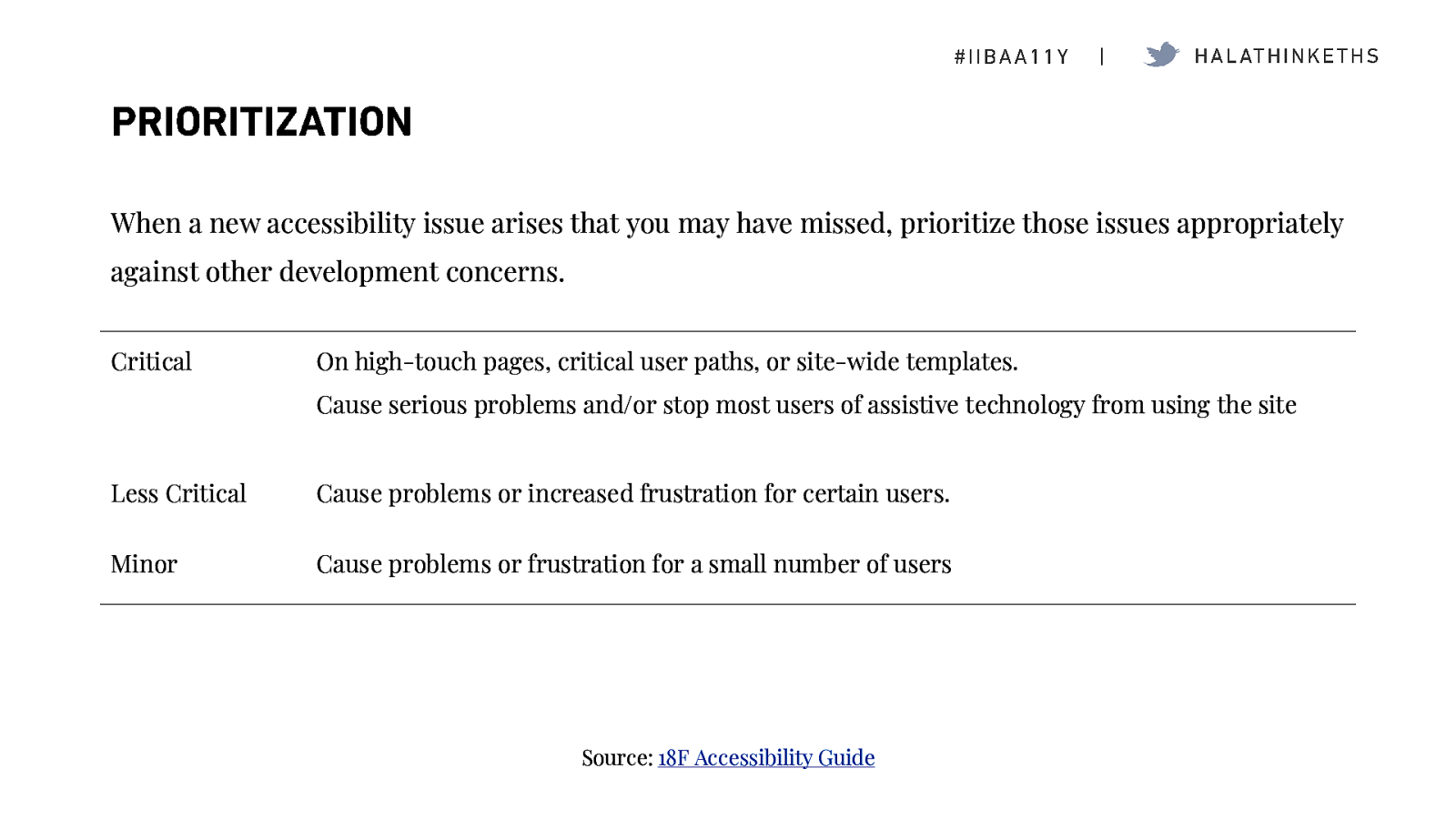

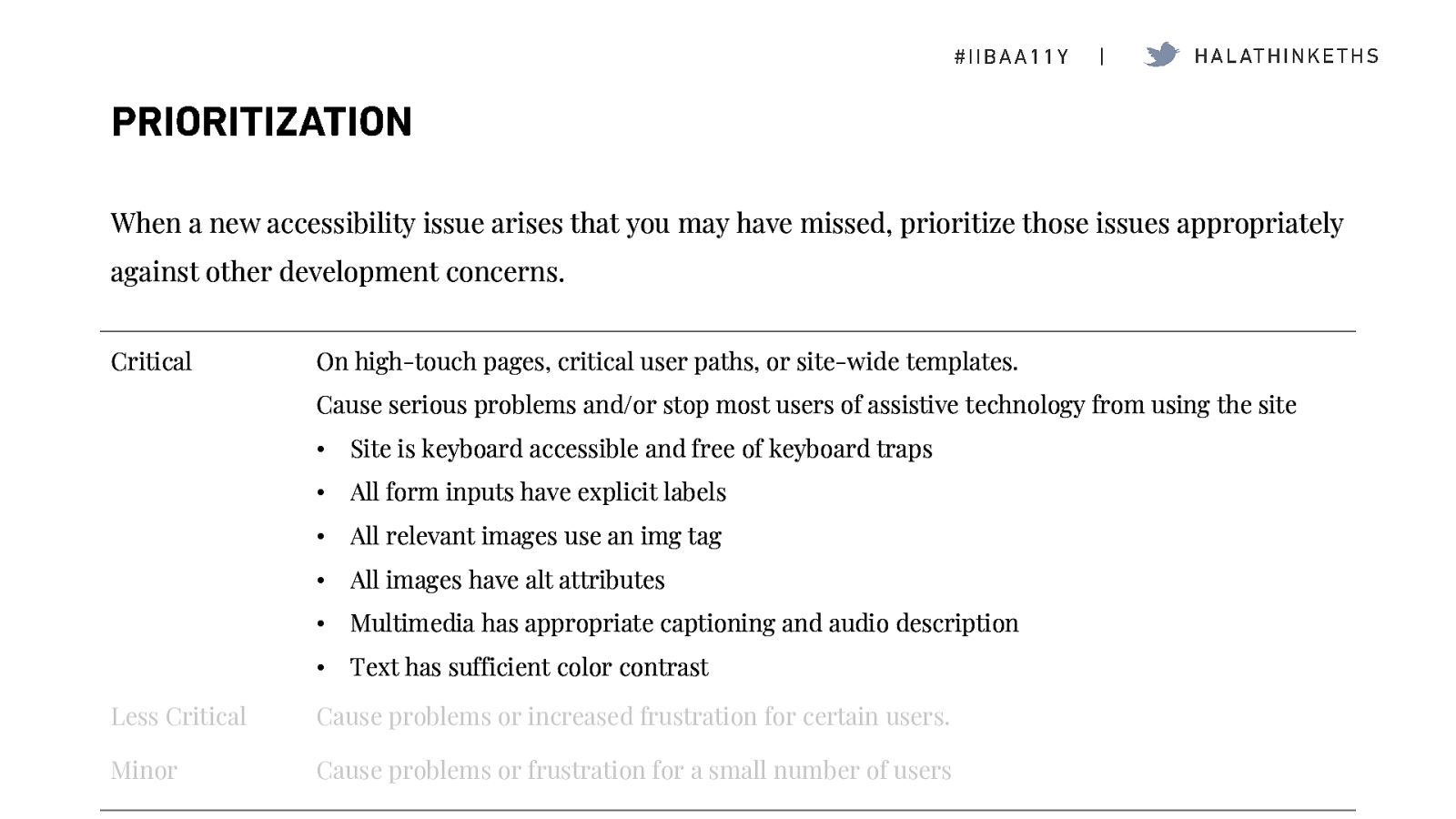

E: I then joined Consulting when I moved to Toronto where I have been able to try out this spectrum of roles. Since I was predominantly working with a government clients, I came across ‘accessibility’ which was part of everyone’s job, but no one knew anything about it and it was just considered this ‘black box’ of regulation.

I have an amazing mentor, Jan Richards, who helped shaped the one big realization, that I’m here to share with your today…