When you work in design or tech, you work in politics. You might not like it. Or you might not know it. But you do. And I’m about to tell you why.

A presentation at CSS Day in June 2022 in Amsterdam, Netherlands by Maike Klip

When you work in design or tech, you work in politics. You might not like it. Or you might not know it. But you do. And I’m about to tell you why.

But first let me introduce myself properly. My name is Maike Klip. This is my contact information and feel free to reach out. I will publish my slides on noti.st.

Let’s start with a quick recap of my career so far. I studied Journalism and after I worked as a freelancer. I became a civil servant for the Dutch government a couple years ago. As you can see that has been quite an identity change for me.

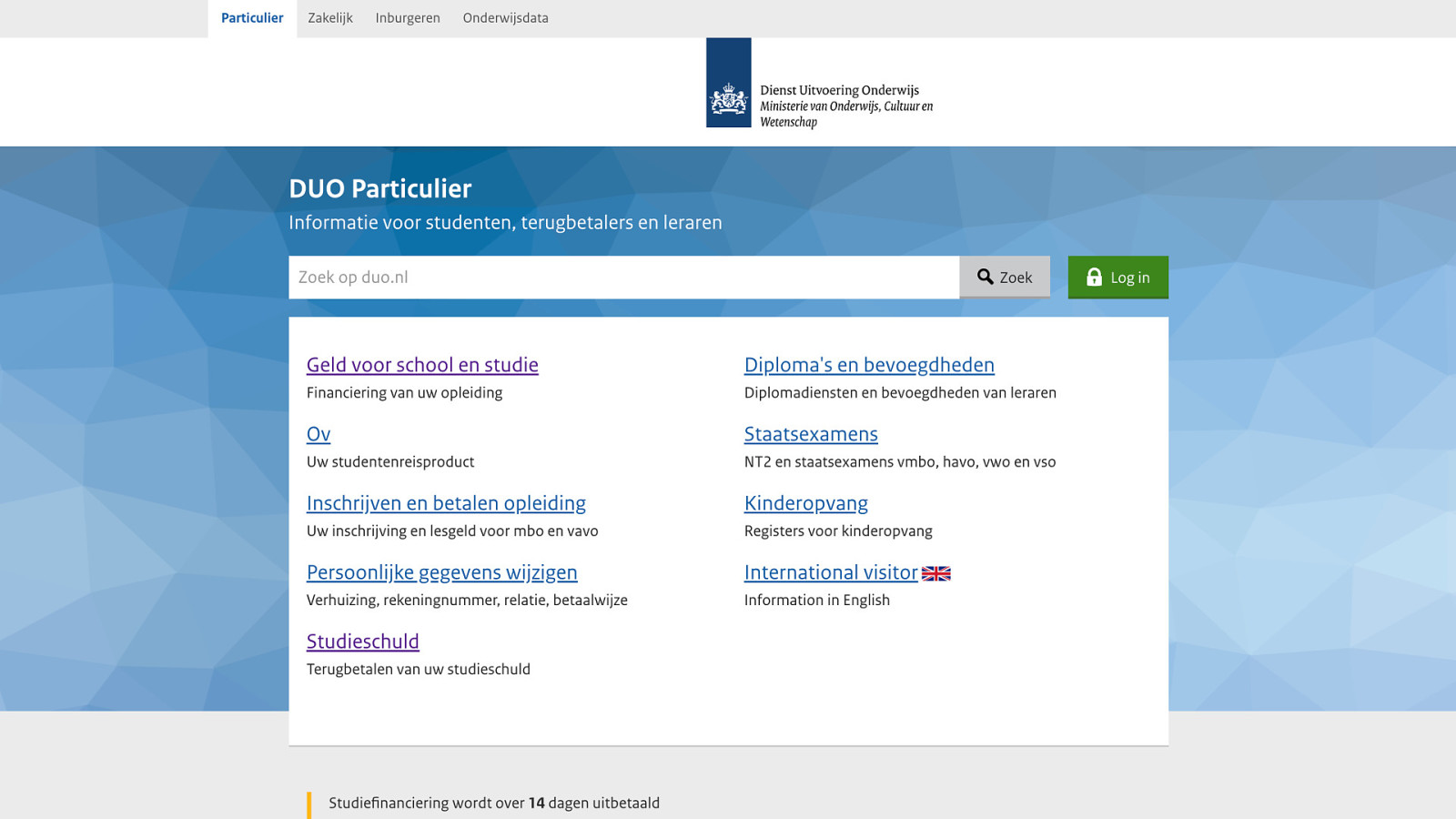

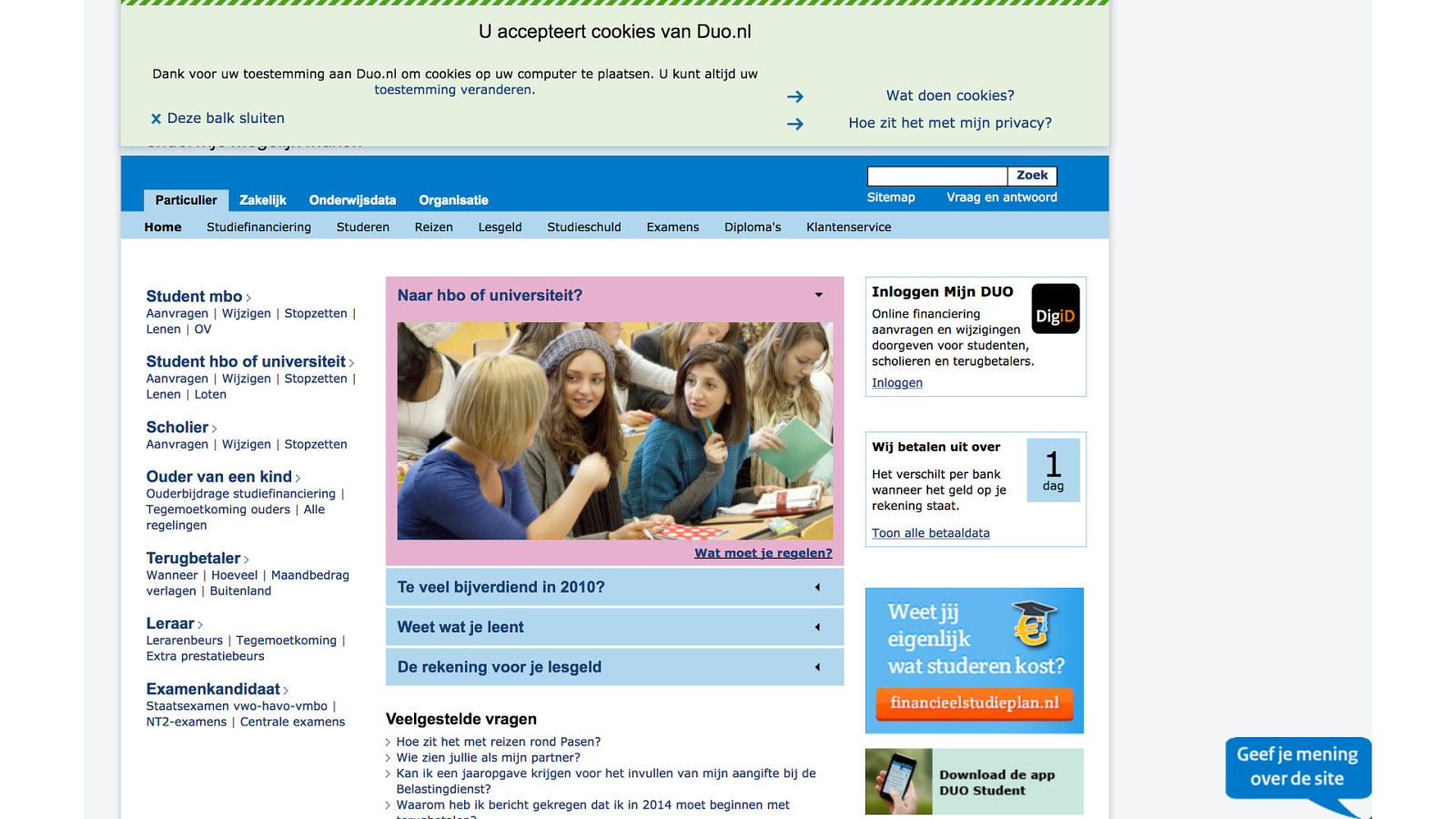

I started as a user researcher in government almost ten years ago. I worked at the Executive Agency for Education, in dutch better known as DUO where students apply for student nance. I was one of the rst UX researchers. That can be very exciting as you can help design what that role should be in your organisation. fi fi So my job is not really what’s ‘in’ the computer, but what happens around it. How people interact with what you made. But we’re at cssday, so let’s do look at some screens.

For most people who have to deal with DUO this is our home. This is ‘the door’. In the 8 years that I have worked here we redesigned the digital journey for students, refugees and people working at schools. Behind this door you find more than 400 digital applications.

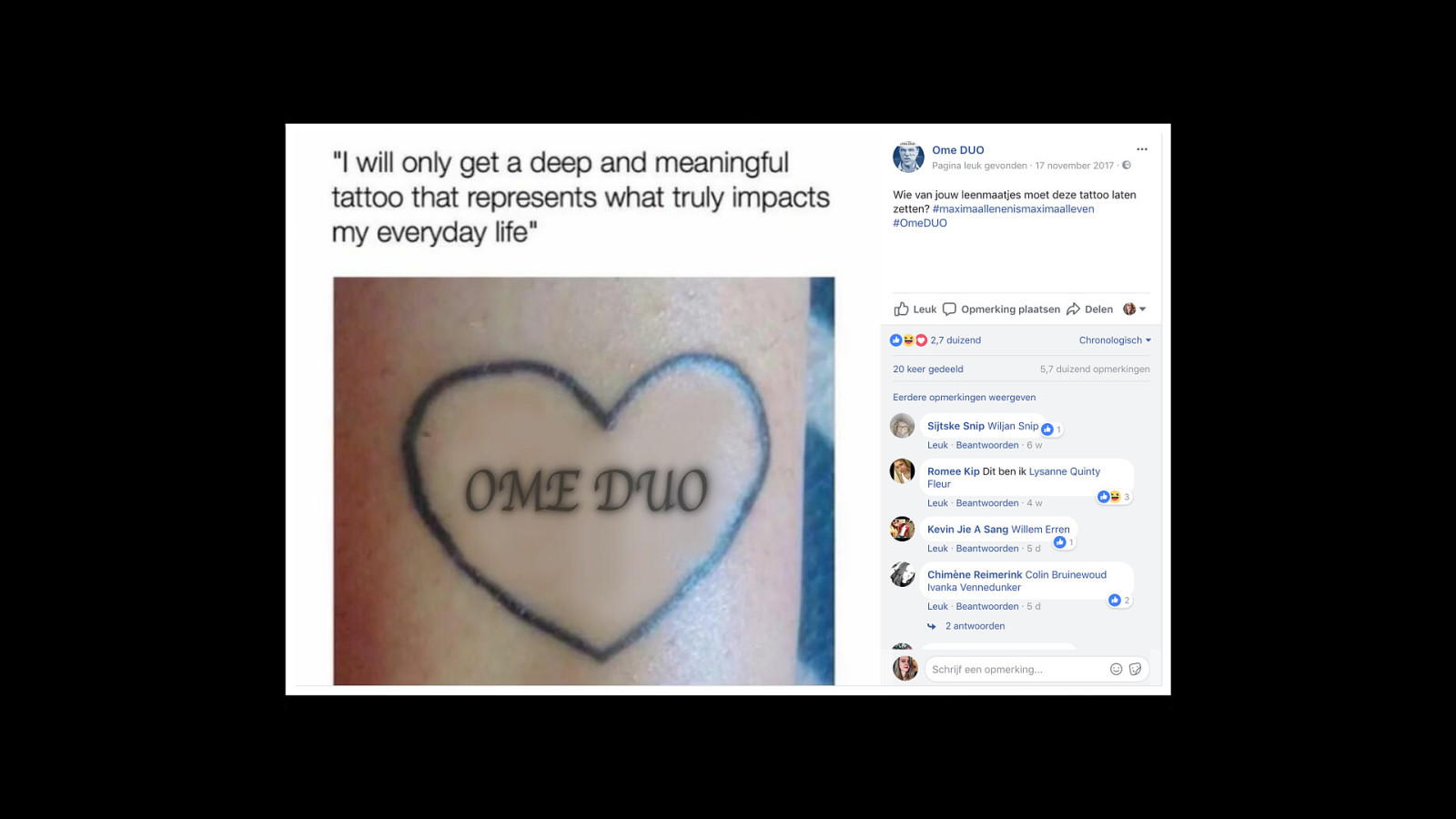

We talked and tested with a lot of users. We went to schools, to public spaces, met people at their homes and invited them in our offices. We got used to student language, memes and also the trouble of having student loans.

Just for fun let’s take a trip down memory lane looking at some old websites of DUO.

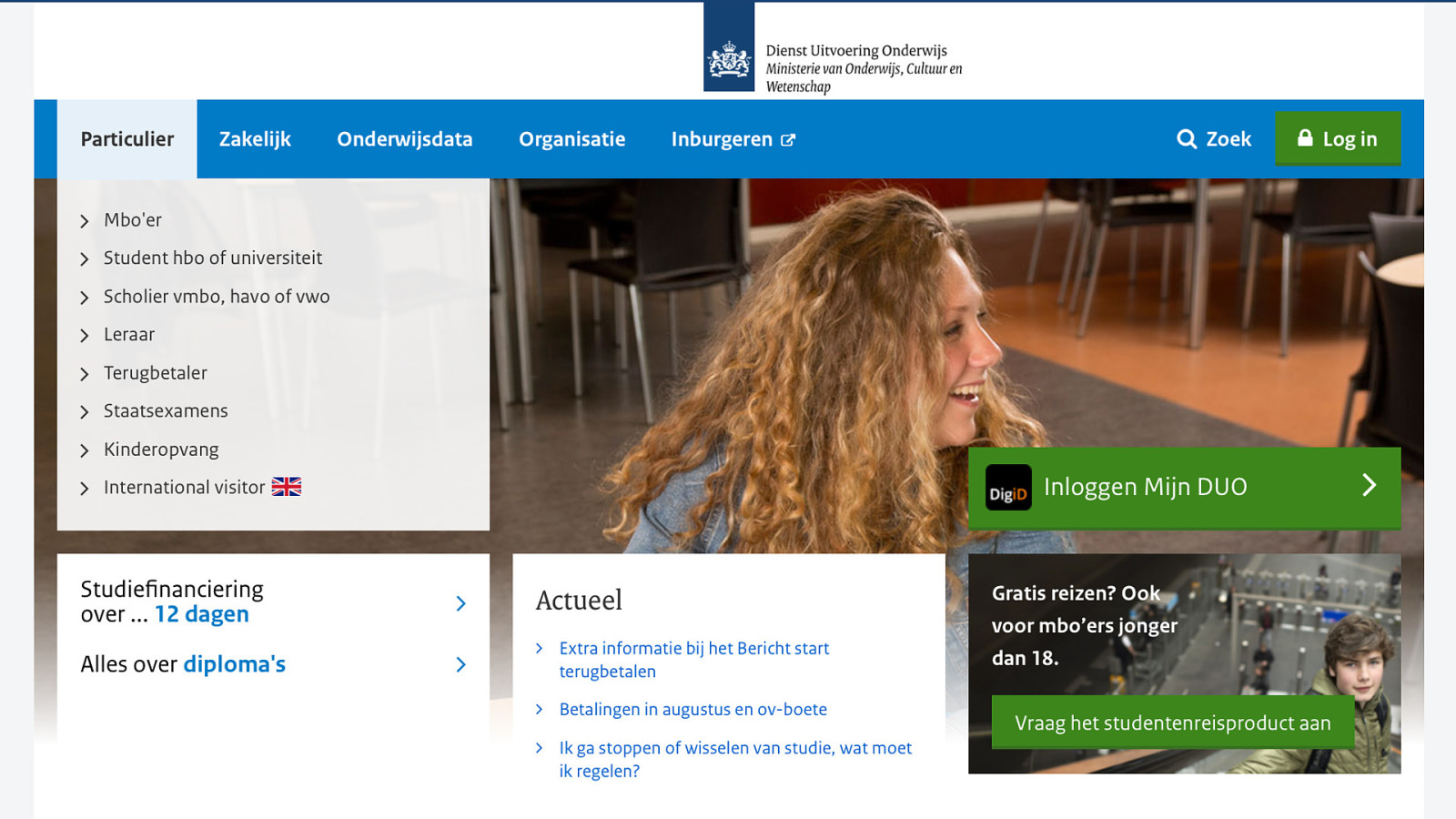

Here you had to first tell us who you are before we gave you the information for that target group that you fit. But a lot of people didn’t know in what group they belonged. So we changed that to the more task oriented website I just showed you. We had this one from 2012 to 2018.

Before that we had this gem. Very packed with information. And of course a very nice side bar, I guess this was very popular then. I’m not sure right now what the dates for this site was.

This one is from 2005. This was my website when I was a student and had to apply for student finance.

Here is another great one from I think the late 90’s, early 00’s? And I am just guessing because of the boy with the eyebrow piercing and the gloomy filters on the photos.

This was in 1997 and DUO was one of the first governmental agencies with its own website. I’m not sure what you could do on this website as I myself was 8 at the time and of course not a user back then.

But what a gem hey!

Back to my introduction, in 2018 - 2020 I did a design research project called the Compassionate Civil Servant, or in Dutch De begripvolle ambtenaar where I photographed my colleagues working in digital government as a compassionate civil servant. Together we re ected on our biases and the role empathy should have when making websites, portals and automated decisions.

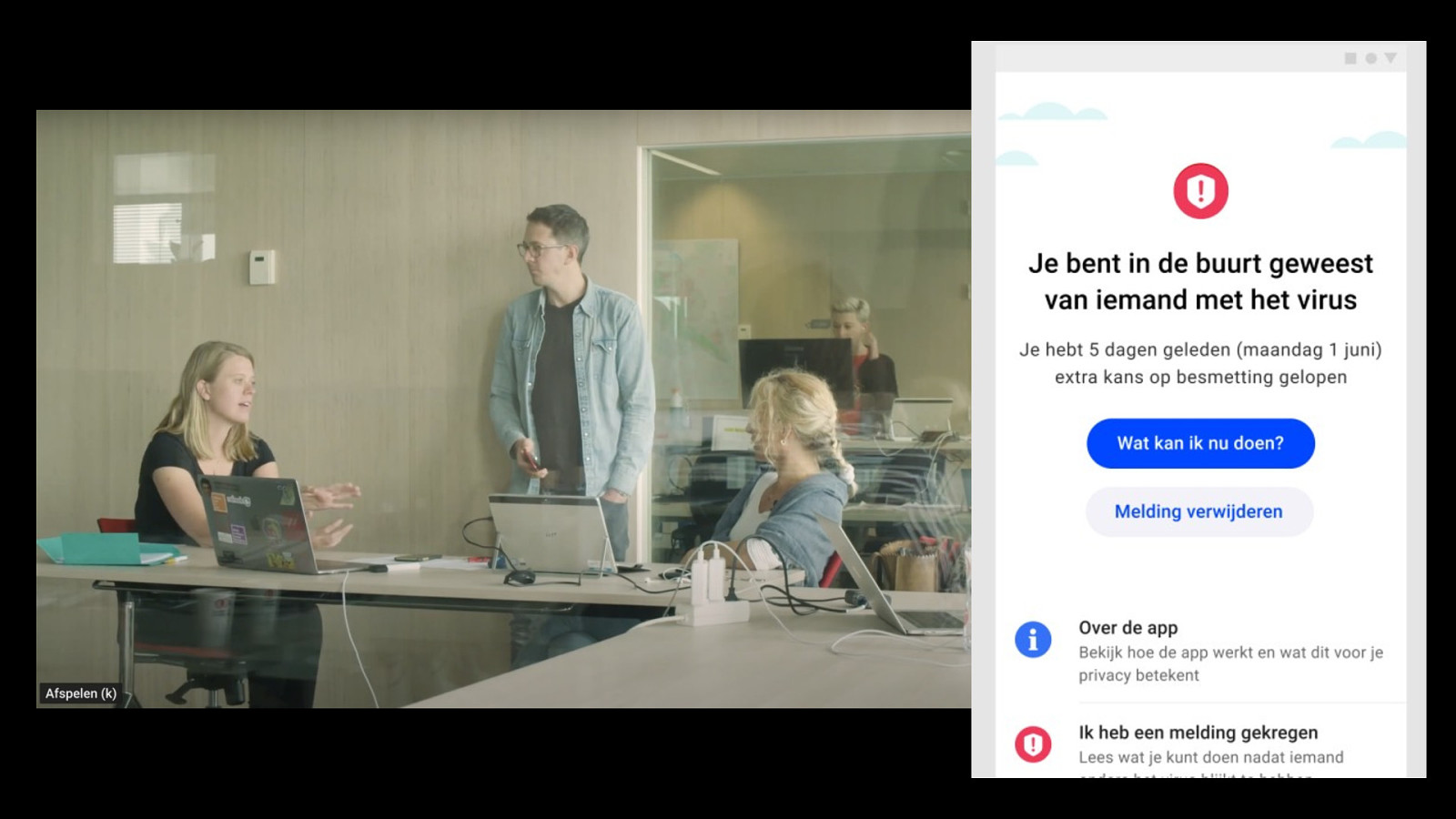

When the corona crisis started in 2020 I joined the design team to work on one of the dutch corona-apps. I visited the GGD’s, the local health organisations to research how contact tracing could benefit by the use of an app.

Last year I worked at the National ombudsman as a research leader. I wanted to zoom out a bit from just the digital government and learn more about the interaction between citizens, government and politics in general. I did projects about the consequences of the gas extraction in Groningen, I researched the social aspects of the energy transition and I visited the South of Limburg where a year ago unexpected floods cause a lot of damage but there is still not a good arrangement for damage repairs for citizens. My year there ended a couple weeks ago.

Right now I’m working on a project about transparent government algorithms and I’m cooking up a new project that I’d like to start this fall.

Three years ago I did an experiment in Rotterdam. I tied a yellow rope around my waist and asked people how they wanted to be connected with me, the government. I had a couple of great, also confronting conversations. Some of them came very close, this man at one point stepped into my personal space, others stayed very far away. If only the government was a pretty blonde woman all our problems would be solved.

In every conversation I have with citizens about government and what they expect is that they hope government understands them and their situation. And when things get rough government will have some compassion. This picture shows a lot of the complexity from the stories I heard from them.

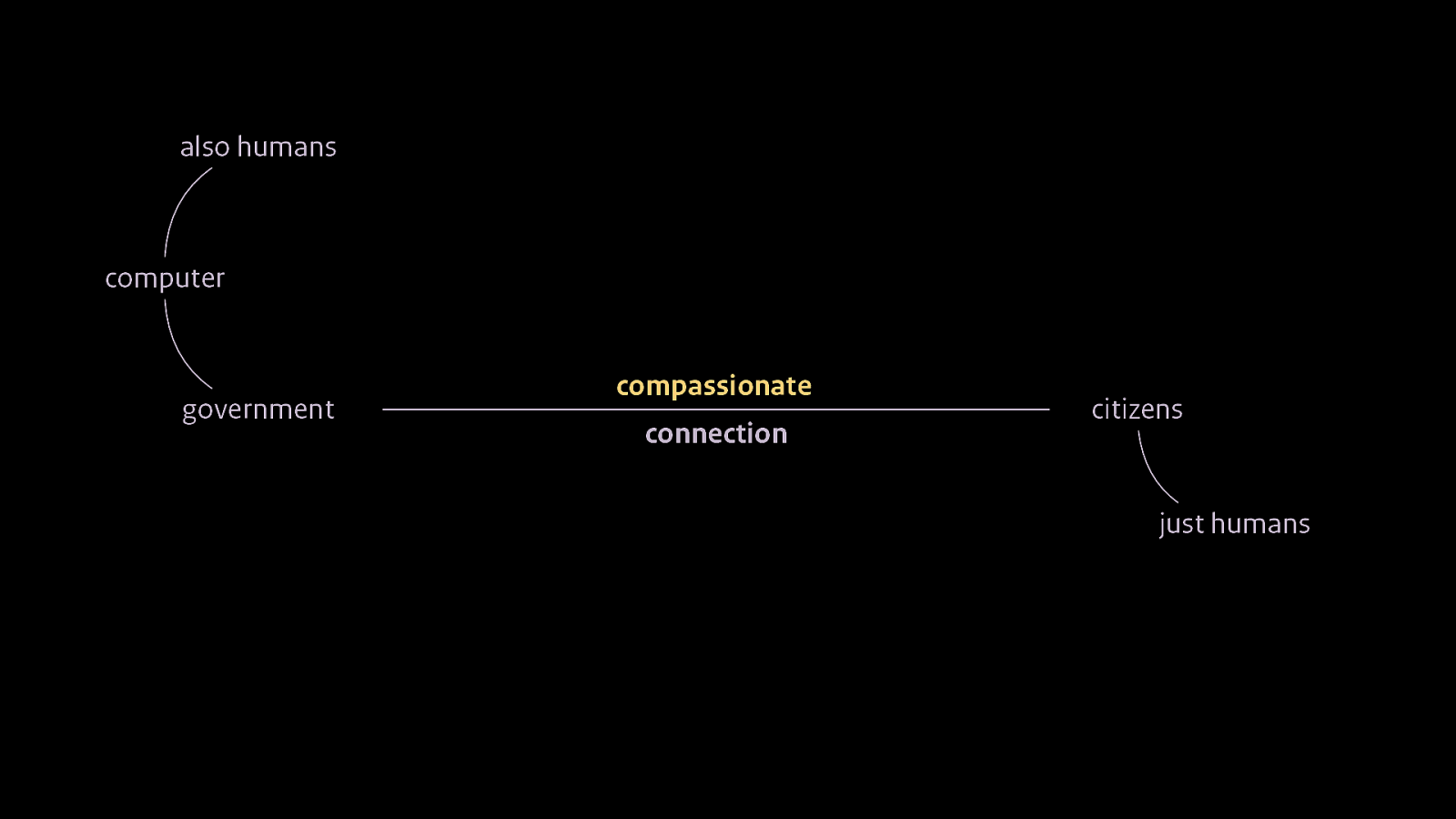

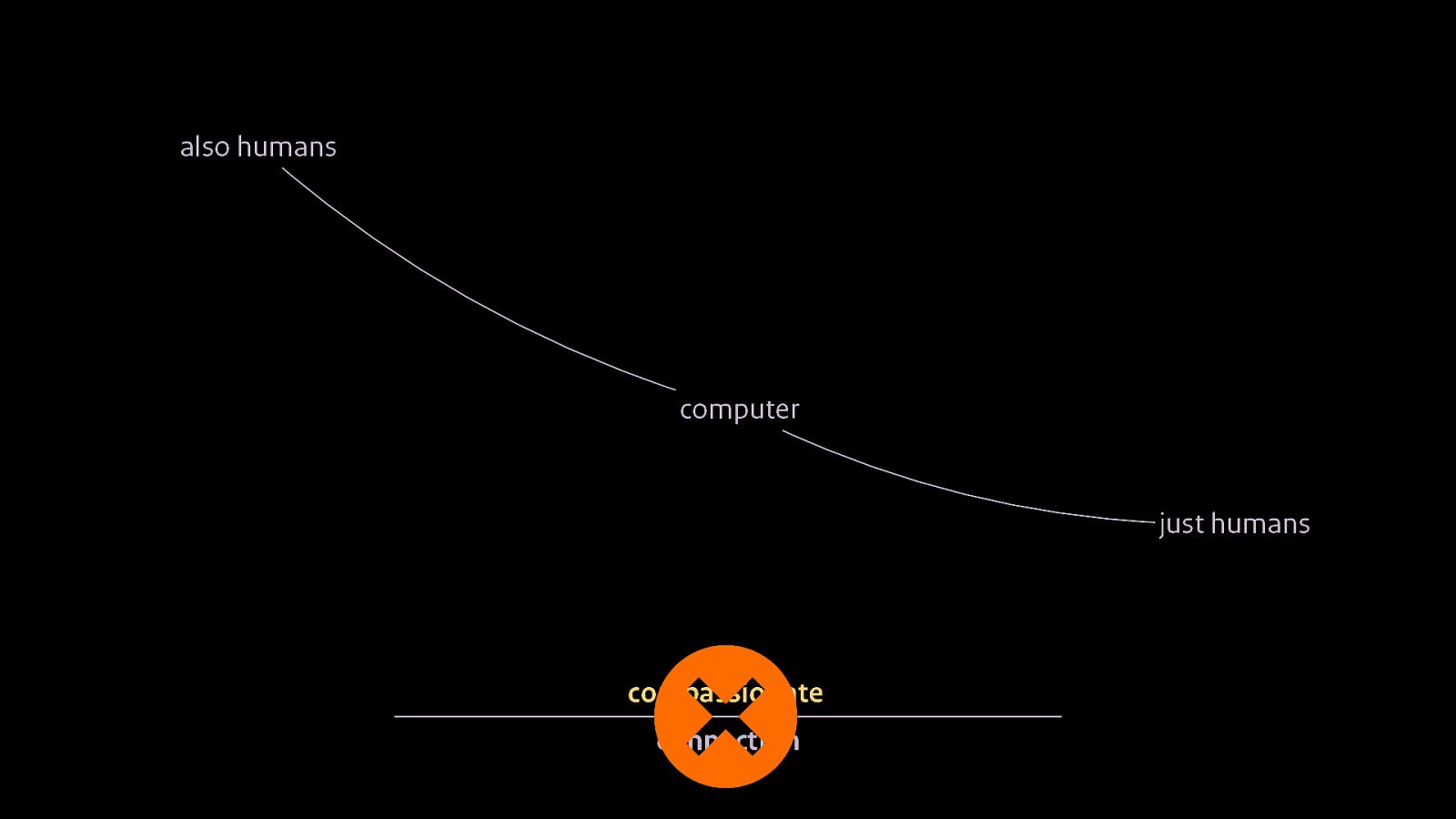

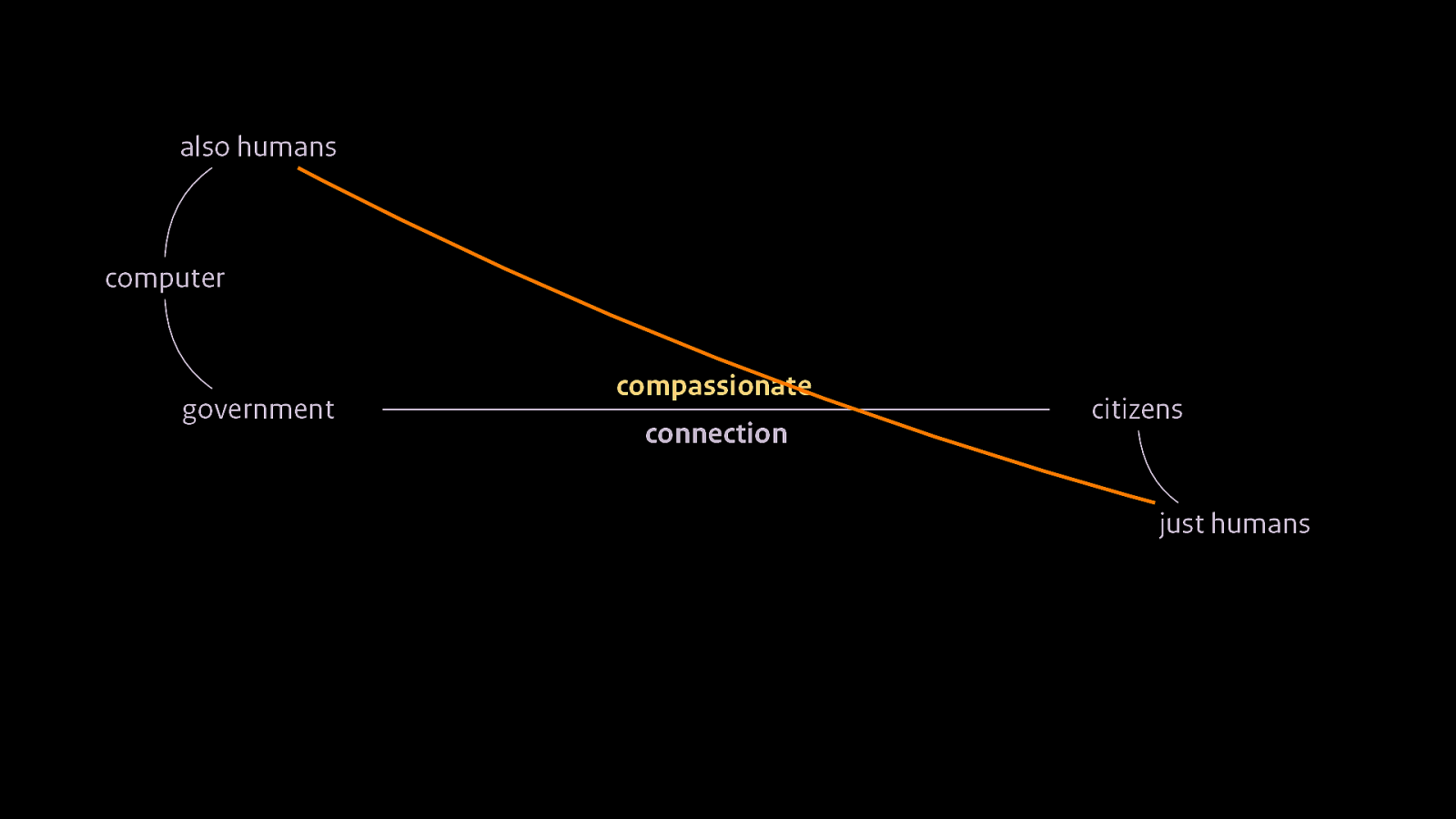

In all my work this basic principle is leading. How can we, as government can have a compassionate connection with citizens. But there’s a strange thing happening with this relation.

Citizens are humans of course. But the government has become a computer. You hardly interact with government officials anymore when you have to take care of something regarding your relation with the government. You go to websites, log in portals and ll out online forms. You receive confirmations by email and receive money, or pay, automatically and/or online. Only when things go wrong you start looking for someone to call. It is then you figure out that just calling up the government isn’t an easy task anymore.

But this computer we call government is made my humans. Your typical government official isn’t someone at a desk pushing paper anymore, it’s someone working in IT, a developer or a designer, it’s someone like you.

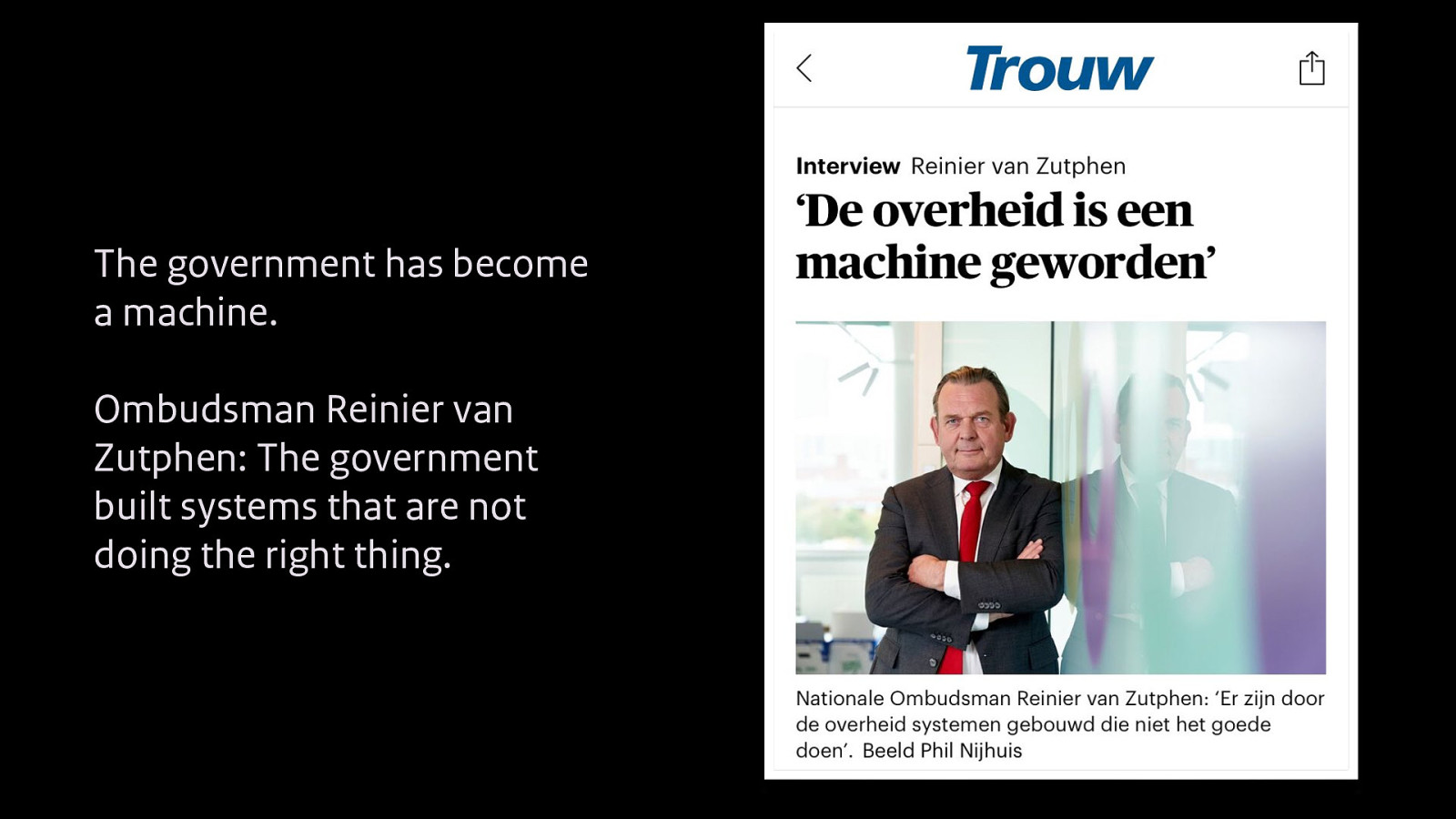

The government has become a machine. Ombudsman Reinier van Zutphen: The government built systems that are not doing the right thing. Reinier van Zutphen, the national ombudsman also notices in the complaints he gets from citizens that the government has become a machine. But he continues to say that we built systems that are not doing the right thing anymore.

These humans on both side of the connection rarely talk to one another. Citizens have almost never personal contact with a government official, maybe sometimes after waiting in call for many many minutes We automated almost everything in government. ffi ffi ffi And government o cials, we hardly ever leave our o ces to ask for feedback or to just talk to one of our users and ask how they experience what we made.

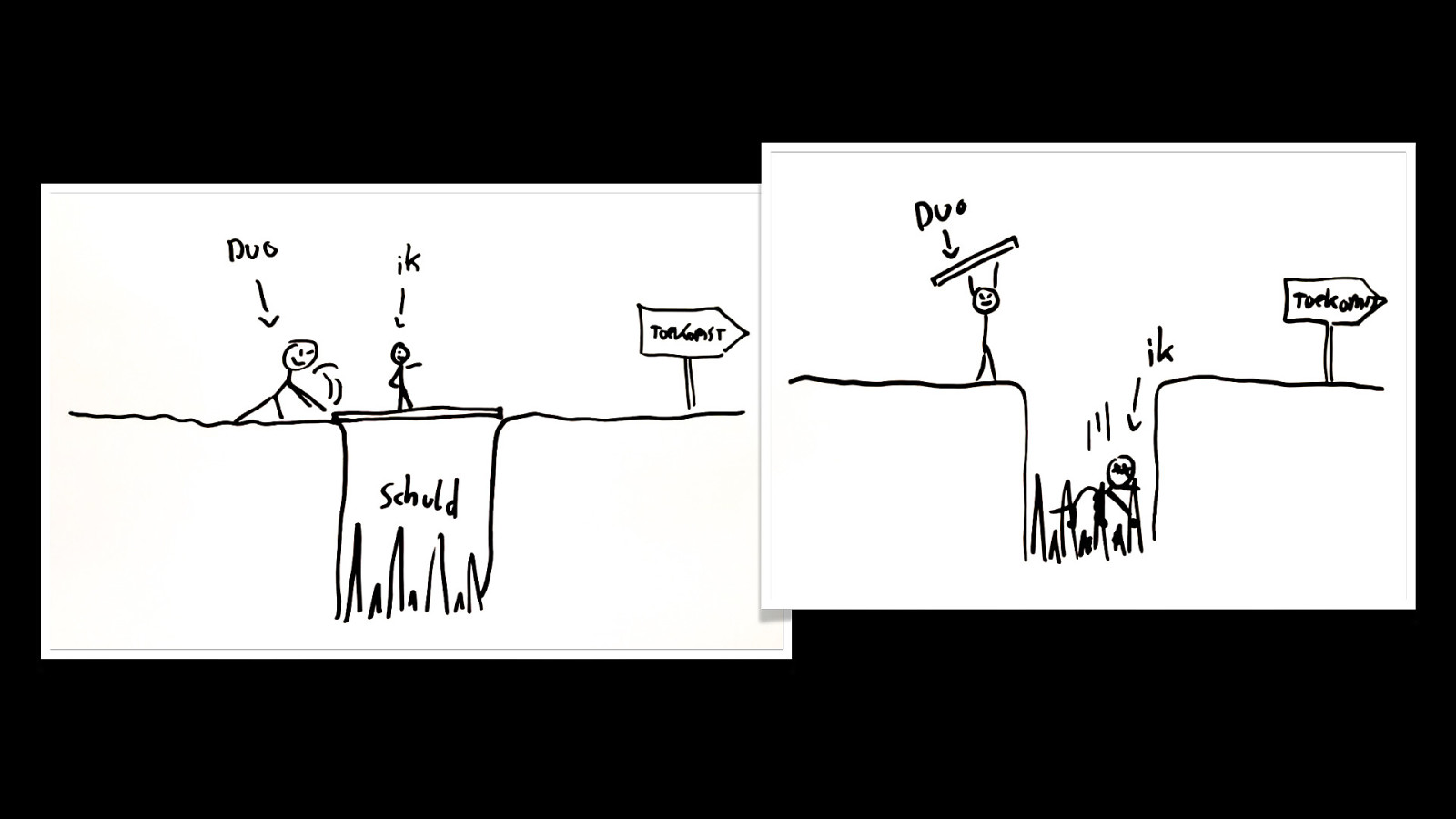

And it shows… a lot of citizens don’t feel understood by our government. They don’t experience a compassionate connection at all. For example students. These drawings are from a research study about student debt I did with students.

So I wanted to know what happens if we reconnect makers and users in my organisation. I did the same experiment with the yellow rope I used in Rotterdam and I invited my colleagues and some of our main users: students who applied for student finance.

This is Britt, she is a student. And that is my colleague Ineke at DUO. At the time she was the product owner of duo.nl. How do you feel connected to a student, I asked here? This is her answer.

(video only in presentation, I’m sorry)

I did this experiment with a lot of my colleagues, all working on our digital products. Everybody had a different experience and a different answer.

My hypothesis was that the farther away someone works from the interaction level, the more distance they experienced. But that was not the case. Everybody answered based on who they were, now and as a student, and based on how they looked at the world.

Technology is not a higher power, not a deity, nor is it something that arises by itself. Technologies are cultural artifacts. Technology is people work. We design technology and technology reflects our cultural and political values. It matters what choices are made when developing technology and who is behind the drawing board.

Marleen Stikker, director from Waag Society here in Amsterdam writes in the book The internet is broken (2018).

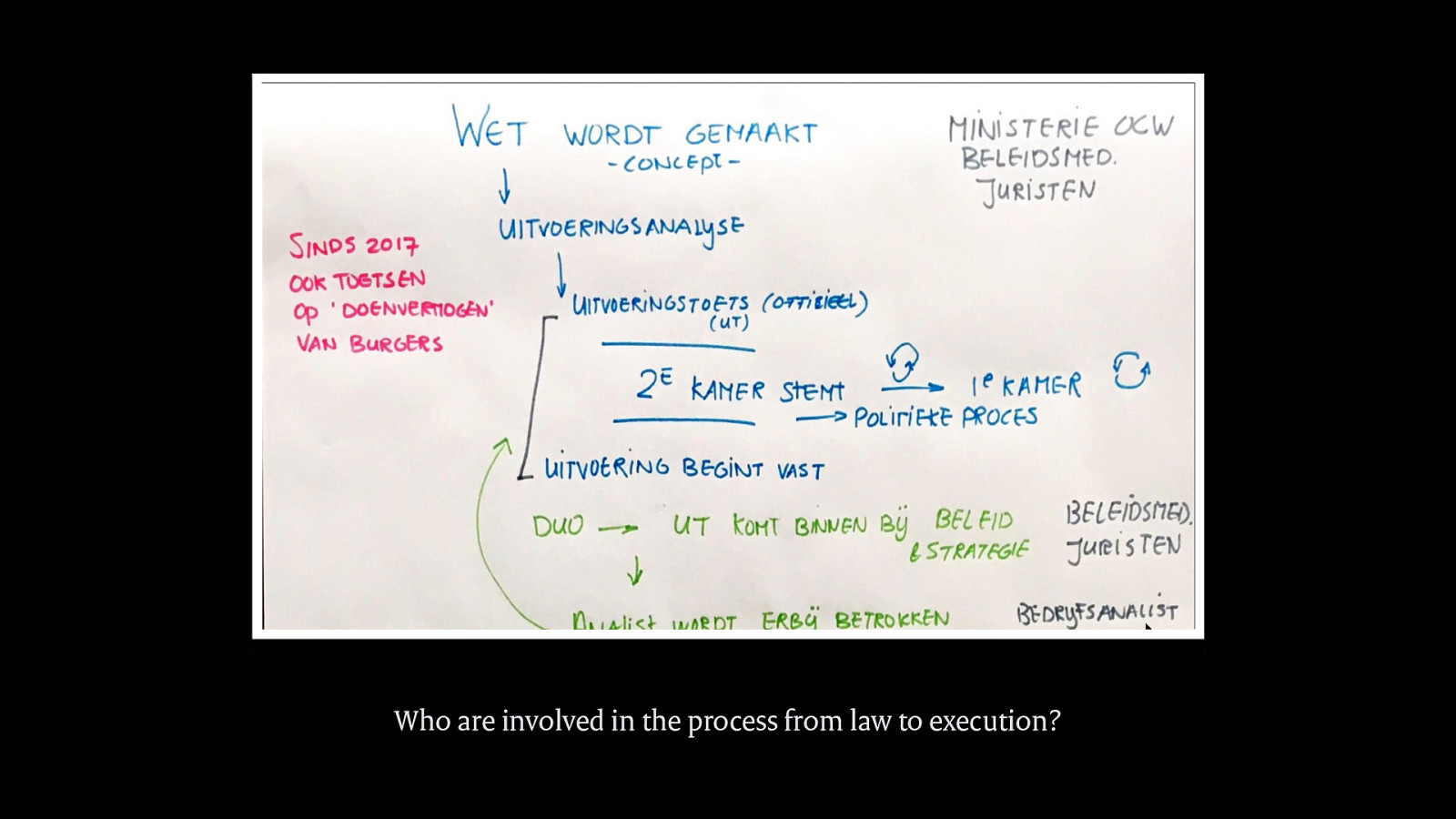

However, we never talk about this side of things. We never talk about how our humanity or world views impact our work. We are mere operational developers right? We just execute what they decided in Parliament and at the ministries right? But that’s not true. When you look at how laws are made and translated into regulation, automated decisions, forms and letters, we make decisions every step of the way. And as Marleen Stikker says ‘it matters what choices are made when we develop technology and who we are behind the drawing board’. I wanted to know how we as makers of the digital government make those decisions. Which pieces of ourselves do we put in the things that we make? And how much ‘room’ is there in that process for our users?

I started asking my colleagues if I could photograph them as a compassionate civil servant. This is how that went for example with Jean, a business analist.

(Also video only in presentation)

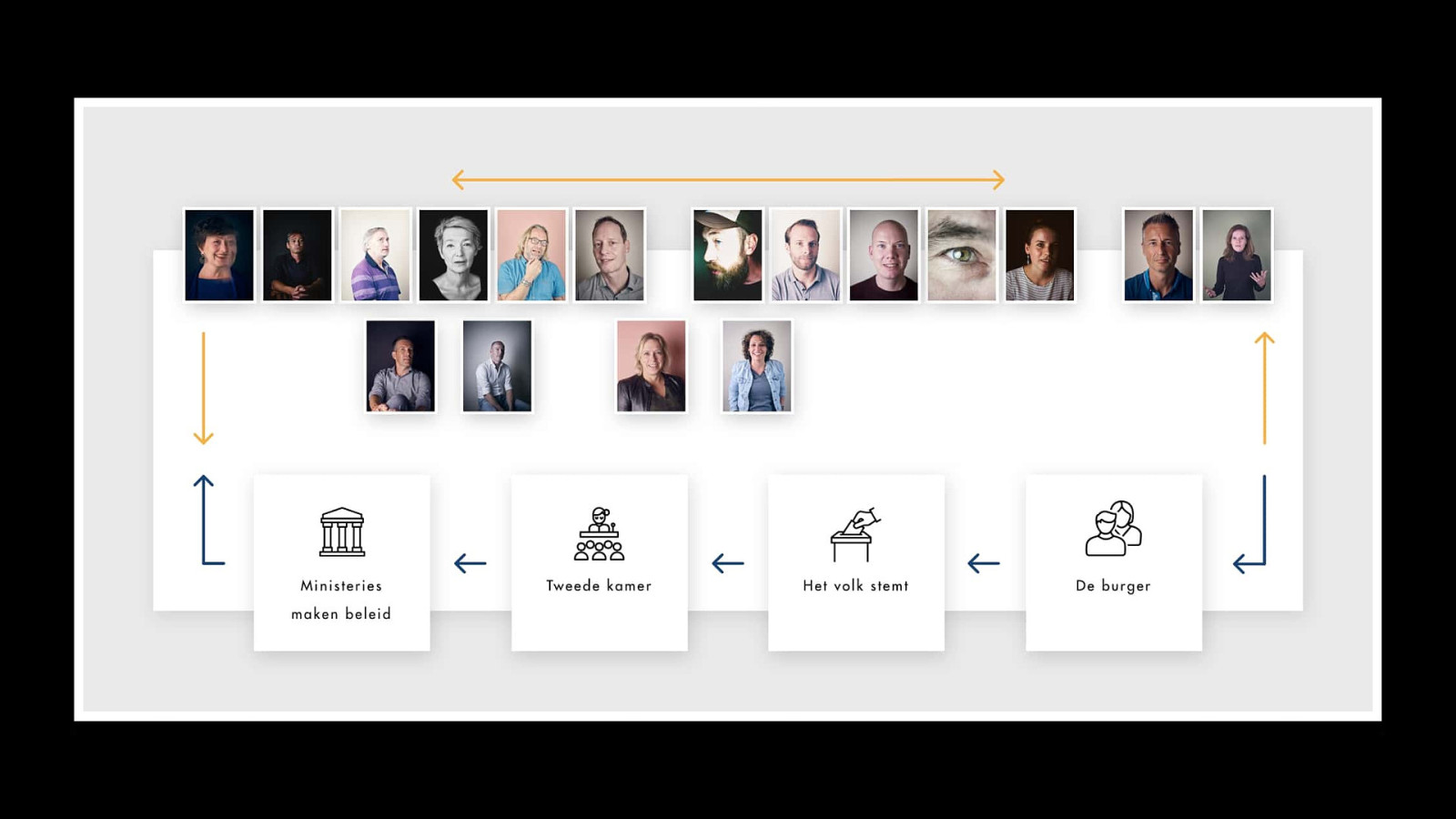

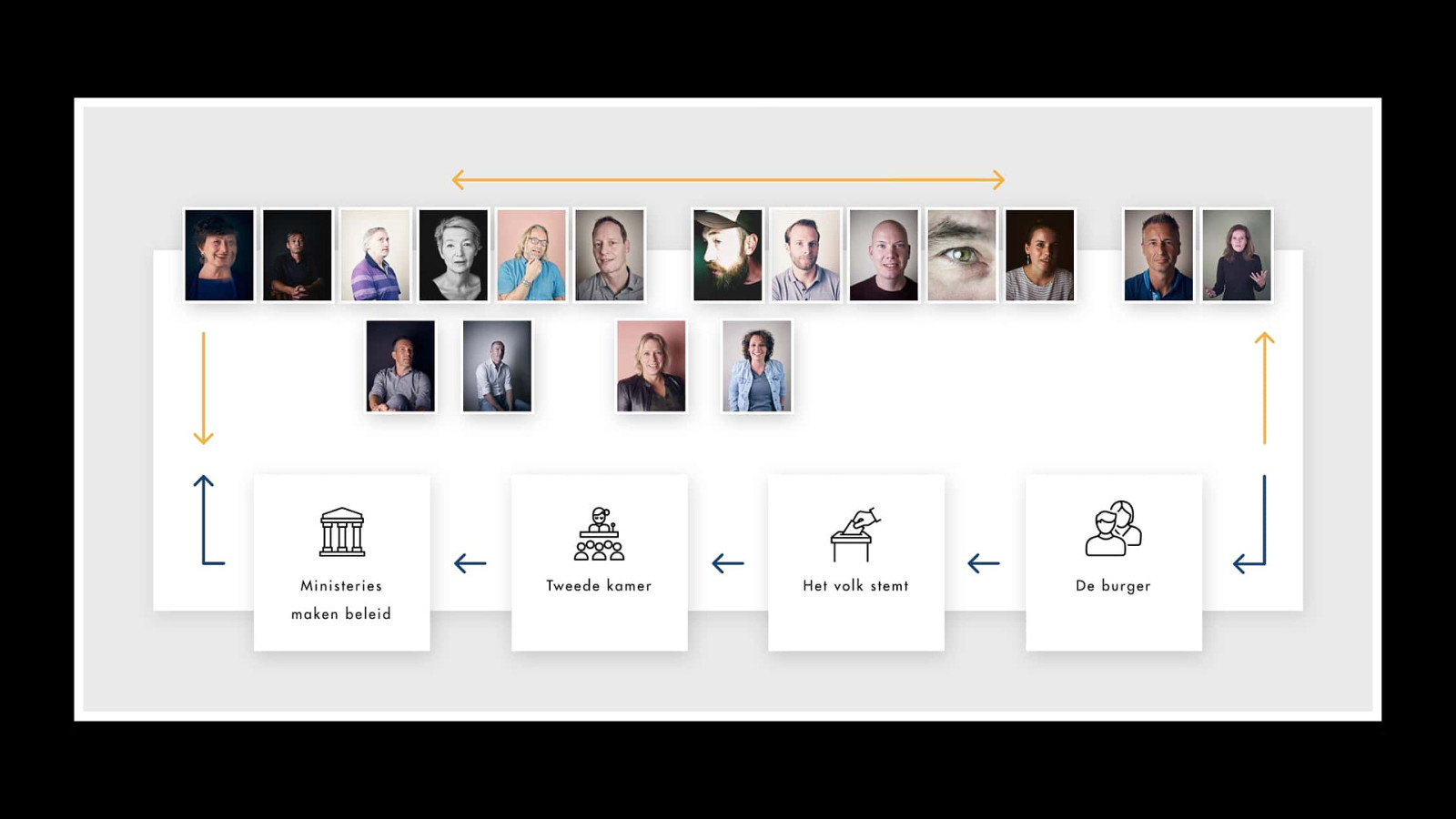

I collected more of these stories and arranged them in what I call the relay race from law to counter. Which sounds so much better in Dutch by the way: de estafette van wet naar loket. I call it this because everyone does only a small part but together we give form to this relation between citizens and government. The black arrows is the way it normally goes in government. But the yellow arrows are how I think it also should be. We need two way streets instead of the one way street we’re used to.

In every photo-interview some dark pattern emerged. It’s the reason why we can’t live up to a compassionate connection with citizens. Even though we are nice people. The dark patterns are part of ourselves, our organisation, our interaction with our political leaders and within our relation with citizens. And when we work in digital government we have to break these dark patterns. I’d like to give you a quick demo at the website I designed to present this research and to show you these dark patterns.

—> go to debegripvolleambtenaar.nl and their I free-styled through the site and explain the dark patterns. Sorry it’s not in this slide deck :). But check out the website for yourself and you will know what I talked about!

I published these essays in the summer of 2020, and right after I started working on the corona-app. I did that for five months and then in the fall I took a break for a couple weeks. I bought a rubber boat and paddled a lot. Thinking about what’s next.

There was a lot of recognition of the dark patterns within other organisations. But my essays didn’t change the world. Of course they didn’t, change is that much harder and as we heard yesterday from Jeremy Keith, people don’t like change at all. And that put me down a little bit.

In that time the child benefit scandals in the Netherlands started to appear a lot in the media. In our parliament they held hearings to investigate what exactly had happened. I listened to everyone of them and I got even more upset.

So I paddled a lot.

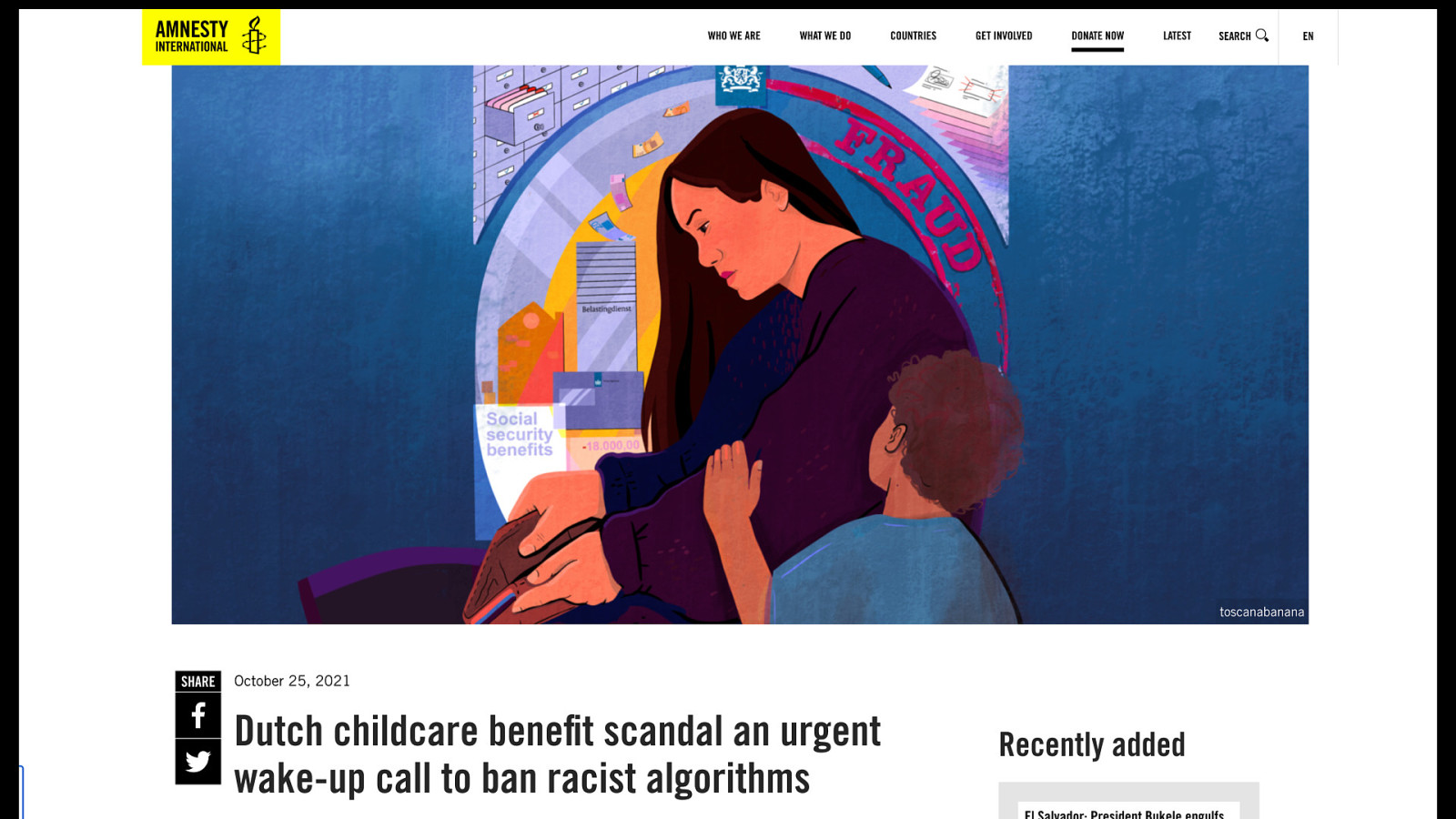

Some of you may have heard, but in short: our tax office used biased algorithms in the execution of the child care benefit. A lot of parents ended up in debt and very tough personal problems because of that. And also… the majority of the victims had a non-Dutch background and last month our cabinet finally admitted that we have institutionalised racism in our government and that tripled down in how we developed our technology.

In the beginning a lot of governmental organisations thought ‘that’s just the tax office’. This is not about us.

But it is.

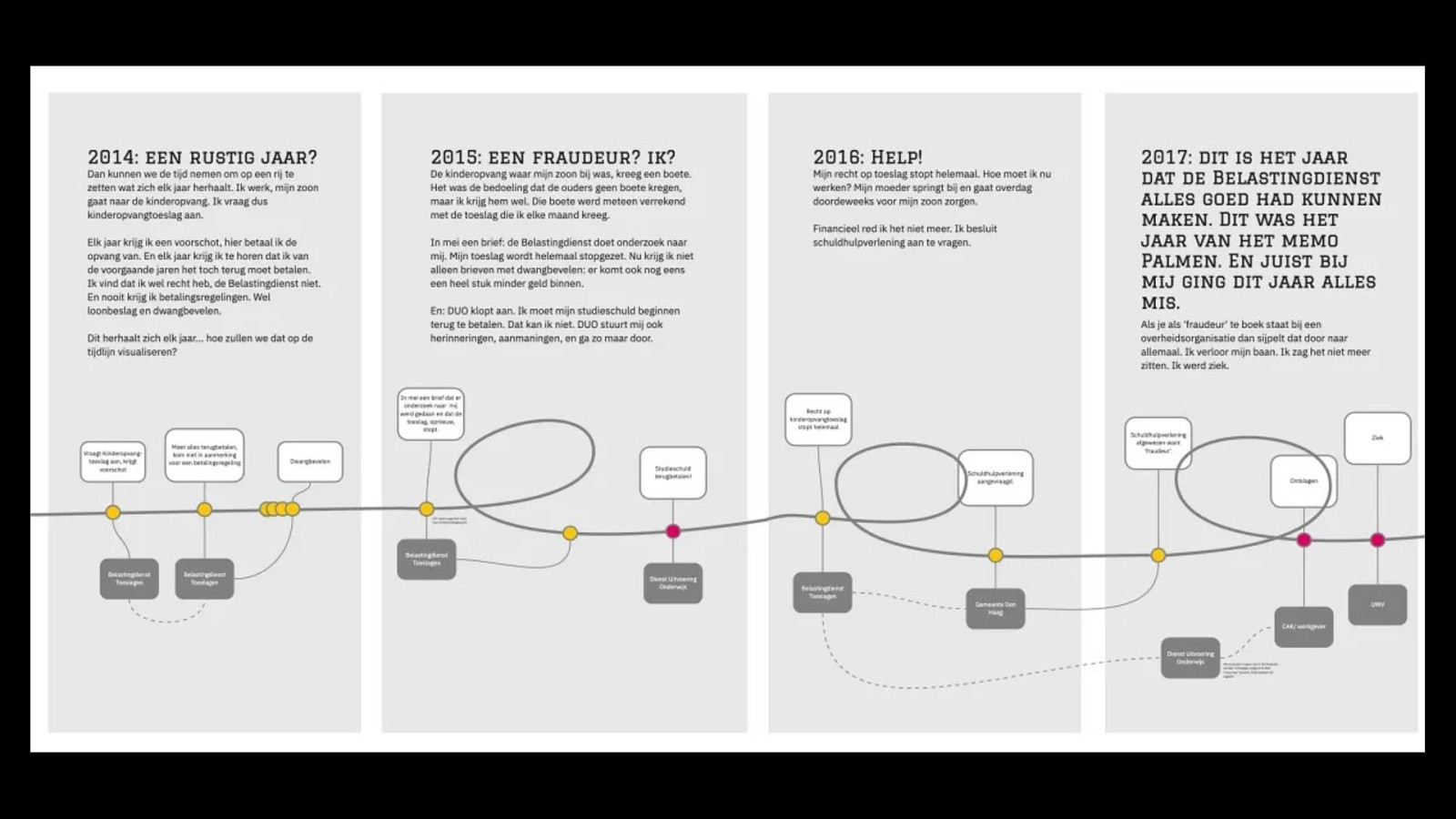

Together with one of the victims, Janet Ramesar, I made a timeline from her story. We wanted to show that it’s not ‘just’ the tax office, because when we use automated decisions we use data from other organisations and combine these. Digital government is deeply connected and it’s very hard as a citizen to know how. People like Janet did not only had problems with the tax office, she got entangled in her entire relation with government.

From Janet I learned that you never have a relation with just one organisation. Your connection with government is a complicated one and consists of multiple ‘journeys’, interactions and services.

I wanted to learn more about that so I did an experiment of my own. For a month I tracked every interaction, big or small, that I myself experienced with governmental organisations. It resulted in a big mapping.

After that I researched what organisations were behind these interactions, how they were structured and what law they executed. Lets zoom in a bit.

—> Let’s get into a bit more detail on this month of my relationship with the government. Open miro board: https://miro.com/app/board/o9J_lcpygEU=/? share_link_id=227461685642

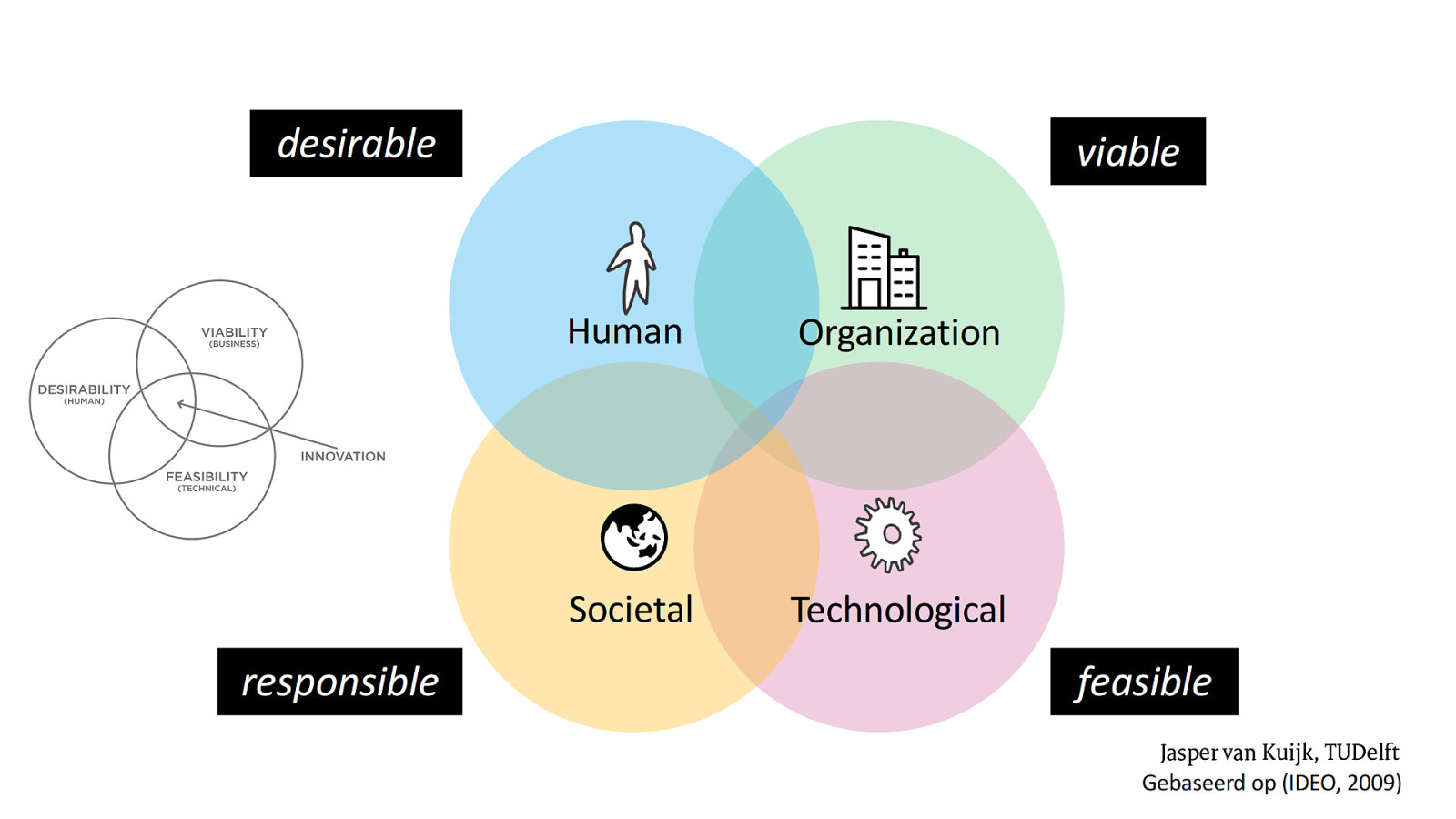

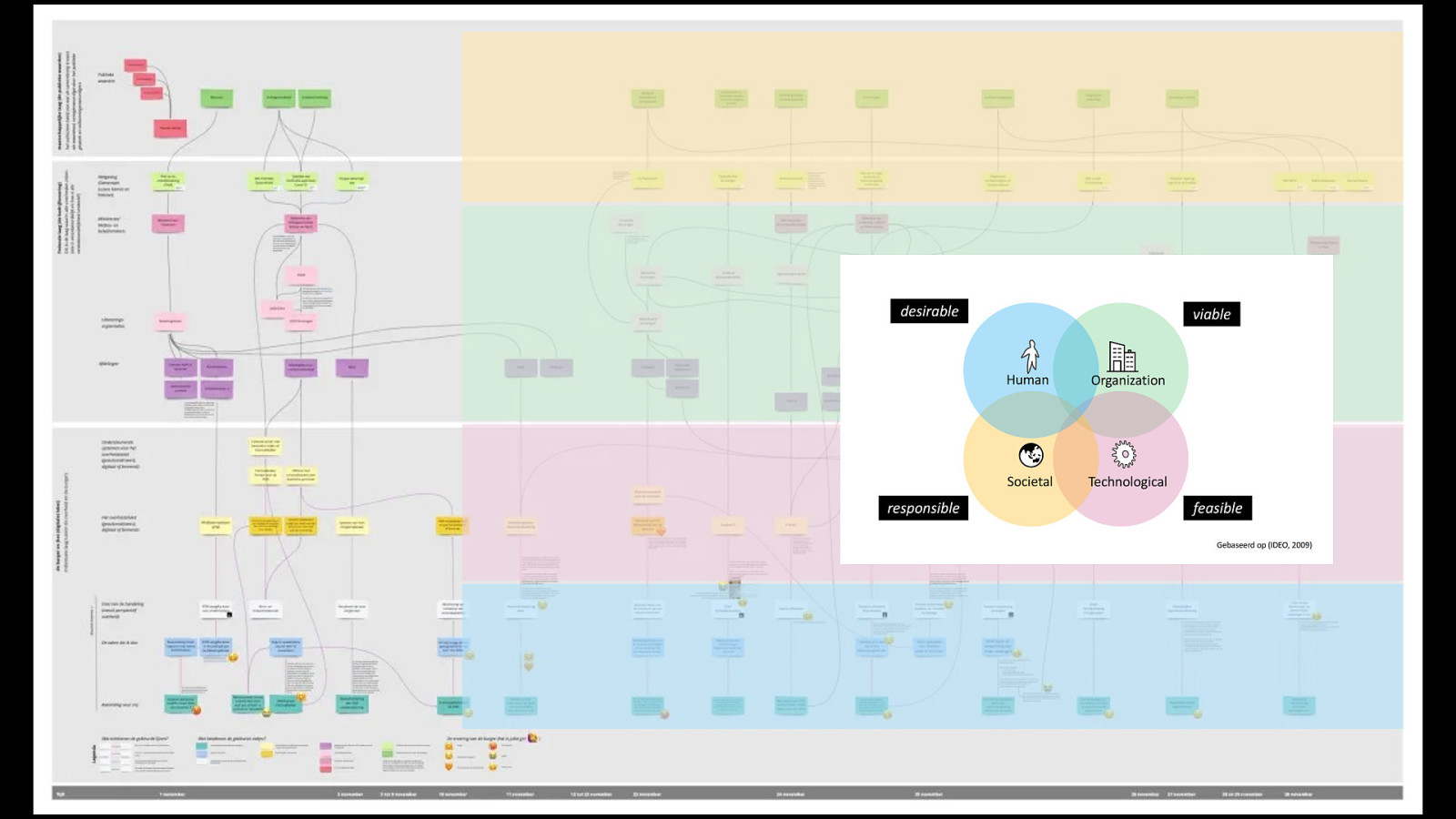

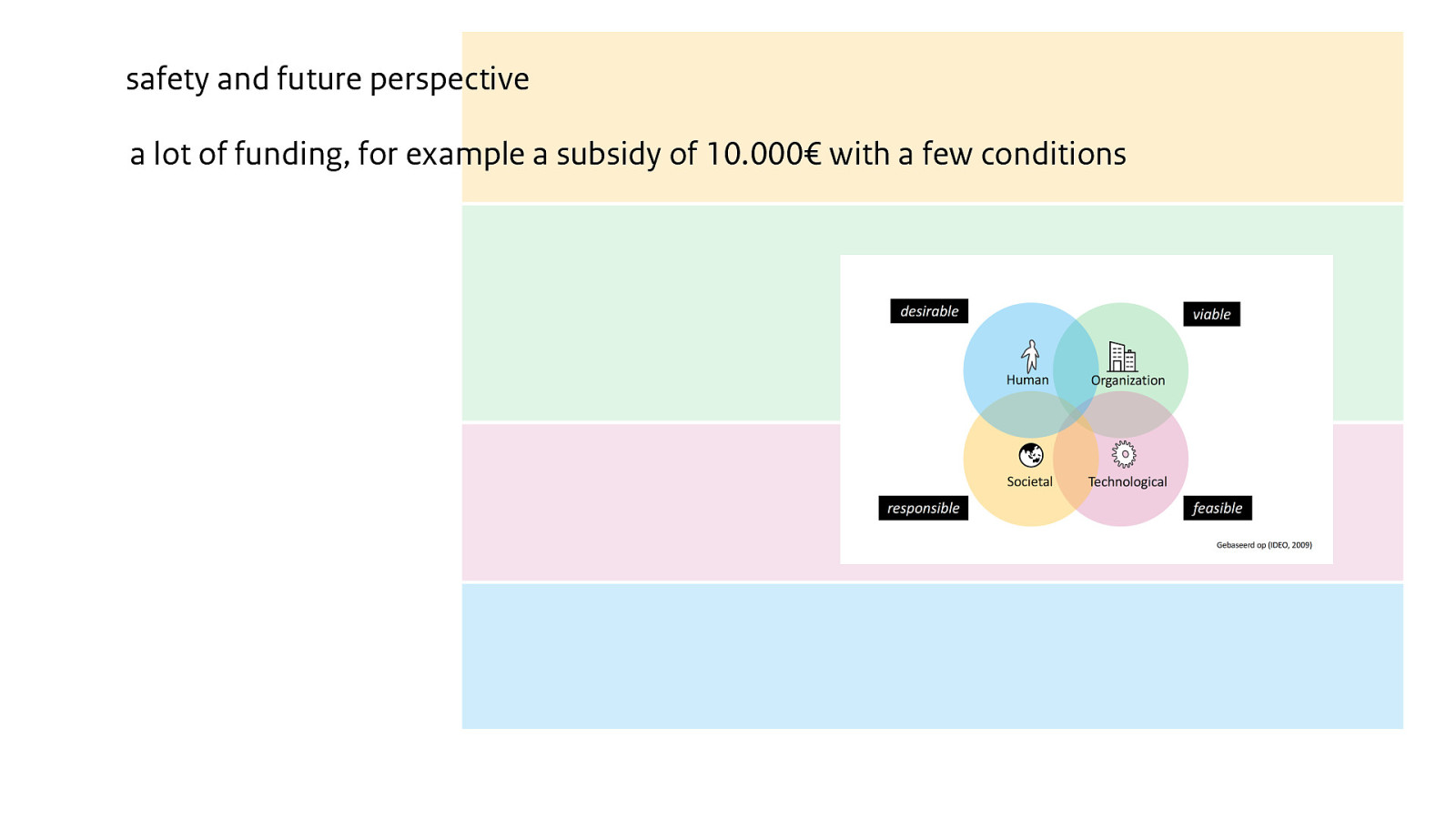

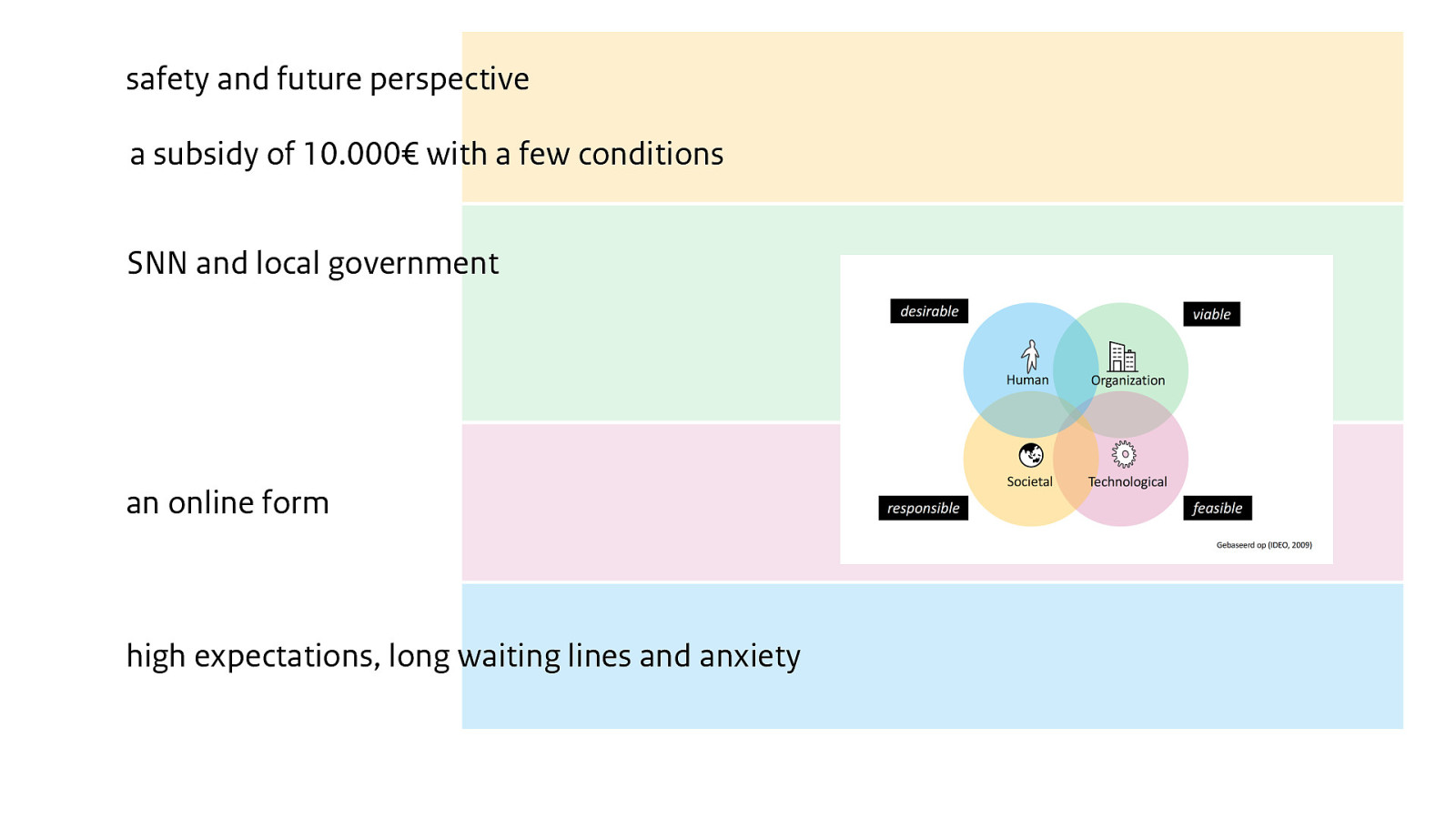

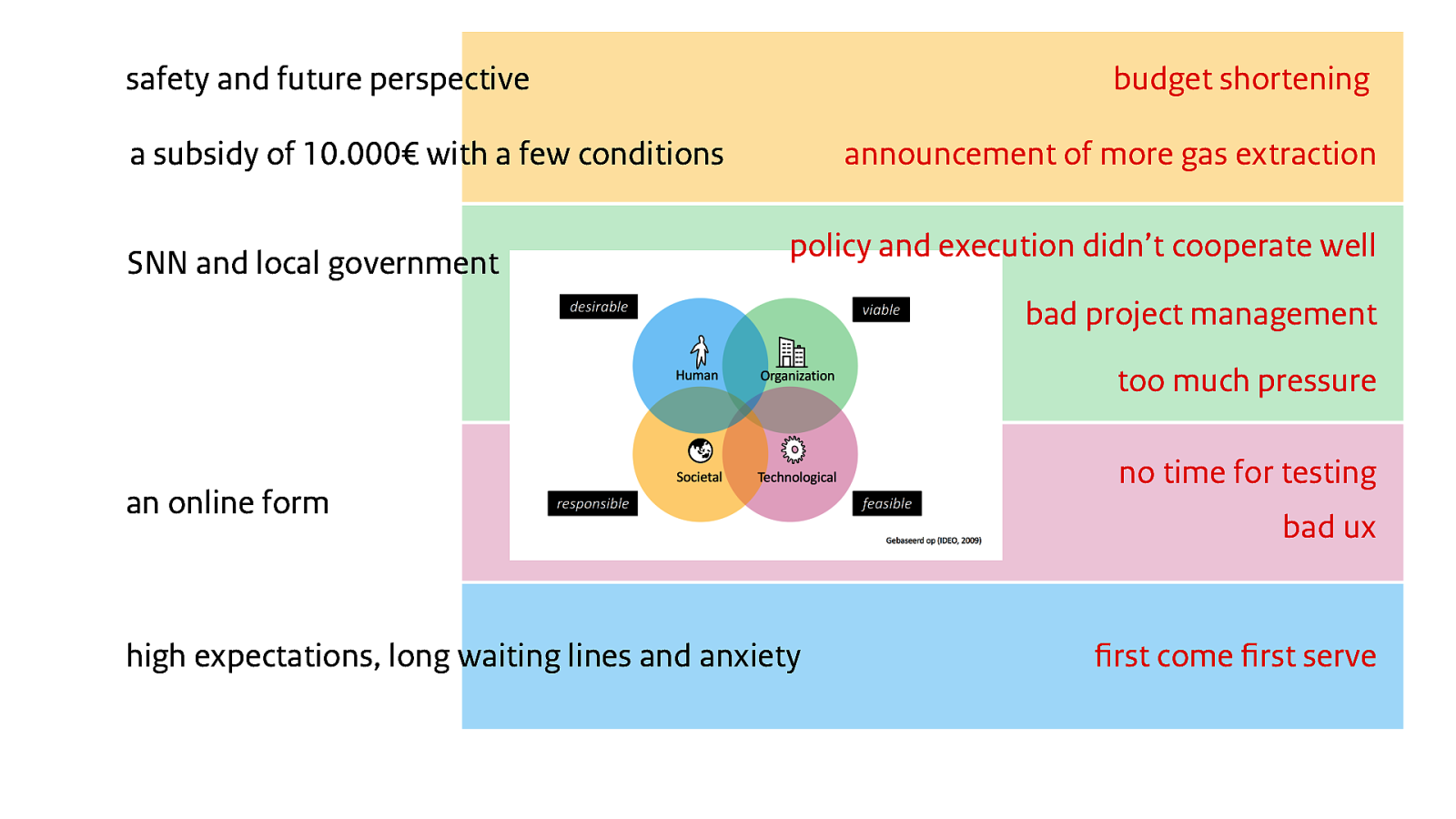

Back to the slides. IDEO uses three lenses to use as a designer. Jasper van Kuijk from the TUDelft added a fourth: the societal lens, about responsibility. Real innovation happens when all four lenses are overlapping.

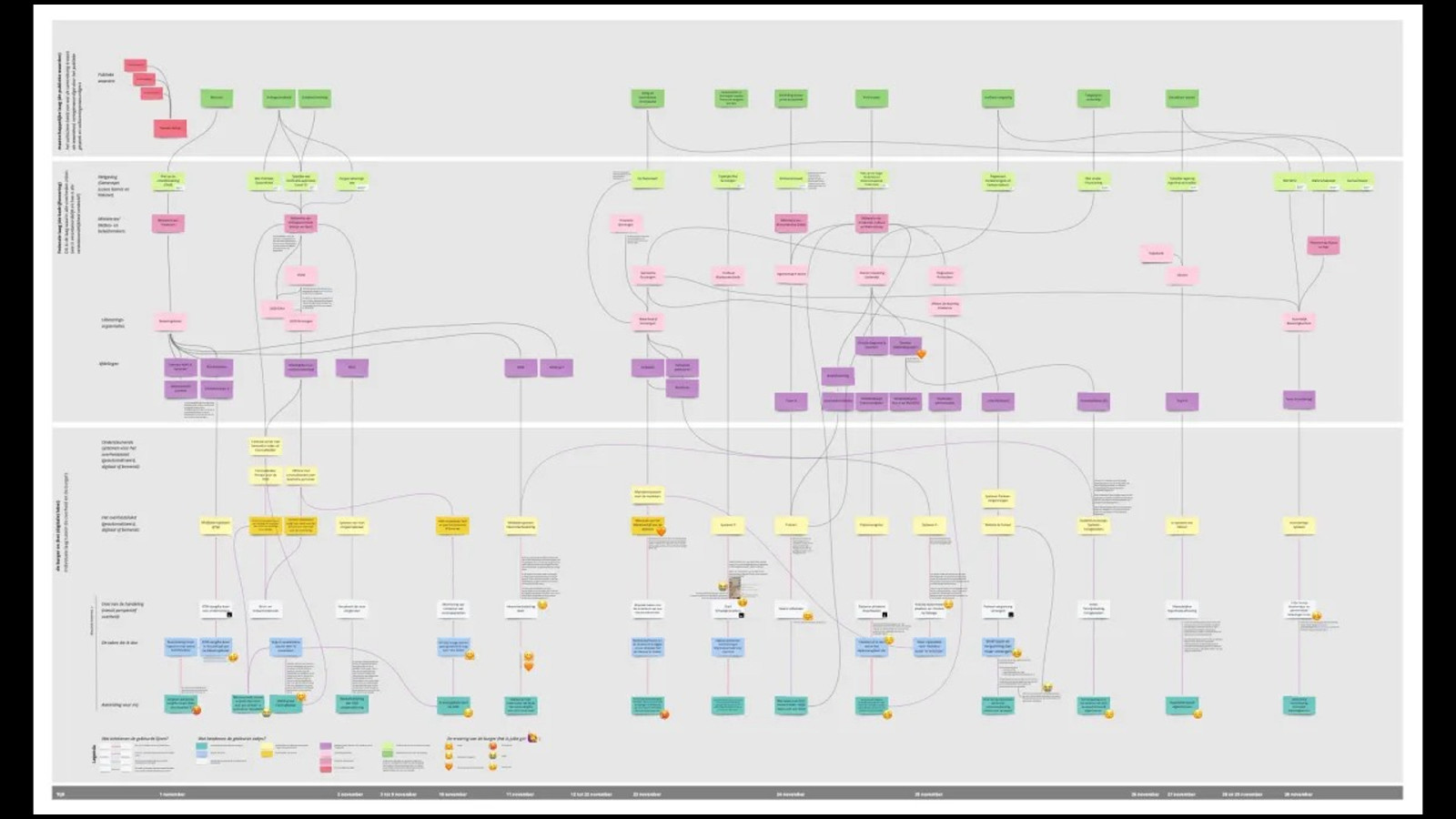

When I use those four lenses and put the layers on my mapping from the month of my relation with government, you get something like this.

We start with societal needs, we translate them in laws and regulation. Then we get the perspective of organisations and business cases. From that we start translating and building it into technical systems, and last but not least there is the interaction with users.

When we work in digital government, we are really focused on the business and technical perspective. Business cases are always leading when we make digital products of work on technical innovations. User research or usability testing is time consuming - there is no part for that in our sprints, with backlogs that our full a year ahead by the way -, we have little experience with co-creation with citizens and look to that as merely PR activities. We look at the societal values as something that should be discussed in parliament, not in our development sprint.

We love the technical side of things, you know, we make stuff. But that is naive. Because to make truly responsible human centred digital experiences, we need to look through all four lenses.

I’d like to give you an example from a research project I did last year when I worked at the National ombudsman.

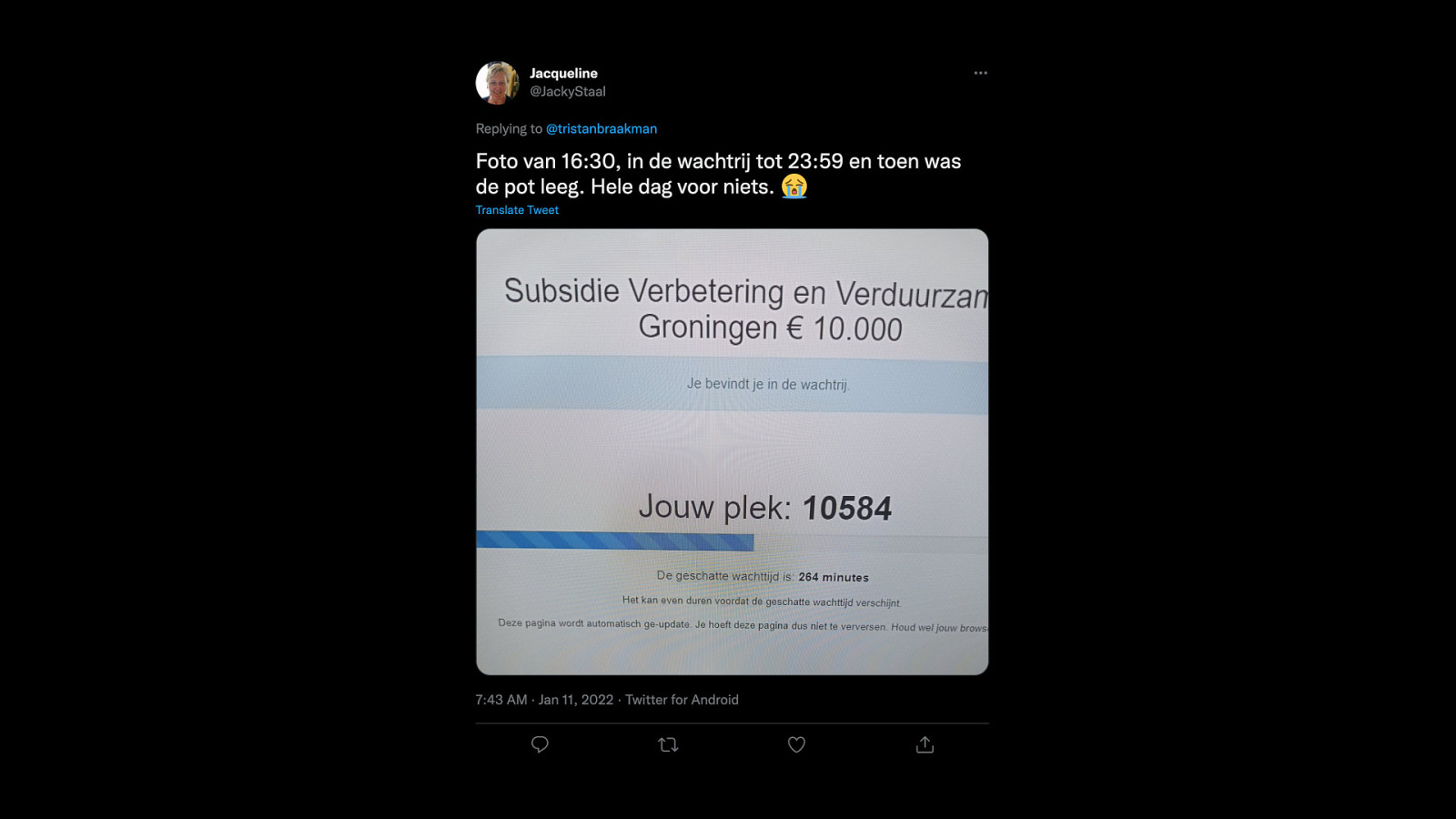

In the first days of January there were long waiting lines in Groningen. A subsidy was opened of 10.000 euros for Groningers living in the earth quake area. At every local government office there were these lines, but the online lines were even longer. People waited for more than 15 hours in an online waiting list to apply for the subsidy.

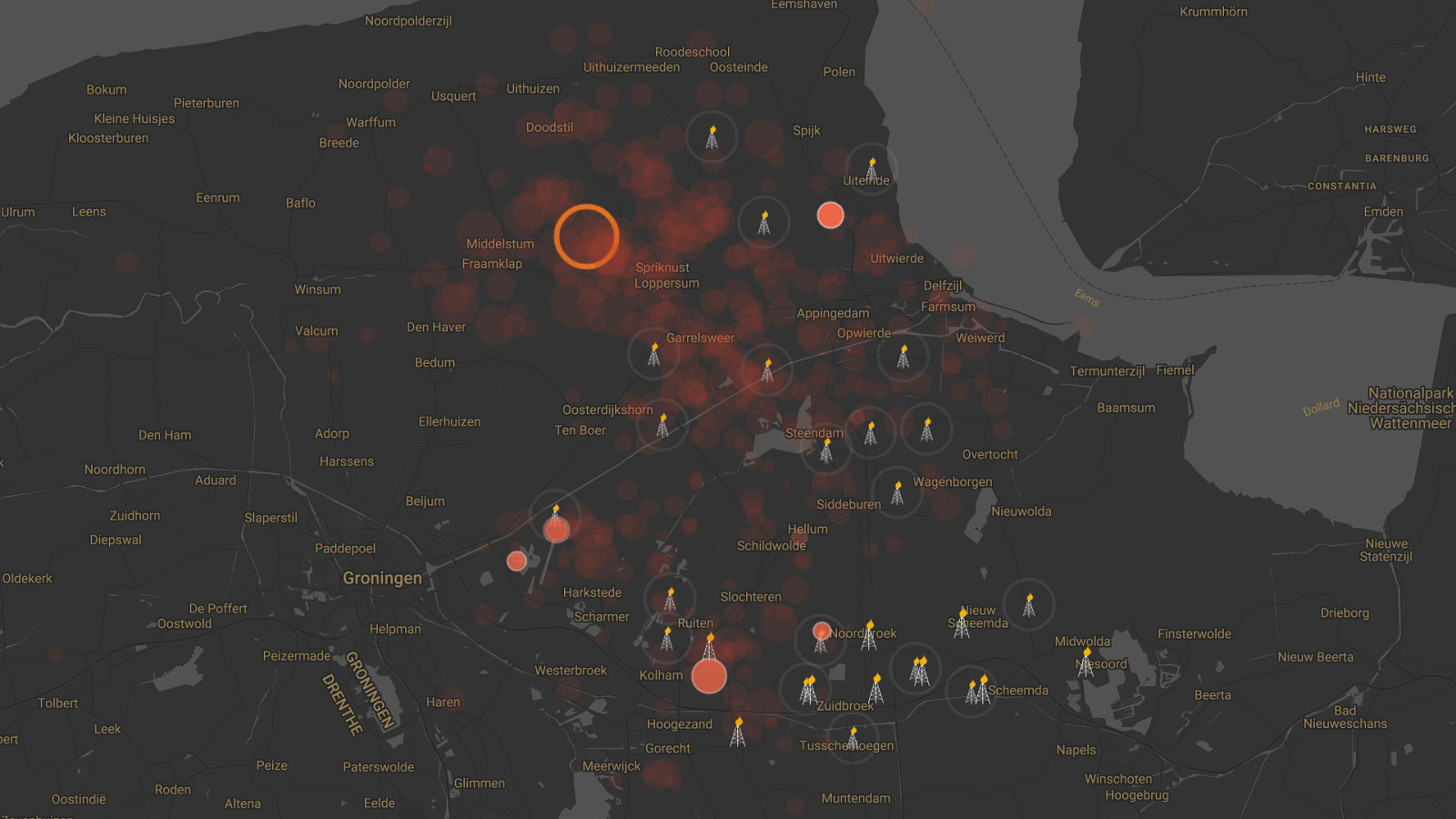

Before we dive further into the interaction with this subsidy, what am I talking about? In the North of the Nederlands there are earth quakes as a consequence of the gas extraction. We started in the early 1960’s when Shell and Exxon together with our government discovered that we have a lot of natural gas. But extracting the gas caused a lot of earth quakes, and in the last 10 years our government also acknowledged them.

Kor Dwarshuis, a Groninger himself and information designer animated how many earth quakes happened in Groningen since we started winning gas. Let’s take a look. https://dwarshuis.com/aardbevingen-groningen/visualisatie/view/?lang=en

These earth quakes leed to cracks and other damages in buildings but they also make it unsafe to live in houses that are not built for these types of movement. In 2020 the IMG (Institute for Damage from Mining in Groningen) was founded as a governmental organisation to move the recovery operation from the NAM (the gas mining organisation) to the government itself. For earth quake damage you can apply for a few different services for funding to repair the damage.

A few years earlier the NCG (National Coordinator Groningen) was founded to make houses and public buildings saver to live in. For almost 25.000 building that means they have to be rebuild or strengthen. So you can imagine that is a mayor operation for the entire province with a lot of services, most not even digital at all. This is a tweet from Nicole van Eijkern, a citizen from Groningen. They started to tear down her old house in the fall last year to build a saver construction back. Quite an emotional moment for her.

So let’s do this exercise together. When we look through the societal lens we see the need for safety and to give Groningen perspective for the future. We translated that into a lot of funding, for example the subsidy of 10.000 euros we’re talking about today. But of course that needed a few conditions, because every funding and regulation needs conditions right. Lets look through the organisational lens.

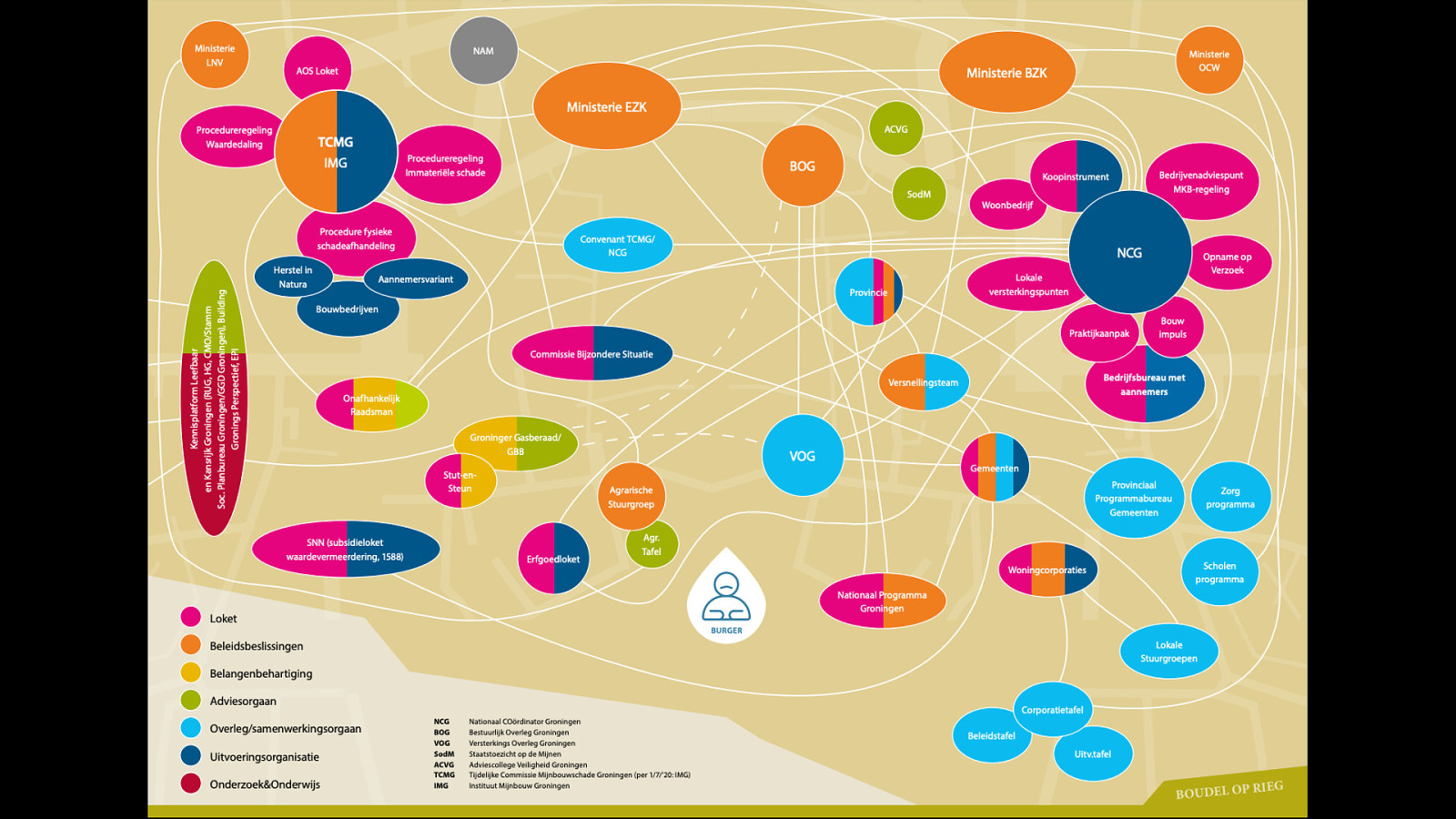

IMG and NCG are not the only organisations dealing with this topic. Groninger Gasberaad, a citizens organisation took the liberty to make this overview of all the organisations that are involved. This is an old overview because it changes a lot. The SNN for example isn’t even on this (it’s a cooperation between the province and local municipalities).

This is the organisational layer. We, the government designed this system. Of course you might say it just happened as we made changes when problems occurred. But still…

So I’m going to put the entire administrative spaghetti up there, with a special shout out to the SNN. And of course we can dive deeper into the organisational lens…

As you can imagine a recovery operation like this has quote some services, money flows, and regulations. One of these is the 10.000 euro regulation. This subsidy is for citizens who live in a specific area, who have proof of earth quake damage (and can proof that by having applied at the IMG) but who are not a part anymore for the strengthening program of their home.

A lot of these people have been unsure on what was about to happen to their homes. There was a lot of talk about safety norms. And they worried, but also doubted if it would be a waste or not to do maintenance on their houses. They postponed necessary jobs to be done.

This subsidy was an agreement between the province, local governments and the involved ministries. When executing this arrangement organisations didn’t hold in account that EVERY Groningen who complied to the conditions would apply.

But they did. And all over our province these long waiting lines happened. Almost twice as many people applied for the subsidy then there was money for.

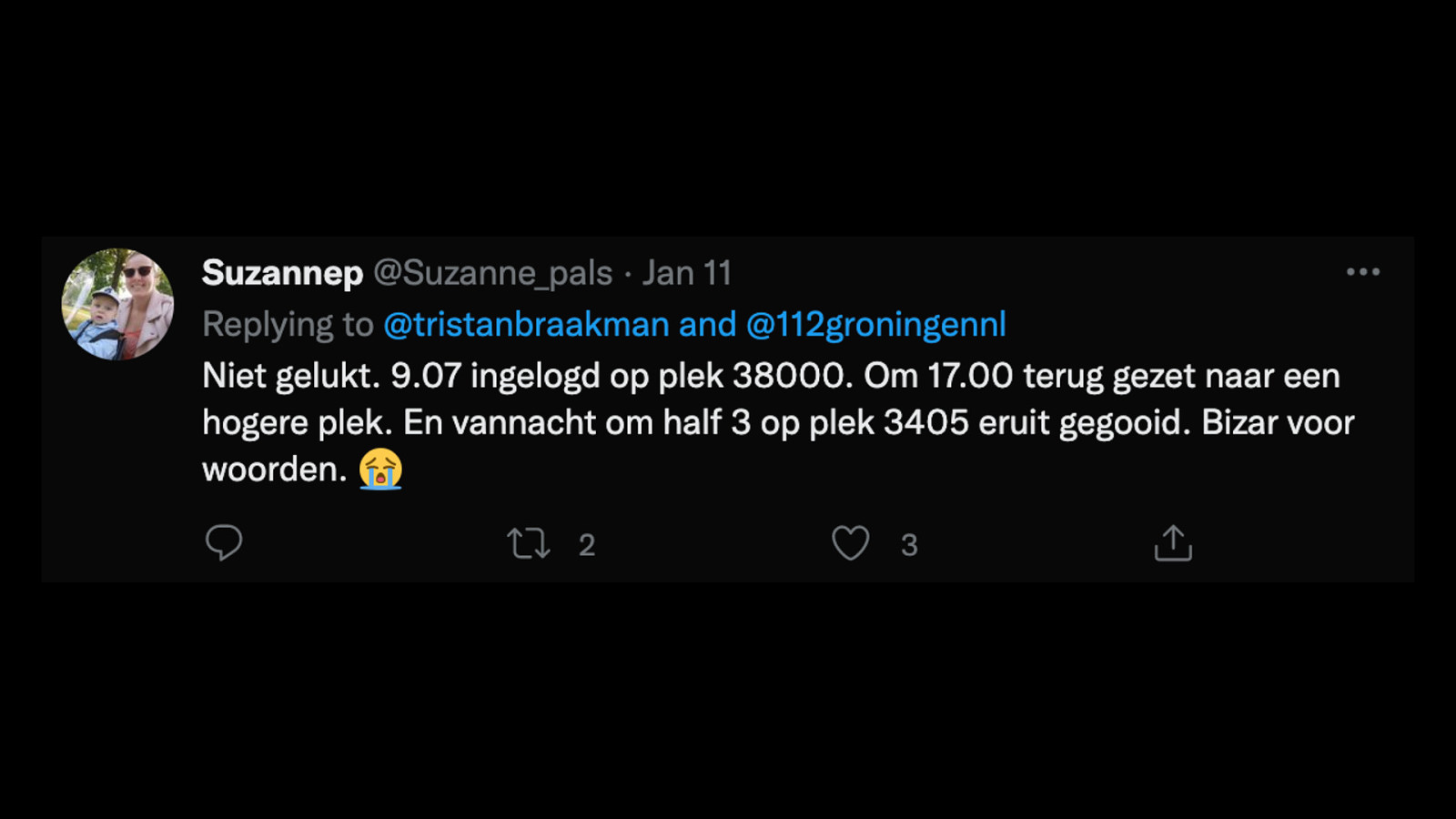

And most of them applied online, sometimes via 2 or 3 devices just to make the cut. Staring the entire day at a screen like this.

Soon people found out that when someone shared their screen on twitter with a visible url you could steel their spot in the waiting line and jump forward. And then smart people figured out, you didn’t even have to see someone else’s screen you could just change the url and jump forward or backward in the waiting line.

And of course that led to these kind of experiences.

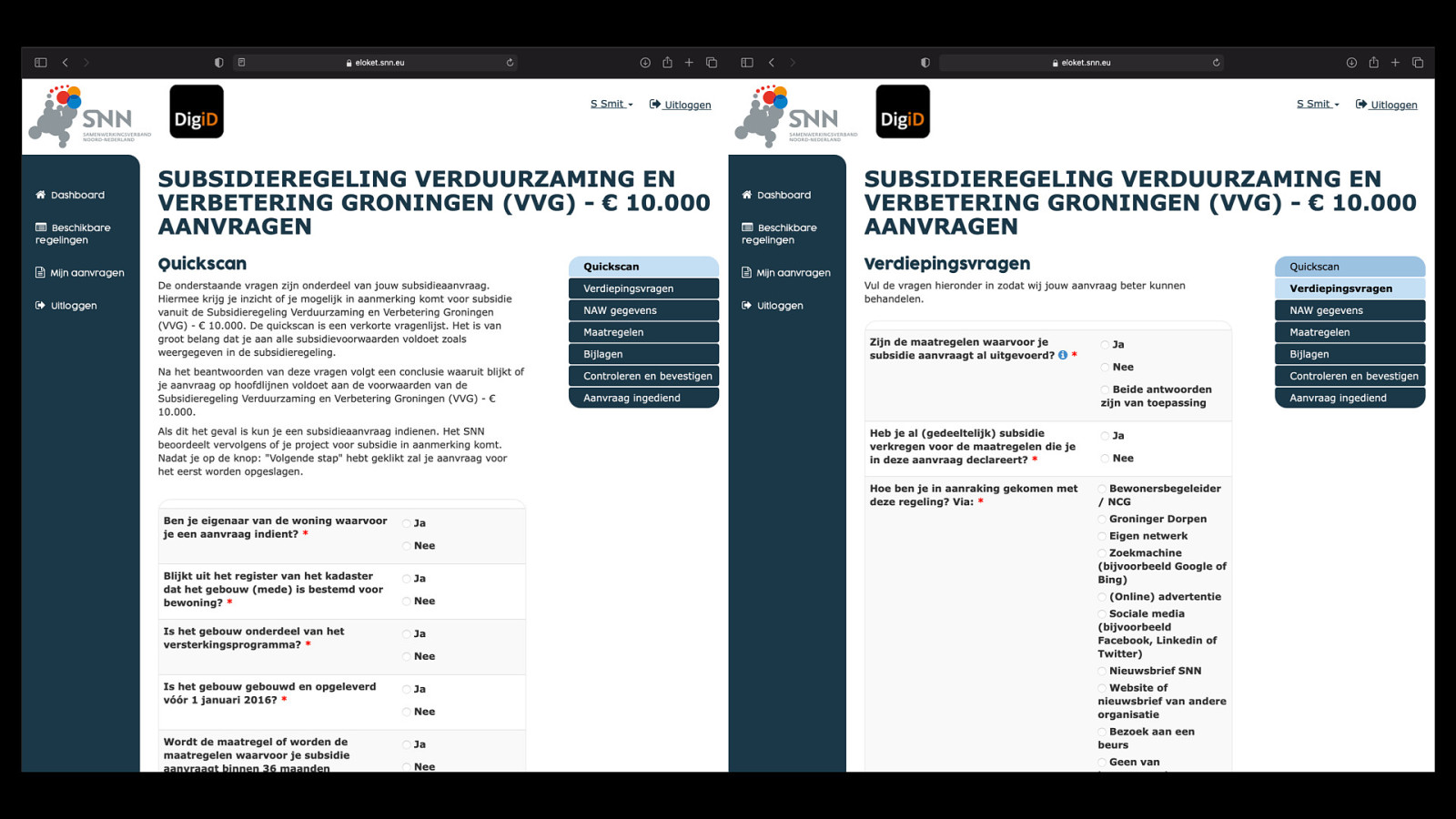

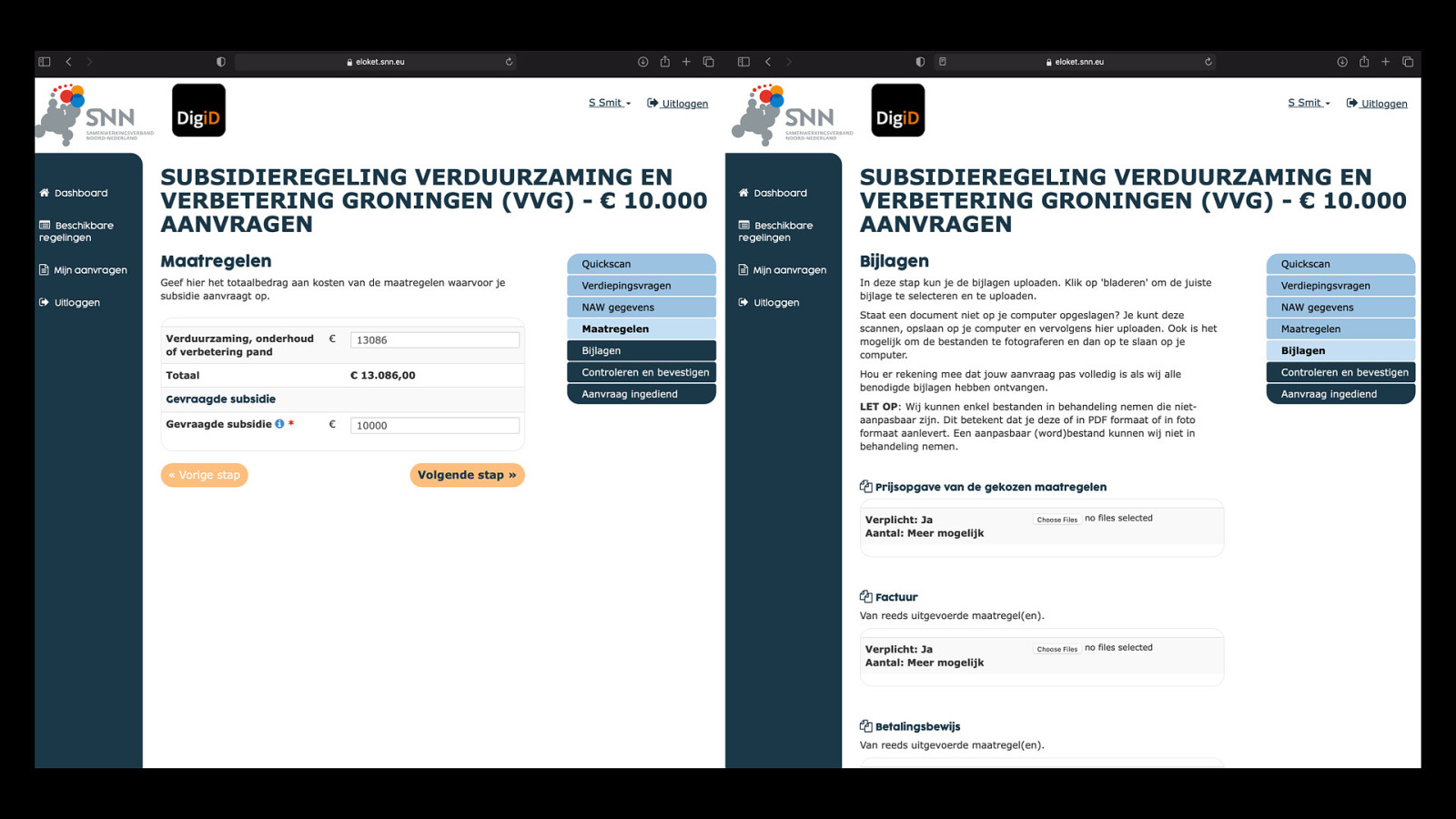

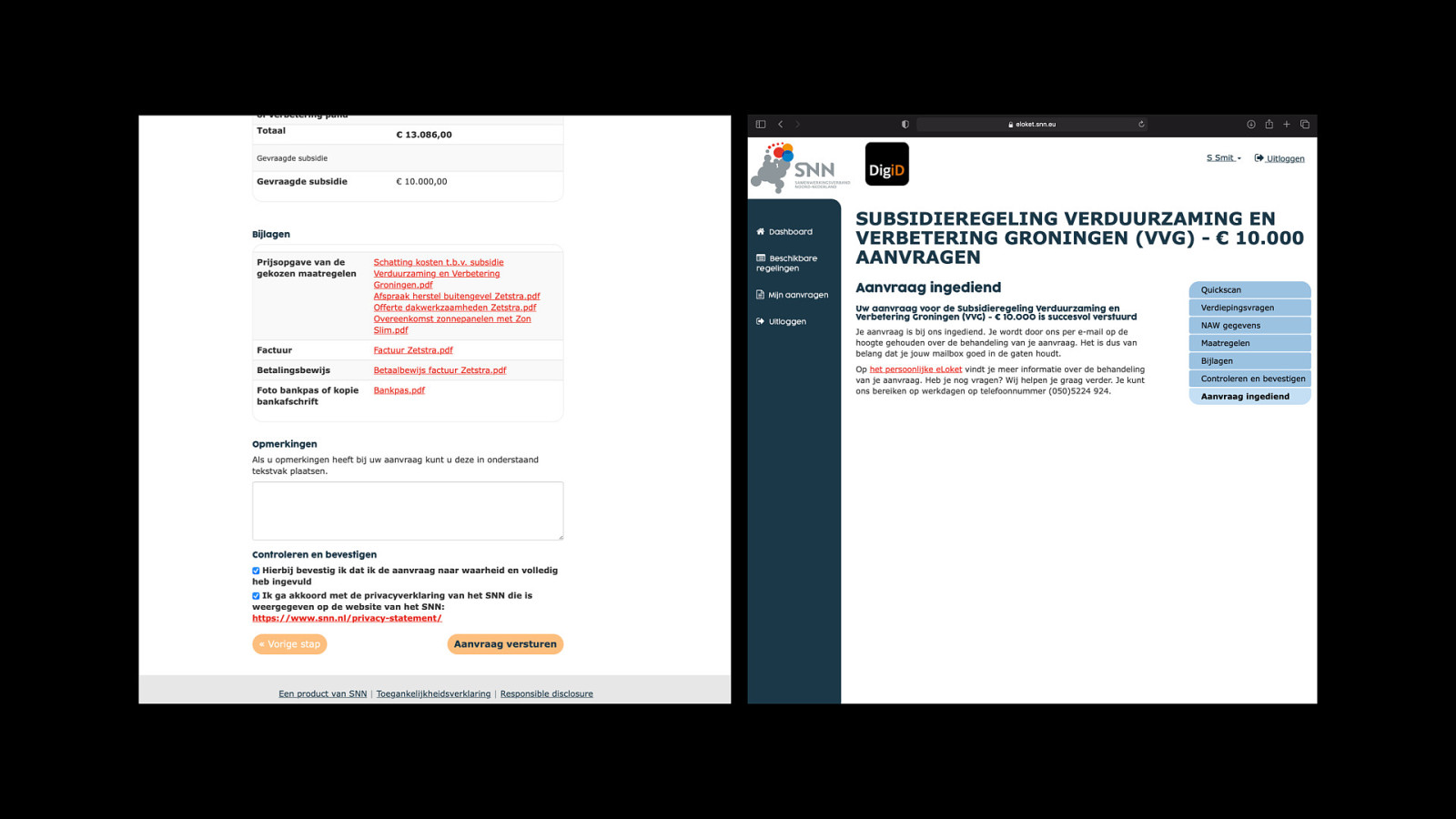

When they did make the waiting line and arrived at the actual form to apply for the subsidie, this is what they encountered.

Let’s walk through this form together. First we start with a quick scan. Some questions about your house, if you’re the owner. If you applied for a subsidy before. Etcetera.

Than there are some in-depth questions. Which are actually the same type of questions as the quick scan but never mind.

Okay… time to start with the application and fill in our personal information.

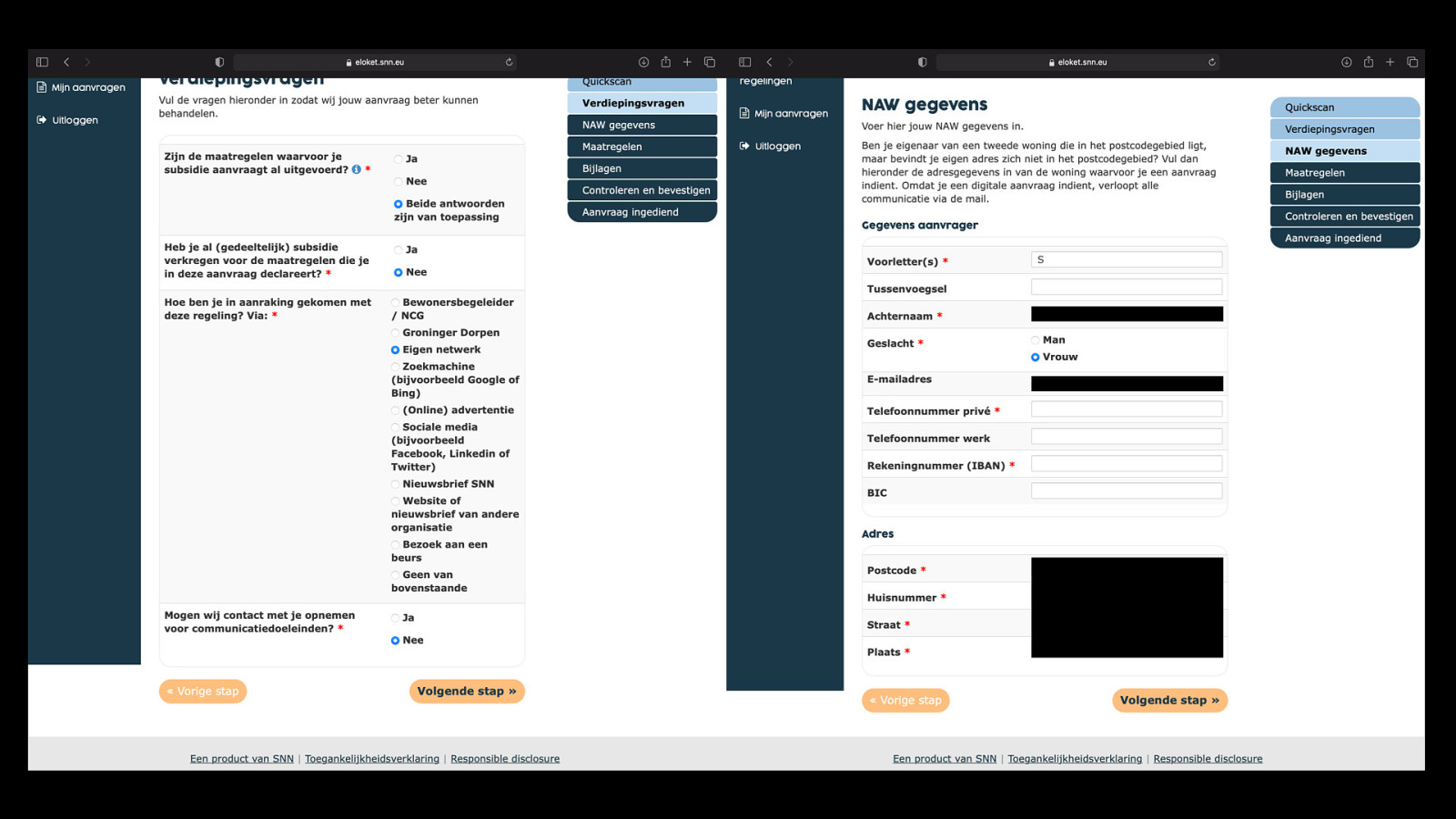

After that they want to know about the costs of measures that we took. Check. And than we arrived at the uploading of the attachments.

Also notice the ‘verplicht: ja’ fields. What if we don’t put an attachment there can we still send the application and will it later be rejected? And what if I make an error? It’s so unclear. Surely we can do better with these required fields.

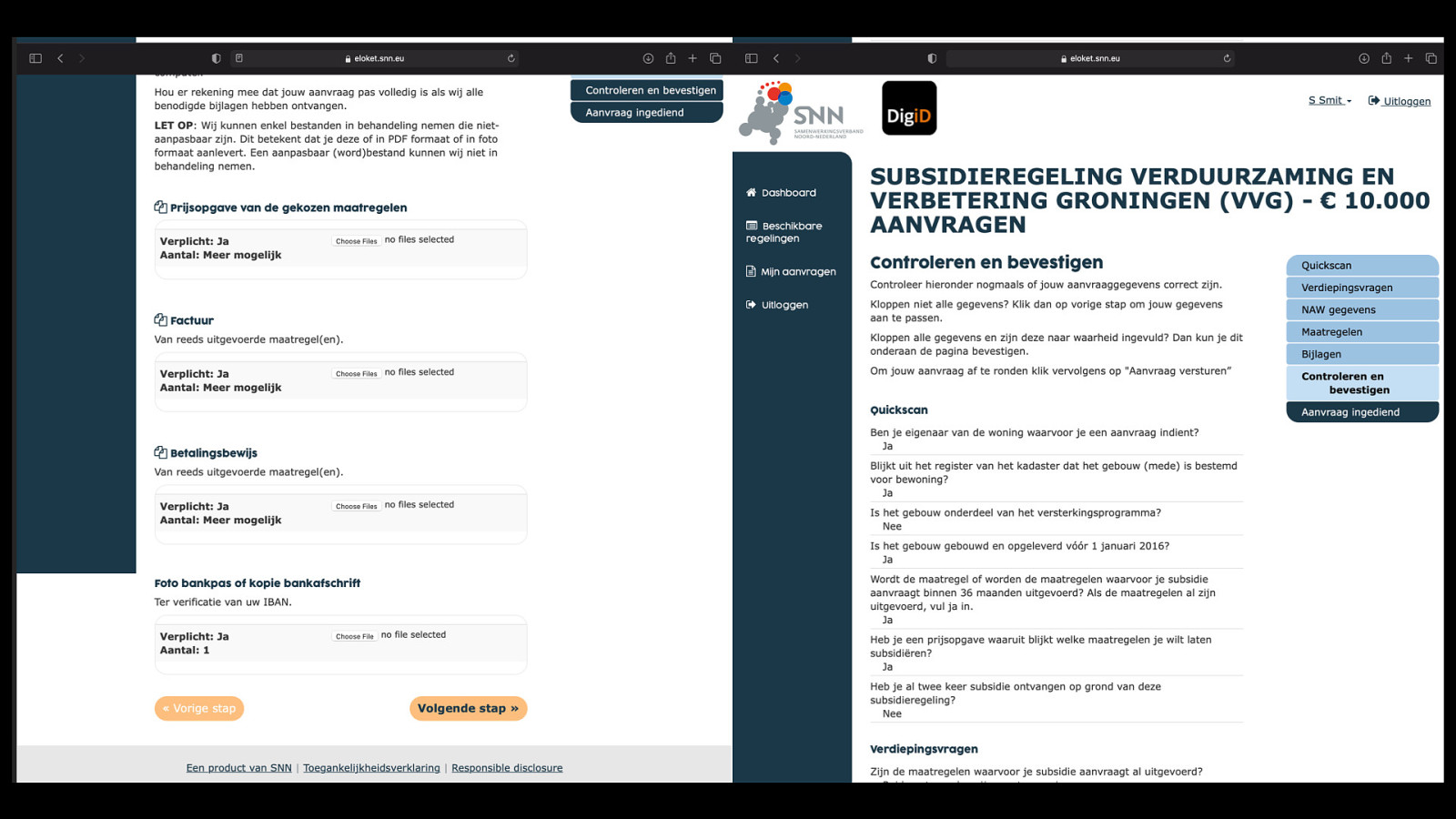

So last page on the right. Just checking everything…

Scroll, still checking everything. Send. I applied.

One of my friends sent me these screenshots from her application. She is a UX designer herself. She said that even as comfortable she is with digital applications she was very stressed. Because what if she did something wrong and after ten hours of waiting she was back at the start? It was now or never!

As you can see you have to read carefully, give a lot of information, answer some questions and attach the right documents. Sometimes she was confused what was the right answer, or what a button would do if she clicked on it, and maybe had to start over again - oh no she couldn’t because of the waiting line. And she already waited ten hours by the time she got to fill in this form.

I think it’s fair to say that the user experience of this form is very bad. And I’m not even going to talk about the styling because you’re way better experts than me. But if you want I’ll give you a minute to breath and find some peace within yourselves to cope.

And Suus, my friend is very digital savvy, but this man on twitter had a problem with his files. They were too large but how could he make them smaller? These were the invoices he got from his contractor and without them he couldn’t apply for the subsidy.

And of course… by the end of the day the subsidy jar was empty. So they closed the application somewhat after midnight. And people who waited all day behind their computer got very angry and disappointed.

Back to the four lenses. I’m going to be brief and civil, and leave it like that.

Ok, maybe not, because that’s not all.

It was such a bad user experience some thought to benefit from the situation. When governmental services fail this happens more than you think. People see a ‘business opportunity’ to be a middle man and ‘help out’ others to interact with the government.

We can say these people are evil and scammers, but if governmental services weren’t so complicated or just plain bad in the first place, there wouldn’t be room for these practises.

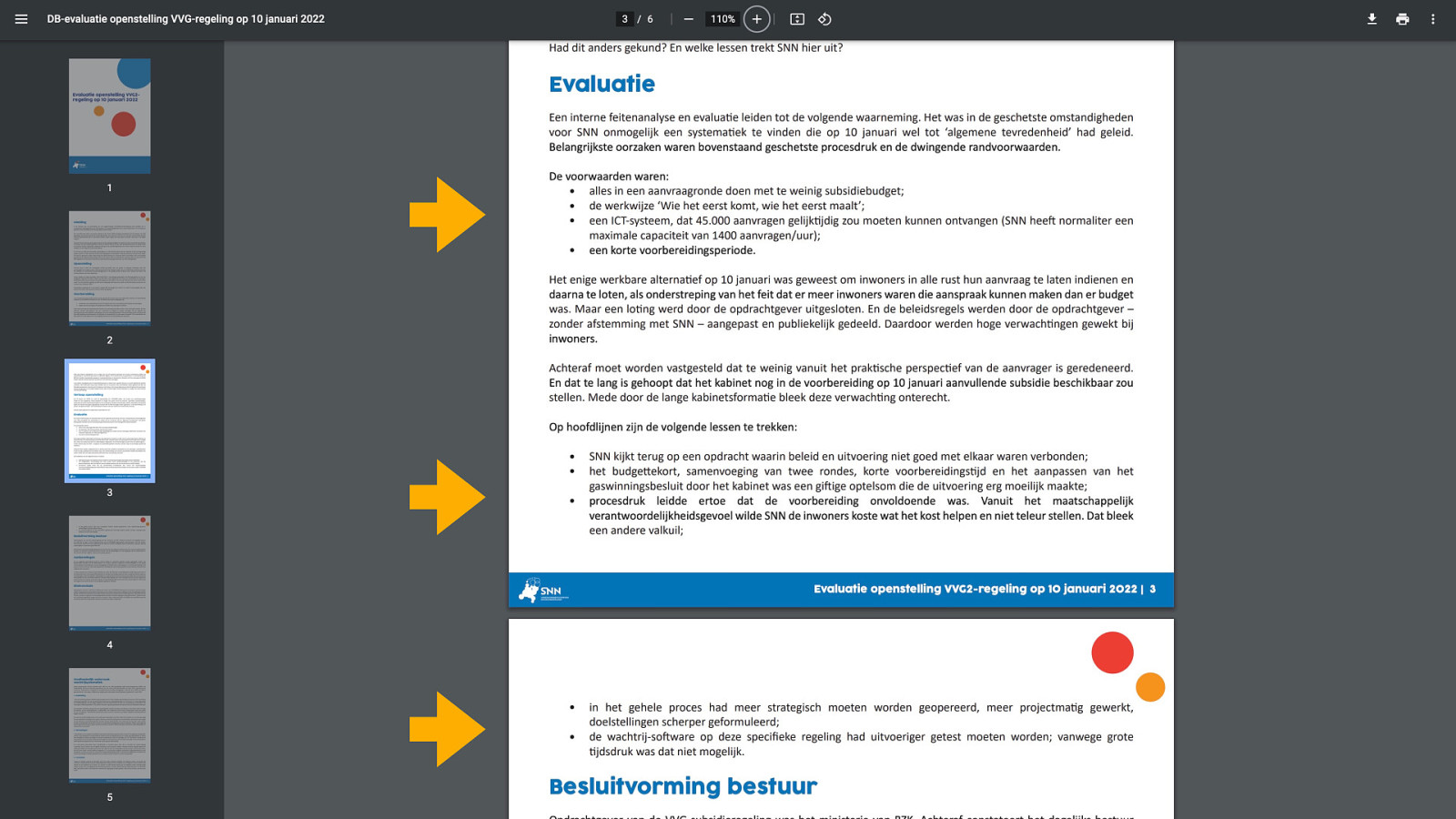

In the evaluation of the SNN themselves they point out that the causes were that there was not enough budget, the method ‘first come first served’ didn’t work out, the IT-system had not enough capacity and they did not have enough time for all the preparations.

What did they learn from this? Policy and execution were not good enough connected. The budget shortening, the combining of two application rounds, the short time for preparation and the announcement in December to extract more gas the next year turned everything into a toxic cocktail. There was too much pressure on everyone to succeed which lead to an unsuccessful preparation - I don’t get that one actually, but I can imagine that everyone working at SNN felt the pressure and that it was hard for them on a personal level.

Also: they should have been operating more strategically, manage their projects better and should have formulated better what they wanted to achieve in the first place. Also: they didn’t have enough time to test their software.

Auch.

One more time but then realistic. We might need a drink. In X minutes :)

These are the dark patterns of government I told you about earlier. We don’t know enough about how citizens experience the government. The added stress that comes with a simple thing like an online form. I won’t believe it if someone told me they tested that form on usability. I get really angry about these things because it’s so easy to test a simple form with even handful of users. It’s not rocket science!!

We don’t actually know where responsibility lies: with us or with citizens? We don’t work with citizens enough to understand that and to talk about that with them. We leave these hard discussion to our parliament but in politics they don’t test, they talk.

We don’t man up enough. Civil servants, and I can imagine the same goes for civil servants working in the organisations who deal with earth quake damage, they try their best but that’s not enough. We need more moral leadership and change our behaviours.

There is almost no one who still has a good overview of everything that happens in the ‘Earth Quake Damage Industry’. I mean it turned into a branche itself. ‘I work in retail, oh, I work in the EQDI, the earth quake damage industry’.

And lastly… we’re too afraid to speak up because it gets political. And we’re not working in politics right? We just execute what ‘The Hague’ is telling us to do.

Remember… we can’t say that ‘they’ are more important than the ministry… But why not? We should say that they are more important because they are.

Mike Monteiro writes in his book Ruined by design that the world is exactly how we designed it. It’s fucked. He calls designers gatekeepers. They are responsible for the gate of what’s getting out there.

In government I think we designers and developers are the closest to the connection to citizens through our digital products. We are the gatekeepers. So we have a responsibility. We’re not designing or building a form. We are building a perverse waiting line.

When working in digital government we should always be aware: we’re making the line, the yellow rope, the connection. And we’re the gatekeepers of that. And that means that we have to get to know the other, work together, show moral leadership, zoom out and get the whole picture and also… don’t mind if gets political. But speak up and show responsibility.

Because when you work as a designer or a developer, you work in politics. And we should take that much more seriously.

Thank you very much, and if you’re having some questions I’d be very happy to answer them.