Hi and welcome everyone at my interactive session at UX Insight 2020. We will discuss how to turn your personal art form into a research method that you can use at work.

A presentation at UX Insight 2020 in September 2020 in by Maike Klip

Hi and welcome everyone at my interactive session at UX Insight 2020. We will discuss how to turn your personal art form into a research method that you can use at work.

My name is Maike Klip. Here you find my contact information.

What are we going to do for the next hour and a half?

I am going to explain some theory about design research, what it is and how you can design your own research method. I will show the work of other design research as my own work to show how others have been doing this type of research. And I have prepared some small exercises to help you design your own research method.

Of course there will be enough time for questions and sharing what you’re thinking. At the end of this session you’ll be able to conduct your first artistic research iteration.

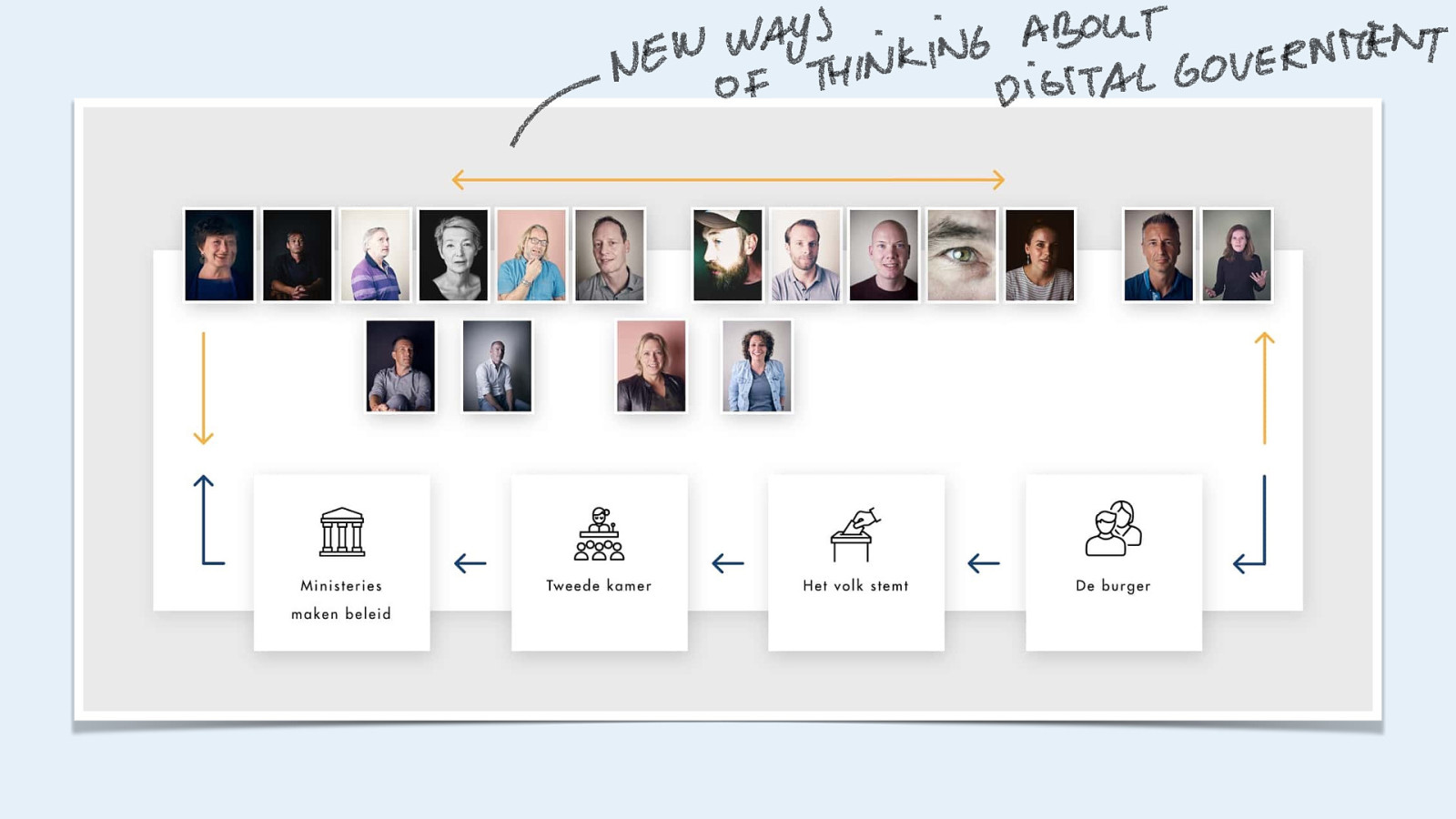

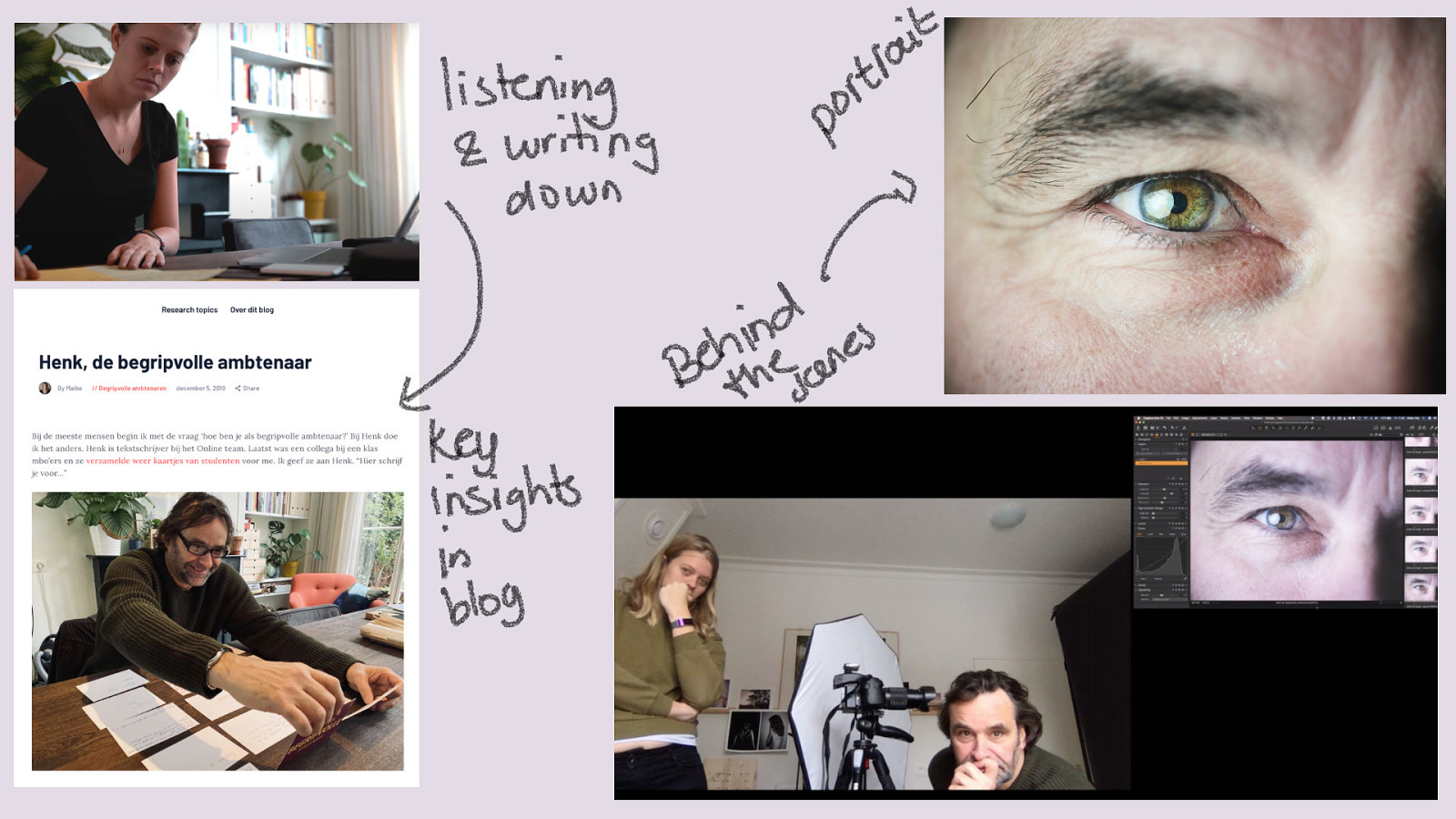

I’m going to start with a short introduction of my own design research project that I have been doing for the past two year as a design researcher for the Dutch government.

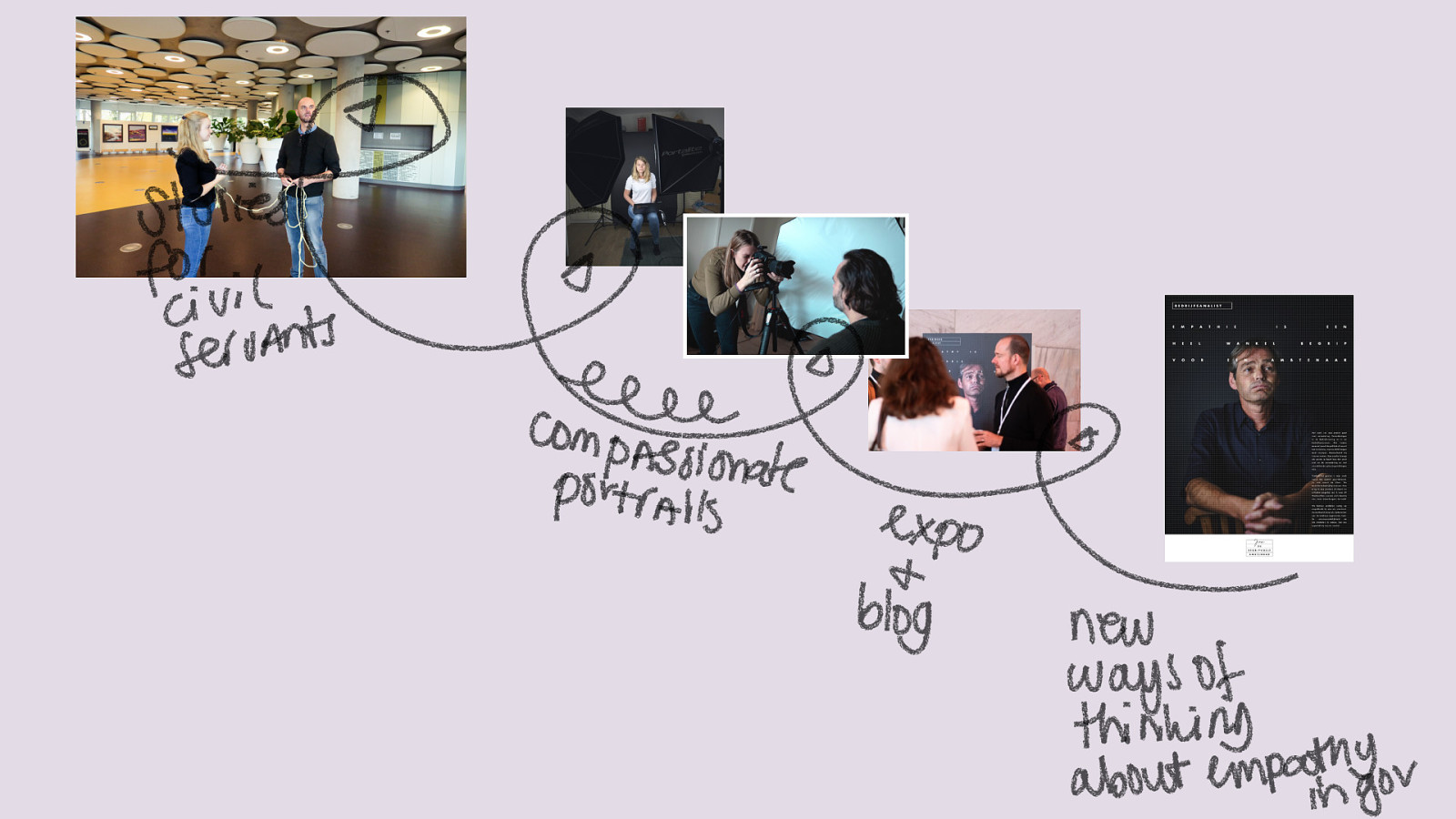

I have been photographing my colleagues asking them how compassionate they are towards the citizens and what role empathy plays in their work. I have been a photographer for over 10 years, and I am also a UX researcher. In this project I combined both.

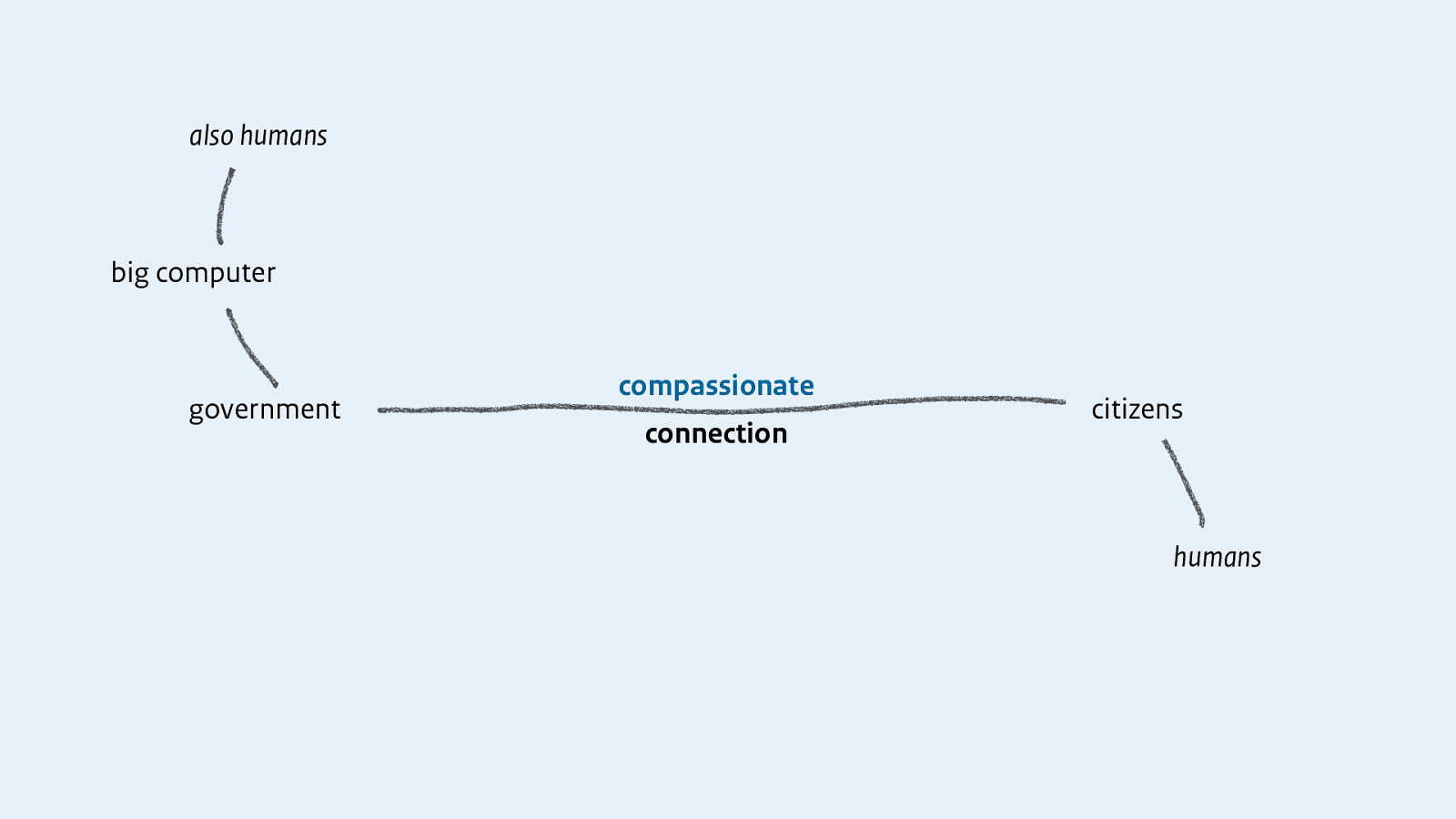

My research question was: how can we, as digital government, have a compassionate connection with citizens.

I wanted to know what that means for the people who make digital government. They are the civil servants that we never see. They are the managers, developers, security specialist, the copy writers and the policy makers.

We know technology isn’t neutral and makers have their own bias. My research is to find out who we are as civil servants and how our biasses impact the digital relation that citizens have with the government.

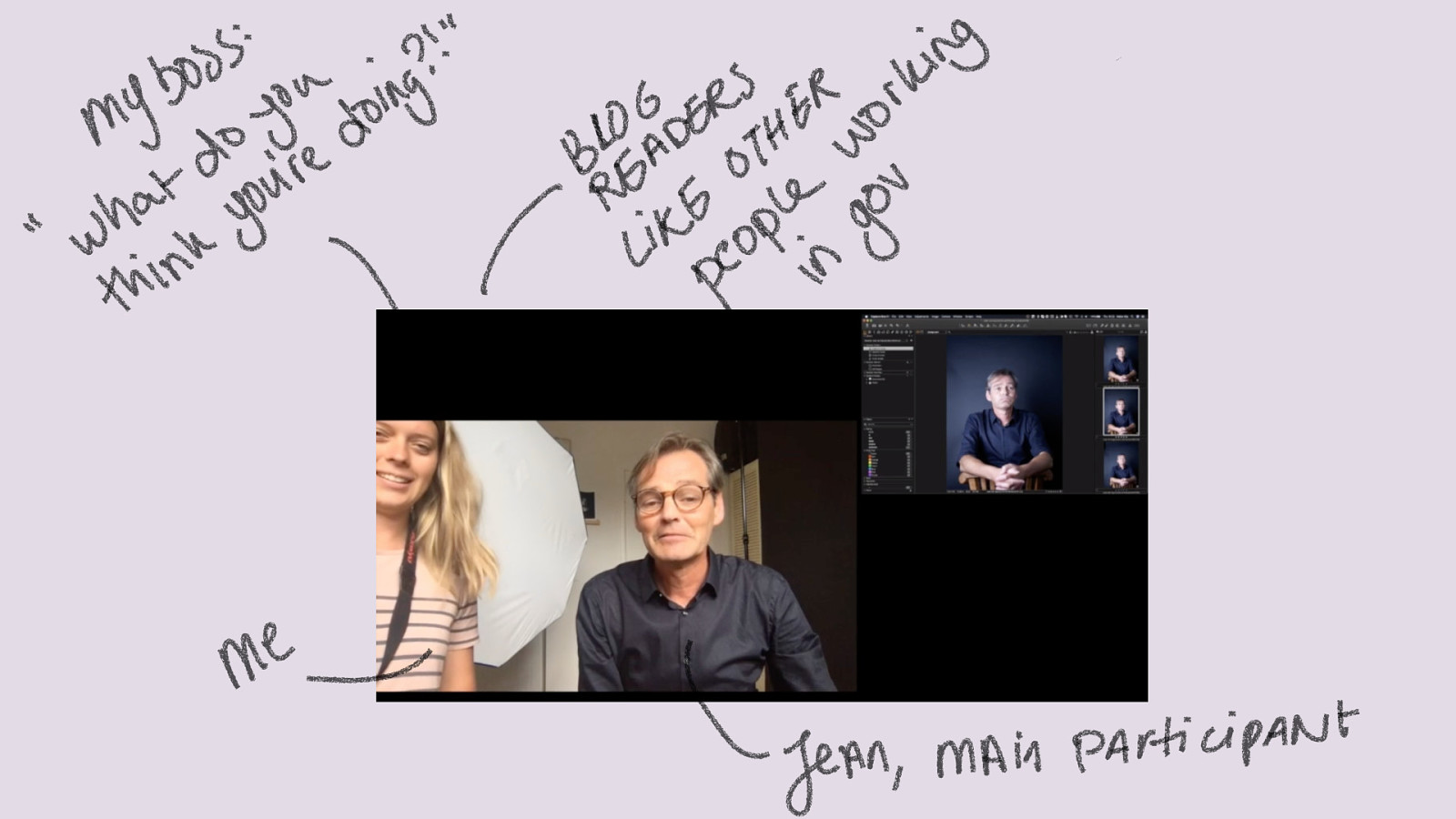

This is not an easy conversation. A lot of the times we don’t talk or reflect on these issues. I use photography because that’s a way that I can express myself in. I designed a research method called photo-interviewing which helped my colleagues to express themselves as well. For example Jean.

(In this video you see Jean being photographed and choosing his portrait. Hij choses the portrait where he’s thinking and looking frustrated because for him as a civil servant empathy is a difficult topic).

This is the most important moment if you ask me. My participant looking at themselves, and reflecting on their own image. Is this how I want to express myself and to show myself as a compassionate civil servant?

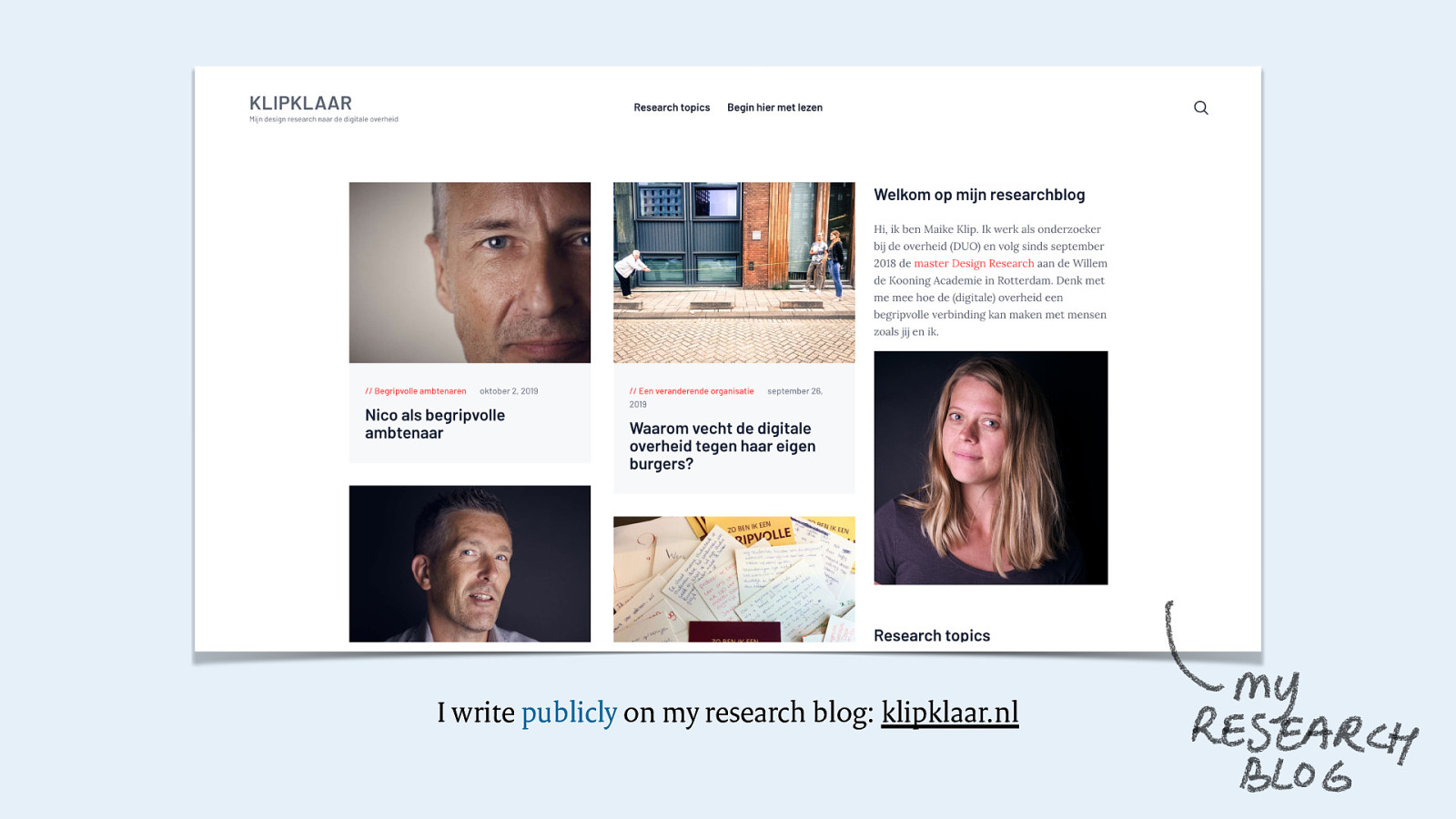

I publish their stories and portraits on my research blog. So everyone can read it, but can also chip in on the conversation.

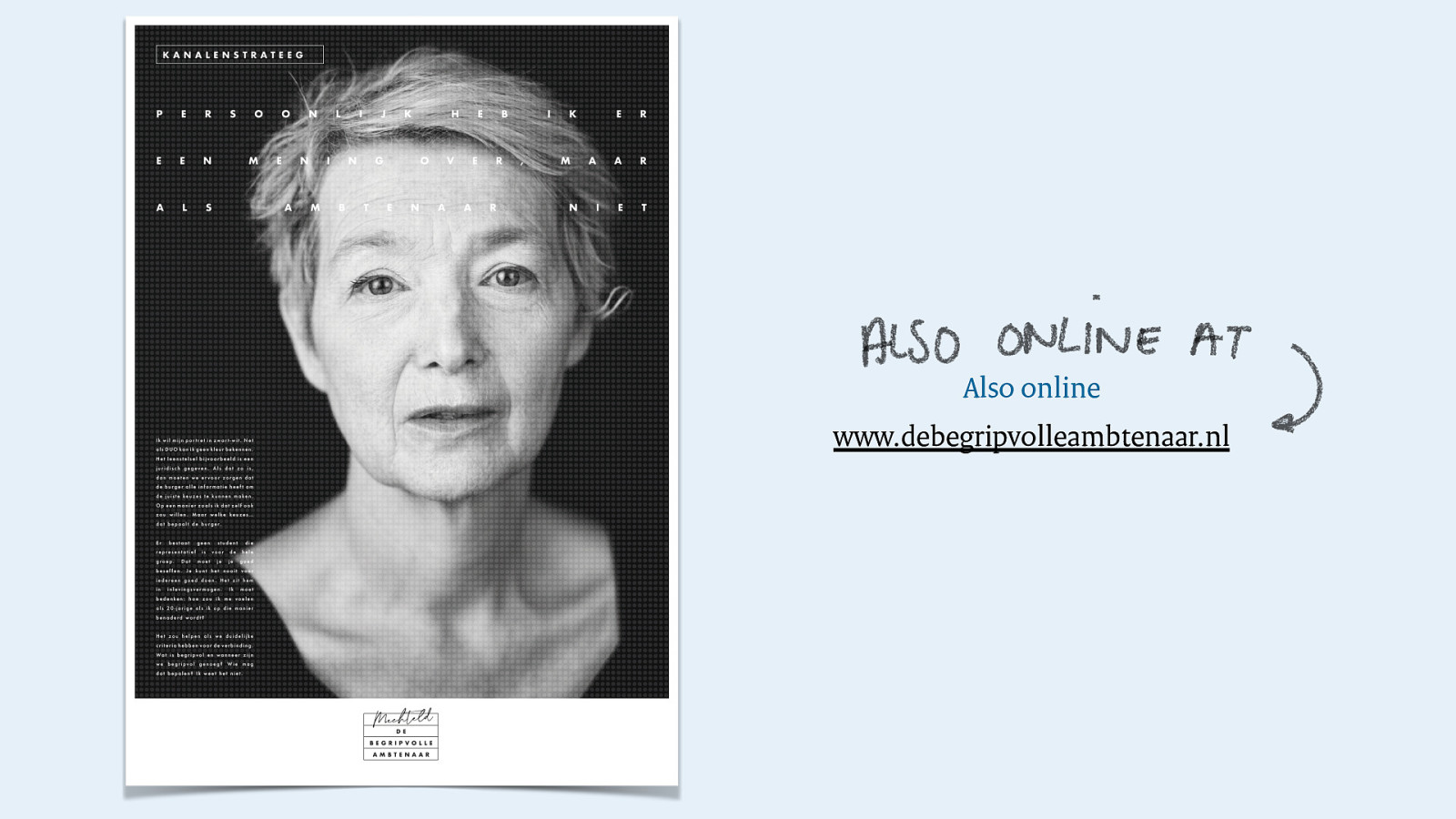

I also made a digital and physical photo-expo as to further research and spur the conversation about this topic.

This summer I concluded this research project and wrote 9 essays about the insights that came out of all the conversations that I had. The essays are about the struggles that civil servants have working in digital government and the ways that we can overcome those struggles and truly be compassionate civil servants.

You can read the essays (and the personal stories) at www.debegripvolleambtenaar.nl.

But today I am not going to talk about working in government nor about the insights I discovered doing this research project. I am going to talk about the method that I designed doing this research.

First let’s dive into some theory about artistic research.

Why do we even research? We do this to understand how others feel about certain things, how people use products so we can optimise them. How problems are, we untangle them to better understand the complexity and to come up with solutions. In general we research to better understand the world around us. We want to make sense of it all.

Our insights can be turned into solutions, into product or change the way we think about things.

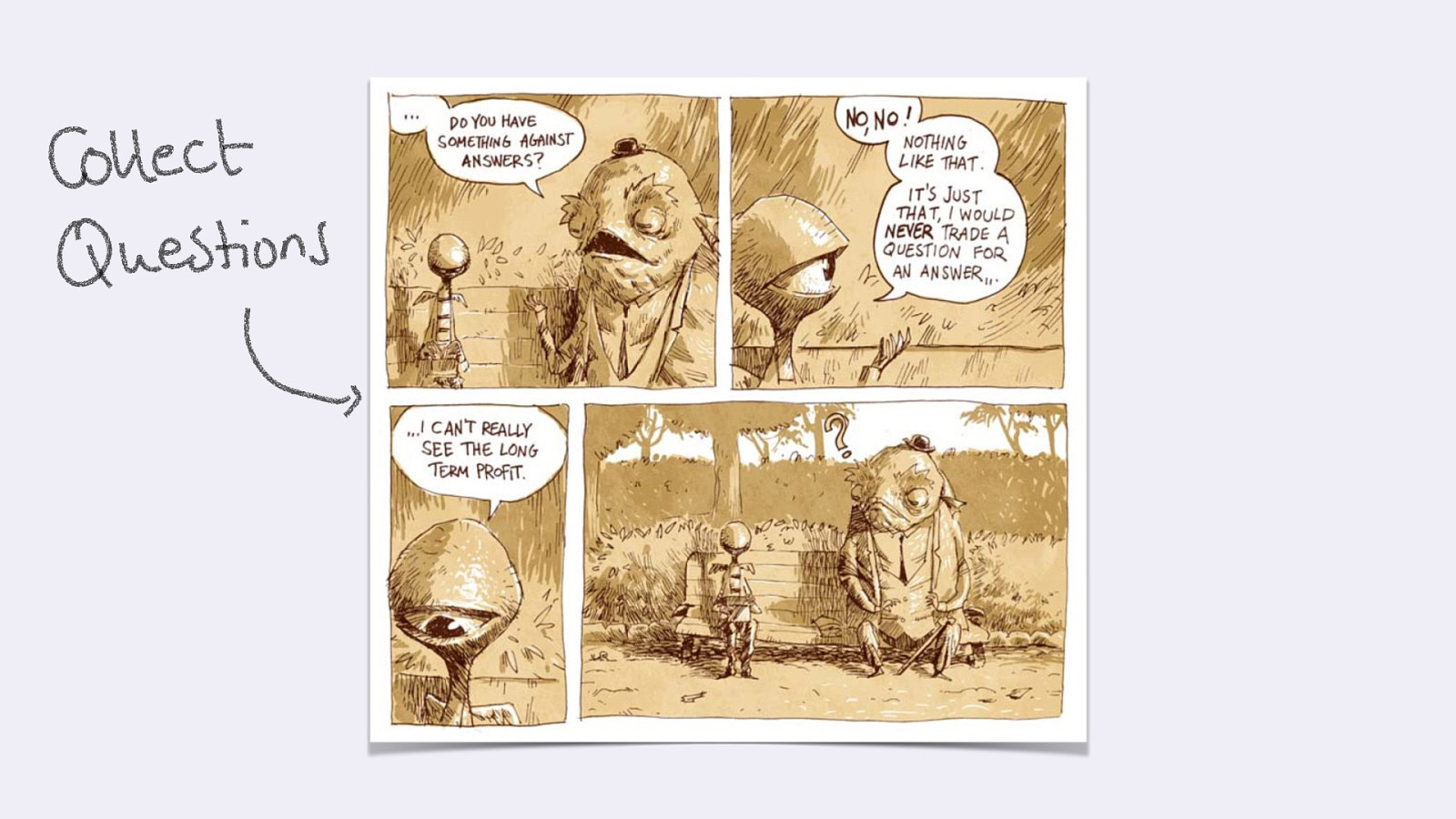

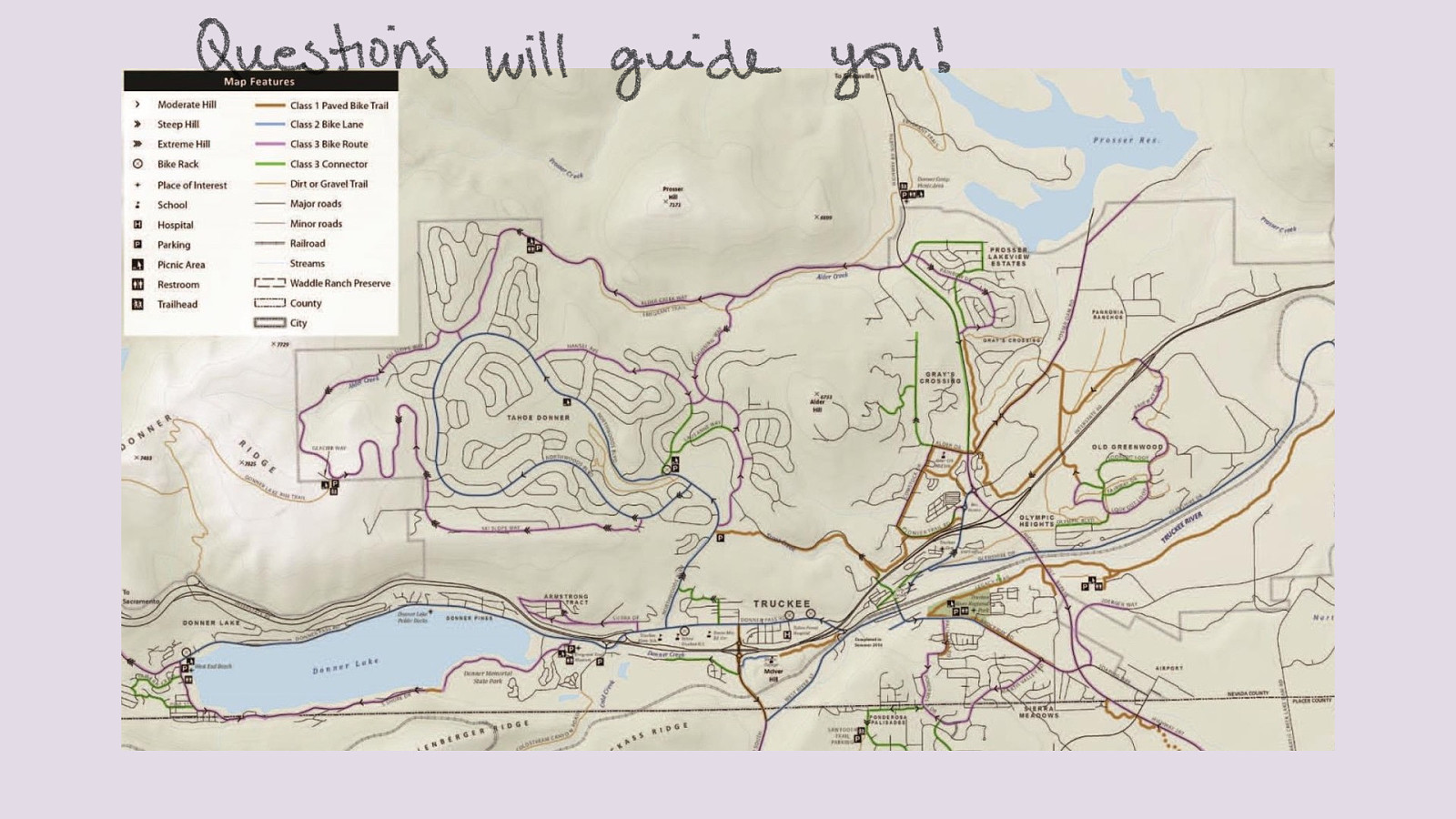

A research project always starts with an interesting question. I love this comic called A Day in the park. There’s this little fella who collects questions, and the big one can’t imagine why someone would do that. What follows is a very long and interesting conversation about the beauty of questions.

Questions are amazing. They are the first thing you need to start making sense of it all.

Read the comic here: http://kiriakakis.net/comics/mused/a-day-at-the-park

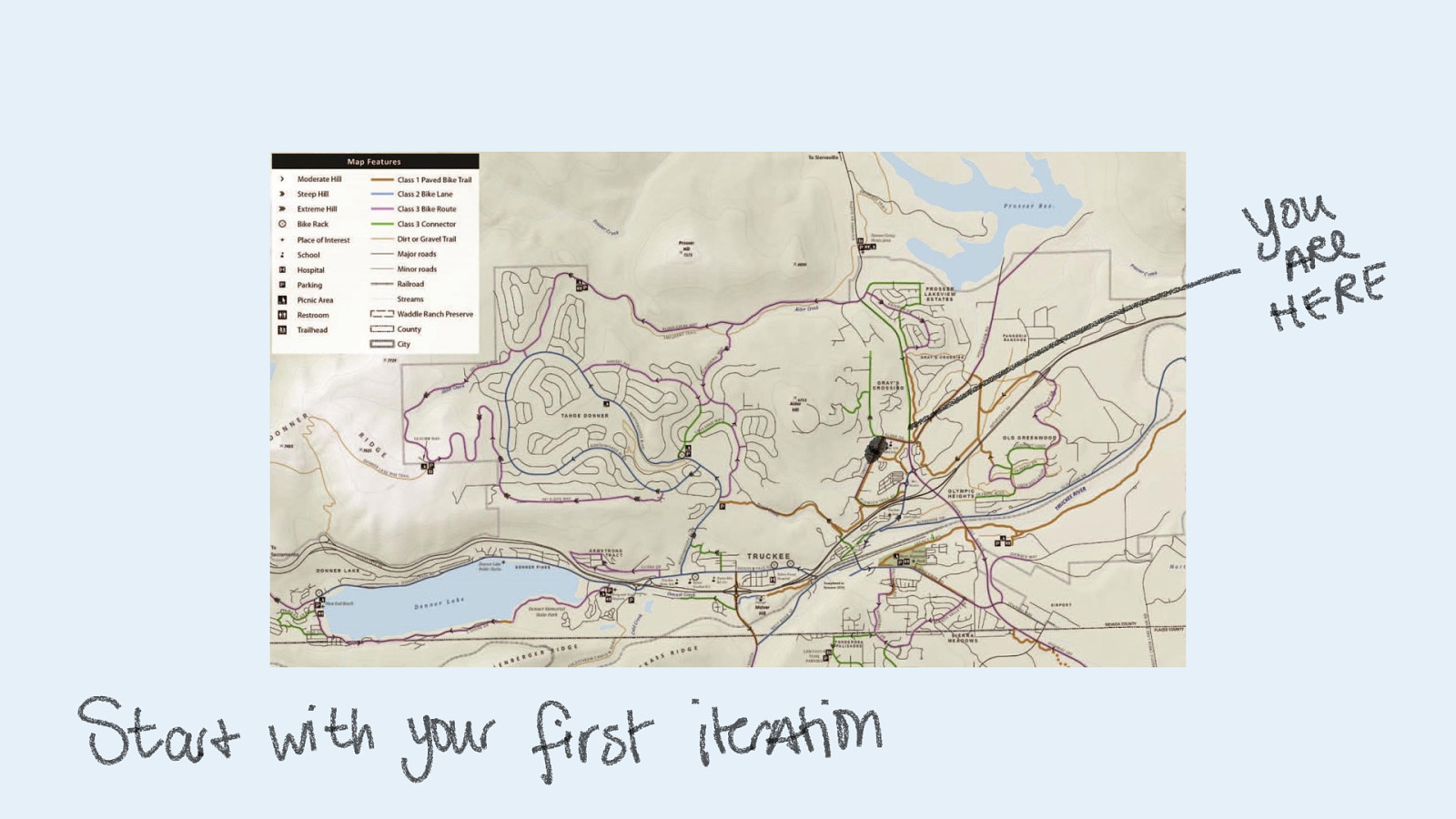

I see a research project as making a map. You start at one point with the information that you have at that time. But once you take one step, you look one way, you find out about something, you start hiking, you might say. Questions will make you hike.

One question leads to the next one, as one path will leads to another one. And only by starting to walk, you can find your way. Only by starting to ask questions, you will find your way.

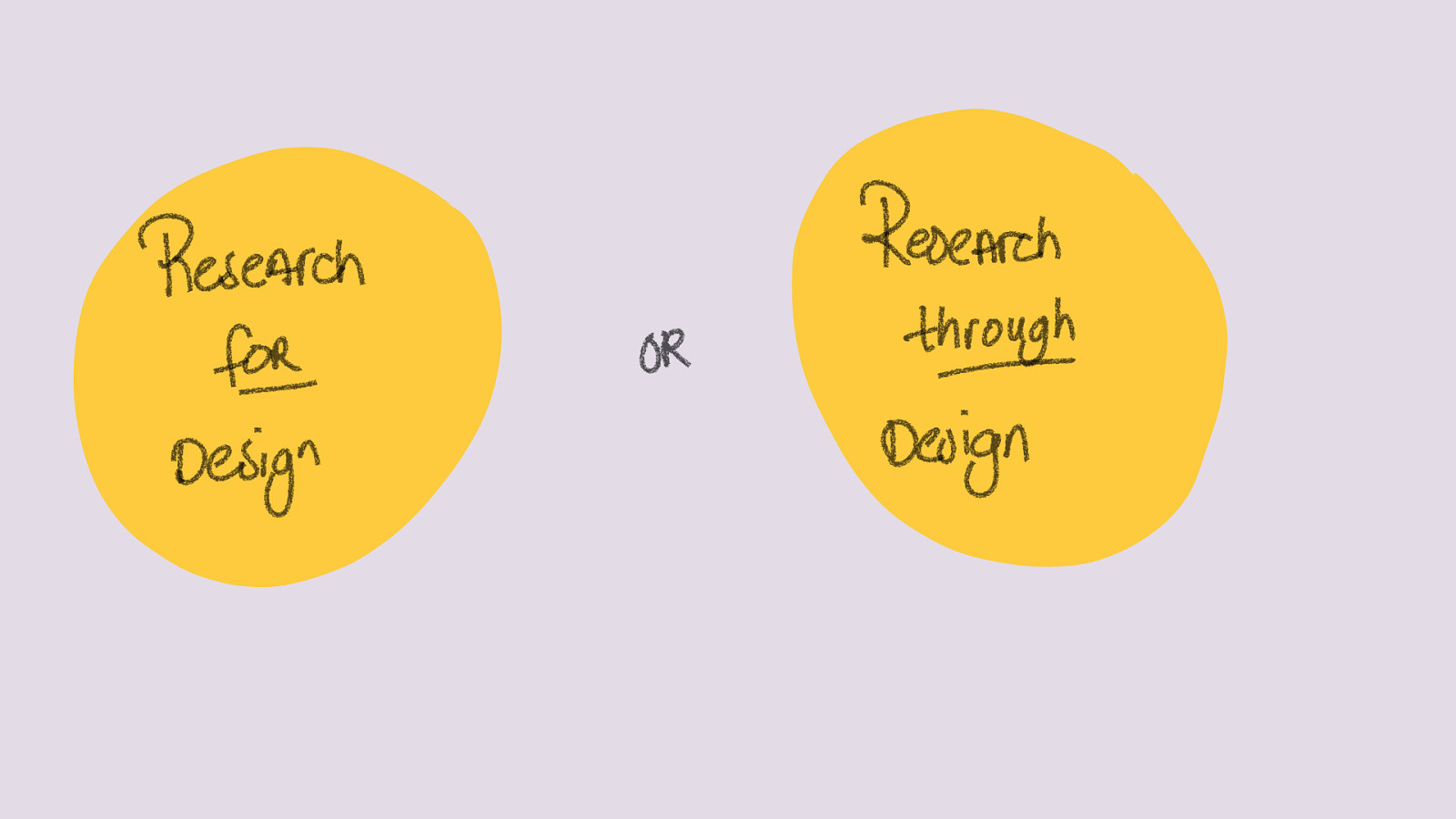

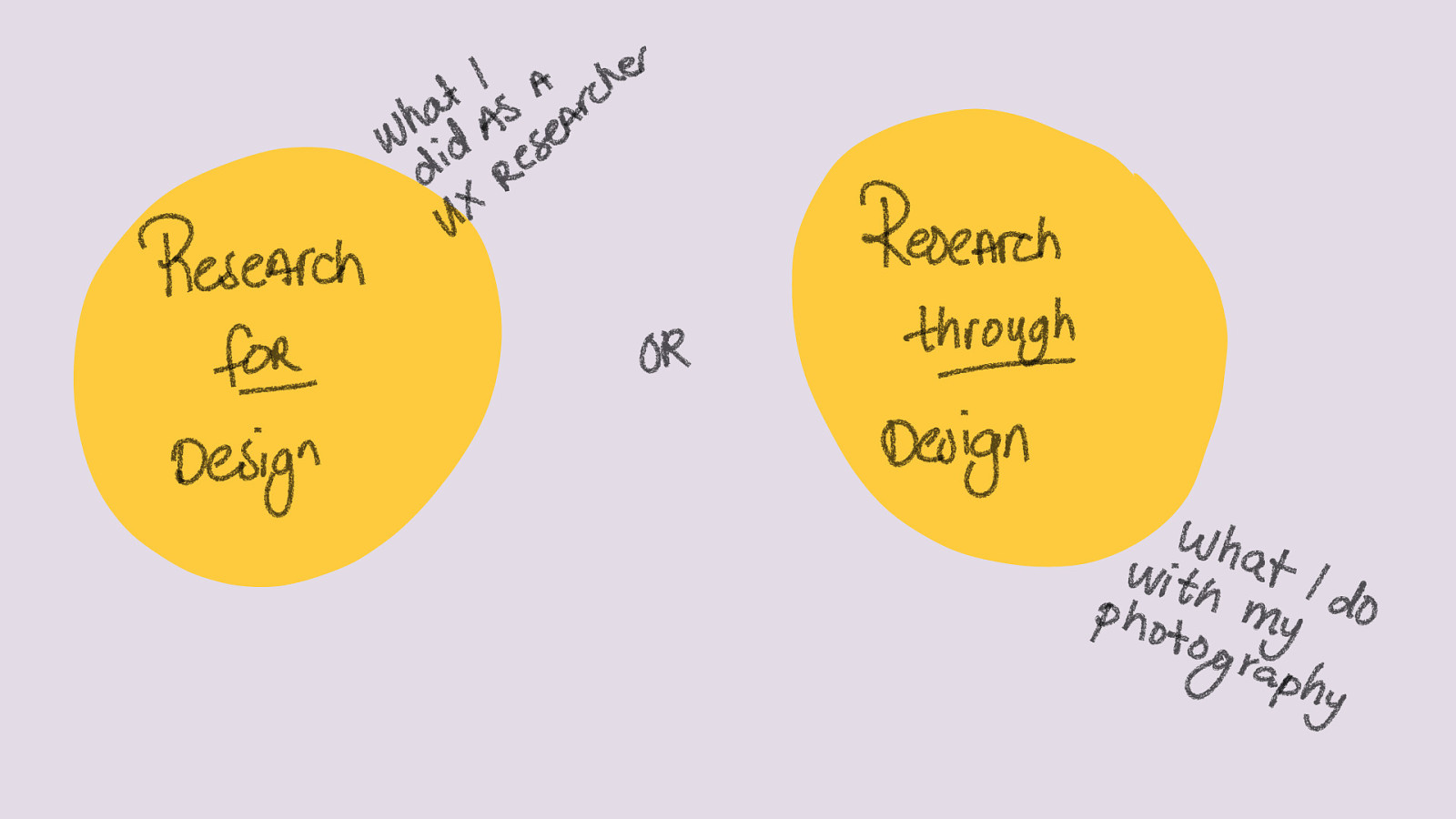

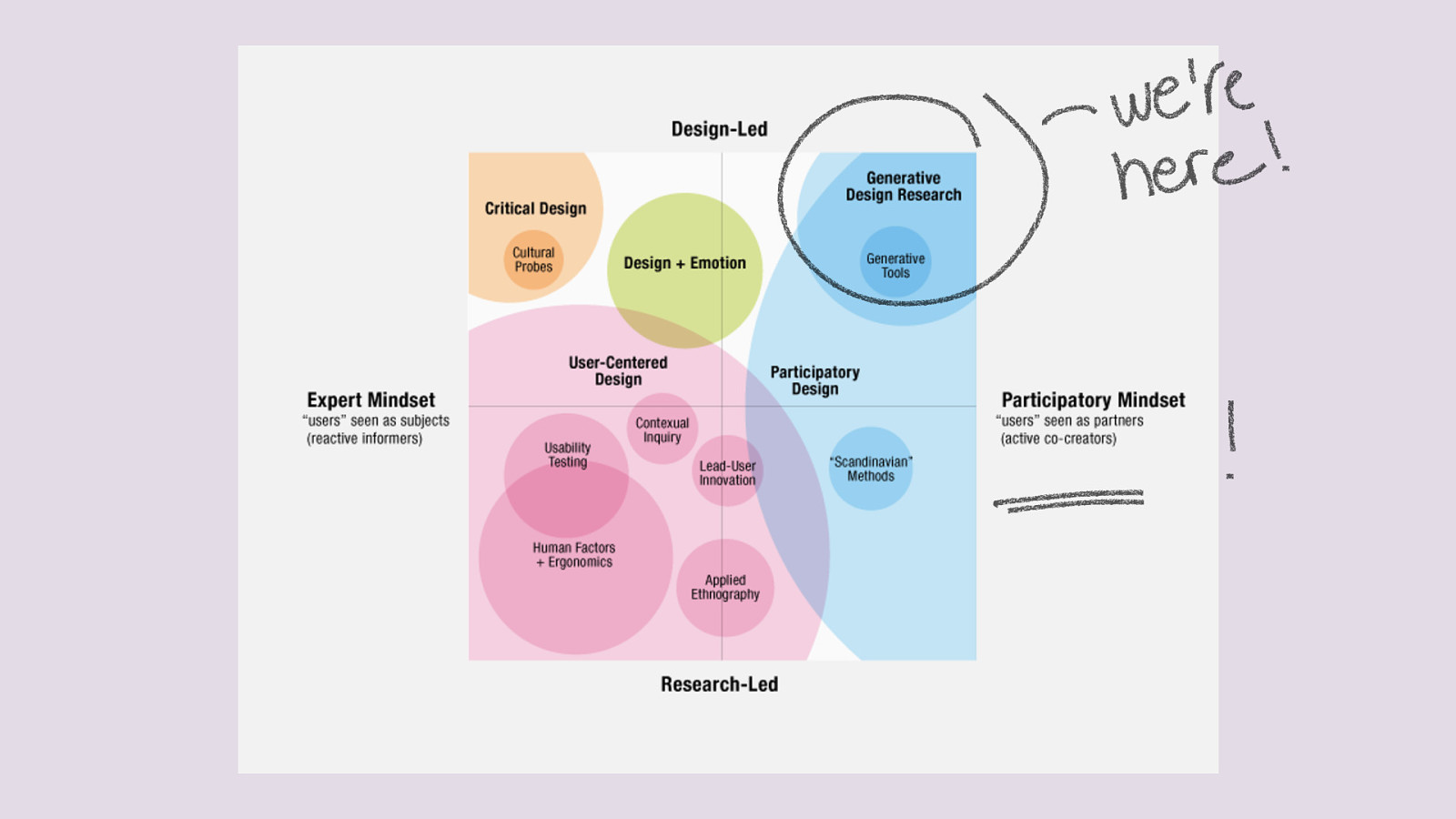

So what is design research, and how is it different of UX research, the one we’re all familiar with here at UX Insight?

When I started my career as a UX researcher I did research for design. I interviewed and observed users, and my colleagues used the insights I gave them to make applications for users. I literally researched for my design colleagues.

But what I am going to talk about today is using design to do research. Doing research not for, but through design.

The role of design in design research is not a product but the research itselves. We design so we understand the world better. We design so we find our answer to our questions. We design the find our way in the forest.

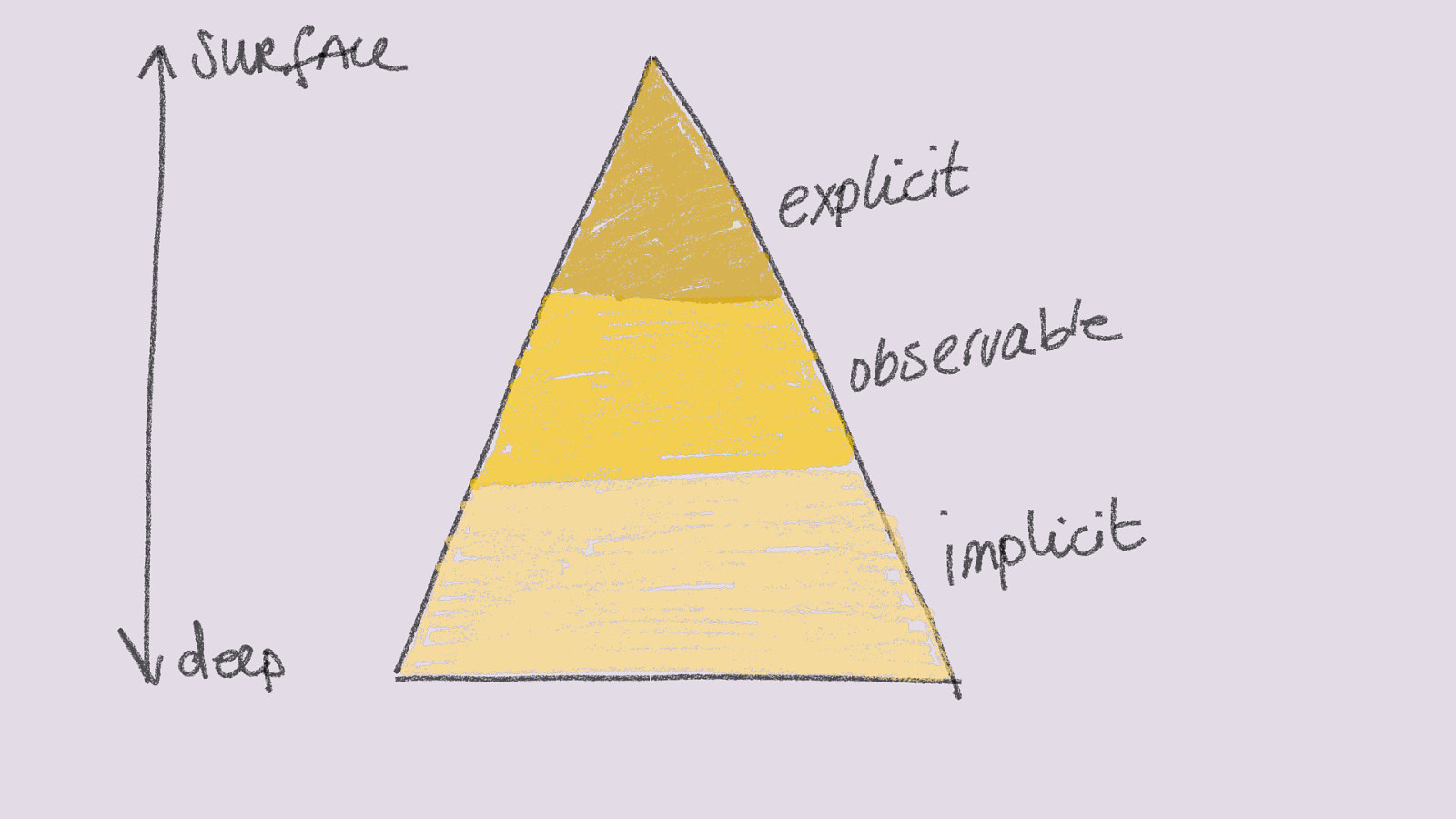

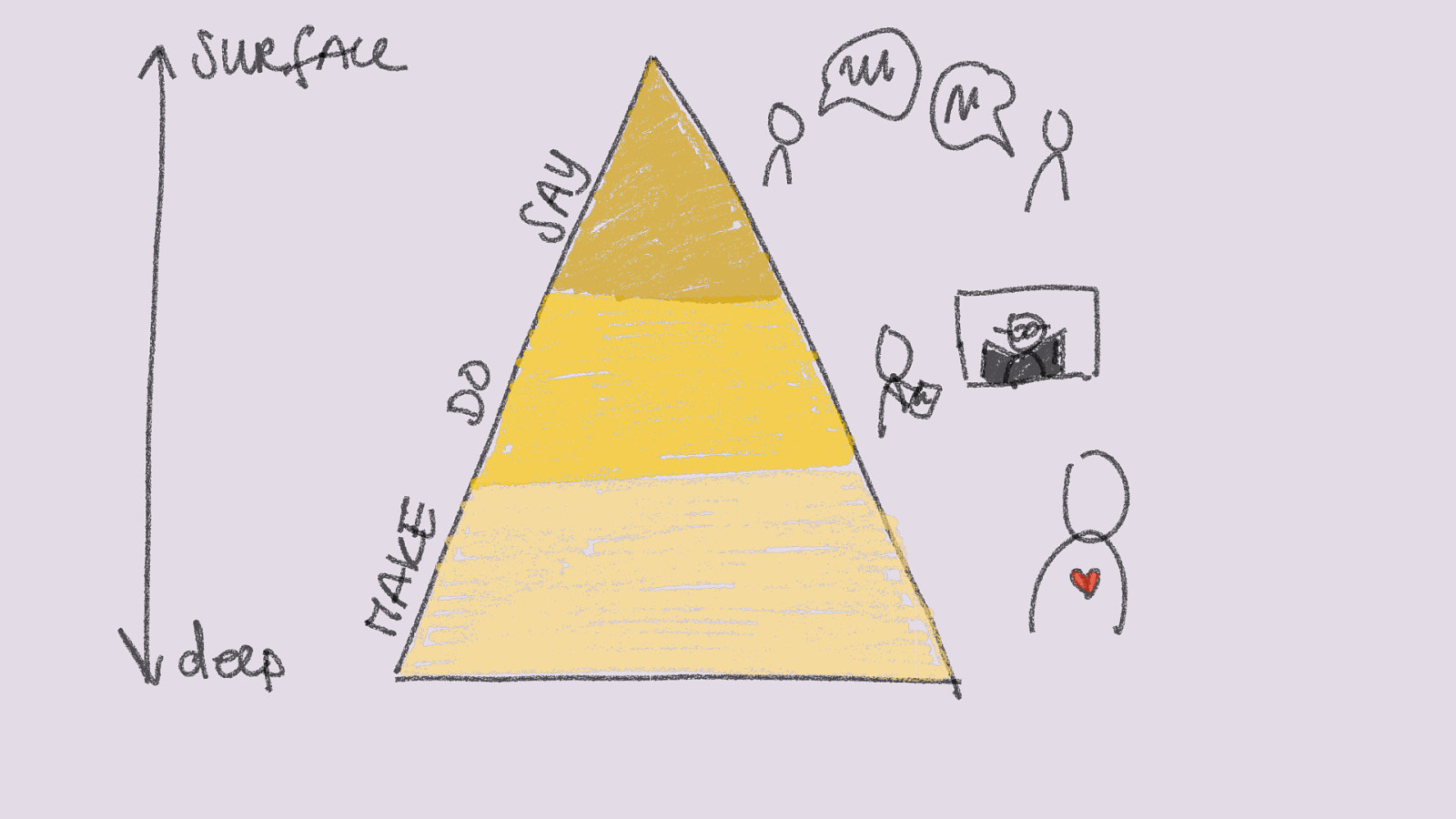

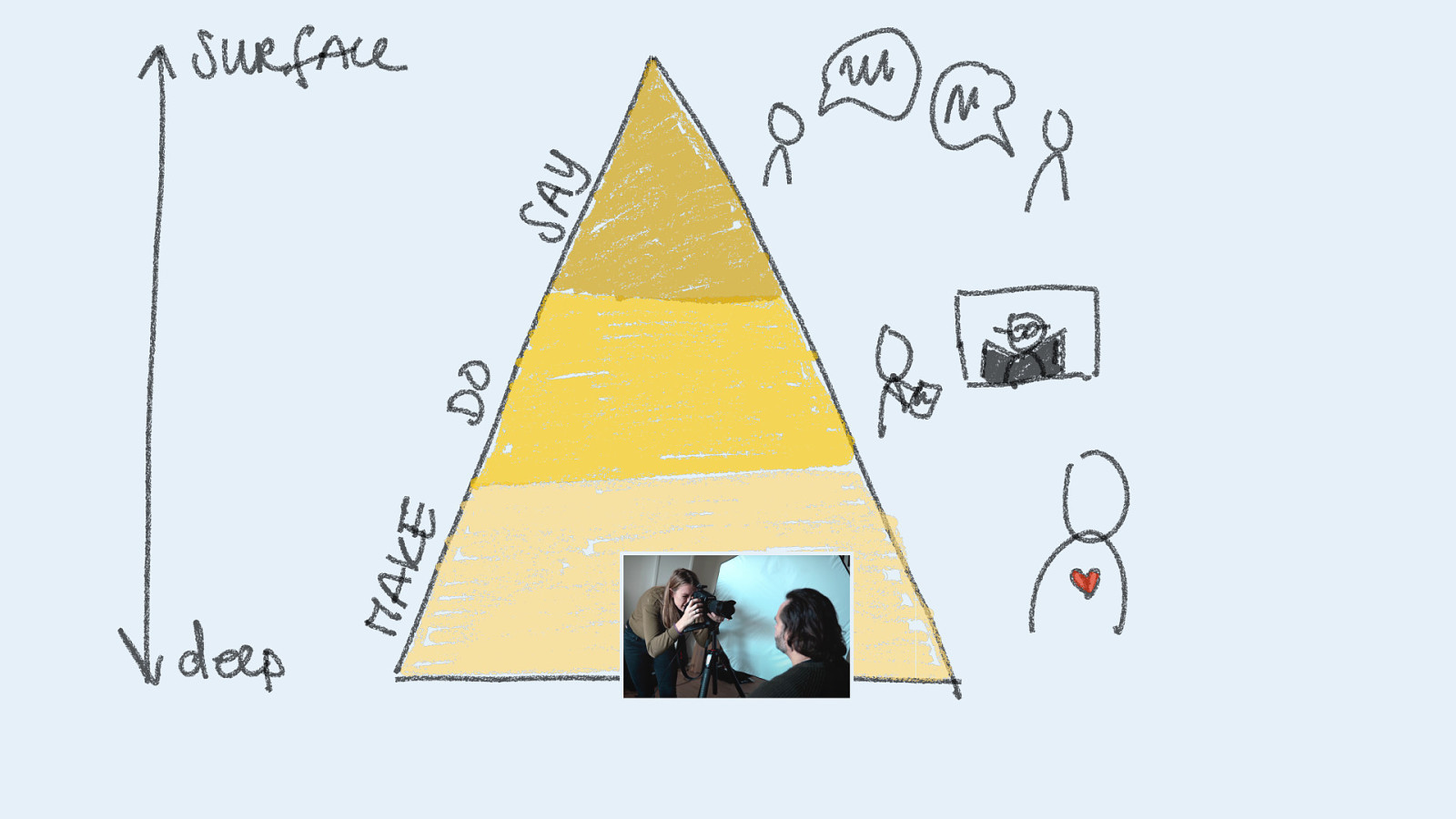

When interacting with participants we can easily see the explicit and the observable. We can interview, talk to participants and we can observe them and see how they use a product or how they go about their day.

But there’s more that’s below the surface. People have implicit knowledge. Those are the things that we don’t know we know or don’t know how to express them when you ask about it.

Or when you have very intense feelings about something and you don’t know how to talk about it. Then you hear a song or someone gives you a hug and you feel all the feelings without being able to talk about them.

These are the deeper things under the surface.

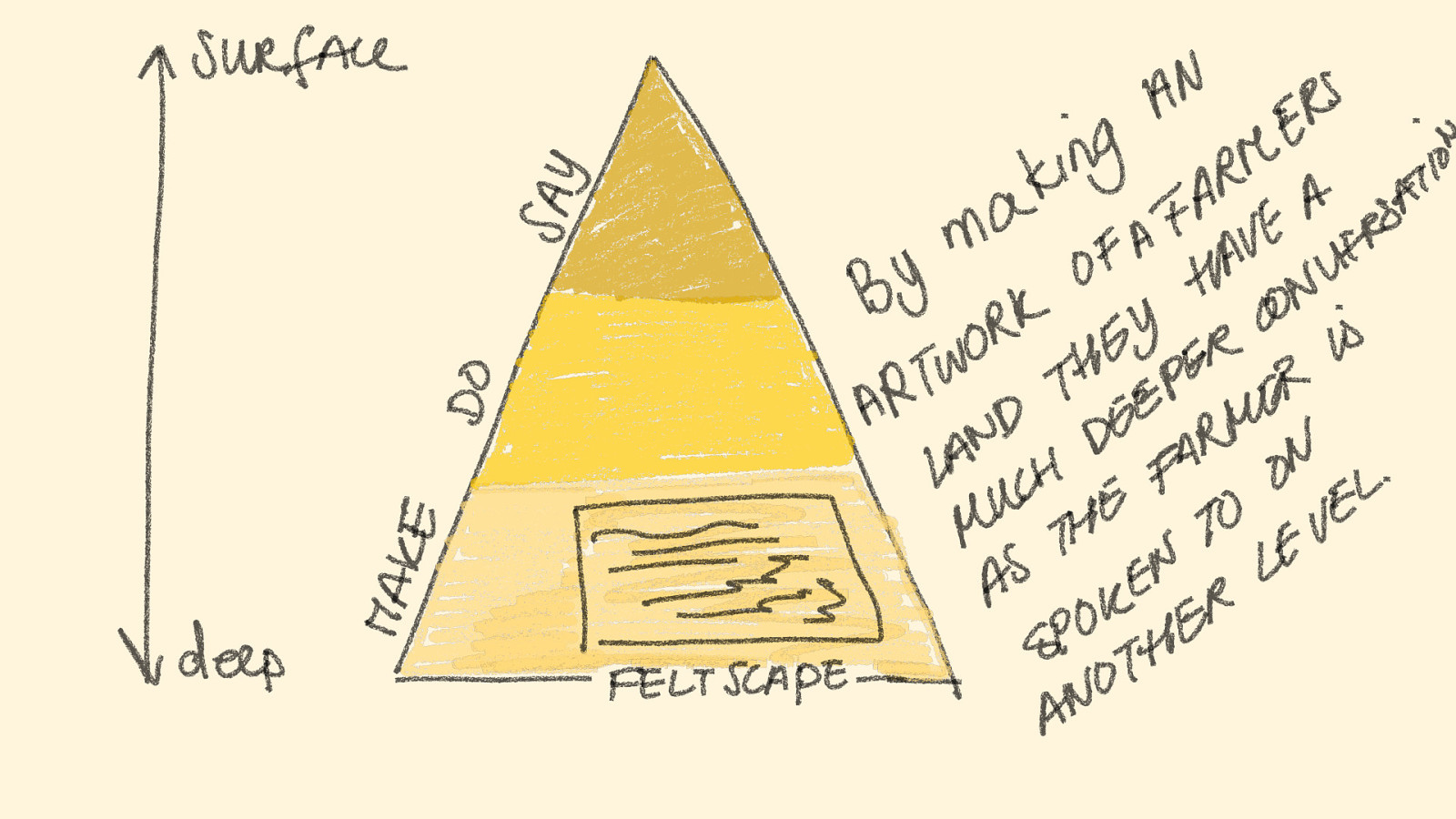

To research these different layers, we have different methods. They are the say, do and make methods. Today I want to focus on make methods.

I love using art for this. Art is also about seeing, experiencing and feeling. The work of an artist, wether or not we are involved in the making process, is always sensory. You can experience it. It speaks to us on a much deeper level.

I’d like to show you some work of other design researchers that have inspired me to do my own research project. Some of these designers I know very well, some I just admire there work from afar. However I think they are all very great.

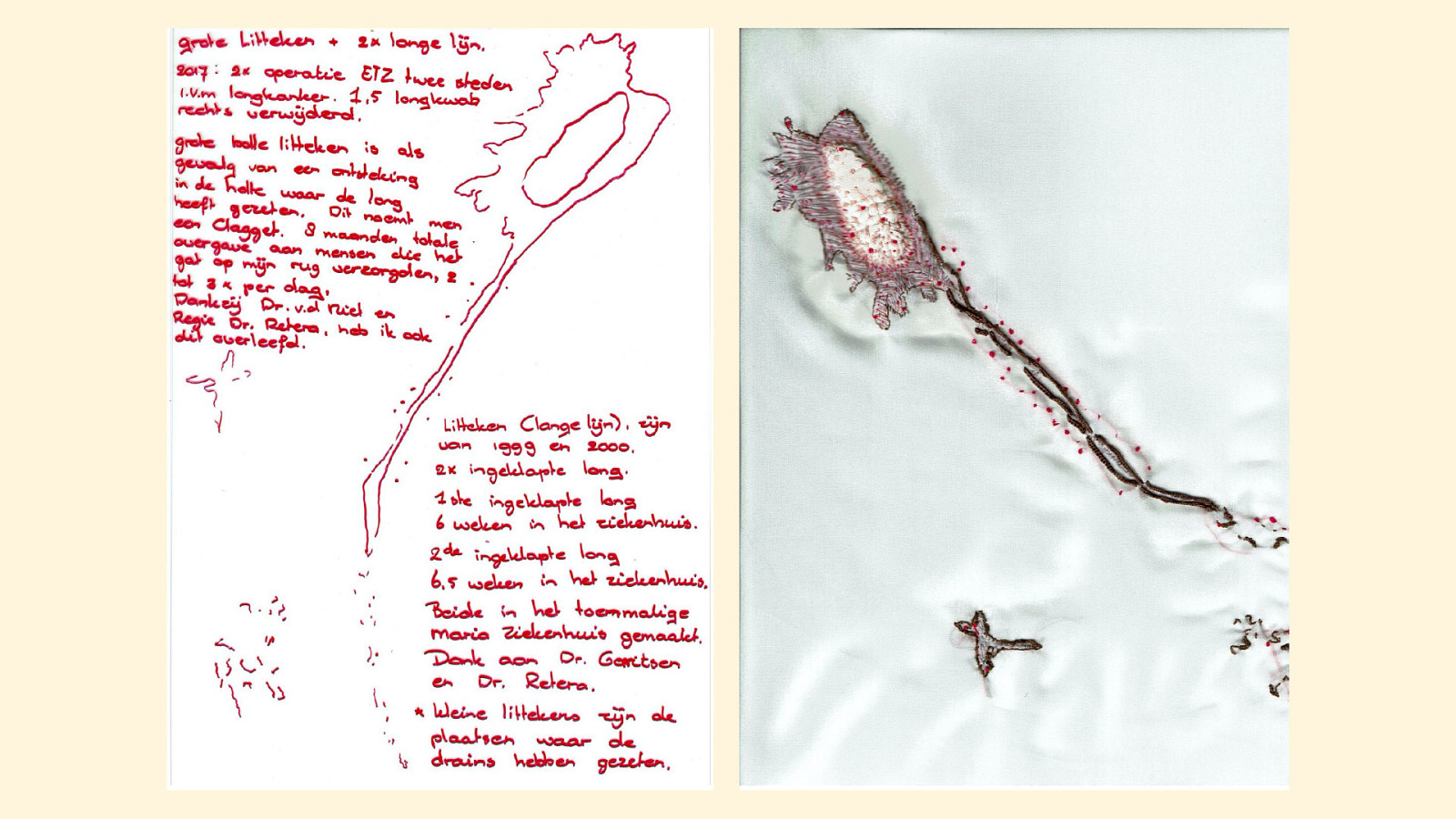

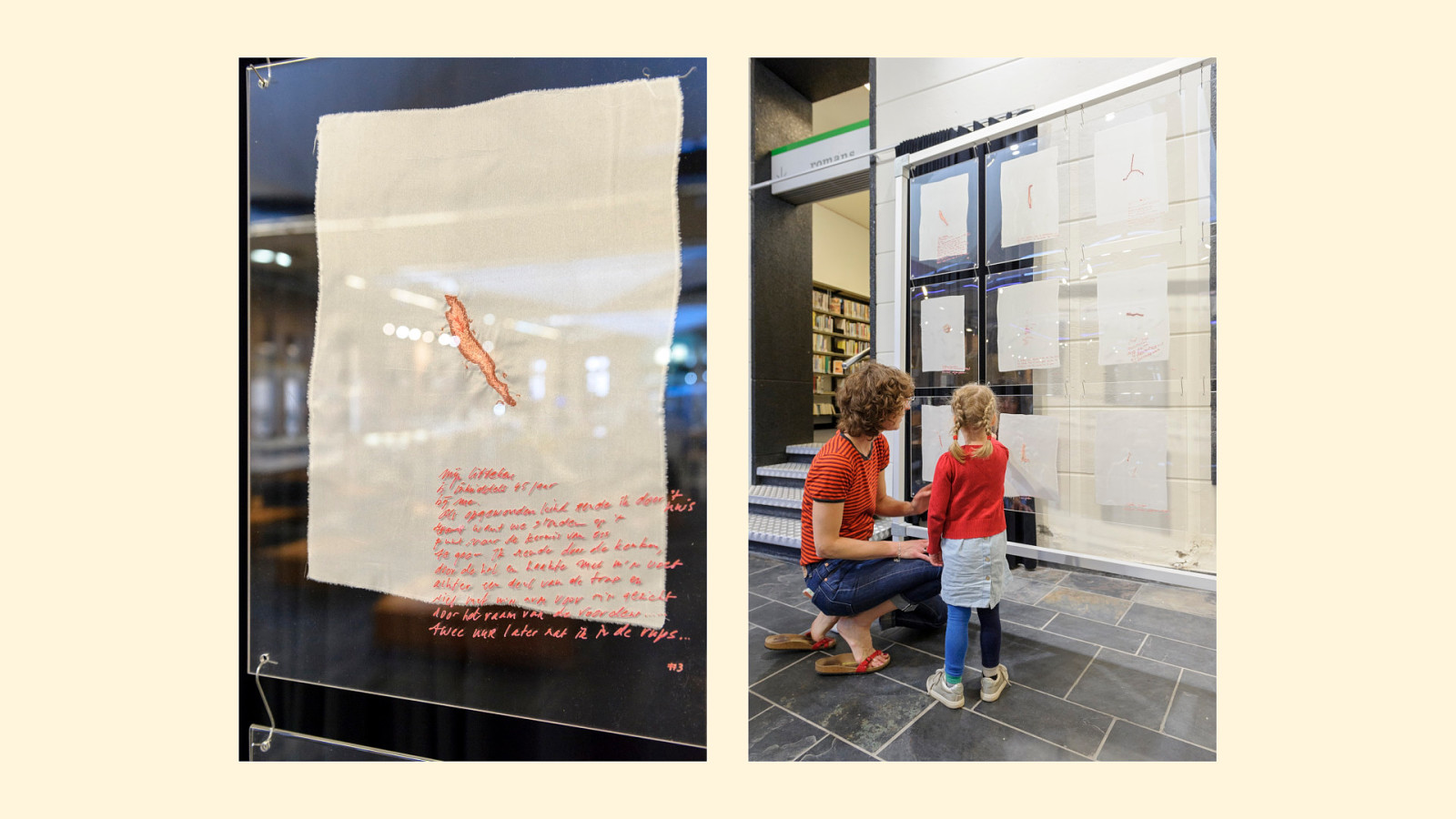

Encounter is an art based research project from Joost van Wijmen. He has a background in costume design. Encounter 6 is an exhibition of embroidered scars and their stories.

Joost designs so called Encounters where he draws scars from participants which are later turned into beautiful embroidery. People share their stories with the scars and Joost collects them and turns them into art works.

It is a very intimate moment where he literally touches your body and draws the scar on transparant foil. Because of his background as a costume designer he knows how to work with this intimacy.

In the same setting there is another person doing live embroideries from other scars so the participant knows what to expect. The whole setting is very much designed and thought through by Joost.

He is setting up these encounters in libraries, hospitals, and other public spaces and people are traveling from far to be a part of them.

By doing this he collects implicit stories behind the scars. He asks the participant to write their story along side the drawing that he made of the scar. These stories are as much part of the encounter as the embroidered scar is.

But why does Joost do this? Apart from the beautiful stories that he collects, he uses them to research the meaning of scars and the way our society deals with brokenness and vulnerability. By making the scars into an art work he transforms a by-product (the scar) of surgeons and hospitals into something that people can experience and talk about. The implicit gets explicit and this leads to a conversation between doctors, other care stakeholders and patients that otherwise wasn’t possible on this level.

The embroidered scars become part of an exhibition that travels to care institutions and hospitals. The scars and the stories function as conversation pieces for care workers to discuss and reflect on. Joost is working to involve more surgeons and medical staff in this project. For hospitals it is very interesting to be a part of Encounter because Joost has managed to make a vulnerable topic rise to the surface.

Read more about Encounter and Joost van Wijmen’s work at https://project-encounter.nl/

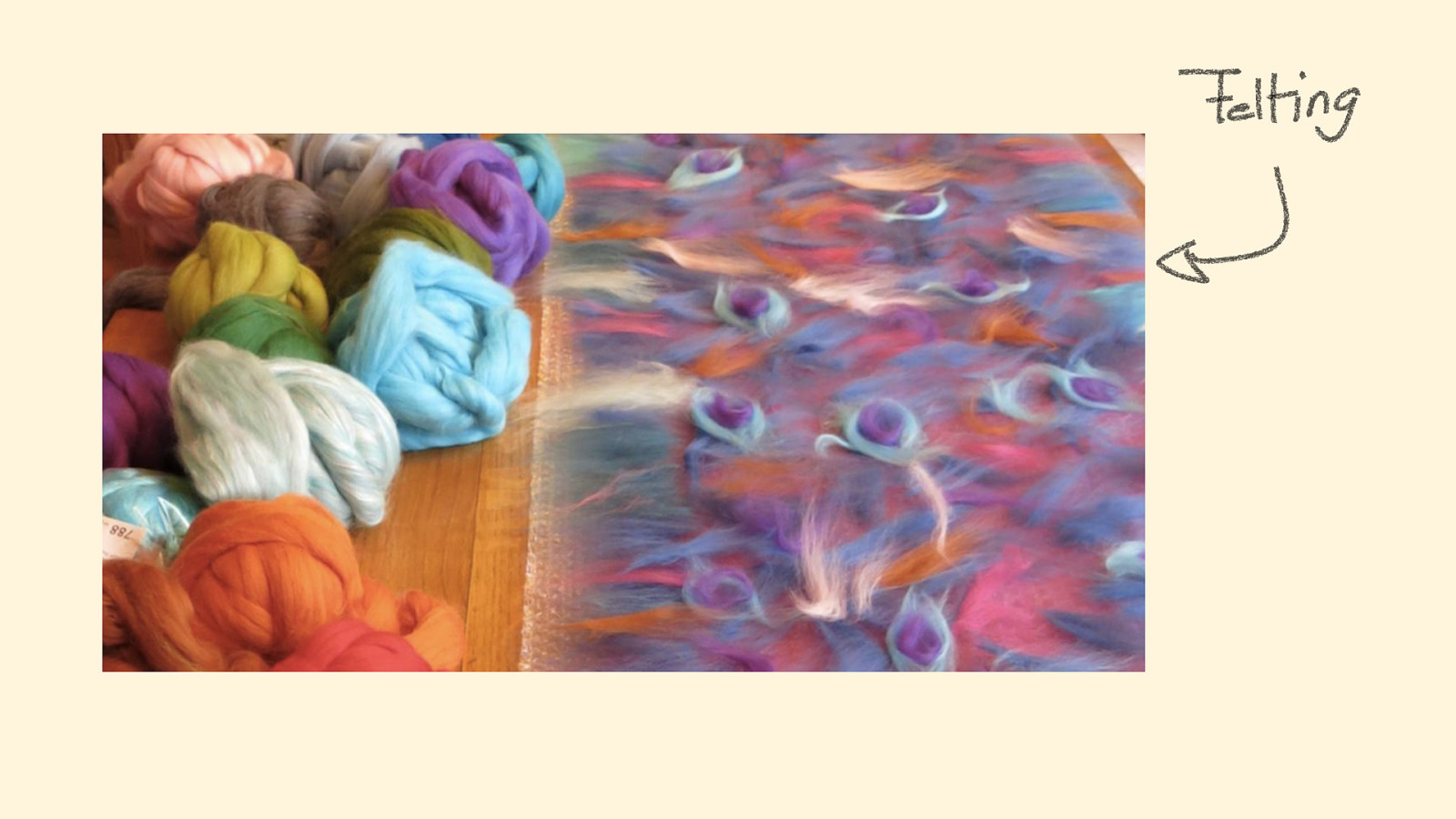

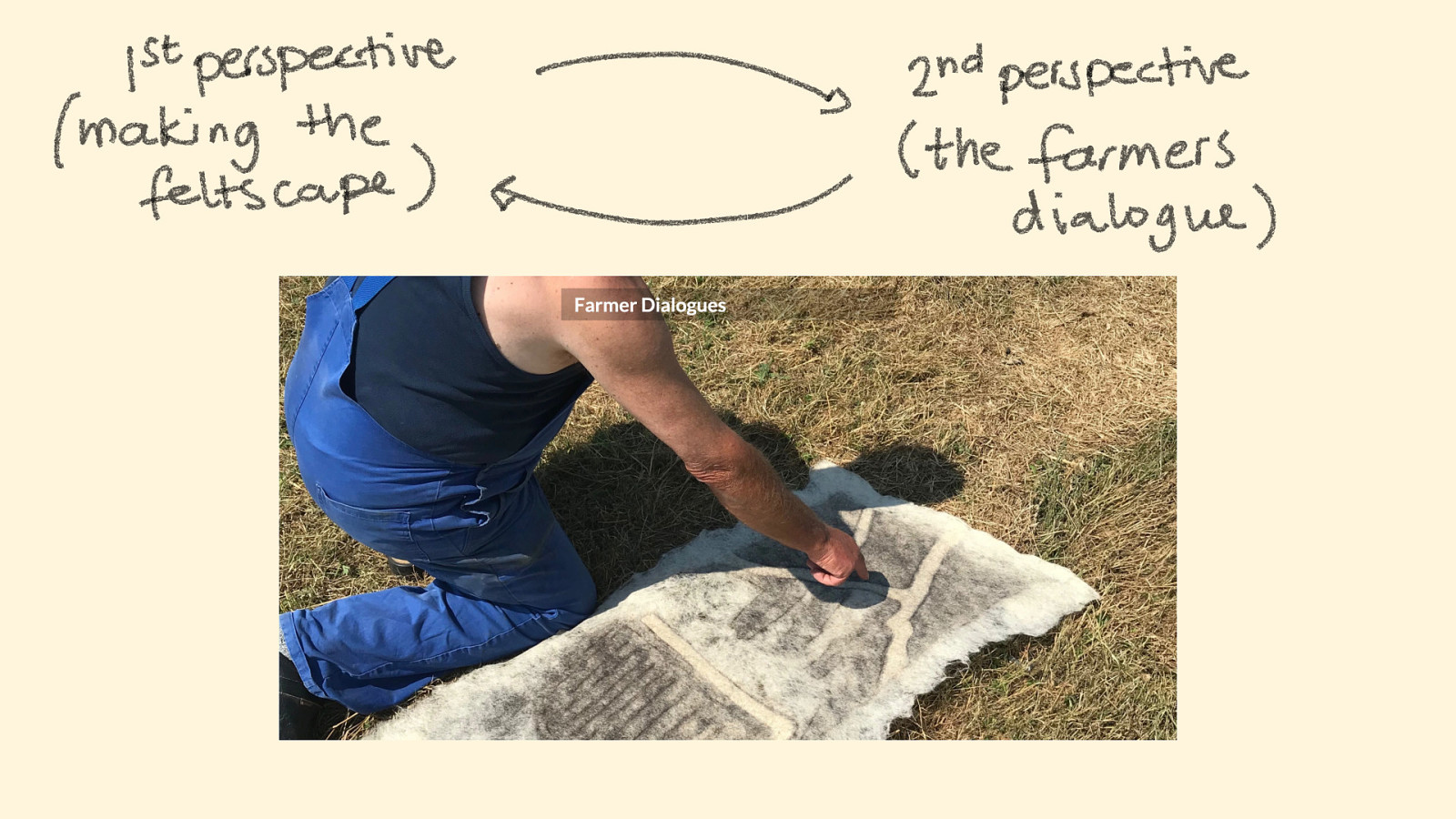

The next art based research project is from Cora Jongsma. She is a landscape historian at the University of Groningen but she also felts. She combined these two into Feltscapes.

Felting is an old technique where you can make textile of wool. Before I met Cora I never heard about felting before, to be honestly.

In her work, Cora studies the land and is particularly focused on the height difference within the land and what this does ecologically. She works with farmers and other land owners and does academic research into these topics.

And she does artistic research. She translates her landscape studies into, what she calls, a Feltscape. Because she studies the height differences this is ideal for felting.

With these Feltscapes she organises ‘farmer dialogues’. This is exactly what you think it is. A farmer has land, Cora makes a study of the land and turns that land into a Feltscape. Yes, it takes hours of work. With the end product she goes back to the farmer to discuss landscape issues and has tough ecological conversations with these farmers.

Dutch farmers are very stoic but their land is their everything. So you can imagine how different these conversation are when you have a notepad on you or a personally made Feltscape of the land where the farmer has been putting his soul in every day.

You put hours in, but they have been putting years in. So these farmer dialogues that she has with farmers have been resulting in much richer insights than if it were ‘just academic interviews’.

Read more about the Farmer Dialogues: https://feltscape.blog/farmer-dialogues/ Or https://www.lc.nl/friesland/Reli%C3%ABf-van-een-landschap-in-vilt-22853489.html?harvest_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F (dutch)

The implicit is made explicit because farmers can feel, show, point, and experience their land on a whole other level.

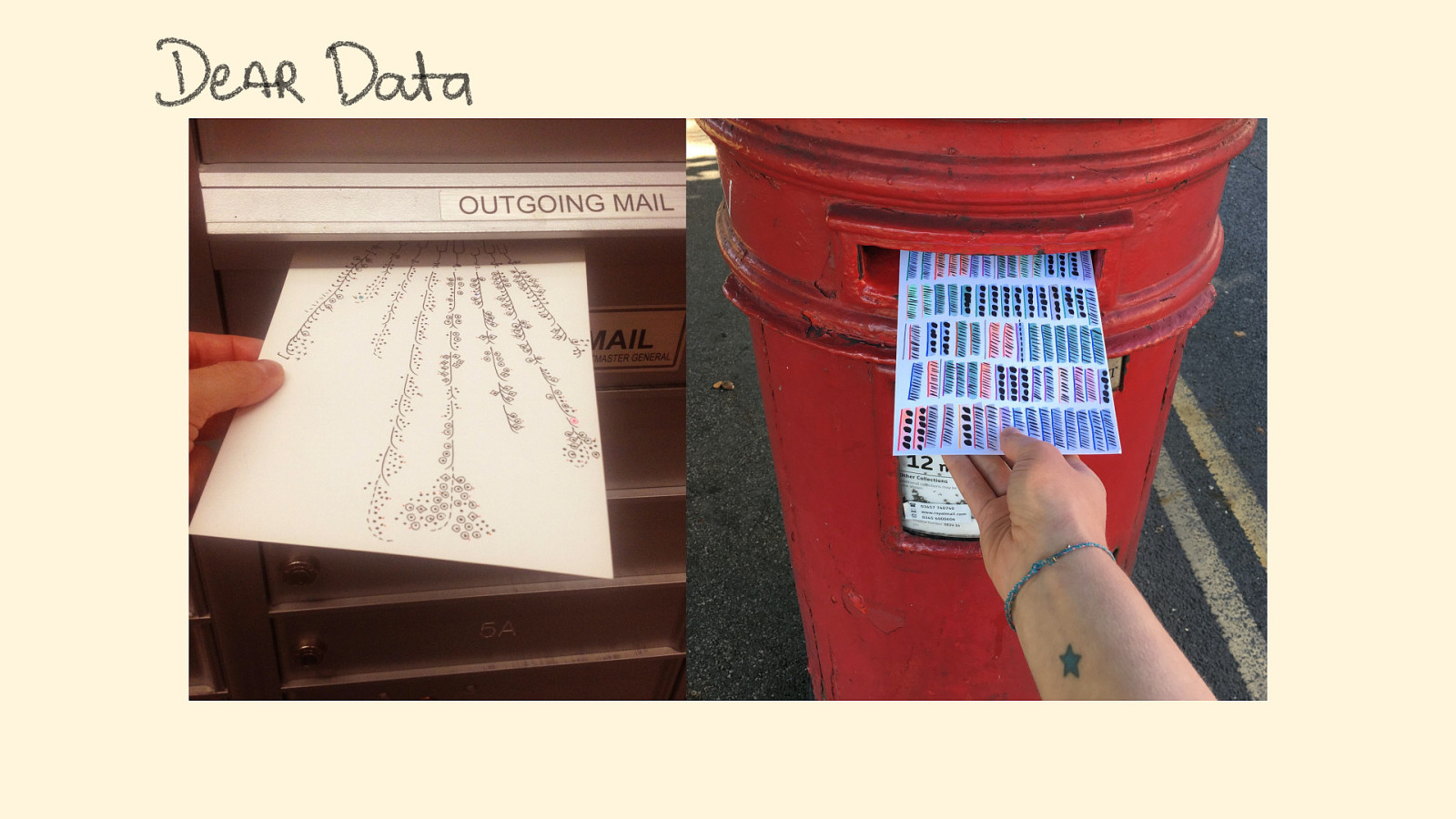

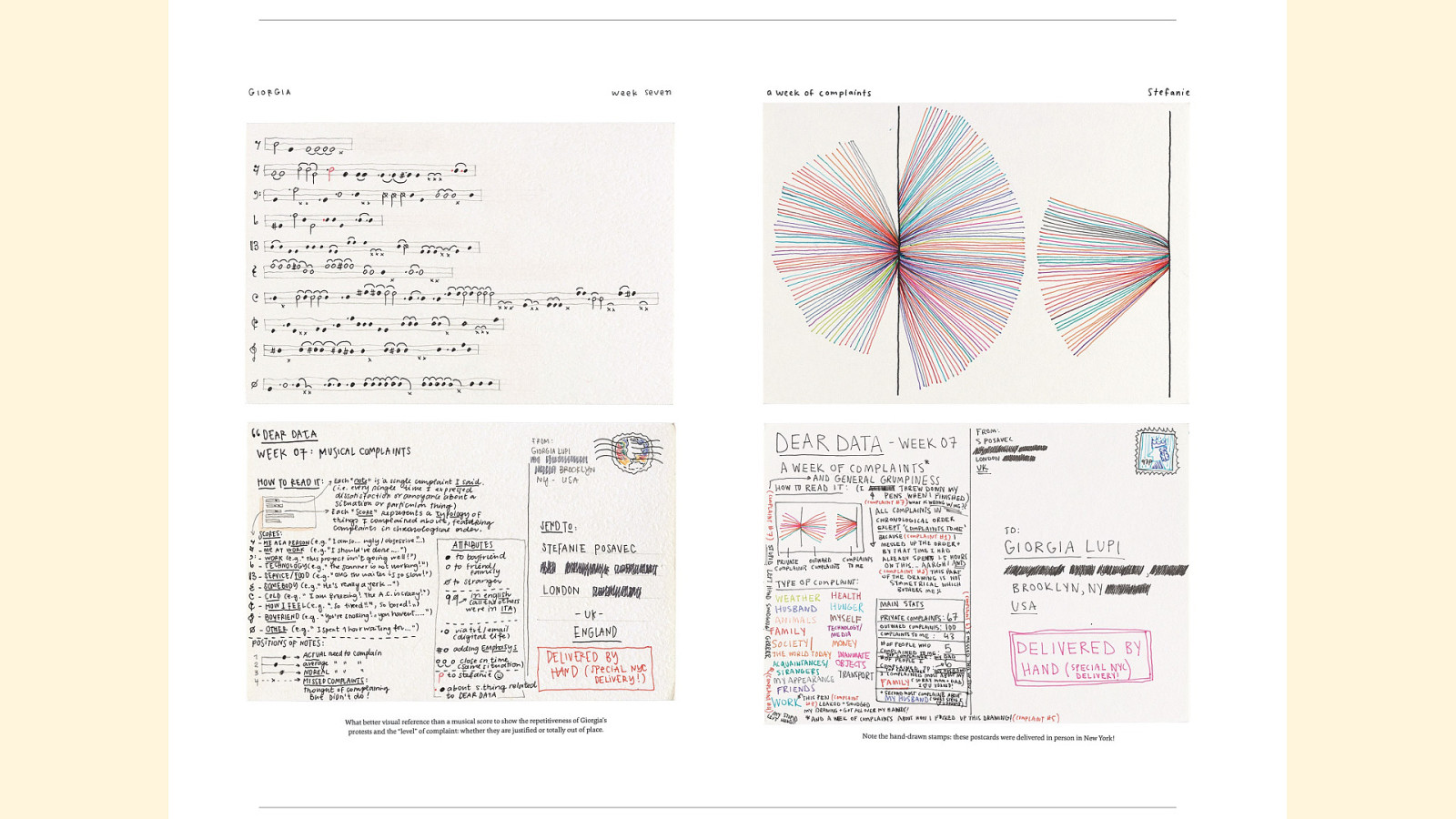

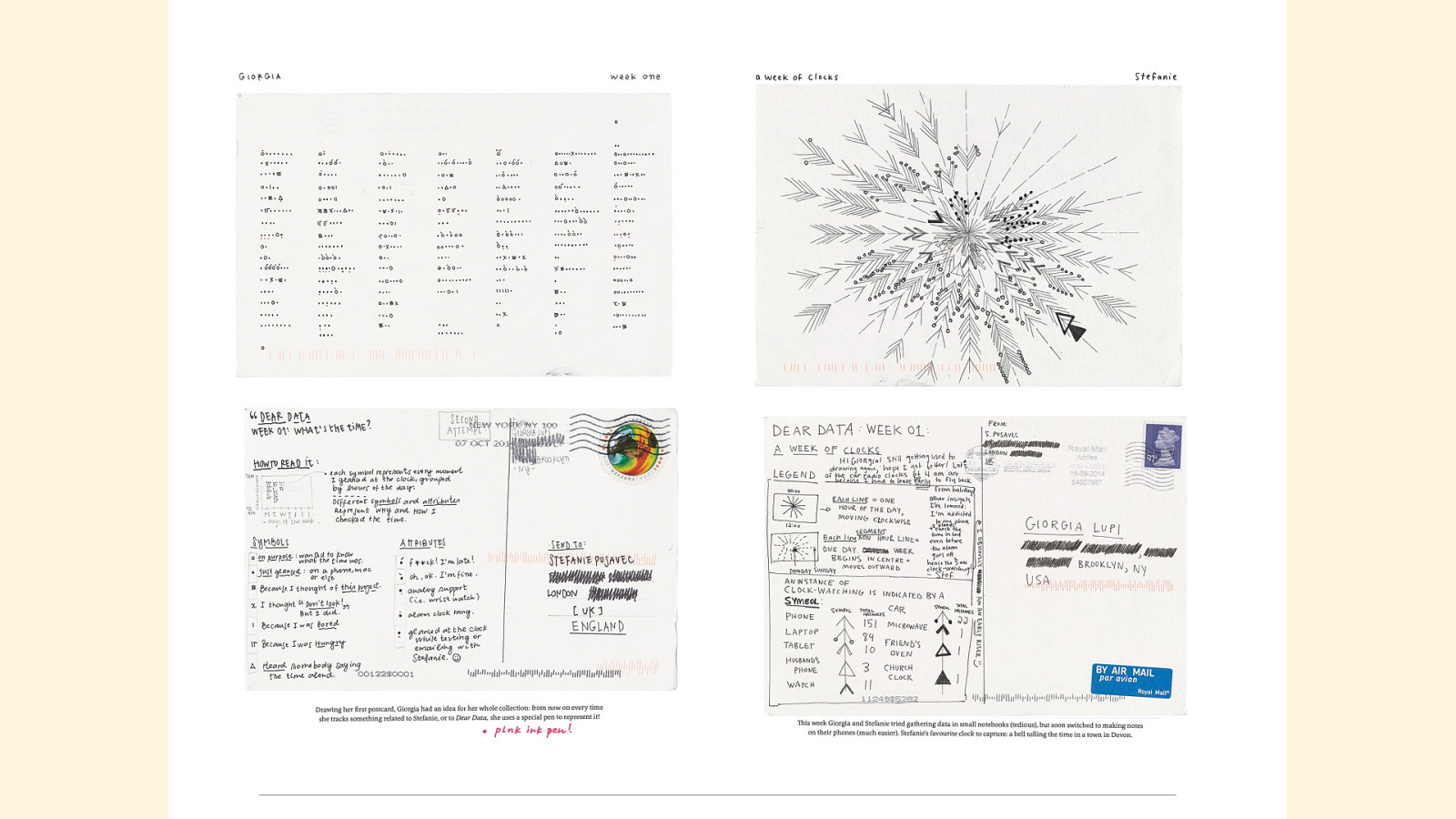

Some of you might already have heard about this project: Dear Data. It is a year long analog data drawing conversation between designers Stefanie Posavec and Giorgia Lupi.

They made small data sets for each week and translated them into beautiful drawings on a postcard. For me this is design research because all the post cards together give so much away from who they are and what their lives are like.

And also: because they show that even such a small data set like ‘all the complaints of this week’ is a little research study in itself.

A year ago I attended a masterclass by Stefanie to learn more about translating data sets into beautiful art data visualisations. There I got to know her work even more. She uses analog dataviz and drawings to better understand data for herself and others.

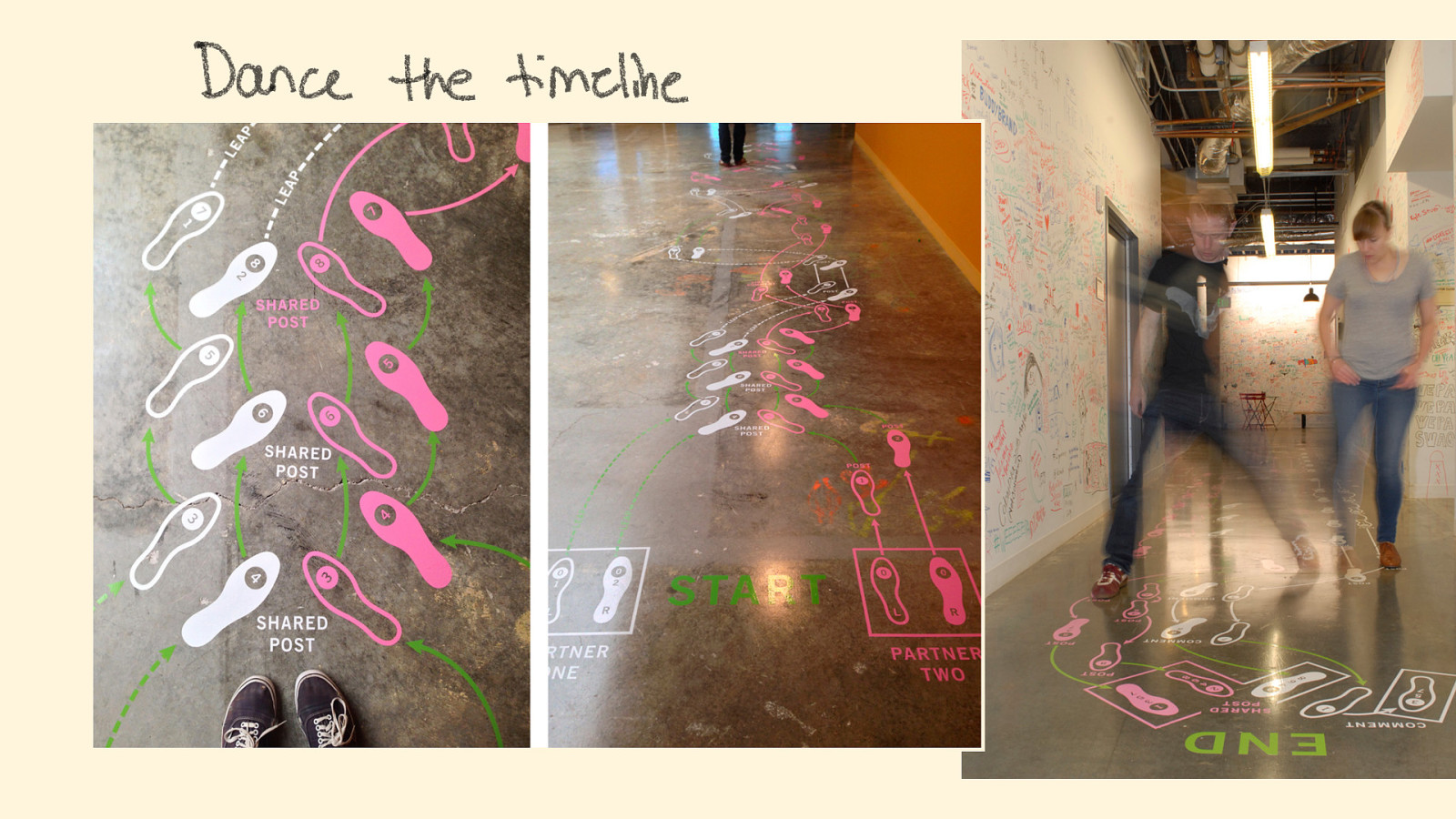

For example when she did an art residency at Facebook and she designed ‘the timeline dance’ to better understand how people engage on Facebook. She converted a month of a couple’s Facebook interaction data into dance steps, referencing how couples often ‘perform’ an orchestrated, public version of their relationship on social media.

About this project: http://www.stefanieposavec.com/facebook-art-residency-relationship-dance-steps

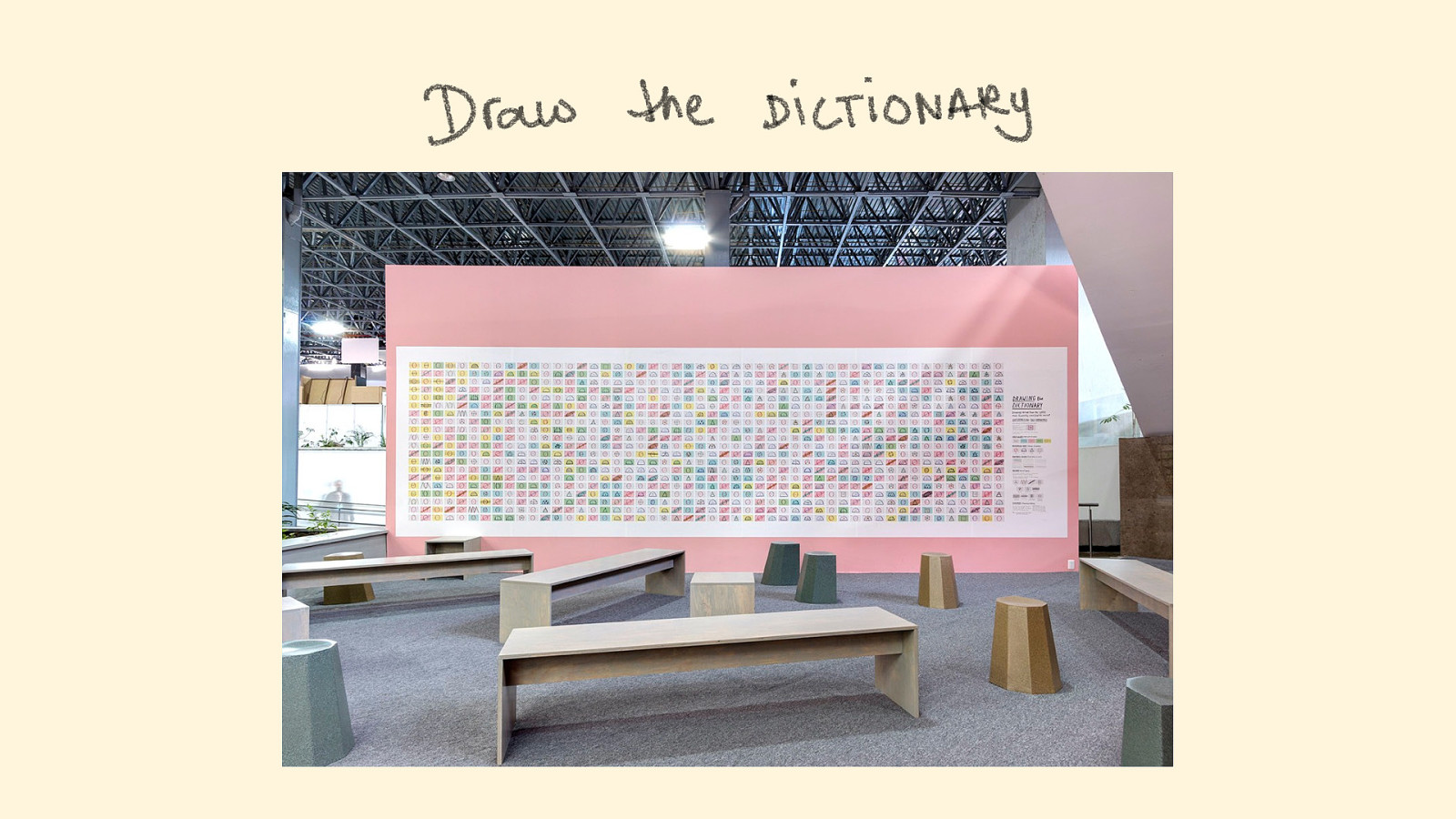

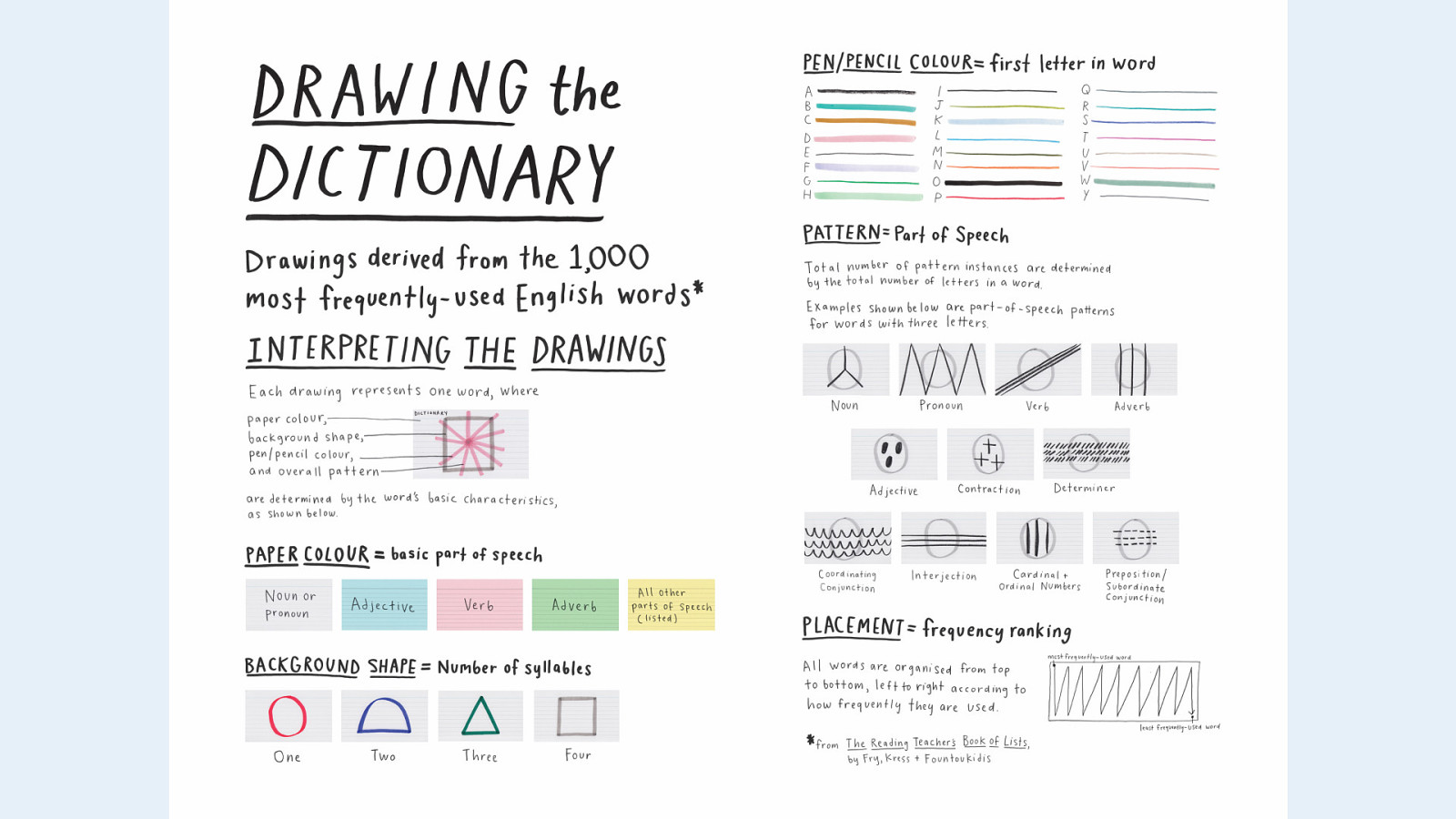

Or the work that she did for the UK Pavilion at Feria Internacional del Libro (an international book fair) in Mexico called Drawing the dictionary. She created a mural comprised of a collection of 1,000 small drawings on index cards.

Each drawing visualises data (part-of-speech, number of syllables, first letter of word, etc.) from one of the 1,000 most frequently-used English words in order to create a multi-coloured mural highlighting the beautiful variation in the English language.

Her mural explains the beautiful variation in the English language on a level that’s per se explicit, but more implicit. You can experience the language wether you’re good at reading or not. You can see it, sense it. Experience the quirks and what more.

I will come back to these projects later to explain them a bit further.

About this project: http://www.stefanieposavec.com/drawing-the-dictionary-1.

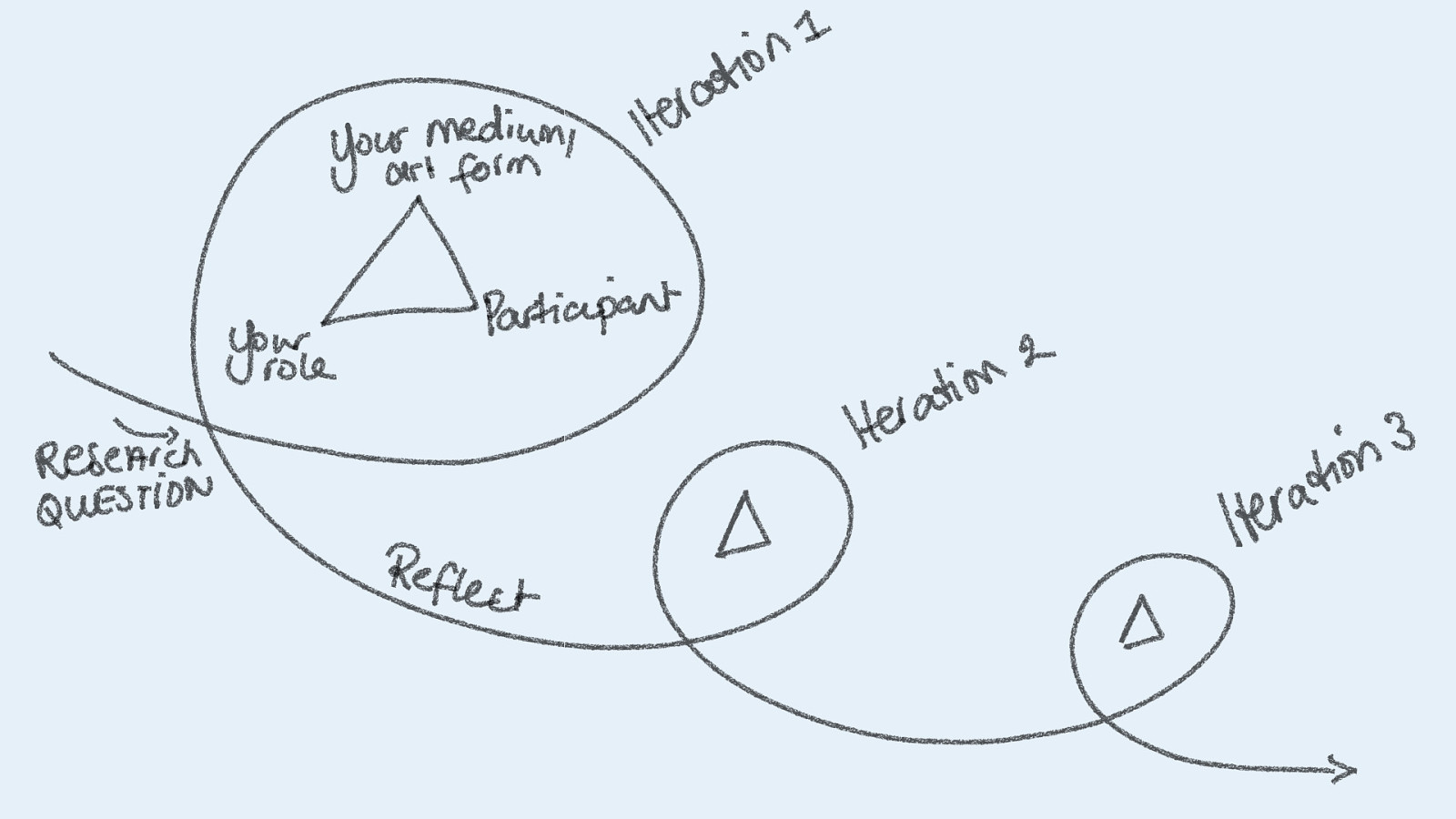

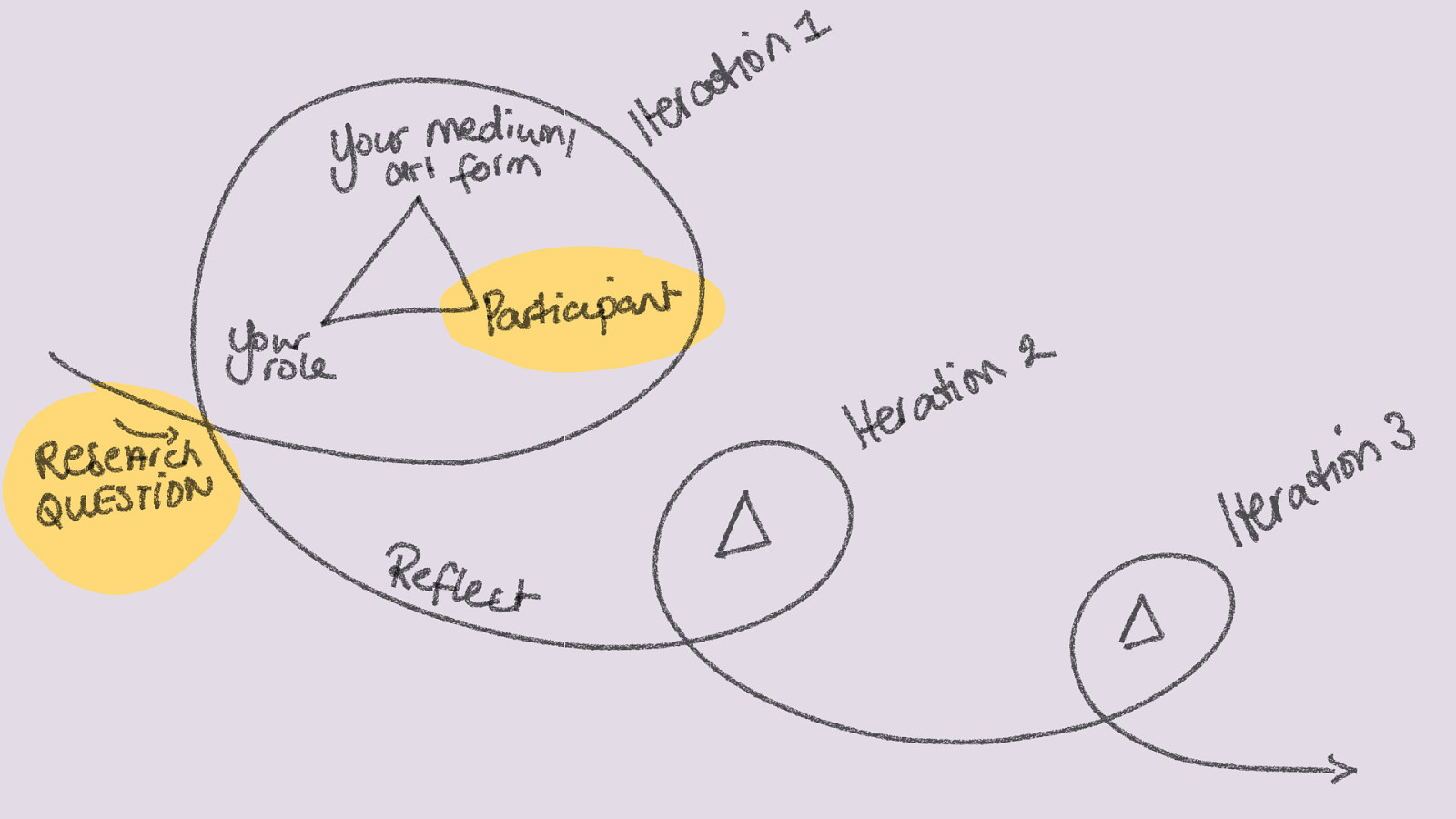

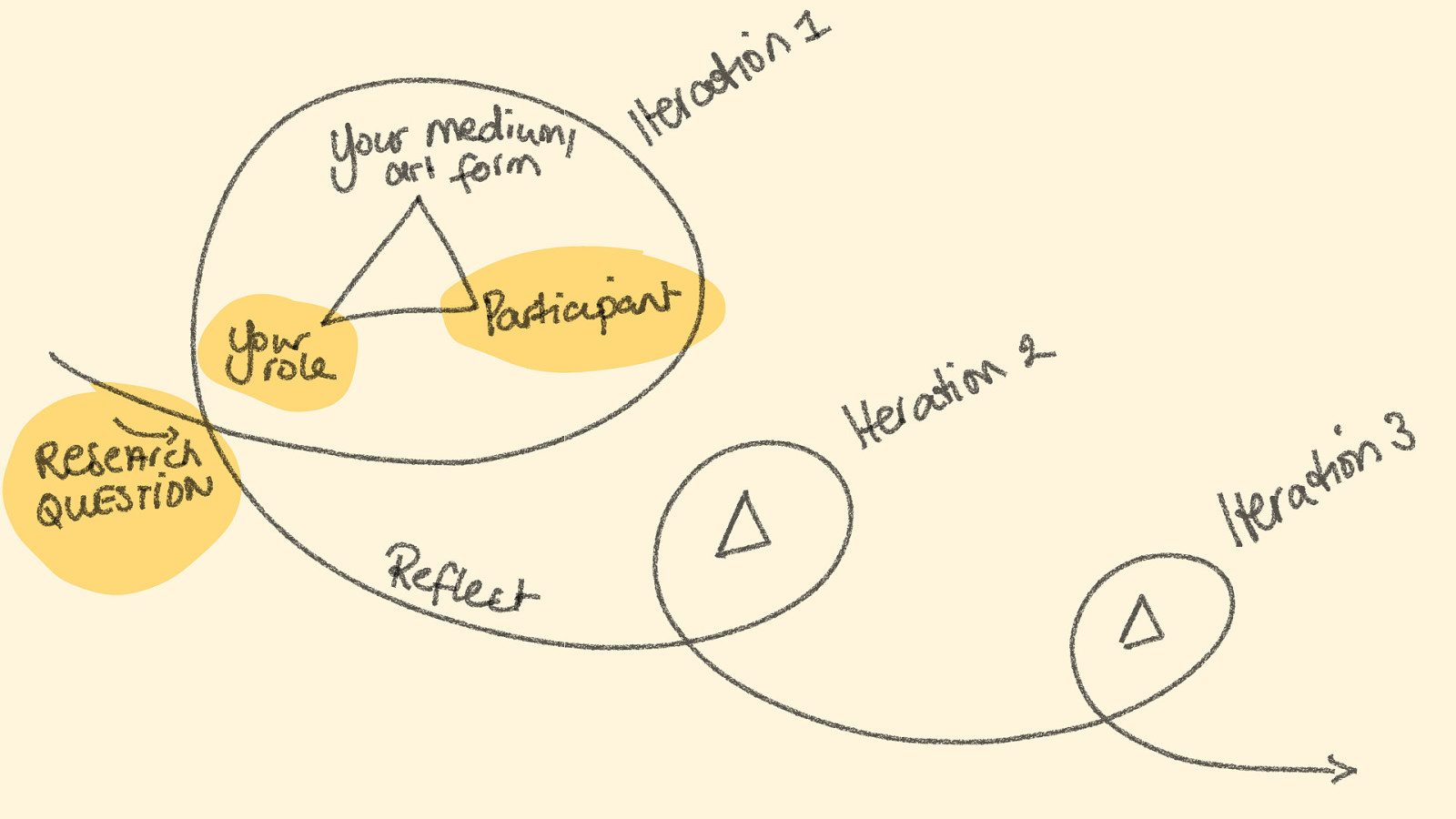

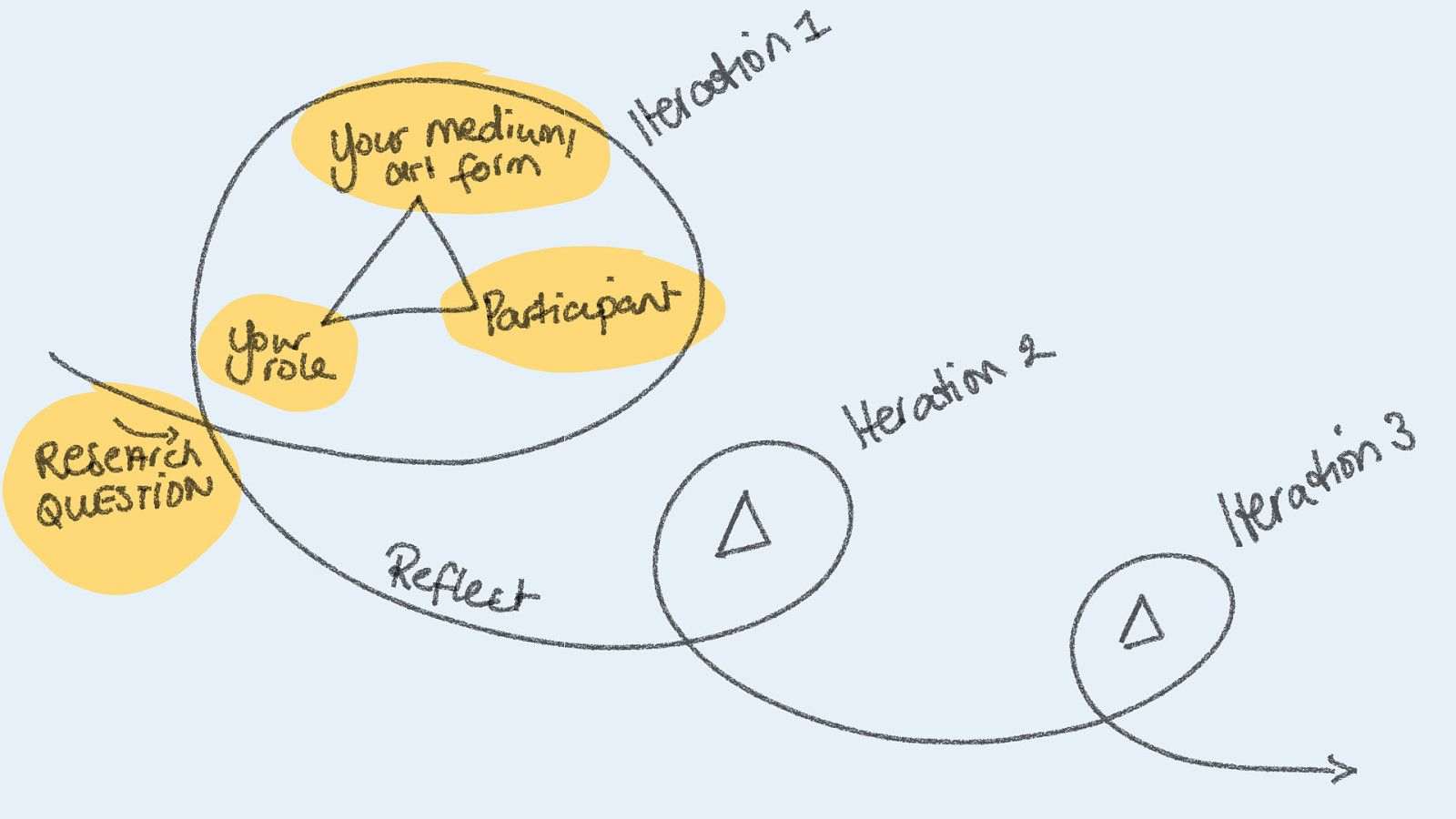

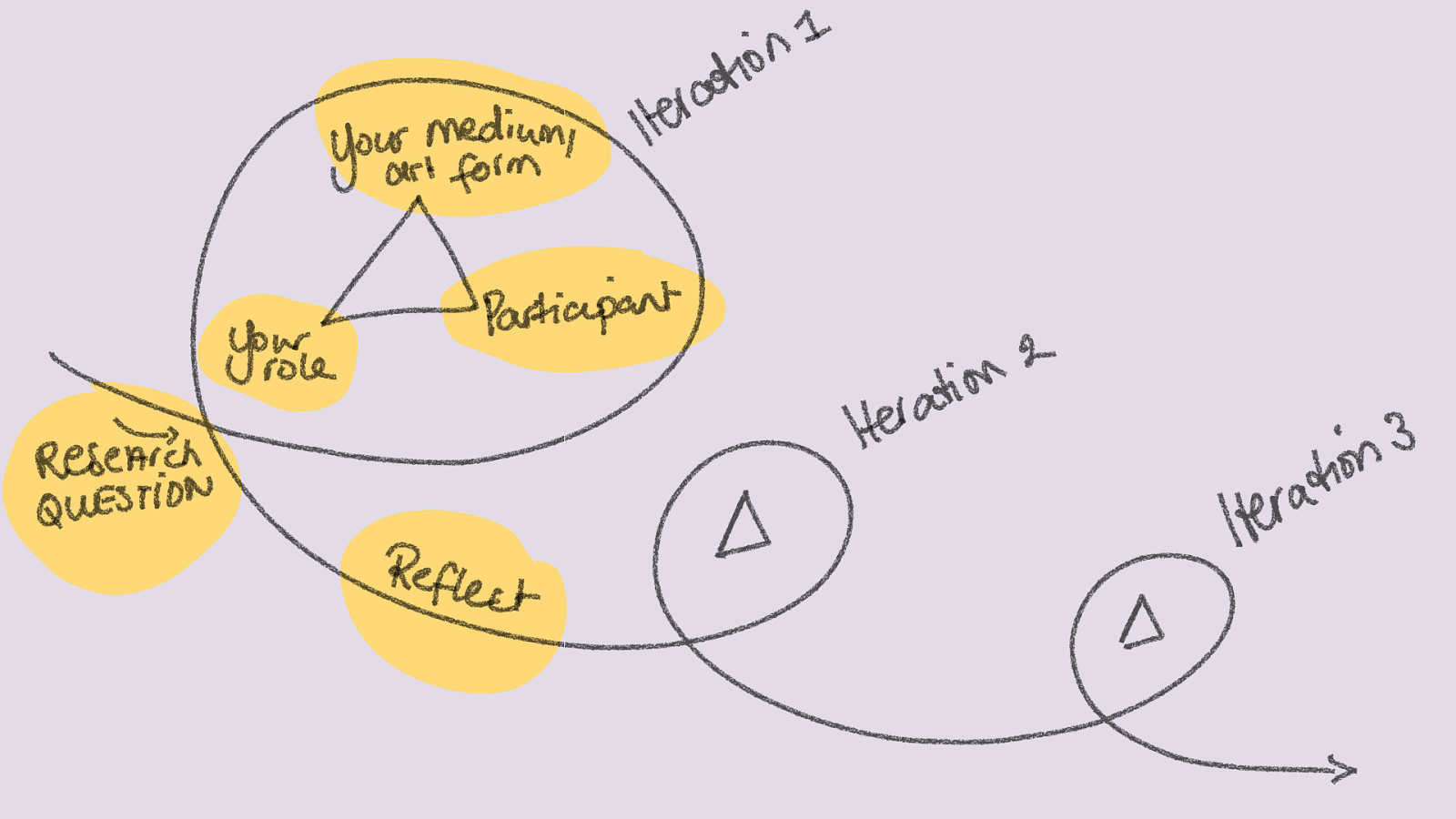

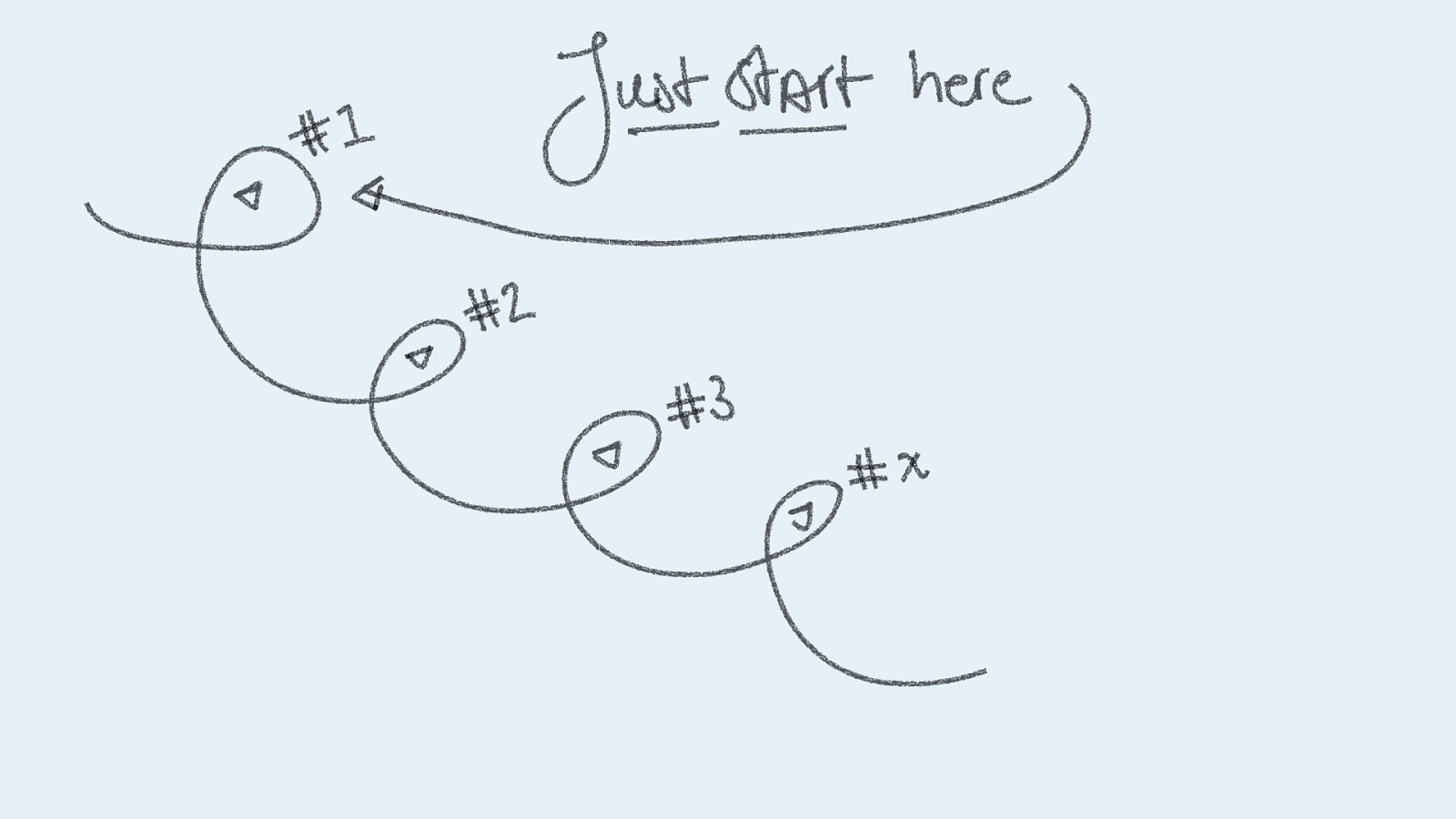

All these methods are designed. They are made to do research and to find out how things are. That’s not something that happens overnight. It is design and as we all know design happens by trying it out and iterating a lot!

But how do you start designing your first iteration? Your first encounter, the first felt, the first dance, drawing, or the first photograph?

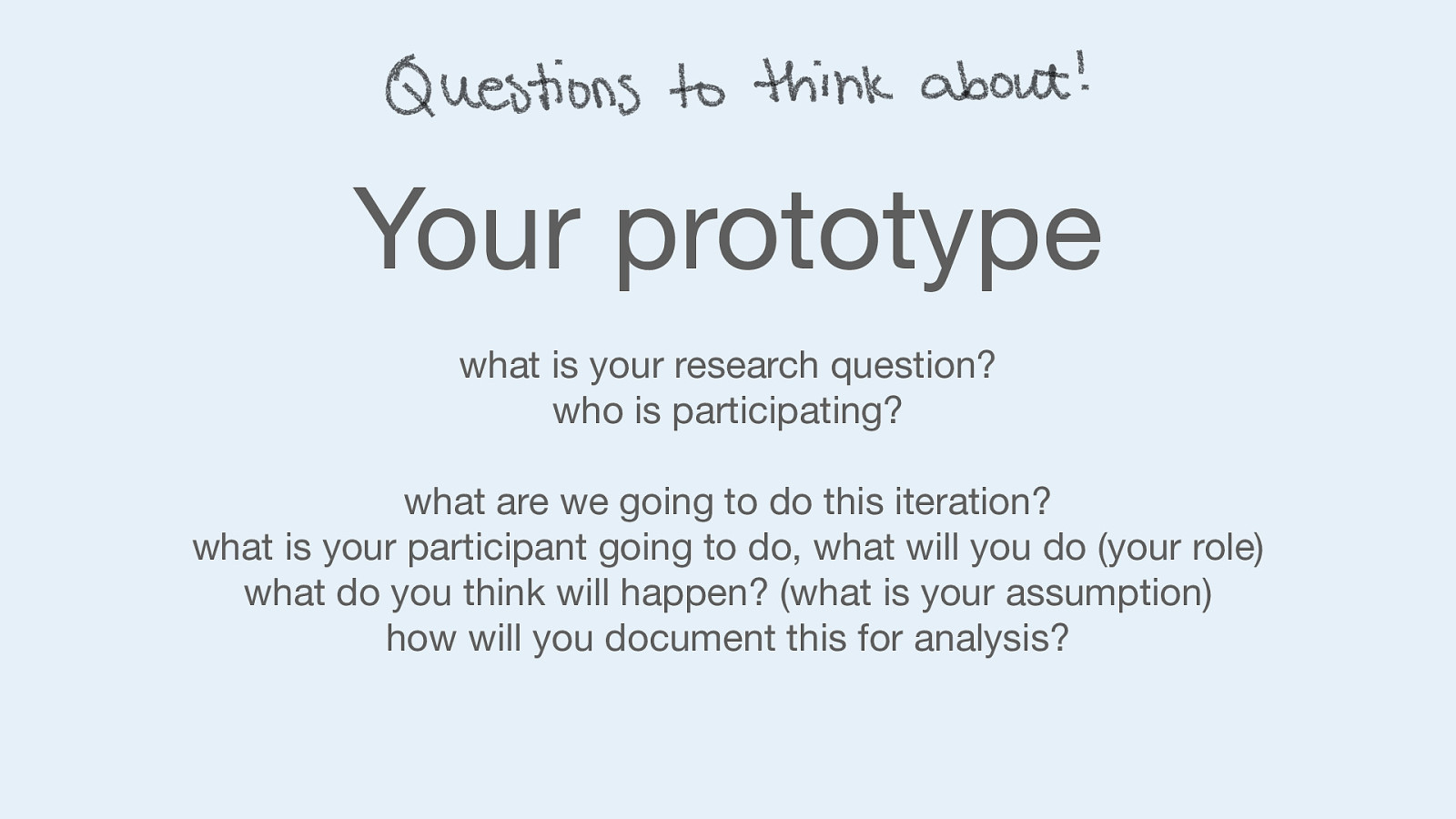

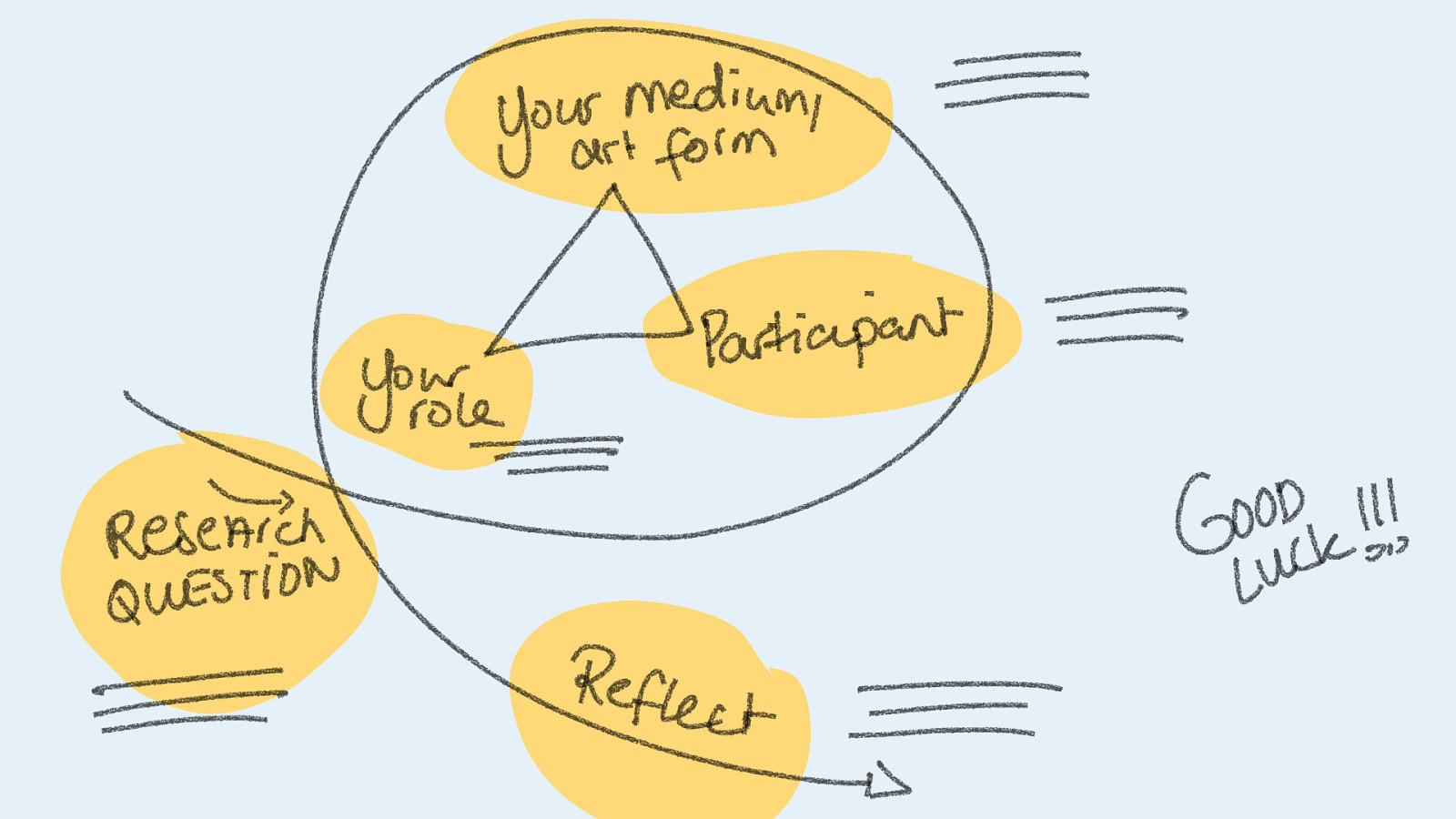

When designing an iteration you have to think about a few aspects.

And after the iteration you have to reflect on the outcomes so you can adjust your strategy before doing a second iteration.

Today I will take you through these steps.

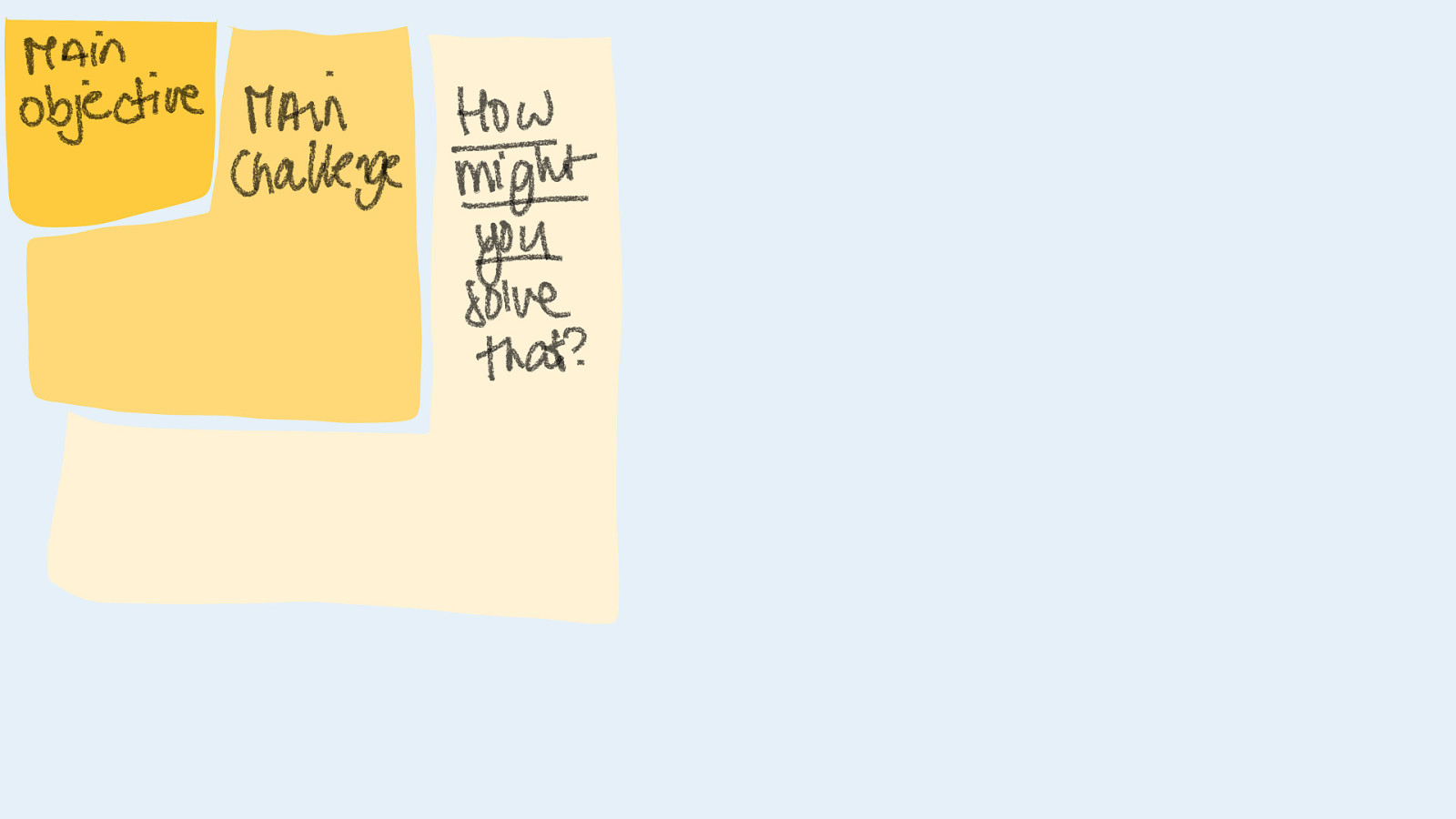

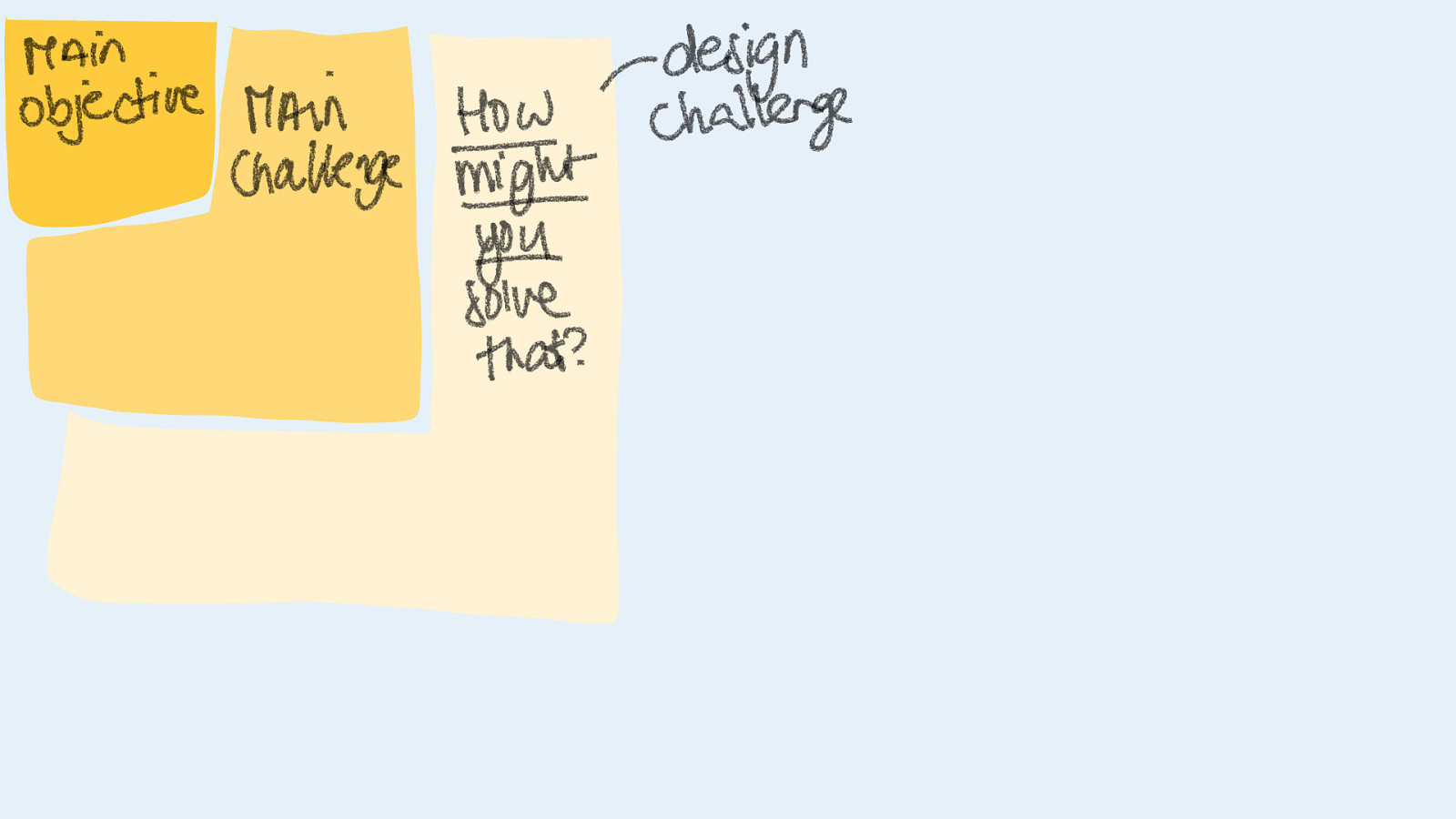

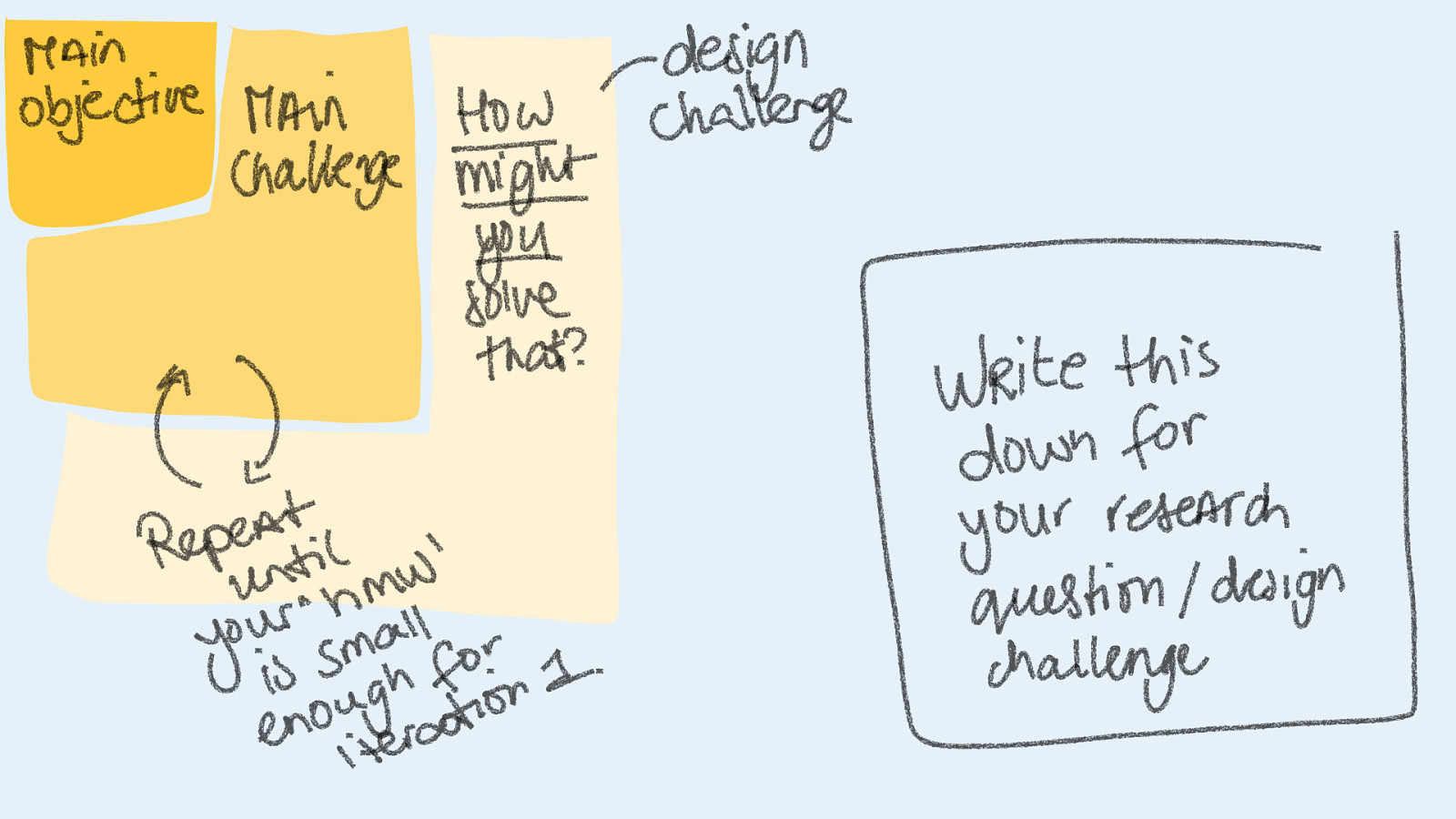

We start with the research question. I already mentioned that to me questions are like finding a path in unknown territory. Our main objective is to reach our goal, but most of the time we have a very vague idea of what that goal is. It’s time to think this through and to understand our questions.

I always start by writing down what my main objective is.

Then I write down my biggest challenge.

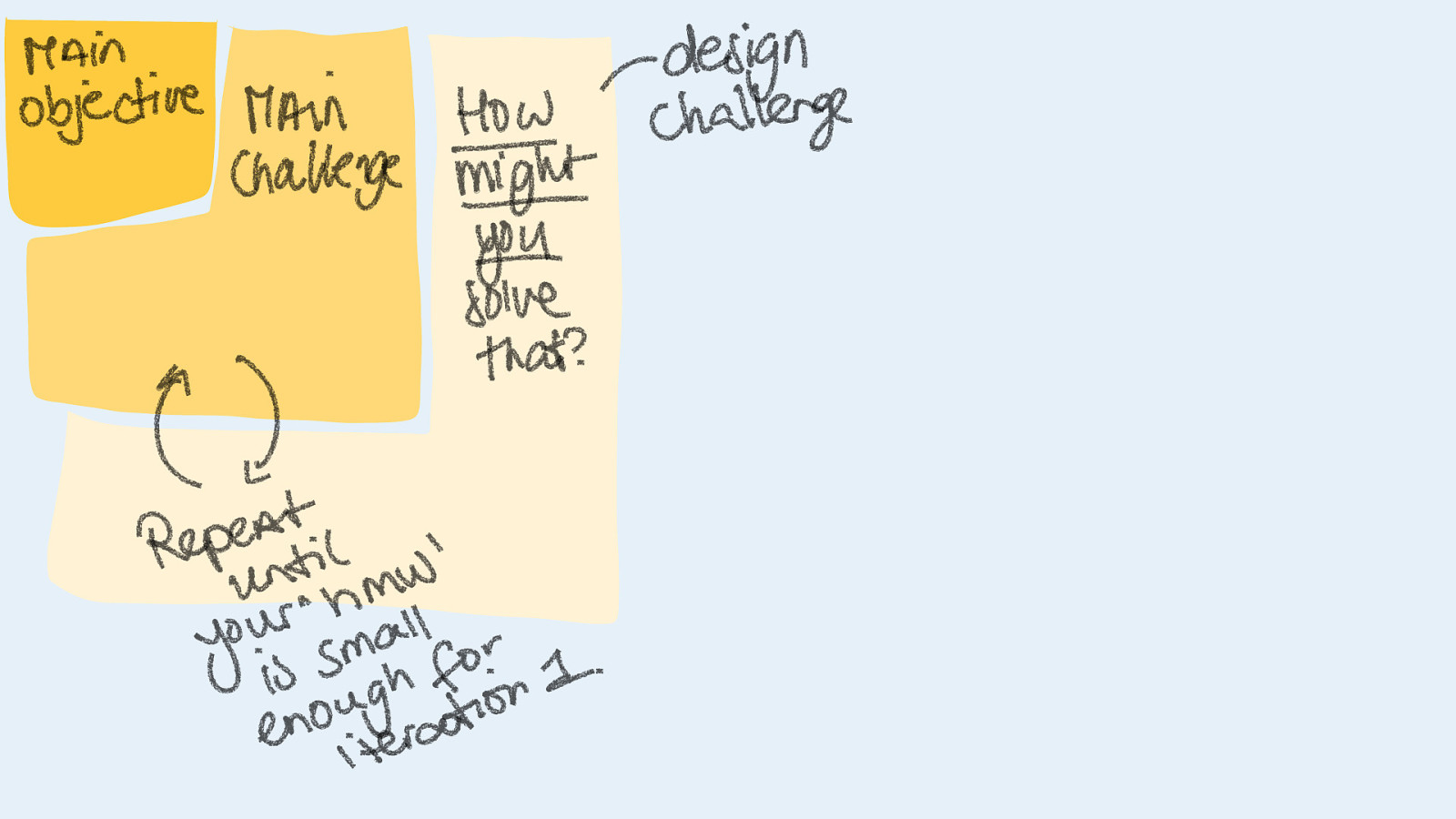

I ask myself how might I solve that challenge?

I write my questions starting with ‘how might we’ because that helps to start the designing process.

You can repeat these steps and every time you do this your design challenge will become smaller and more concrete.

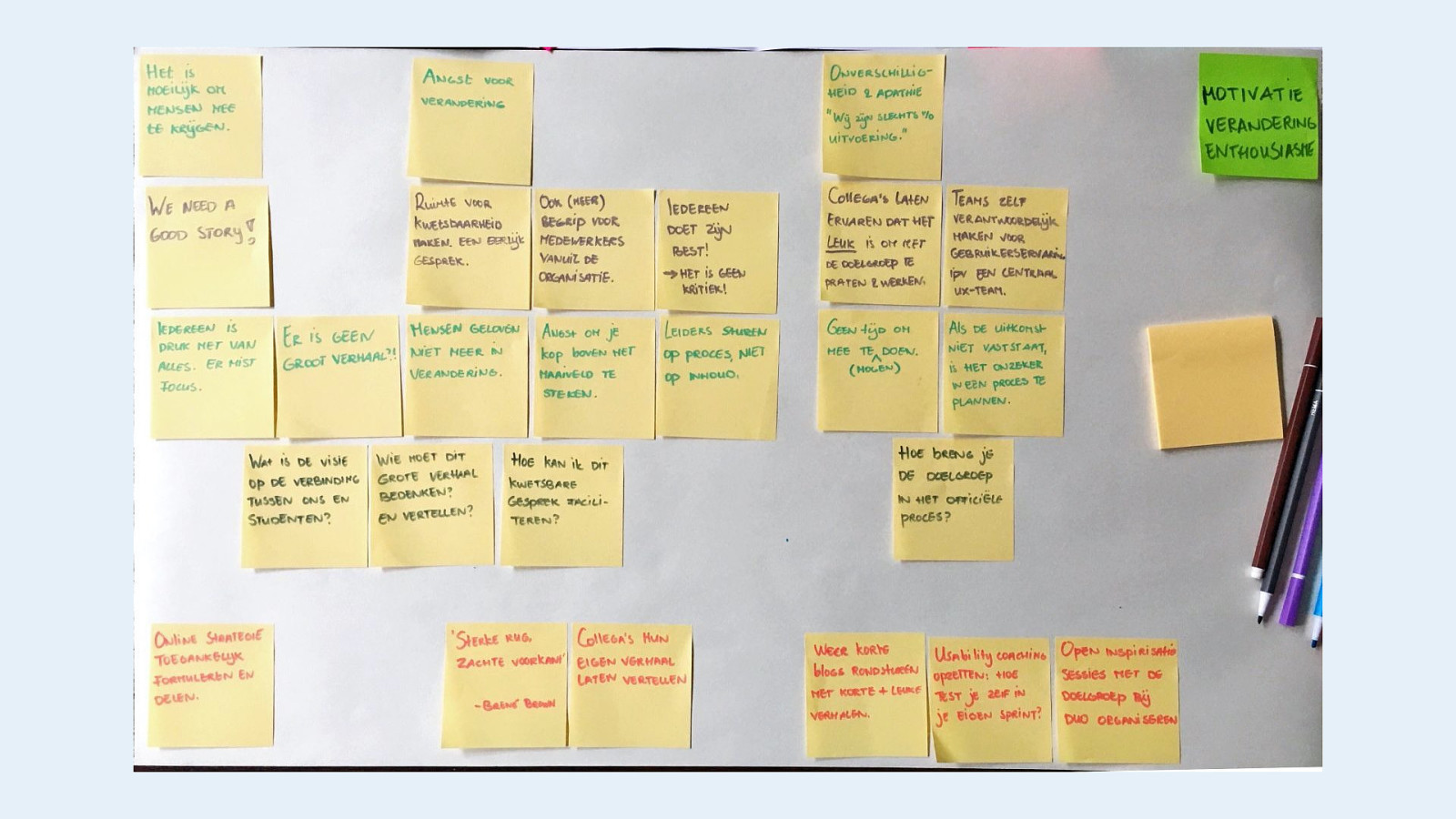

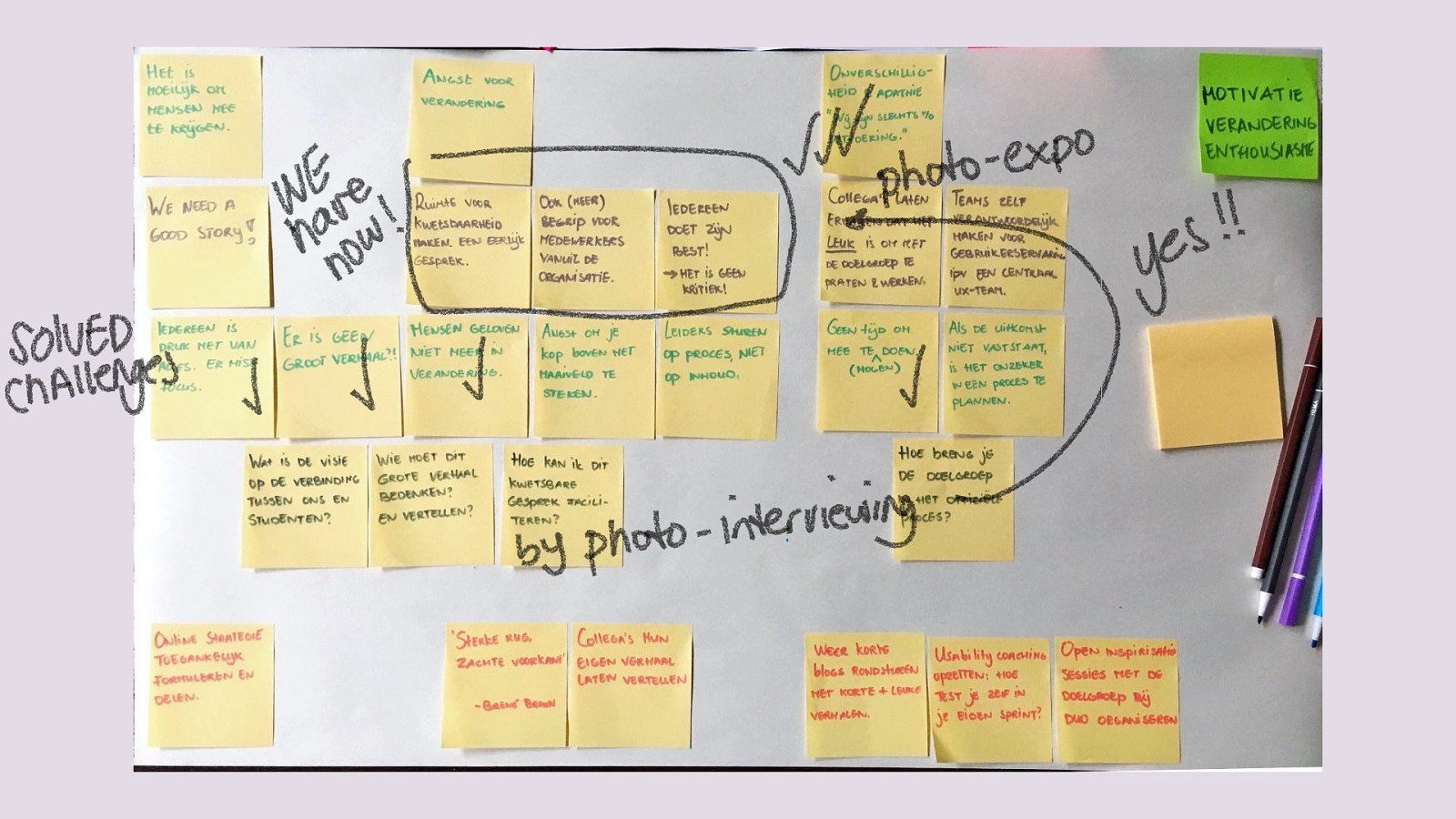

I did this exercise and ended up with a wall of post-its. I hang them up in my studio so I saw them everyday and they helped me to design my iterations.

I started with my main challenge: how to have a compassionate digital government. One of the challenges (I had 5 of these post-it boards) was ‘it’s hard to get people motivated to join my quest’. Then I wrote a solution would be if we had a good story. But then… there isn’t one I thought. Everybody is so busy, people don’t believe in change anymore. They are scared to speak up.

Then I wrote ‘How might I facilitate this conversation? How can I help other civil servants to tell their part of the story?’

Read more about this step on my research blog: https://klipklaar.nl/een-veranderende-organisatie/de-strategietaart-uitgewerkt/

A ‘How might we’ question is ideally to start designing a design research iteration.

Let’s try it. What is your main objective? And what is your first challenge? Let’s take a couple minutes and try to make your main objective into a design question that we can turn into a first iteration.

That was the first step of designing our art-based research method.

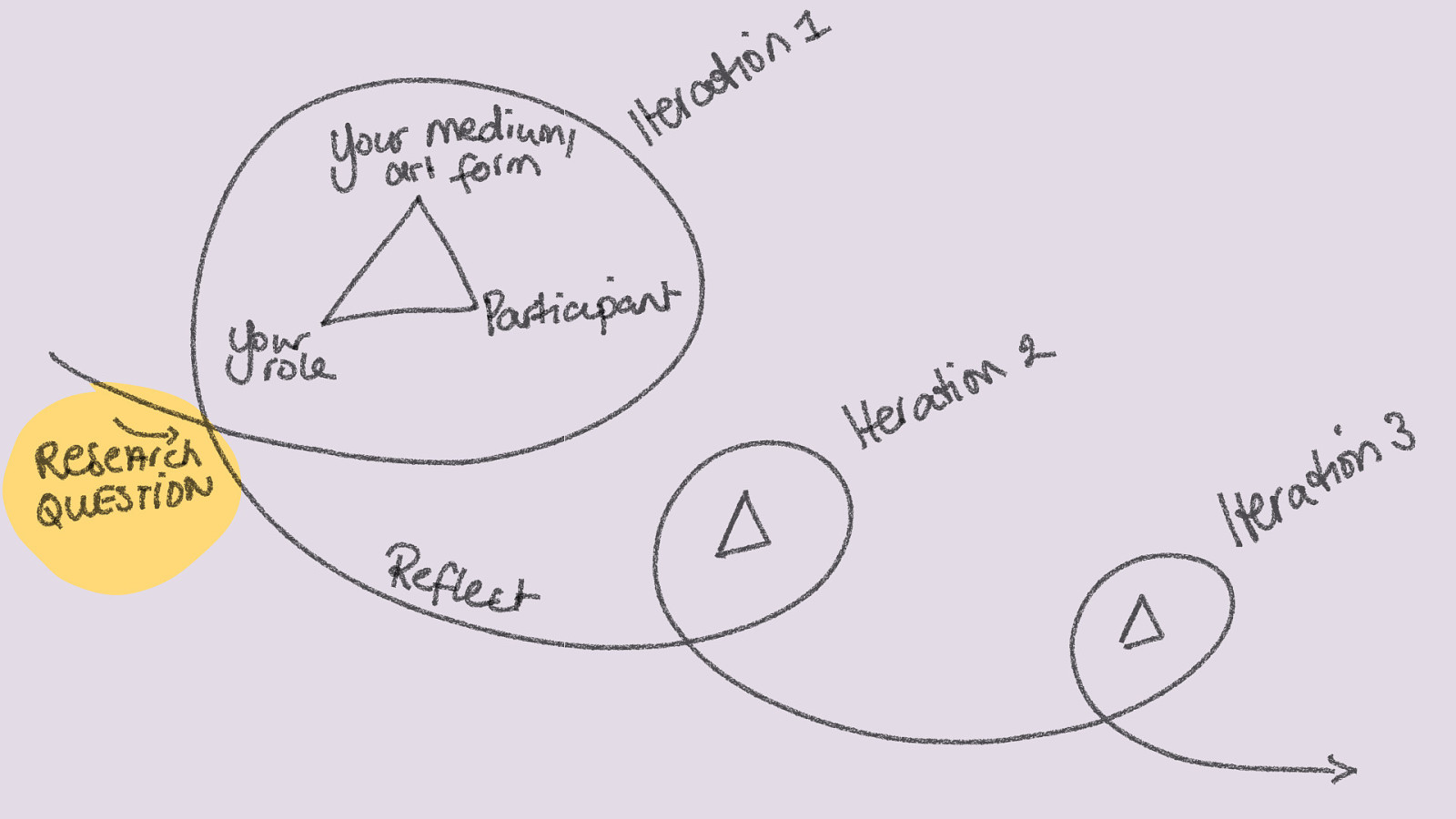

The next thing we’re going to focus on are our participants.

As a UX researcher I was used to have an expert mindset. Me, the usability researcher in the UX lab, interviewing and observing users as they use a website.

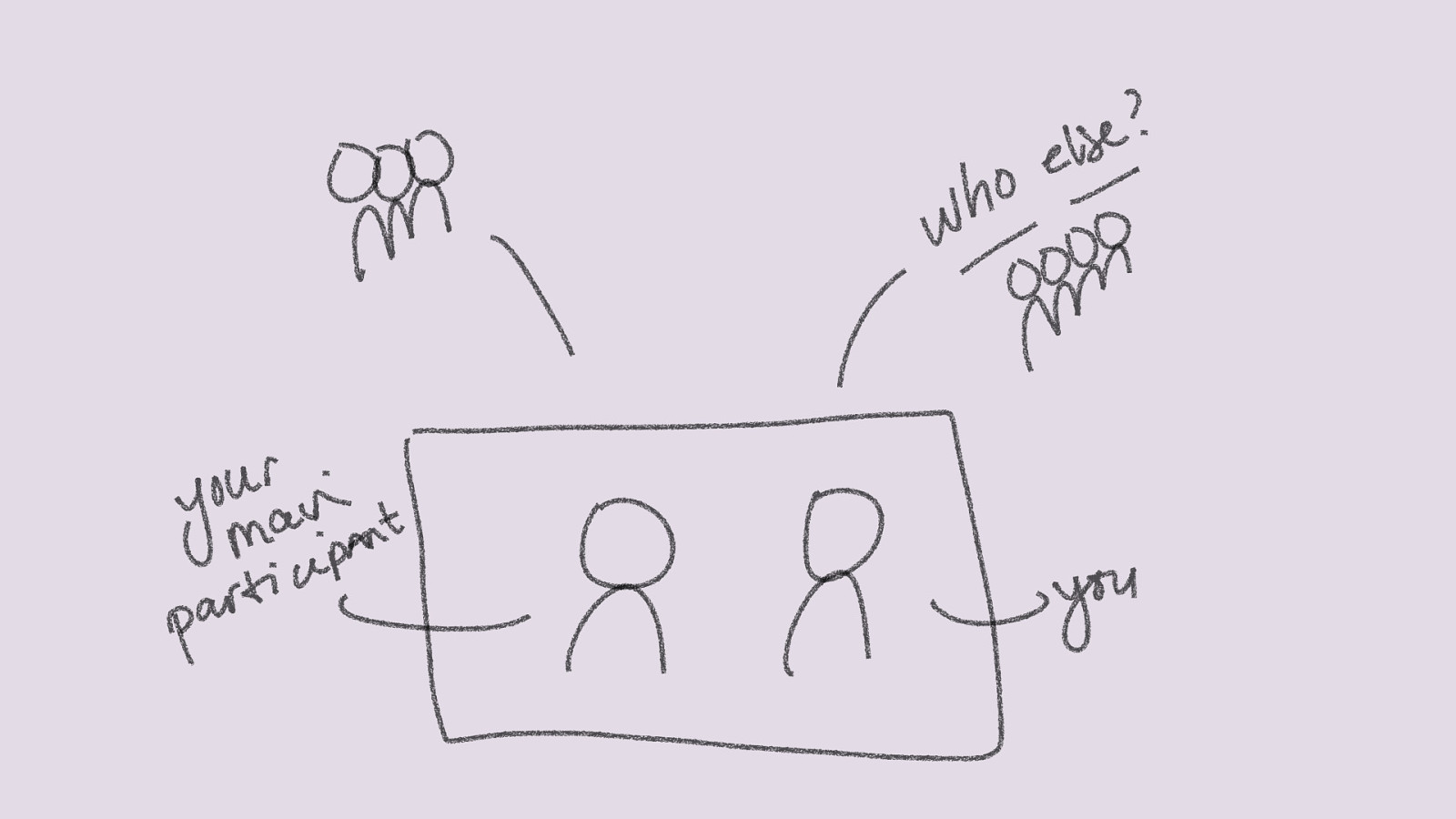

In design research it takes another mindset. Users aren’t reactive subjects, but are equals. They are active contributors and we see them as partners. Users are not the only participants that you might have in your research. Participants can be stakeholders as well. It is everyone that is involved in your research question in one way or another. They don’t have to be a part of every iteration by the way.

This model is from the Convivial Toolbox, a great book about generative research.

In Encounter there are different participants who each have a different role. We have, of course, the main participant. The person with the scar. We have Joost, the designer. I see a host, who is also documenting what is happening (great!). We have the lady busy with the embroidery. We have some people watching.

And there are also the people we don’t see here. Care workers, doctors, hospital staff, academic partners and others funding this art project. They are not part of the encounter with patients, but Joost designs other iterations to involve them in his design research.

Participants and stakeholders can be in the same group or in the same iteration, but they don’t have to be.

In my own research Jean and the other portrayed colleagues are the most visible participants. But there are a lot more participants. Other colleagues or people working in government who read my blog are participants as well. My boss, who is part of the research question about a compassionate digital government, but who is also responsible for the status quo and/or change that this research project have been challenged/ sparked. Sometimes participants can have multiple roles.

Read more about how I selected my participants on my research blog: https://klipklaar.nl/een-veranderende-organisatie/ruimte-voor-begrip-in-de-weg-van-wet-naar-digitaal-loket/

Who are the participants that you are engaging with? Write some of them down. It’s okay if you don’t know all of them at the beginning. They will reveil themselves along the way.

Let’s meet them. Who wants to share what they wrote down?

In your first iteration, try focussing on 1 (group of) participant(s). You can’t research or challenge them all in the first iteration. Make it small.

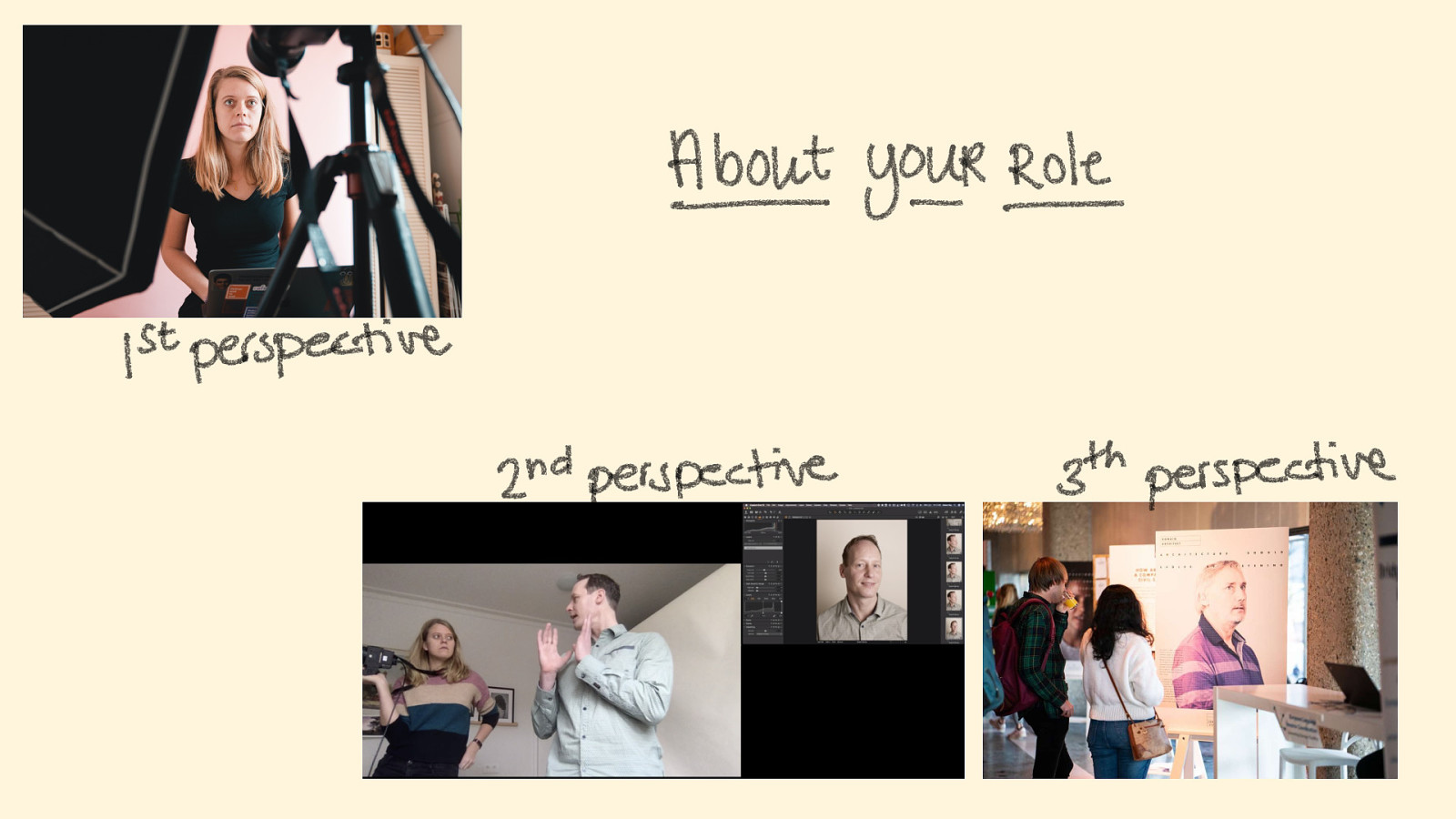

We’ve got participants, but we also need to talk about ourselves. What is our role going to be in the iteration?

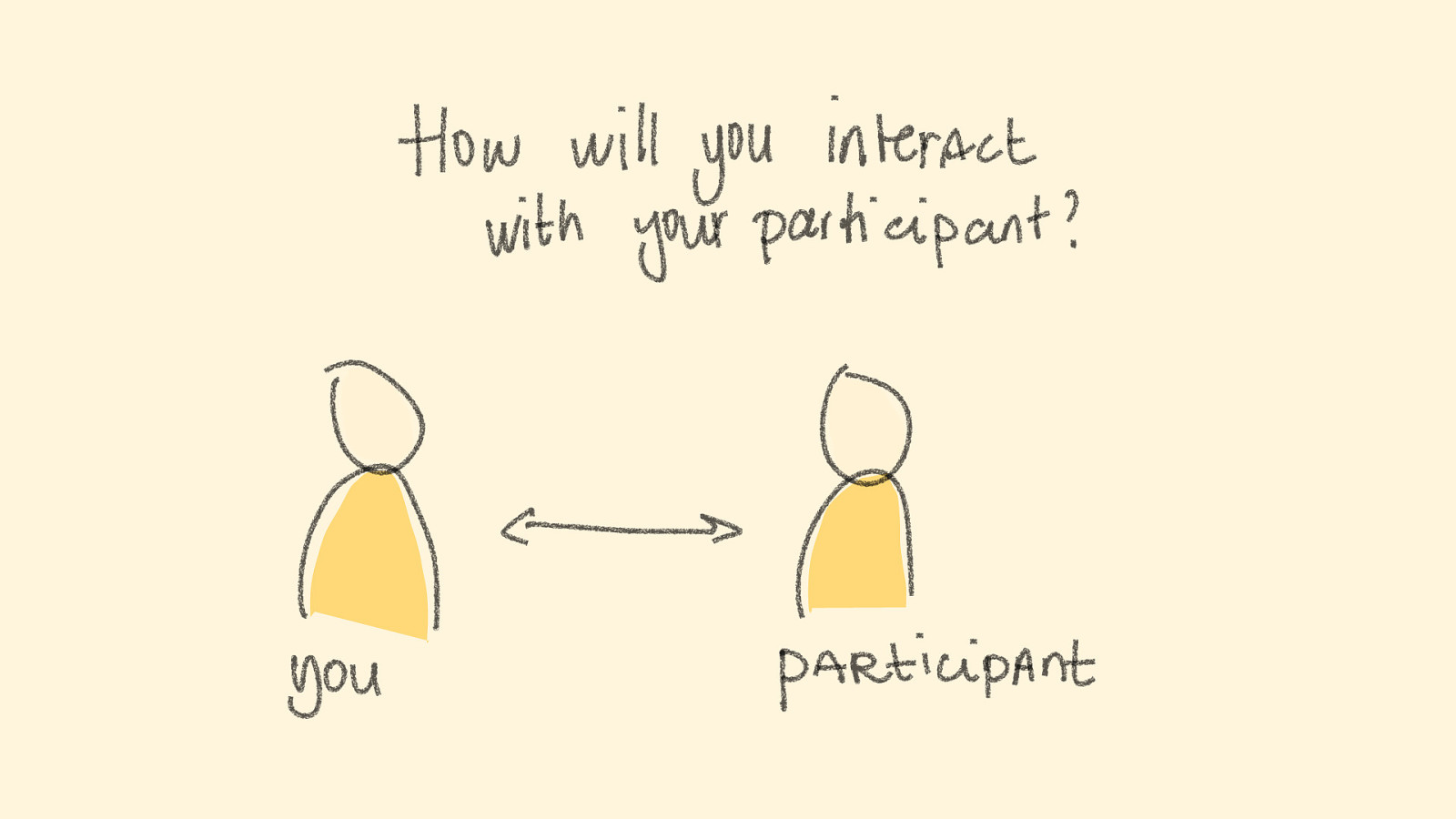

You can have 3 ways of interacting. We call this: first perspective, second and third. I’ll explain with my own research.

First perspective was when I made my own portrait. I wanted to experience myself what others are experiencing. How is the confrontation to translate your ethics, your beliefs, your way of thinking in to a portrait of yourself?

The second perspective is when I, as the photographer, help the participant to portray himself. I facilitate, ask questions, propose images, but Rob (in this case) is the one reflecting and deciding on the portrait.

Third perspective is when I’m not even there to facilitate or to experience. The whole iteration is working by itself. All the participants have roles, but are not dependable on me. I don’t take part, but I am the designer of the whole setting. I have thought everything through and I will be the one reflecting on what happened. It’s when I made a photo-exhibition of all the portraits.

Read more about this step on my research blog: https://klipklaar.nl/begripvolle-ambtenaren/foto-interviewen-als-researchmethode/

When Cora does a felt scape she starts out in the first perspective. She makes she felt scape by studying the land and becoming one with it by felting it.

She uses the outcome (the Feltscape) to have a farmers dialogue with other participants. Her role in this dialogue is from the 2nd perspective.

How will you interact with your participants? What role fits with your research question? With your participants? You can mix and match, and it may differ per iteration.

But of course it all depends on the medium of your choice. The art form that feels familiar to you and that you know by heart.

When I started this project I was already a photographer. I know how photography works. How to make a portrait, to position the lights, to make the picture at the right moment and I knew the techniques of tethered shooting, for example. Photography is my art. And I am my art.

Stefanie knows how to draw and makes beautiful analog graphical art works. Cora already knew the art of felting before she started using this in her farmers dialogues. Joost has been a costume designer for years before he started Encounter. These designers take their experience and art with them into their research projects. This is key.

This expertise is what you need to know how to use your art in a research project. But that’s not the only reason why it works.

You also have to experiment. It doesn’t come to you all rational. You have to make to think. Do to design.

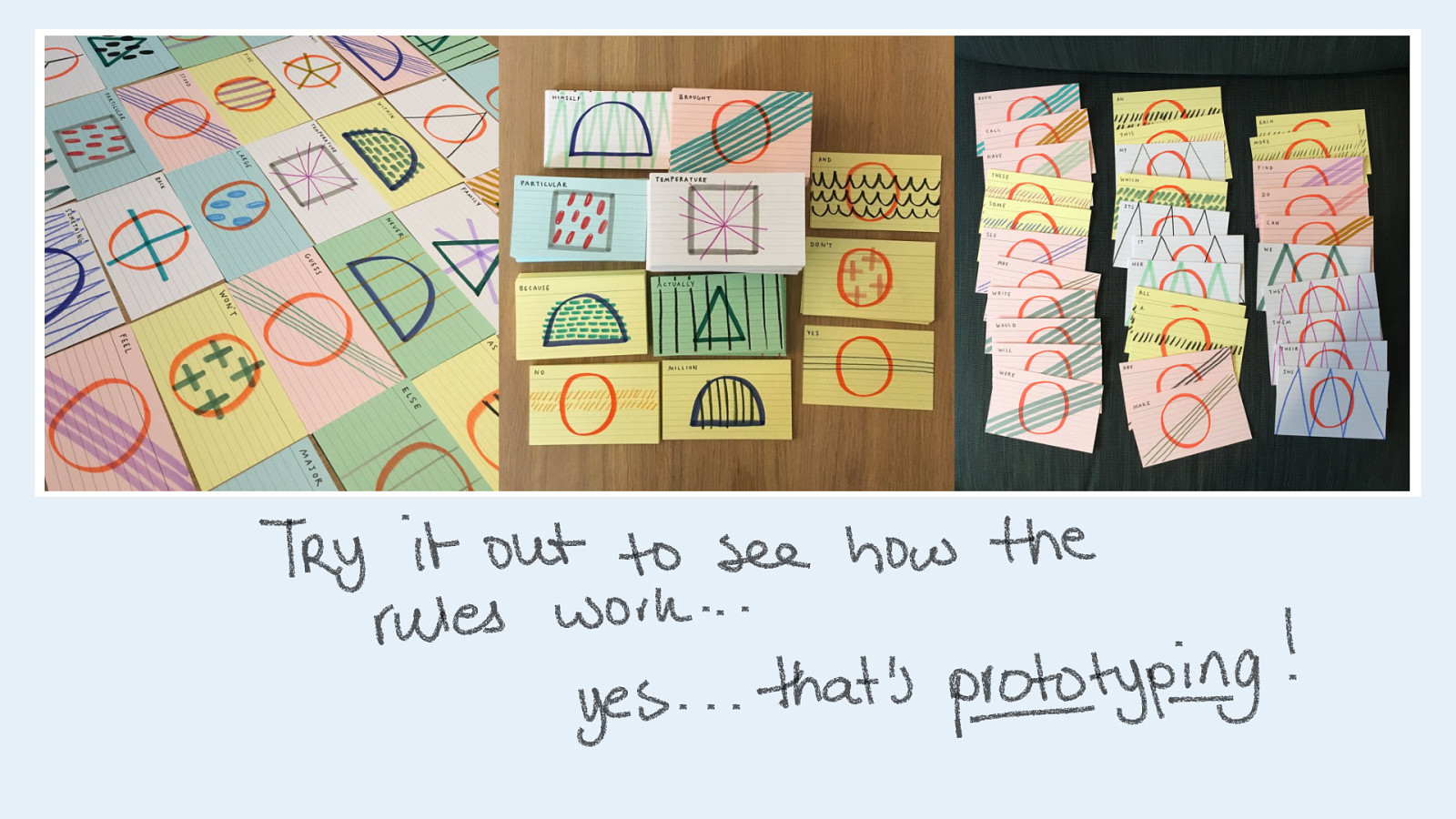

Make a prototype, try it out and learn from it. You can prototype your art-based research project. That means setting up rules how you are going to use it.

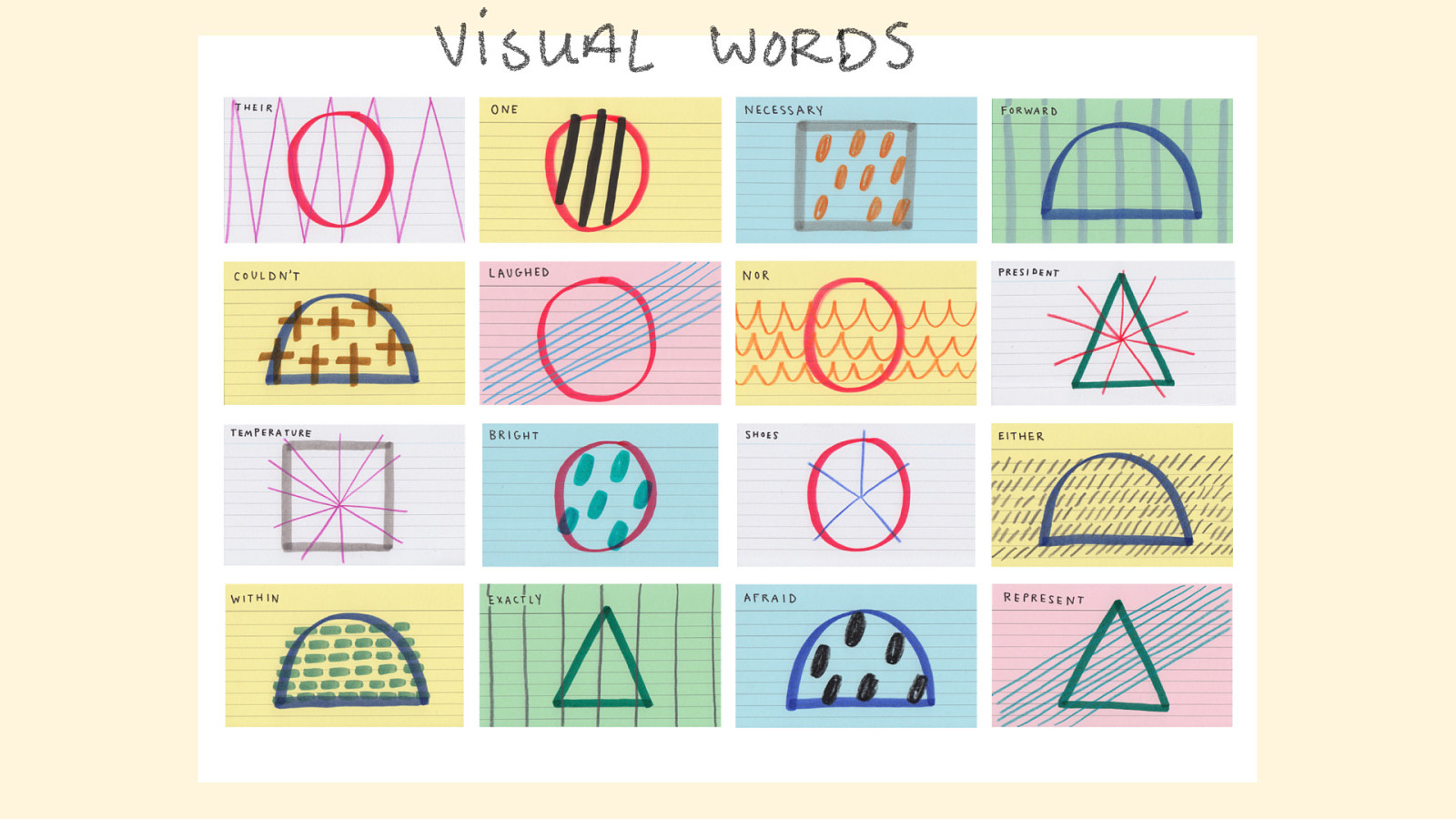

I mentioned Stefanie’s work and I love how she prototypes. By experimenting she comes up with a set of rules. These are the rules for ‘Drawing the dictionary’.

These rules aren’t pre-thought of but they are designed by experimentation. She tries them out to see how they fit and ultimately the data, the research itself, defines the real outcome.

That means prototyping your iteration and testing, testing, testing. I love how she did that at the facebook timeline dance I mentioned earlier.

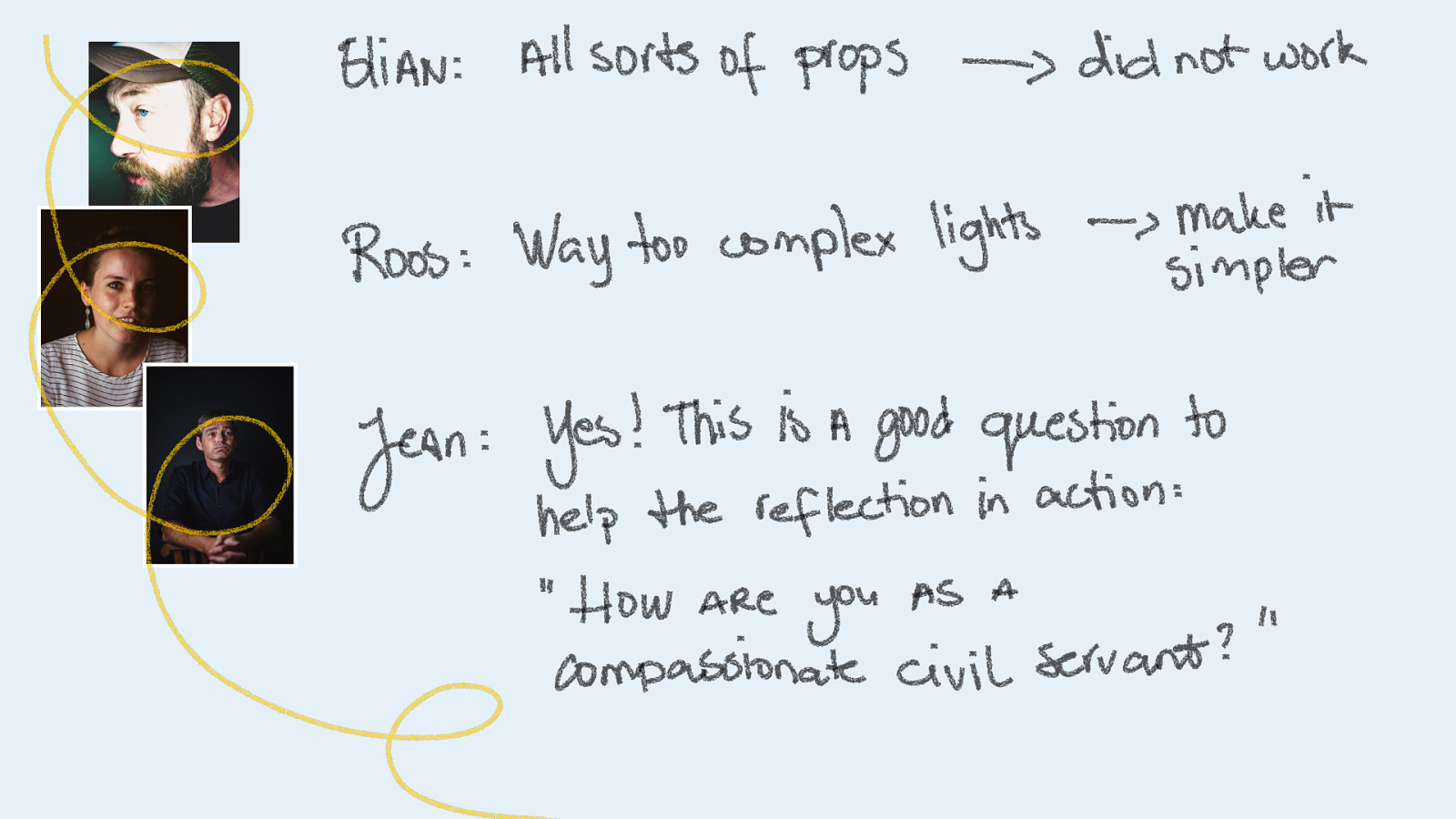

Before I had a clear set-up of the photo-interview I tried out a lot of different things that didn’t make it in the designed experience after all. For example I bought these white masks for participants to ‘draw their mask as a compassionate civil servant’. Or I had paper and pens, to help them associate by drawing. Or a wooden figure to help them find a posture. I had different colours of lights that participants could choose. All these props didn’t work in the experiments. They added noice and in the end I made it more simpler.

I experimented on myself and on my friends and colleagues. This helped me to see how they reacted to the set-up. It’s a great way to perfection your research prototype. And along the way it get’s better.

Read more on these first experiments on my blog: https://klipklaar.nl/begripvolle-ambtenaren/foto-interviewen-als-researchmethode/

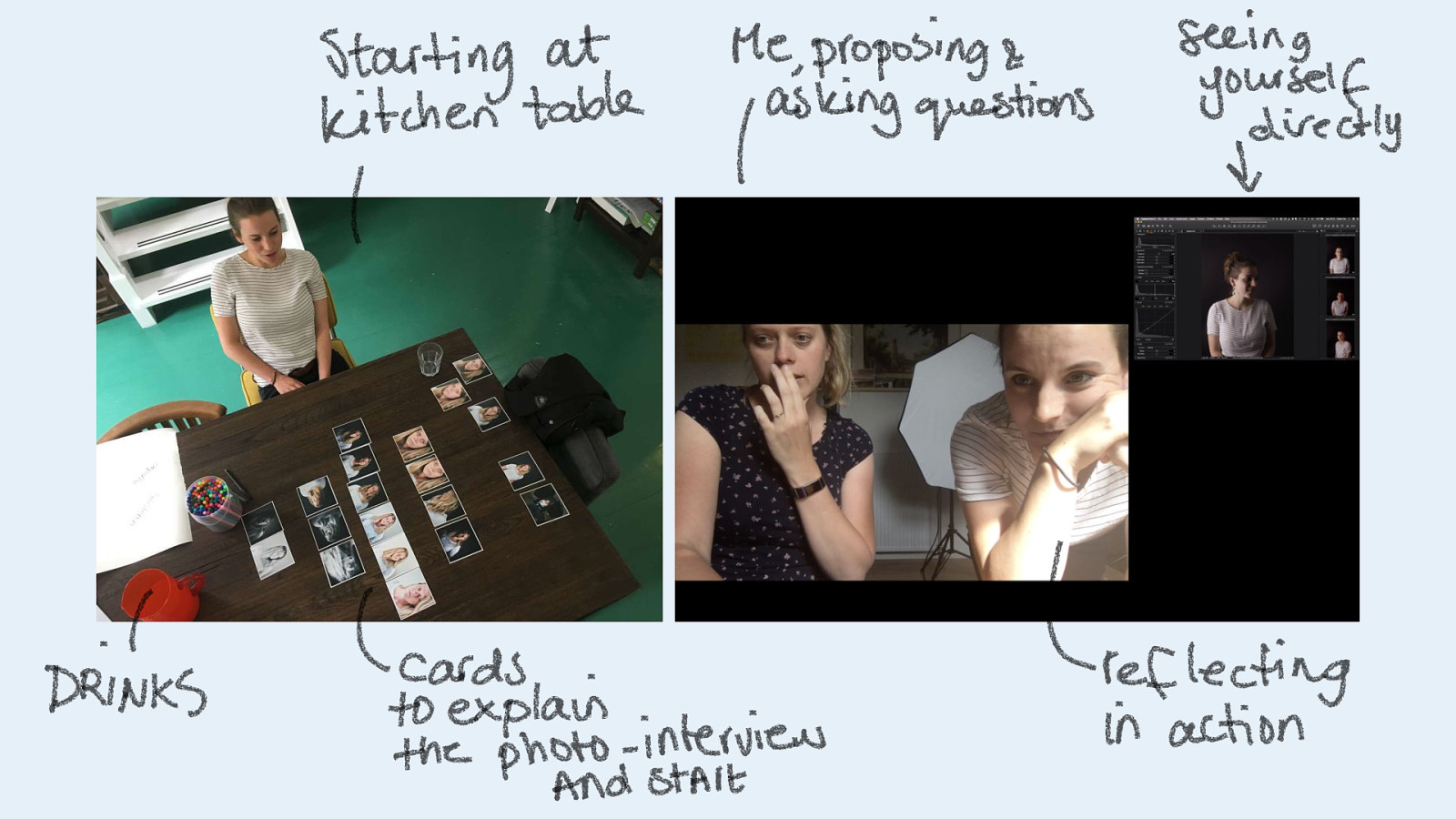

My art based research method is called a photo-interview. It’s a designed experience that has some basic steps.

Every step is thought about in the iteration.

This is what a photo-interview looks like in a time lapse. Even the set-up that we do together has a reason. Because we do this together Roos gets to be a part of the work, so she becomes part-owner of the result. It also eases her, because she gets to do something. The moment that she gets to see herself, her own image the first time - a.k.a. the first confrontation - is also planned. This is my role, my responsibility to know when it’s the right time for this. And to help her adjusting her image by reflecting in the action, during the photo-interview.

You see me asking questions, proposing new lights or a different angle. Trying it out, showing it to her, but ultimately she is the one deciding on the end result.

In this iteration we are researching together how she is as a compassionate civil servant and by doing this we discover challenges that she faces in her work making digital government.

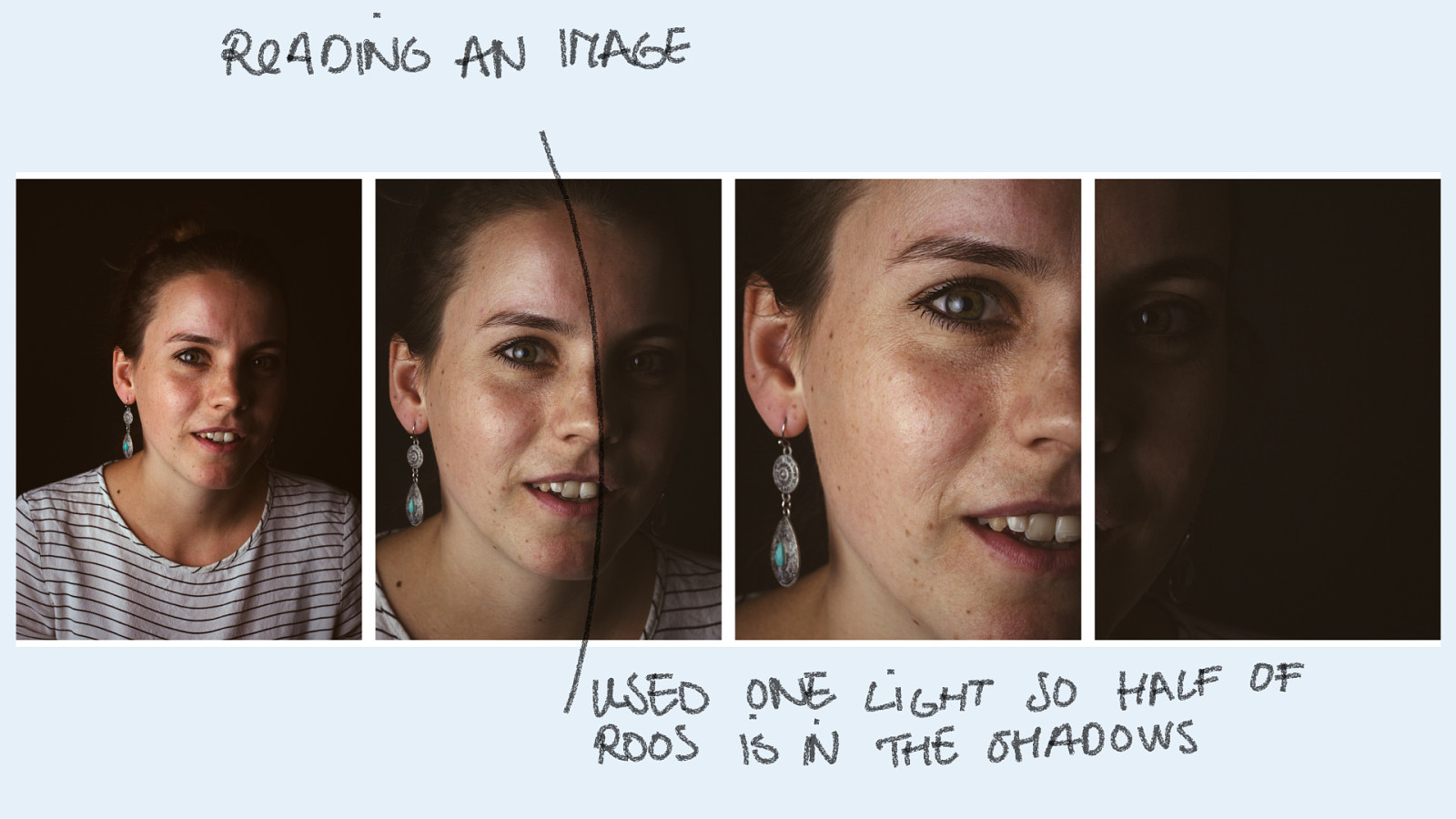

At the end we have a portrait where she shows herself as a compassionate civil servant. If we decompose this image you can almost listen back to the conversation that we had. Roos spoke during her photo-interview about the struggle of working in a highly political environment. That she sometimes would love to see it differently because politics can be the opposite of compassion. You can see this in the way we used lights and shadows on her face.

To read more about the rules of photo-interviewing and the compassionate portraits, read: https://klipklaar.nl/begripvolle-ambtenaren/beeld-als-antwoord/

And then when you have your method, you have to iterate, iterate and iterate some more. You have to do the research to get an answer to your research question.

Every iteration you learn new things. You find new ways and new questions to further research. You really find your way through the forest.

After Elian and Roos I decided on losing the props. In the iteration with Jean (which I showed you in the beginning of this talk) I learned that the simple question works best: how are you as a compassionate civil servant. And after Jean I photo-interviewed 14 more colleagues to collect answers to my research questions.

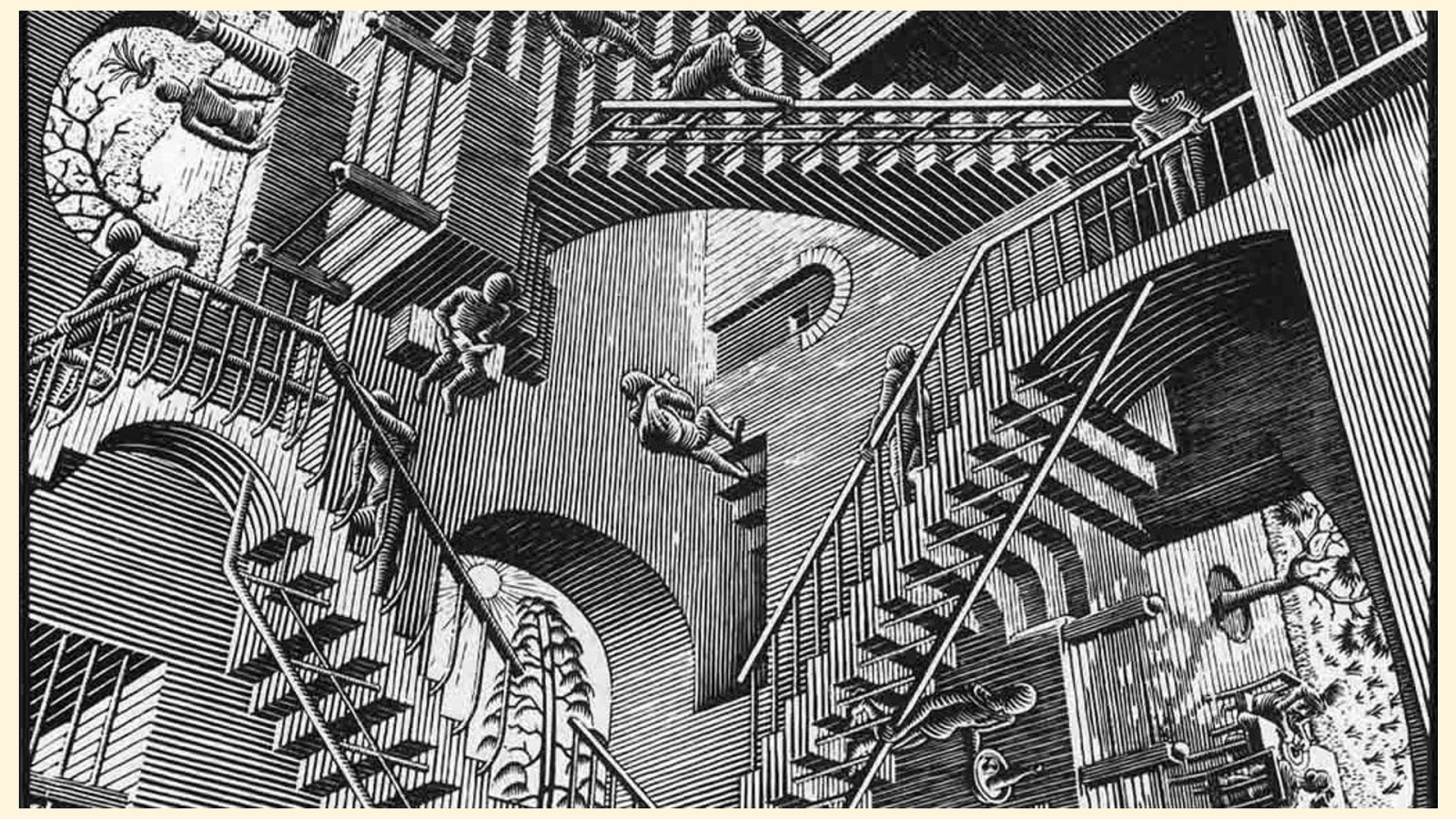

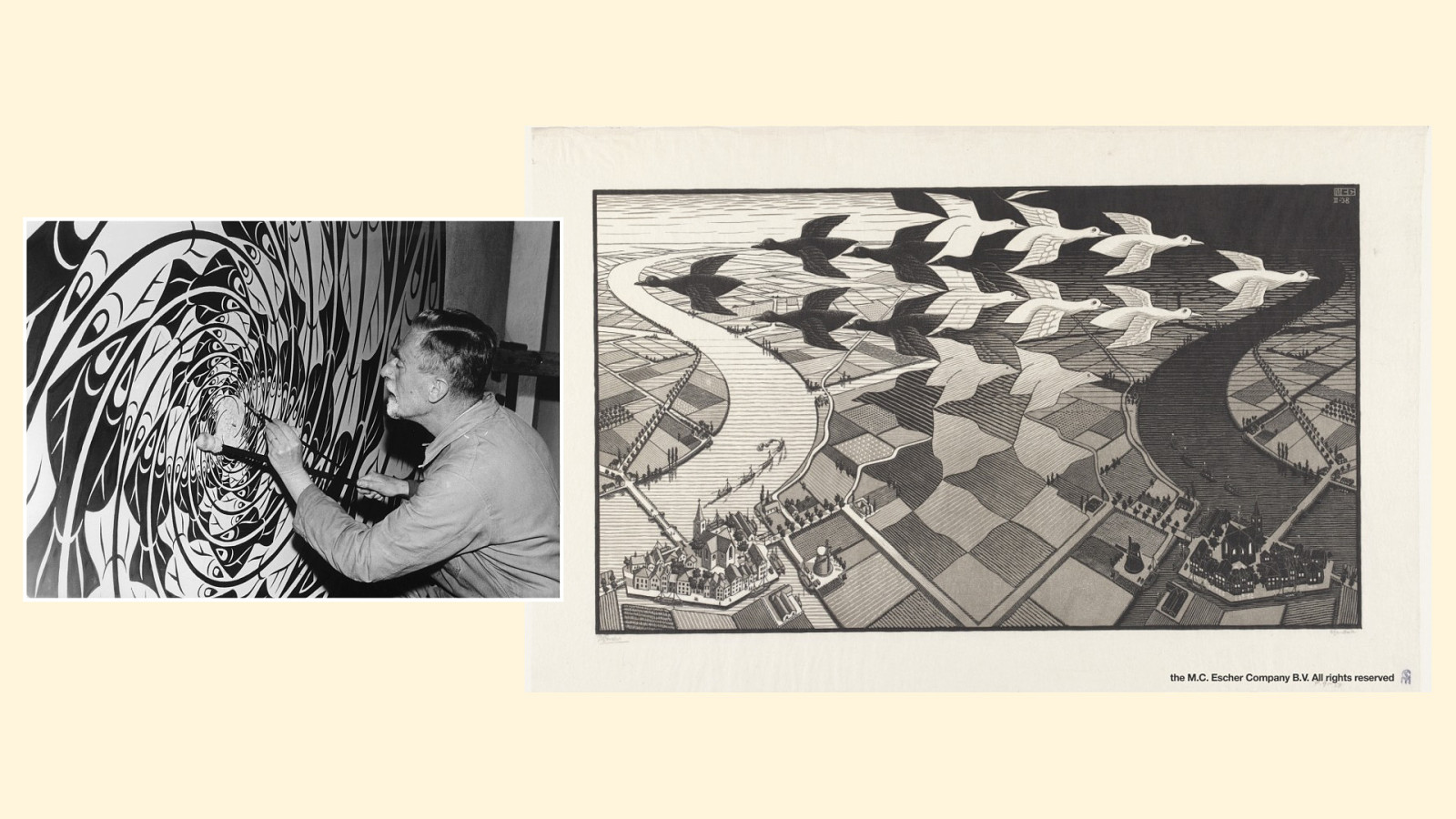

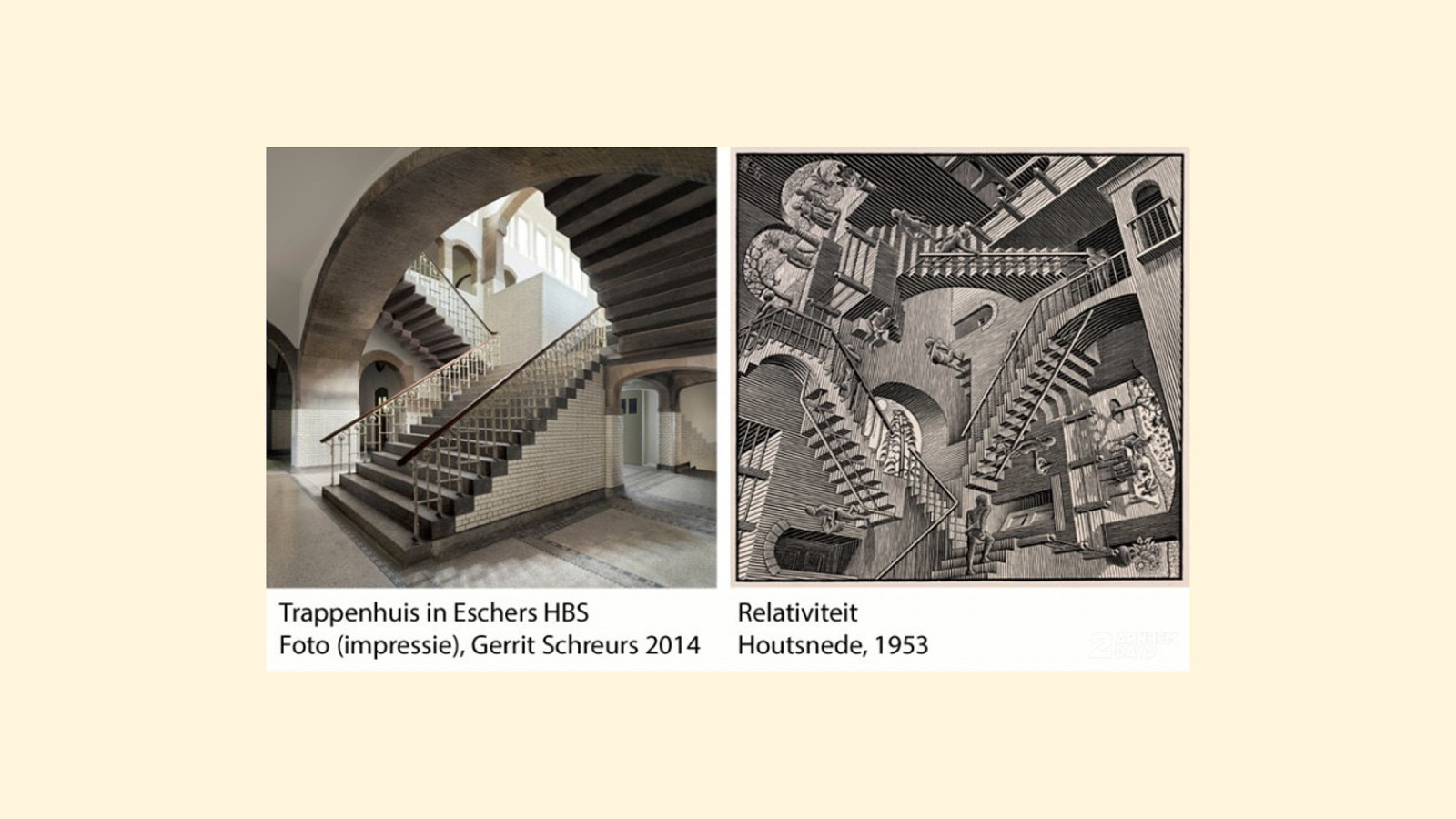

A great example of this never ending iteration process to me is Esscher. He makes these wonderful complex drawings. I’m sure you have seen his works before.

This is him at work. Most of you know Esscher from a couple of his best-known drawings. These birds for example.

For me Escher is a great example for an artistic researcher because he drew to make sense of the world around him. To understand how the world functions. His work is all about math and understanding how math works. He does this by experimenting with the implicit and making it explicit.

But he didn’t woke up one day and made his masterpieces.

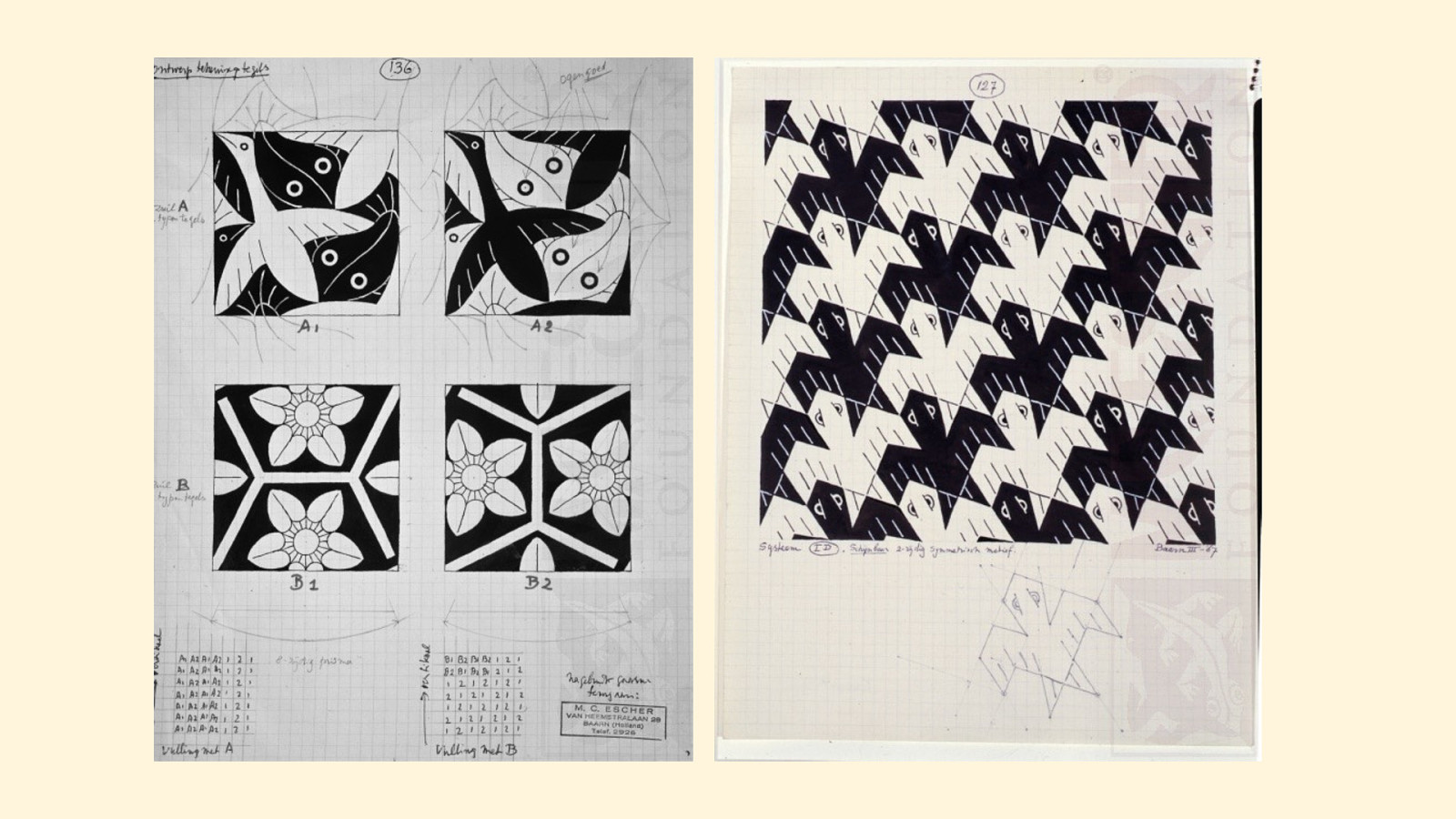

A lot of his earlier work is about trying out different dimensions, trying how things fit and what effect this has on himself and on other people. He works a lot with how one might perceive something. And he iterates, iterates, and iterates some more.

He draws to learn. To study wath these mathematical functions do, how they look and how he can play with them. In the end it has resulted in so many drawings and of course the more complex ones that we all love so much. But it started by just doing, drawing and researching through design. And then iterating a lot and keeping at it.

Your first iteration is all about trying out what happens when you do something.

Let’s bring all the key elements together. Your research question. Your participant and your role. And let’s make a prototype: what are we going to do this first iteration to try out? And what do you think is going to happen? What is your assumption?

Also, don’t forget to document the iteration so you can analyse it.

Last monday I got together with one of my colleagues to watch the first day of UX Insight together. We also talked about this talk. My colleague said about herself what a perfectionist she was and how hard it would be to try doing art-based research. But I think that perfectionism is your friend here, right. Because perfectionism doesn’t happen over night. It happens because you keep at it and try, try again. Because you keep pushing yourself.

So please be perfectionistic about your design research. The impact will be much bigger if you design every iteration well.

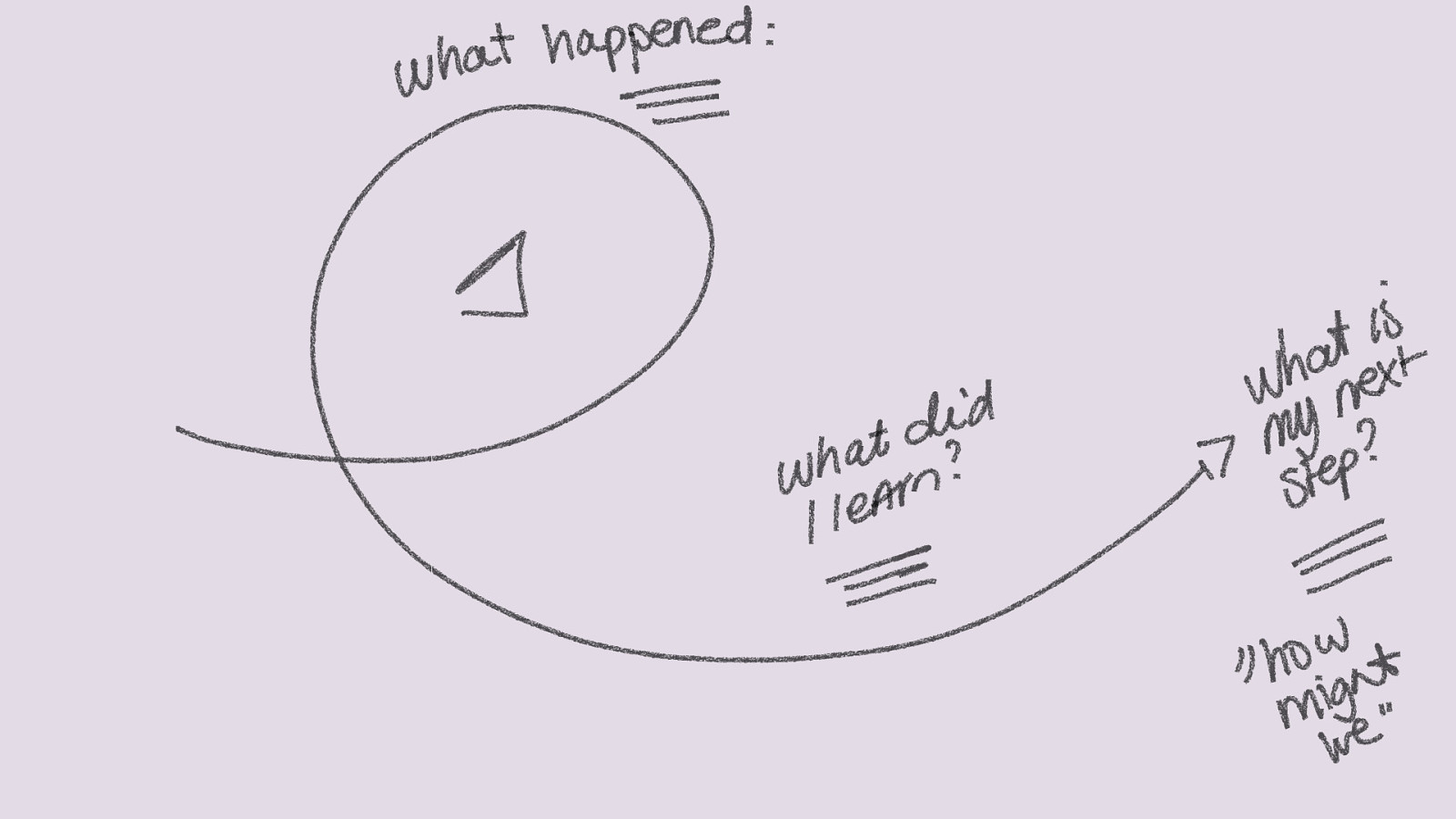

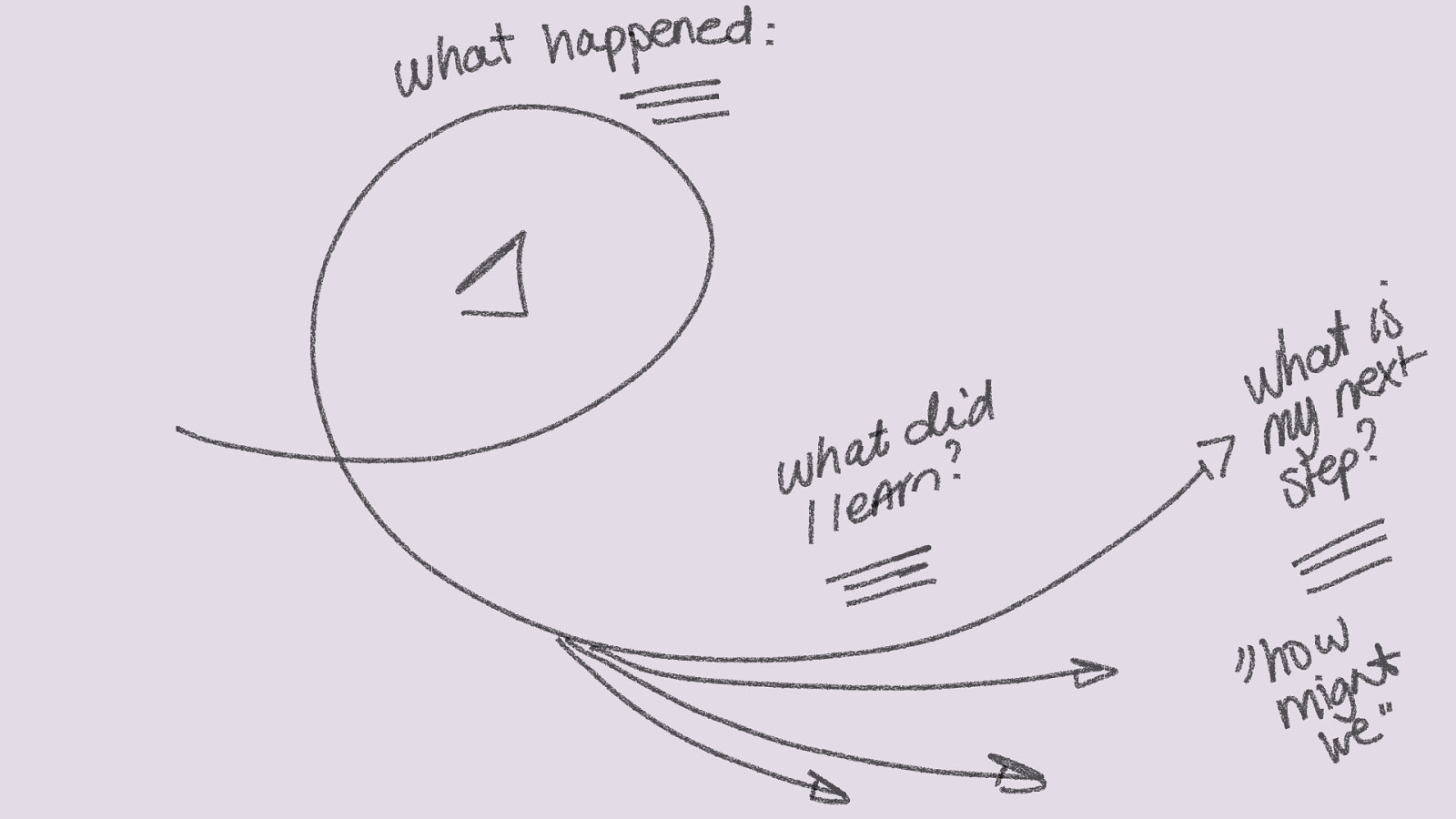

An important step to do this is to reflect between iterations. What have you learned and what does that mean for the next iteration? Do you have an answer to your research question and what does this mean for your overal main objective? Do you need to adjust your method? Do you maybe need to involve other participants as well?

I do this by asking myself these questions. What happened in the iteration? What did I learn and what will my next step be? It helps when you document everything.

I document the iteration by audio taping the conversation, filming the reflection in action and of course with the portraits itself. At the end of the iteration I go through everything. I write down interesting things, notice how the participant looks at themselves, etc.

I combine everything in a blog. Many times I combine this with some desk research to complete the story.

I also write down my next questions. What things do I still not know? This will determine how you find your way and what the course of your design research will be.

You will move up to your main objective. And sometimes the challenges might change, your objective might change because you learned more and you have new insights.

For example… I started with my design research with a yellow rope to connect citizens and civil servants. The more I researched into what it meant to work in government, the more I learned about the challenges that civil servants face. And how necessary it is to reflect about this in digital government. The research method I designed became a powerful way to facilitate this conversation.

More about my research strategy: https://klipklaar.nl/een-veranderende-organisatie/strategie-update/

So you might question me on wether what I do is research or design. I don’t care, actually. It’s both: it’s designed research.

And by doing this we use methods that are more implicit than our traditional methods. They are powerful and help make the implicit explicit.

To begin… just start here. With your first try out.

Design this first experiment by focusing on your question, inviting your participants and to design your research method. Good luck!

And remember: you can never involve your participants too much.

Thank you!