A presentation at Ladies that UX XL in June 2019 in Utrecht, Netherlands by Maike Klip

Hi everyone, welcome to my talk about researching empathy.

My name is Maike Klip. I will publish these slides on noti.st and you can read more about my ongoing research on my blog.

I would like to start by sharing a story with you about a volunteer experience I had when I was fourteen. During the summer of 2003 I spent some time in an orphanage in Russia. I did chores and played with the kids. I had a great time and I thought these kids did too. When I had to leave, one of the girls asked to come home with me. It broke my heart and it had an enormous impact on how I felt. For years I thought back on this experience as the most empathic one I ever had. For me… this was what empathy looked like.

But as I grew up and I started adulting, I read more about orphanages and volunteer projects. I learned that it was a whole industry and that all those young people volunteering on summer jobs led to adhesion problems for these kids. The kids didn’t need empathic but temporary volunteers, they needed the system to be fixed. They needed better care, their carers needed more money and they needed their politicians to make some serieus tough discussions. They needed society to take care of them. And I had been part of this broken system. With my volunteering I even added to the problems that these girls already had. My most empathic experience did not lead to a better world at all.

Sometimes I think back to this experience, especially since I started working in UX. Of course empathy is our holy grail. Isn’t it?

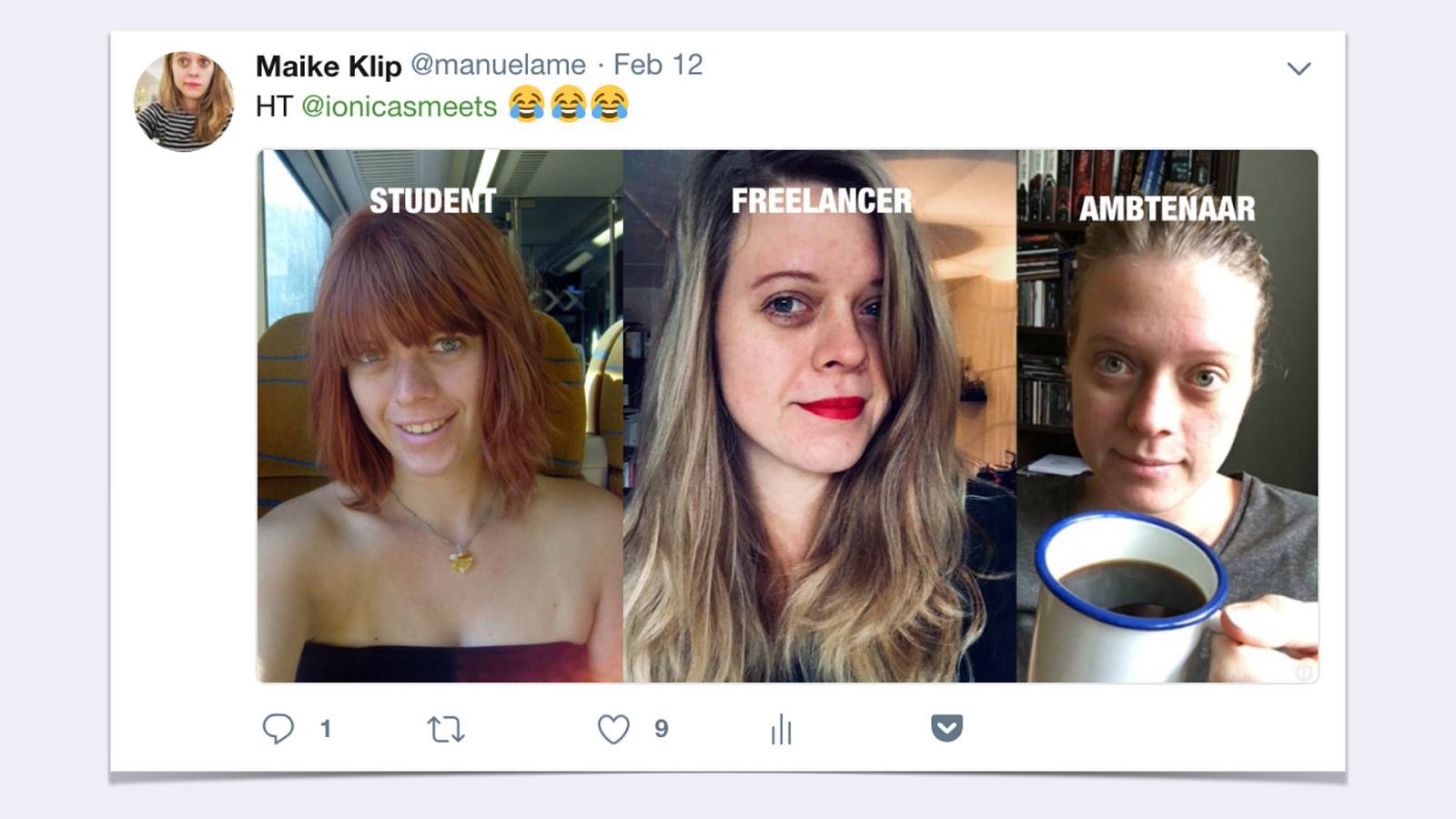

I have worked as a freelancer all my life, but recently I became a civil servant for the Dutch government. As you can see that has been quite an identity change for me. I work as a user researcher at DUO. You might know us best for the student finance in the Netherlands.

I am part of the Online Team of DUO. Our team consists of about 25 people: content designers, interaction desiners, webanalysts, front-enddevelopers en user researchers like me.

This is my view from our headquarters in Groningen.

But I’d rather be here, at a school where I can talk to students, teachers and people working at schools.

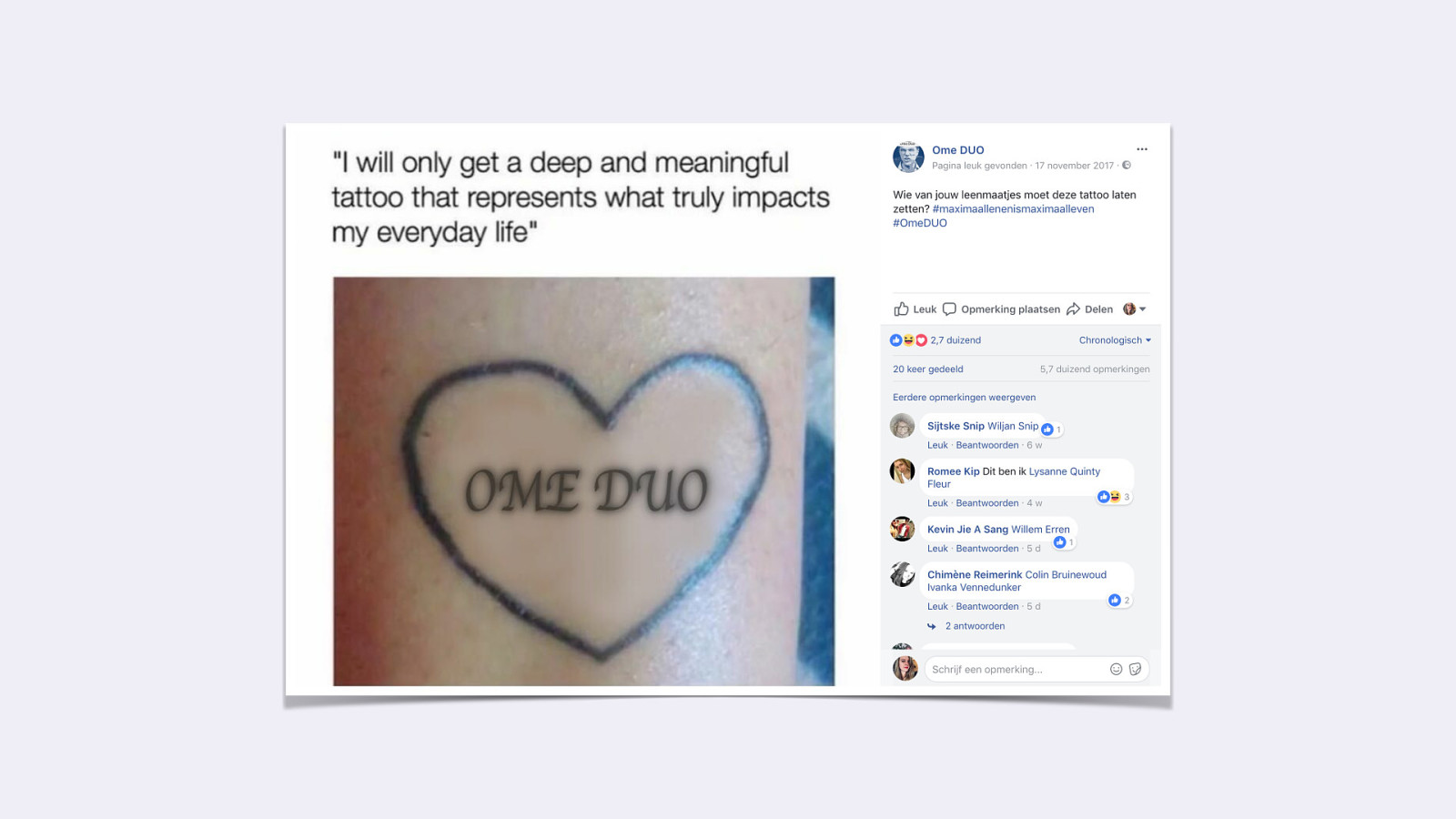

For the Dutch people in the room, you might have heard about ‘Uncle DUO’. It’s a parody account made by students about us. But as a user experience researcher I am looking for this deep and meaningful connection that our users experience with us.

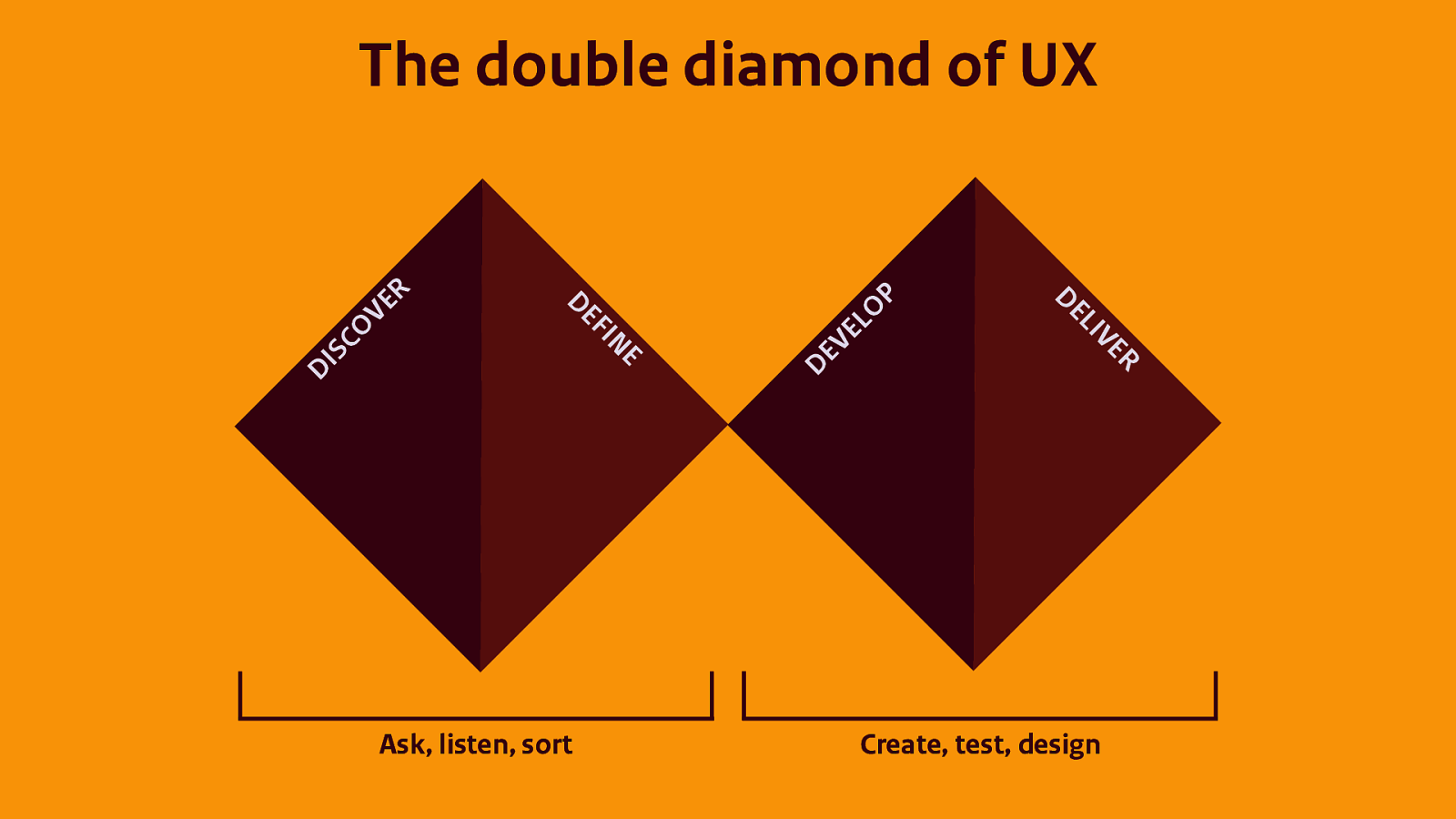

I started working in UX around 5,5 years ago. I have a background in Journalism and filmmaking. Working in UX was very new for me. One of the first things I learned was about human centred design and the double diamond. And how it all starts…

with empathy.

As a filmmaker empathy was a skill I already had developed in my work. To make a story from what other people tell you, you have to have empathy. You have to listen. You have to ask the right question which you can only come up with when you understand.

I used this skill in my ux work the same as I had always used it. By diving head first in stories. By connecting with others and trying to feel what they feel.

Two years ago I gave a talk at UX Insight, also here in Utrecht. I talked about this new ux research method that I liked to call: user friendship. It’s really easy, everybody can do it.

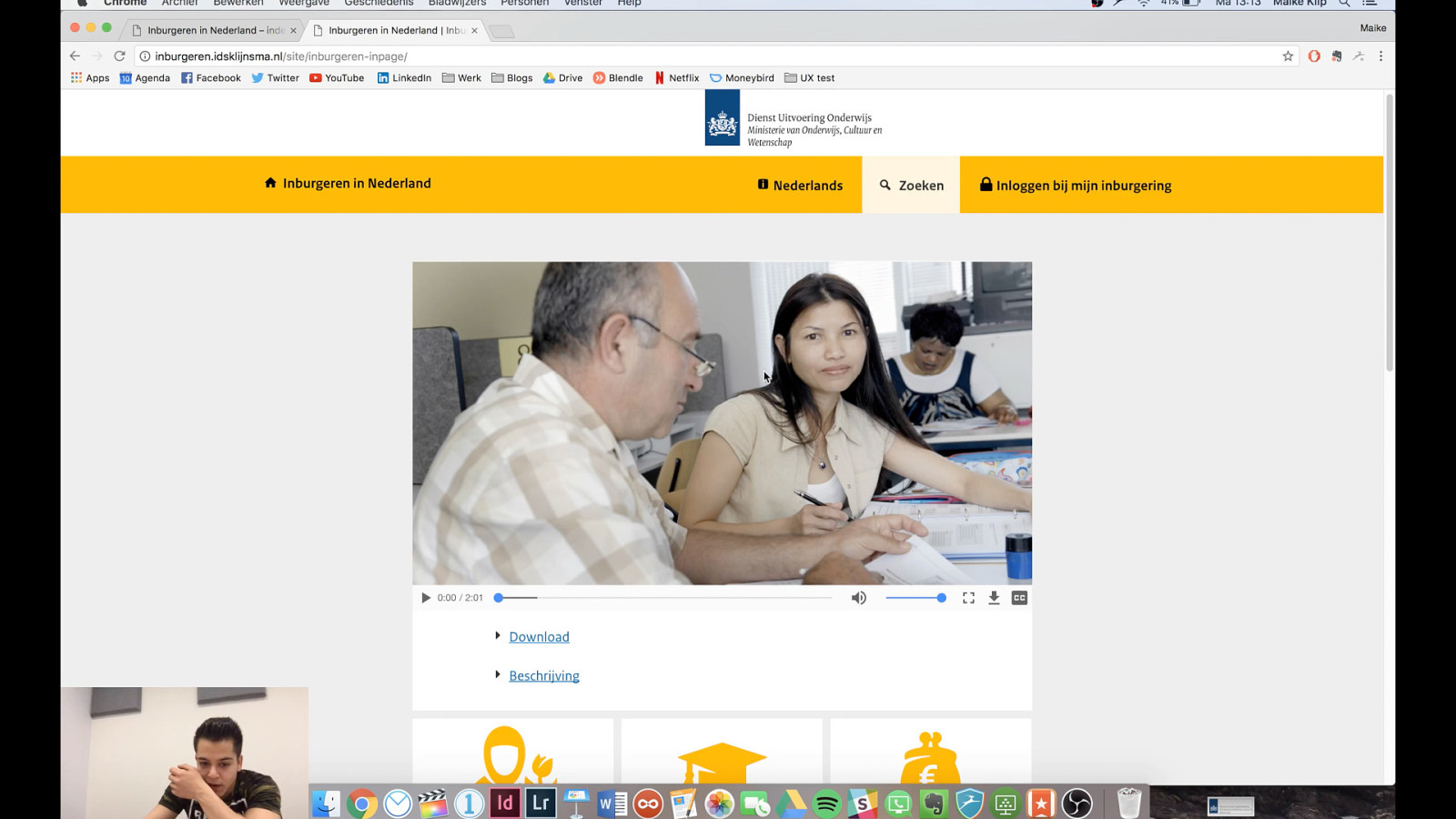

I was assigned on a project at work for the website inburgeren.nl. When you’re new in the Netherlands you have to integrate and learn Dutch. There are 6 exams that you have to take in 3 years to get a permit to stay here. It was my job to research what the main problems with the website were because we were featured on Zondag with Lubach, a dutch tv show that our website was crap.

I started with visiting a few language schools and did some usability testing. But the users that I spoke to where very shy to give me feedback and to be honest about their experiences.

It made sense though. We, at DUO, decide wether or not they pass their exams. They didn’t feel safe to talk freely to me. I needed a new approach.

I signed up for a community in my neighbourhood. I was open and told everyone that I work at DUO, but that I also lived next door. And would like to get to know them to understand better what my work was about.

It was really fun. We had dinners, we spend time at the flee market on Kings Day. We went to Ikea together. We became friends.

But a part of friendship is being yourself. And I am originally not Dutch. I was born and grew up in Suriname. I moved to the Netherlands when I was 14. My first experiences…

…were very cold. Strange. I didn’t fit in and I didn’t belong. I had a hard time adjusting to my new world and I was homesick a lot.

When I started with the community in my neighbourhood and everybody shared stories with me, I started sharing stories too. Of course the reason my parents had to come here, were different than the reasons others had. But the challenge to get to know a new culture, a new set of rules and trying to fit in was very much the same. When I was 14 I tried really hard to act Dutch and to hide my Surinamese side. When I was with my new friends it all came back. My way of talking, my customs, but also the homesickness.

But we shared that as well. And we connected on a deeper level. When you’re part of a group, and you’re good something… it’s only a matter of time that people ask you for your skill. And I was good at governmental stuff and bureaucracy.

The first question I got wasn’t even about DUO.

After that questions came pouring in. And it became so obvious what the problems are between the government and ‘our users’.

For example these are all the organisations that refugees have to deal with in the first year that they arrive in the Netherlands. And at almost all of these organisations you can go to a website, log in, and deal with everything online. Or fill in a form. In Dutch.

But I began to understand that they didn’t know what to do with all these websites because they didn’t knew how the Netherlands worked. They didn’t know how everything related to each other and why they had to do things. Our problems extended the website by far and we needed a different approach on our services. We didn’t had a deep and meaningful connection with them at all, we had no connection.

The conclusion of my talk was that becoming friends with our users was a great way to get to know them and to understand the problems of our digital services. And to really understand them you should get together, have a bite, do things that friends do. And at the heart of that is empathy.

And we did got a new website where some of the problems were fixed. And my talk two years ago ended there. Because what a succes story, right?

But the bad thing about this, is that we just had a new website. We didn’t had a better connection with our users at all. And a lot of the issues that needed to be fixed weren’t because of all kinds of political reasons.

Because my empathy wasn’t everyone else’s empathy. It was different from some of my colleagues who were calling the shots. Different from policymakers and from politicians who decided on policies and execution even as small as what language we had to use on the website (dutch). And that was really hard for me to see. There were even days in this project that I was sitting at home really frustrated, and that my husband Jasper said to me that I had too much empathy. And that was not a good thing.

Is there even such a thing as too much empathy? Yes! It became hard for me to do my job. Because of the user friendship approach I learned insights that I would never have learned with more traditional methods. I still think it’s an amazing approach. But because they became my friends it all became very personal. Maybe I needed a bit more distance. How was I to give objective advise when I was getting personal involved?

My quest to research empathy itself officially started last september when I started at de Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam to do a design master. But when you think about it started earlier, when I did this user friendship project.

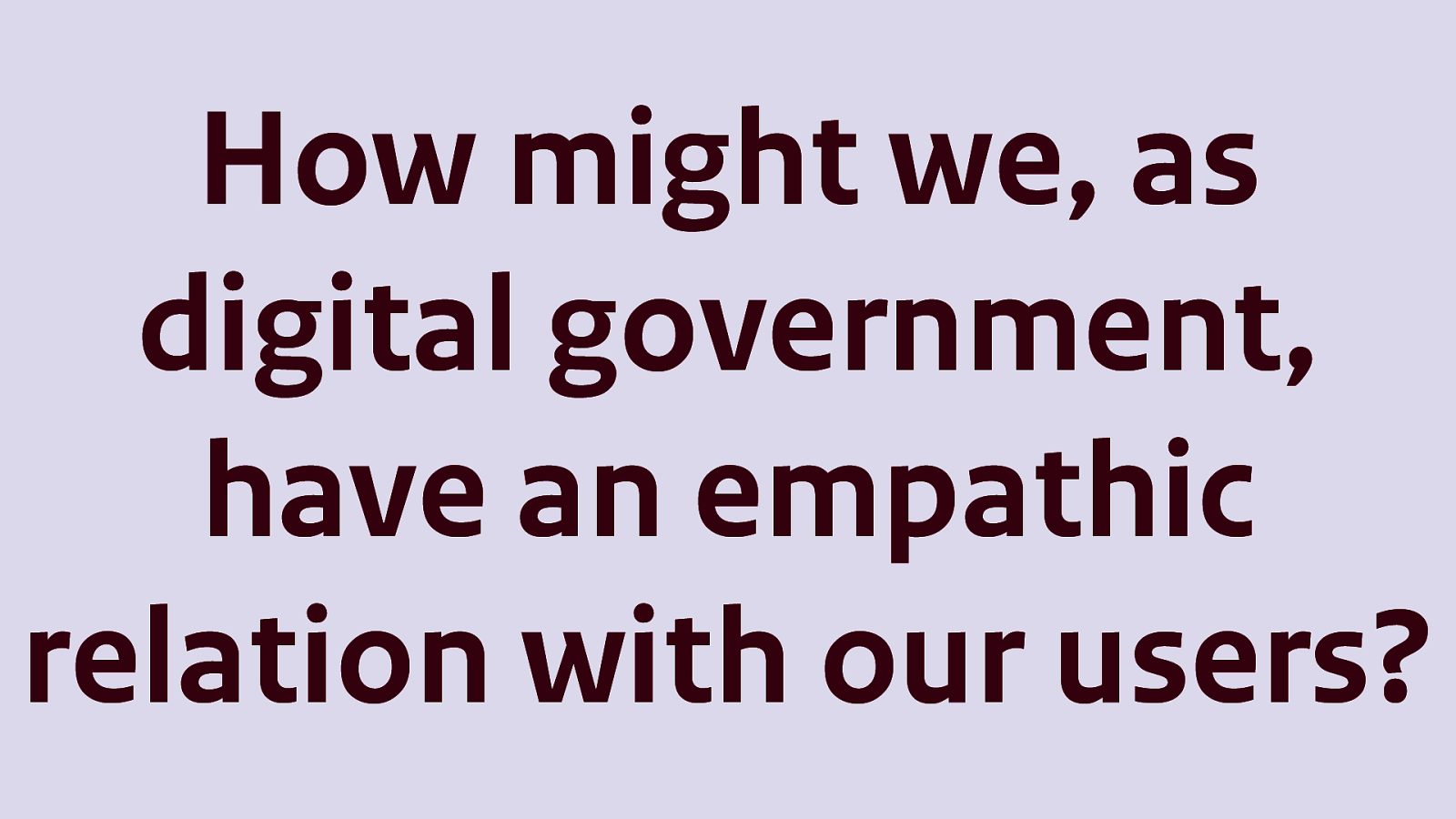

My big question for my research at this master programme was: how might we, as digital government, have an empathic relation with our users?

In the first week I asked people in Rotterdam how they wanted to be connected with me, the government. I had a couple of great, also confronting conversations. Some of them came very close, this man at one point stepped into my personal space, others stayed very far away.

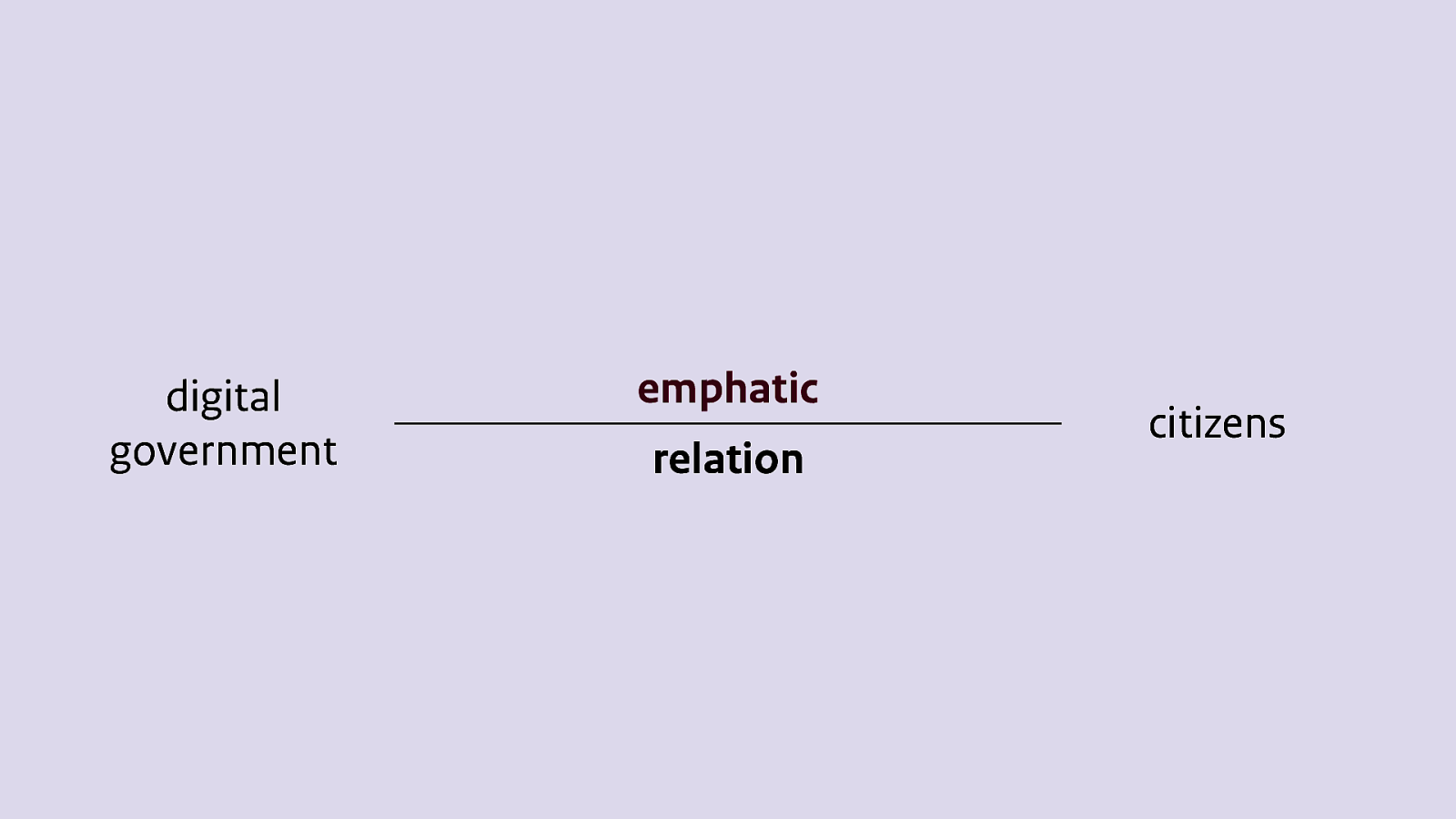

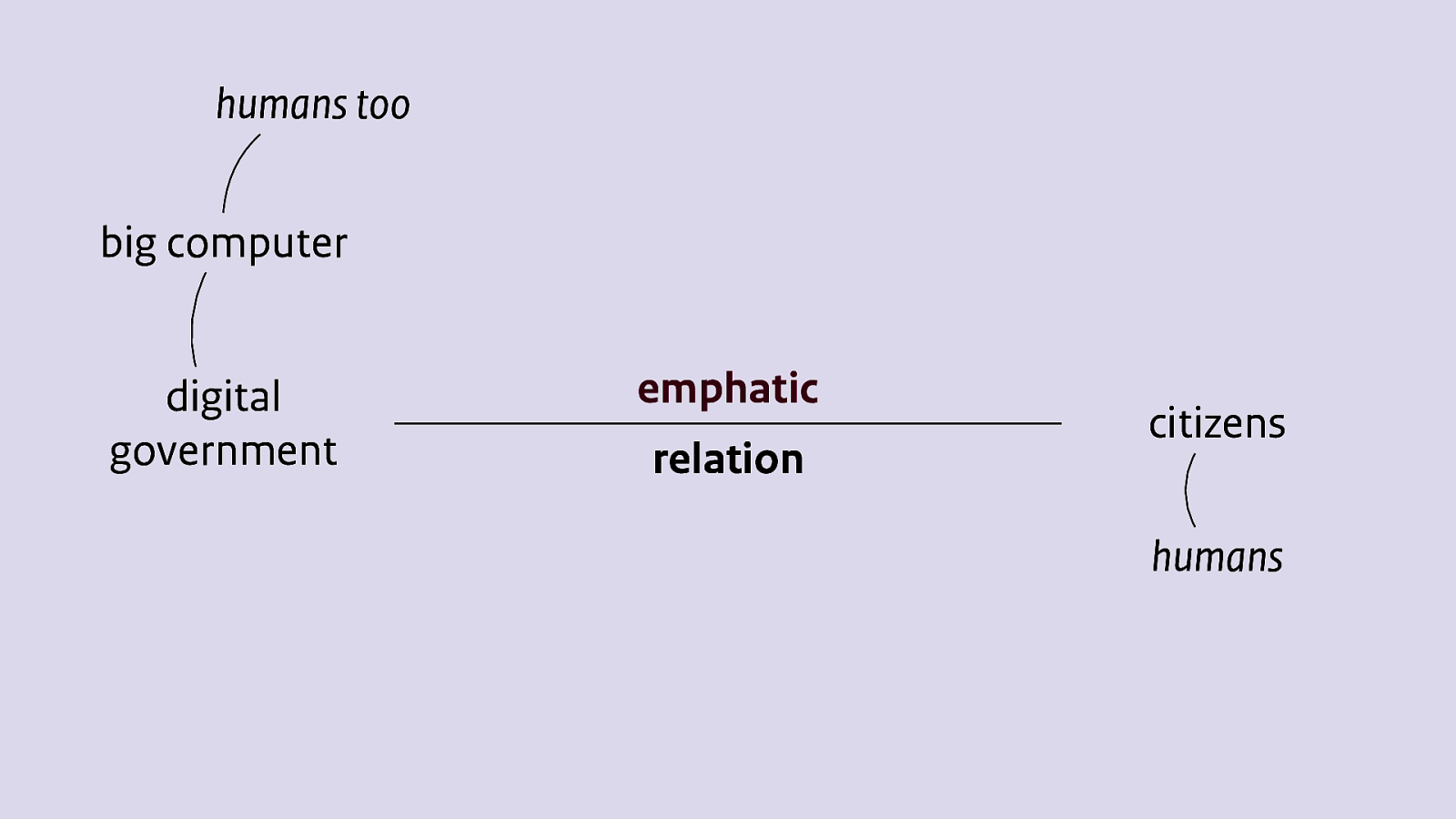

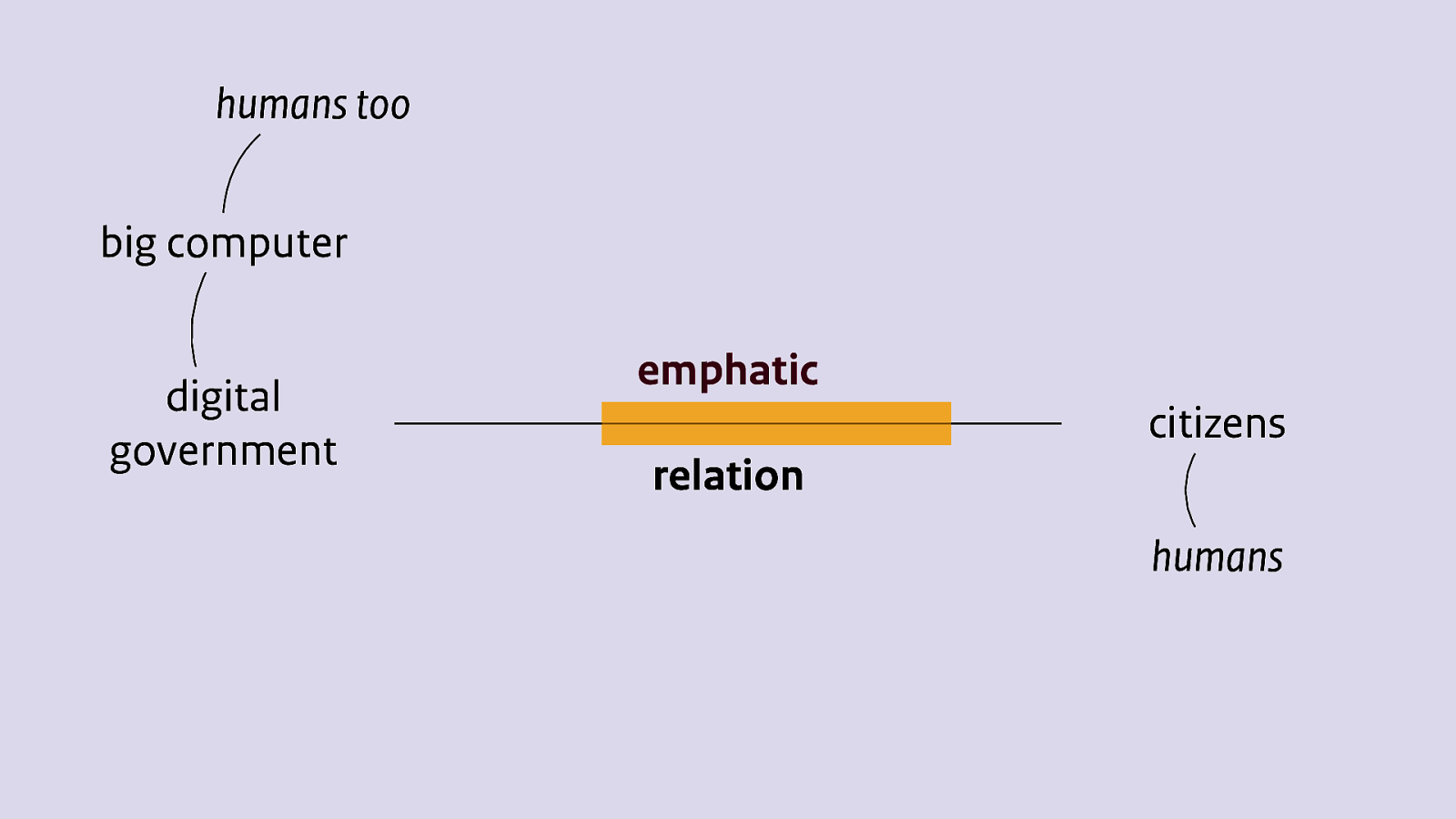

Before I continue, a bit more about this research question. I’d like to put at the center this empathic relation, because I think that’s what’s most important. On the left we have the government, which is becoming digital more and more. And on the right we have the citizens, users, people, you and me.

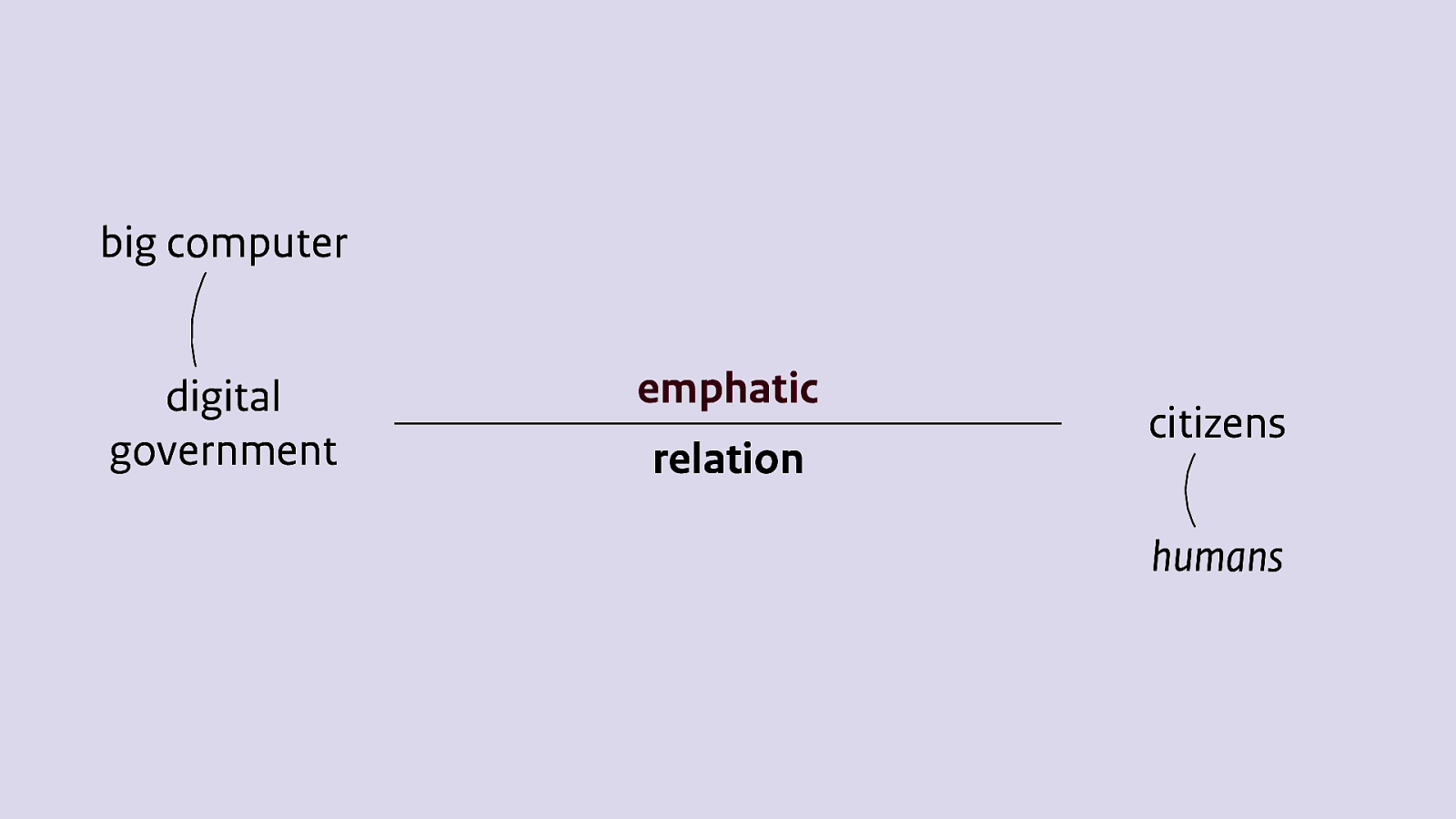

Citizens, they are of course humans. But the digital government, that’s actually a big computer.

But that big computer, and everything that belongs to it: registers, security layers, systems, applications, websites, and much much more… That big computer is made by humans. By civil servants, like me and my colleagues.

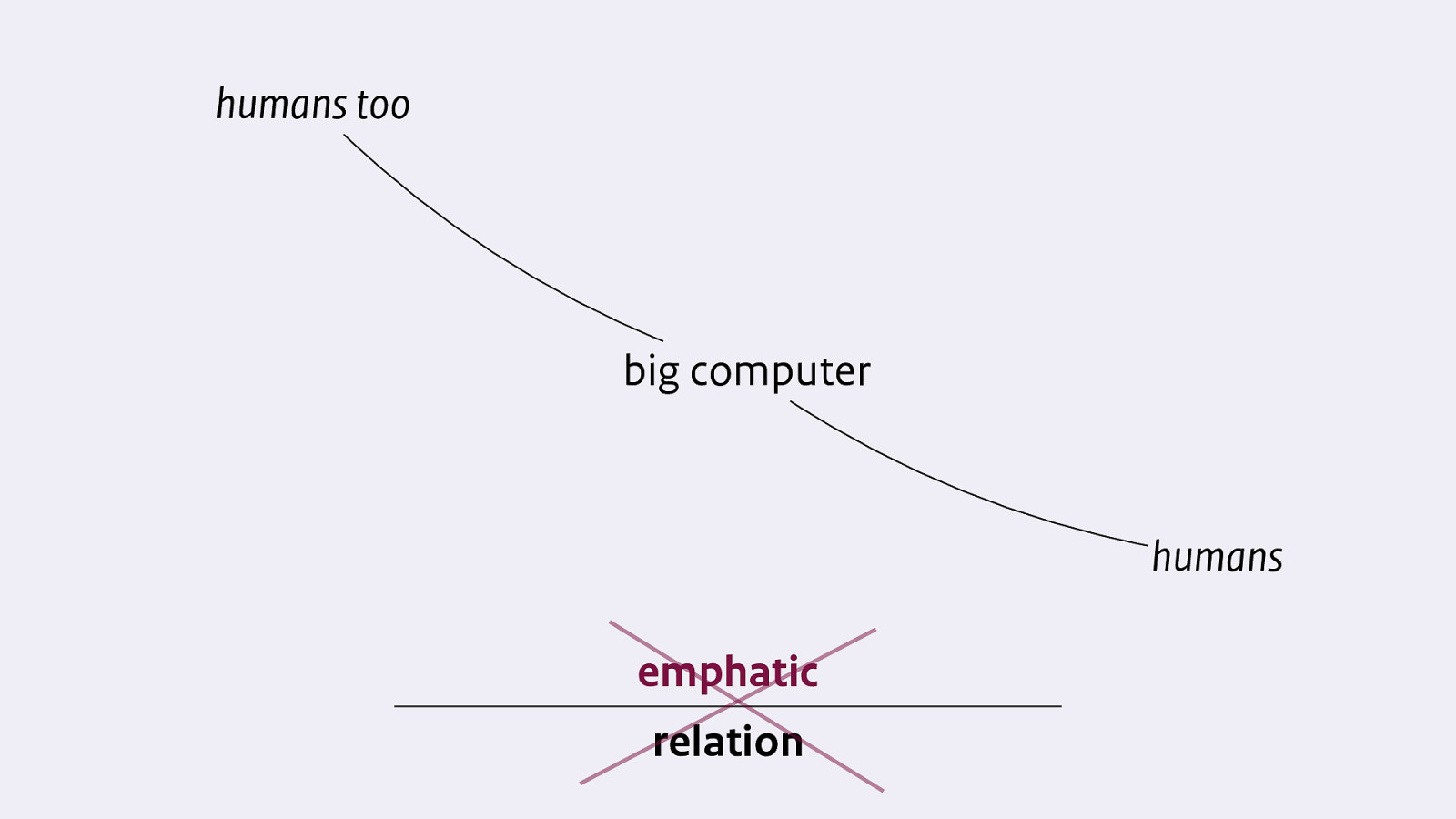

Humans don’t talk to humans anymore. They both talk to the big computer, and in the past 5 years that I have worked in government I noticed that we lost the connection with each other.

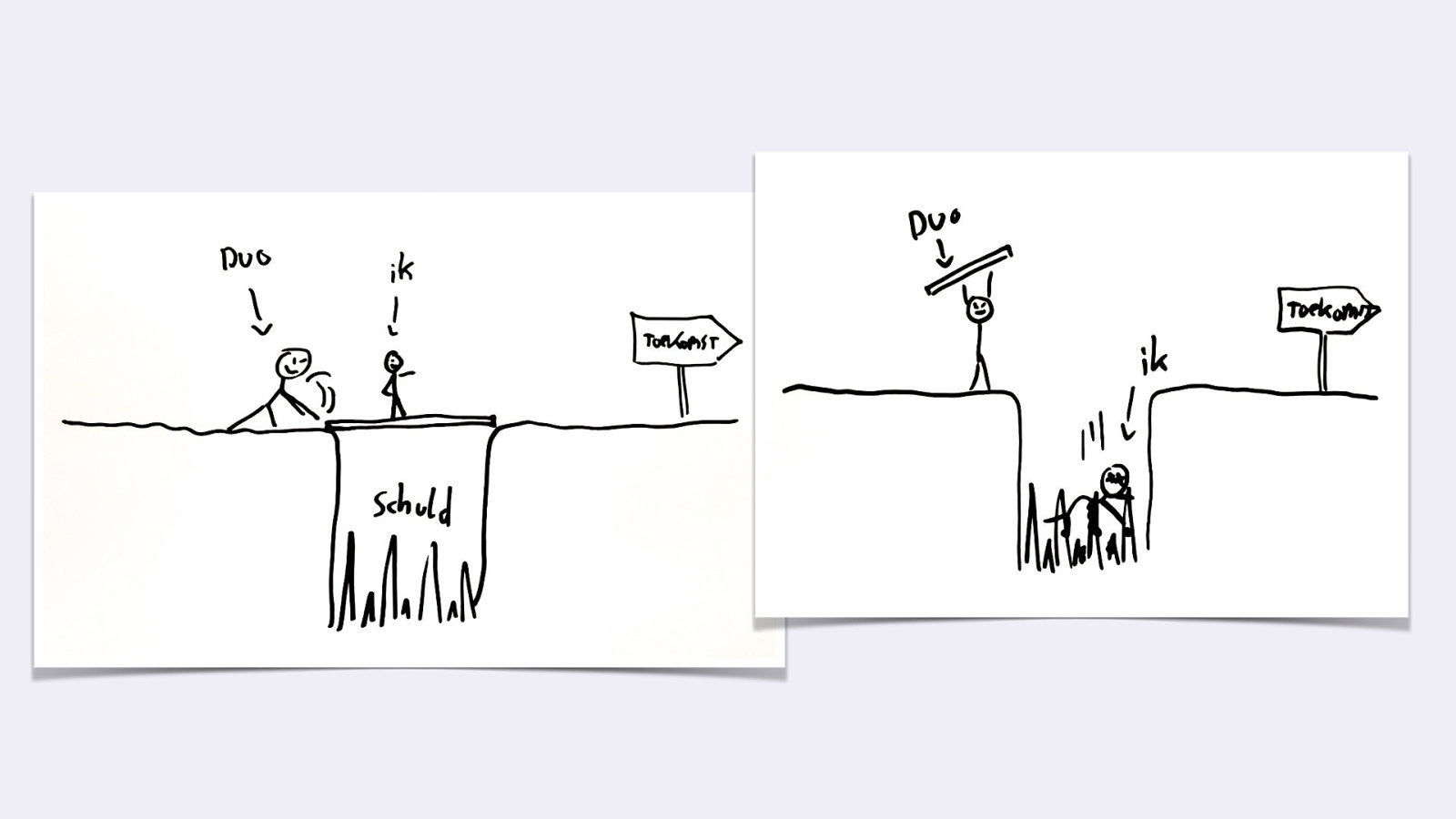

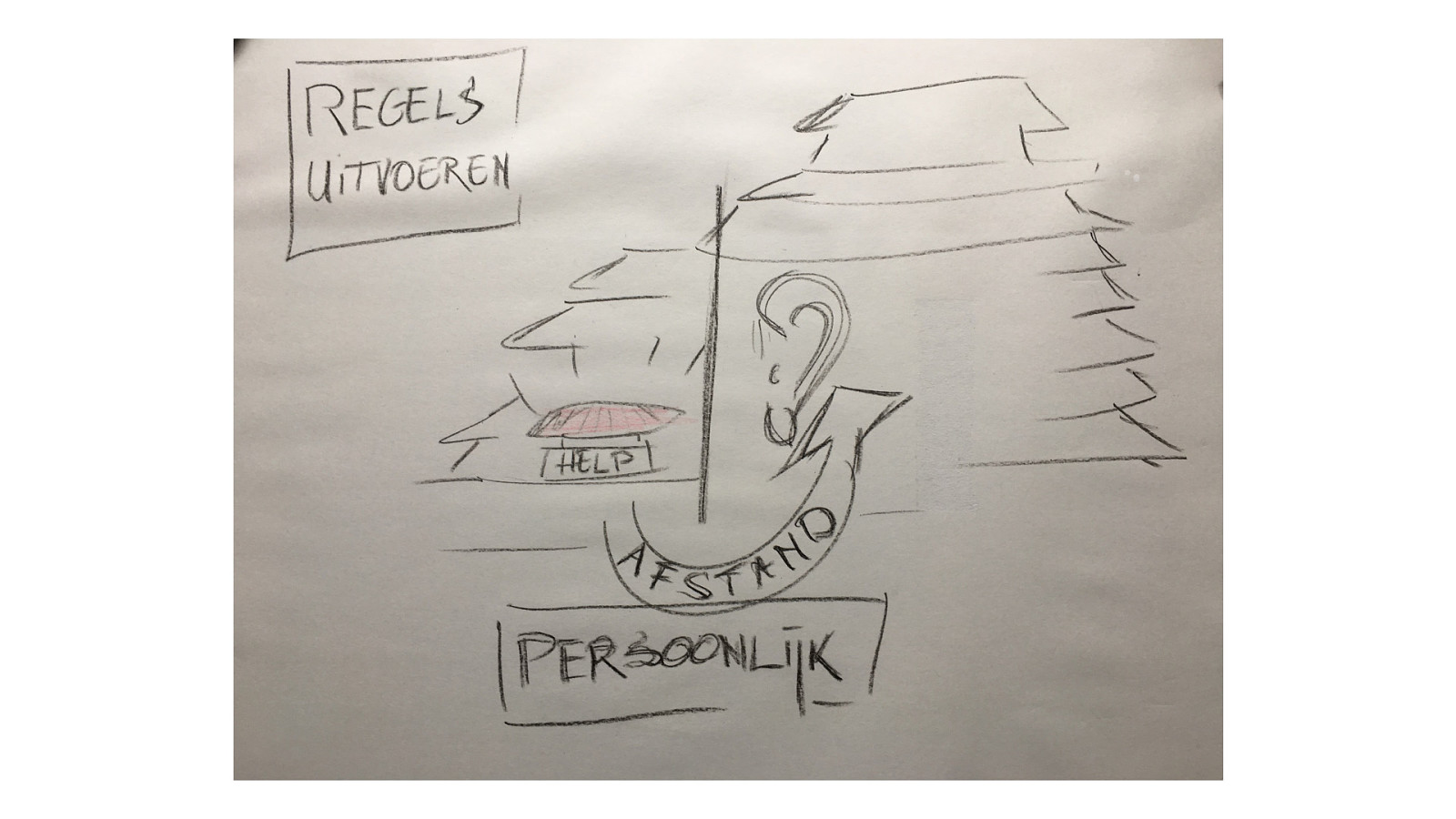

Or, as one of our users drew so perfectly, almost poetic…

It was really uncomfortable for me to experience this bad connection when it’s that obvious that people want to be as far away from you as possible. I wanted to know: can we get the connection back?

My opinion was that empathy was the way to go. That was the key on how to get the connection back. If only everyone felt empathy for our users, the future would be bright. Because empathy is the holy grail right?

I really like this tweet by Caroline Jarrett from 2014. This tweet had a great impact on me because as you might remember I have a background in Journalism. So Caroline, say no more. Stories are the key. Stories about empathy, yaaas! And I did tell a lot of them in our organization. Over the last 5 years…

I organised research safaris with students near our entrance so people can browse through all the raw research data themselves.

I started an in company user research blog to share stories about our users and what they experience.

I introduced a research archive and now we write Sticky Stories for everyone at DUO to get to know our users and learn about them.

I invite students over for coffee, conversations and DUO-tours so they can work with us and colleagues get to meet them in an easy way.

And I bring my colleagues to schools for design days and to hearing first hand from our users what they want and how they experience us.

It’s amazing to see what stories can do to bring back this connection. And to help colleagues to have empathy for the users on the other side of the computer.

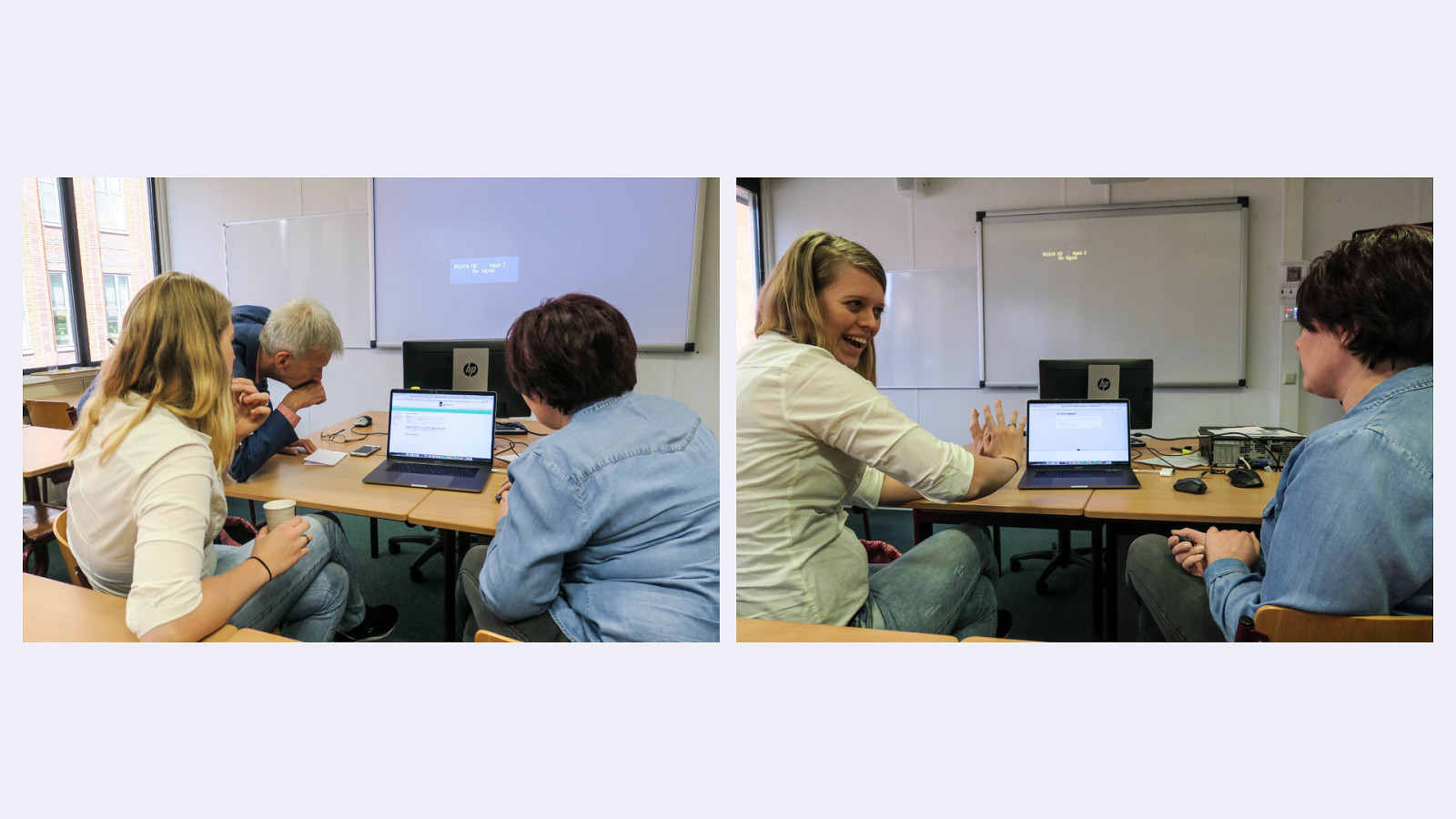

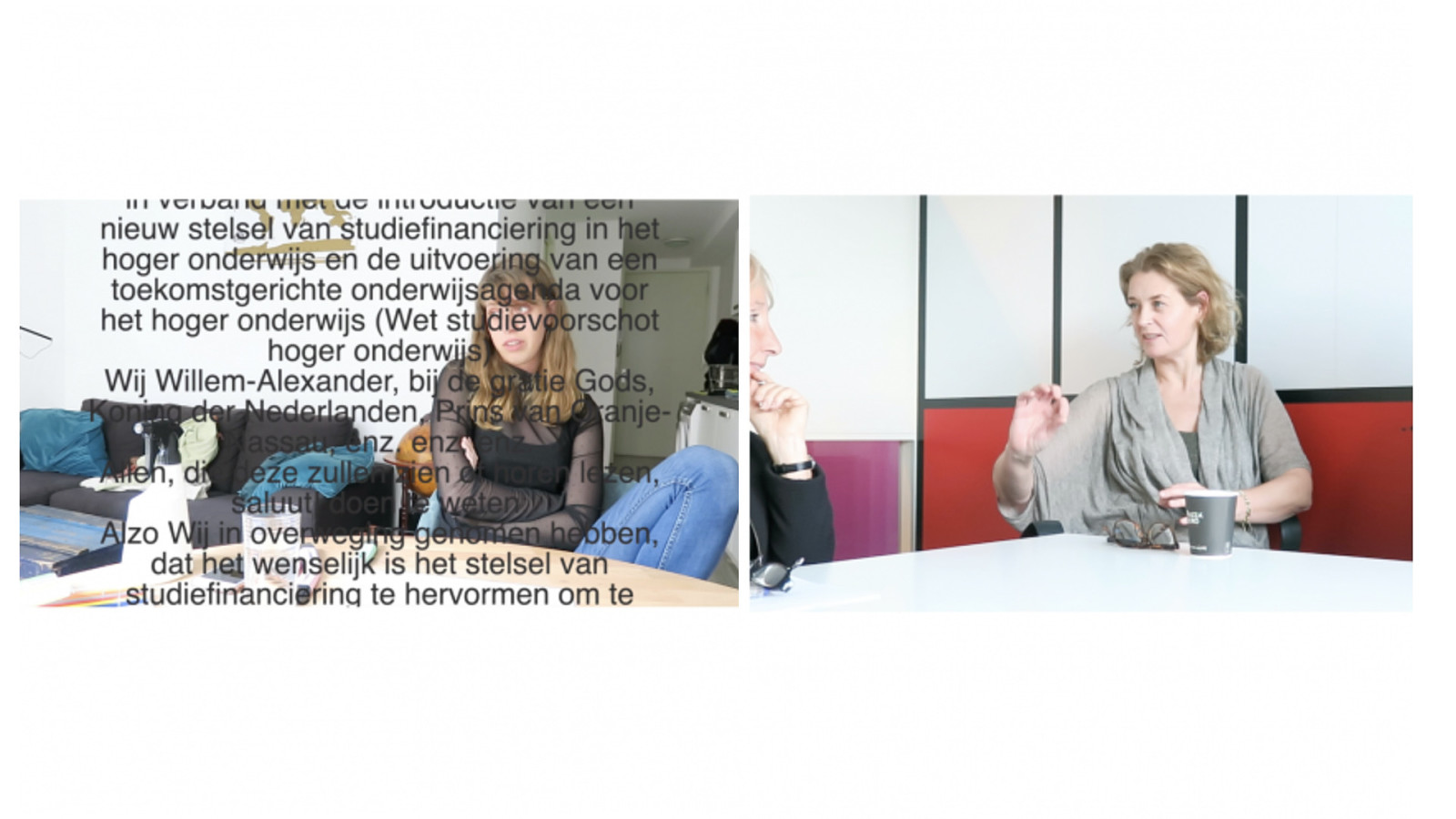

So when I started school one of the experiments I wanted to do, was to see exactly how much empathy you could raise by telling stories. I searched in my story collection and made an appointment with some of my colleagues who wanted to participate.

I showed them a video of an interview with my own sister about her student debt and how she felt about it. Over her interview I projected in text the law of student finance. I filmed my colleagues reaction to the clips I showed them to see if I could capture their empathy. They had to choose to focus on her story or on the law scrolling over her. I wanted to make this paradox clear and actually show the person behind the law. Of course they already knew the text by heart, but they didn’t know the story of my little sister. They found it hard to focus on her story, the text was very distracting, as it can be in real life as well.

I wanted to see what kind of stories and what elements in these stories made colleagues more empathic or not. But something happened that I didn’t expect. They didn’t feel empathy for her. Actually, even the empathy they felt at the beginning of the interview slipped away. One of them said: I raised my own daughters to have different expectations so I find it hard to feel empathy for the choices that she makes. I have a different view on what a good life is.” I wanted to defend my sister but that wasn’t part of the experiment.

No empathy. OMG why not? The outcome was exactly the opposite as I intended.

Instead they had a discussion about how hard it was do your job and be empathic when that’s not in your job description. Working in government you first have to execute the law. “Our employer never says anything about empathy. The law doesn’t either. We just follow our gut. But sometimes we can’t even do that.” They also said that I told the wrong story. And that if I had told another one, which with they could have better related, they might have felt more empathy. For example why wasn’t I telling the stories of single moms in debts who couldn’t pay their school tuition instead of the one of my ‘spoiled sister who cried over her student debt’?

Empathy has some flaws. We tend to have more empathy for the people we know and like. For those who ‘fit us’. Like me and my sister. There’s little that she can do that would make me stop caring for her and I would never call her spoiled. But a single mom in debt… I don’t know any single moms in debt. And I realised that I never spoke with them in my research assignments. How could I have been so blind?!

We often find it hard to have empathy for people who are different than us. It’s harder to connect, it’s harder to care. Empathy is a feeling and not rational at all. But I don’t believe in telling a different story because I we should have empathy for all the stories. Me for the single mom, but others for my sister. But that’s just nog how empathy works I guess.

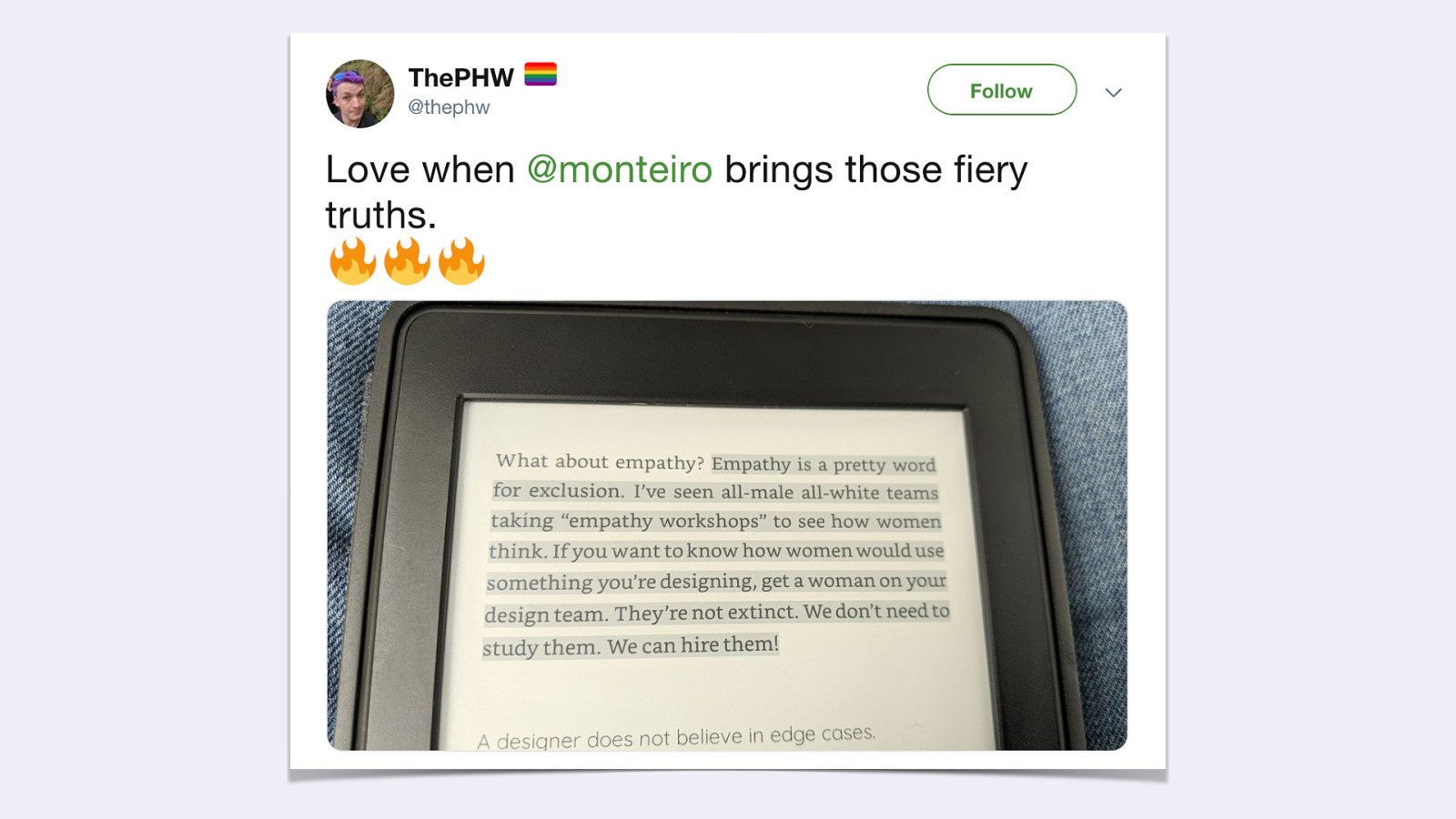

As Mike Monteiro says: Empathy is a pretty word for exclusion.

I started reading books I would have never chosen by the title alone. Too much empathy? Against Empathy? I mean are you kidding? Empathy was our holy grail right? How can you have too much of it, or be even against it? Do we need less empathy?

These writers go so far as to say that we should organise the care for each other so that we don’t have to feel empathy anymore. For example an orphan child shouldn’t need random volunteers to take care of her, as society we should organise that orphan children have the best care in the world. The government should take care of that, right? Then it’s not random anymore, everybody can have acces to the same. No empathy needed because we fixed the system.

And as government we can take this even further. We can build a system, a big computer that makes honest and good decisions, based on algorithms that stem from just and rightful policies. We really don’t need empathy anymore when we have a great system. Right…?

But policies are thought of by humans and this big computer does not make itself.

About a year ago I had a conversation with one of my colleagues who works as a strategic policy maker. I asked him to brainstorm with me about my research question. And he lingered a moment when I said the phrase ‘begripvolle verbinding’; empathic relation. He asked: “Empathy… Interesting… How much does empathy cost?”

He looked at me and I never heard that question before. How much does empathy cost? Like… in money? “Yes,” he said, “And could we also have like 7 empathy instead of 10, and then it would be a bit cheaper but still good enough?”

“Because we don’t only have a responsibility to students,” he said. “Also to society. We are paid by tax money, student finance is tax money, and we should be able to make a calculated and rational decision about our services to both the individual and the collective.”

I discussed this later with a friend of mine while having a beer. And I heard myself saying that we should stop with the empathy part in design. At all. He looked at me and said “No. No, we shouldn’t.” He took it even further and that night we came up with the term: empathy debt. Not money, but emotional debt to our users.

The makers of the digital government, we the designers of this big computer, we are the translators of empathy. We are the ones who are building the system. So the responsibility to make it good is on us. And it’s a big one. And the more we wait, the bigger this empathy debt becomes.

If we, as civil servants, don’t have empathy… how is the relation that citizens have with government going to be a good and empathic one? And the more we wait, the more debt we are building as government.

We have to start talking about the way we are connected. About our empathy.

So that meant I was back at my original question. I had already seen that we lost our connection and I didn’t knew exactly anymore what empathy meant at that point point. I felt like a doggo in space.

I went back to the beginning. What would happen if we just got back to that connection. What would happen if this yellow line was actually real and just for a moment we could walk past the big computer and meet each other. What would my colleagues say? What would they do? And how would they feel or want to feel empathy?

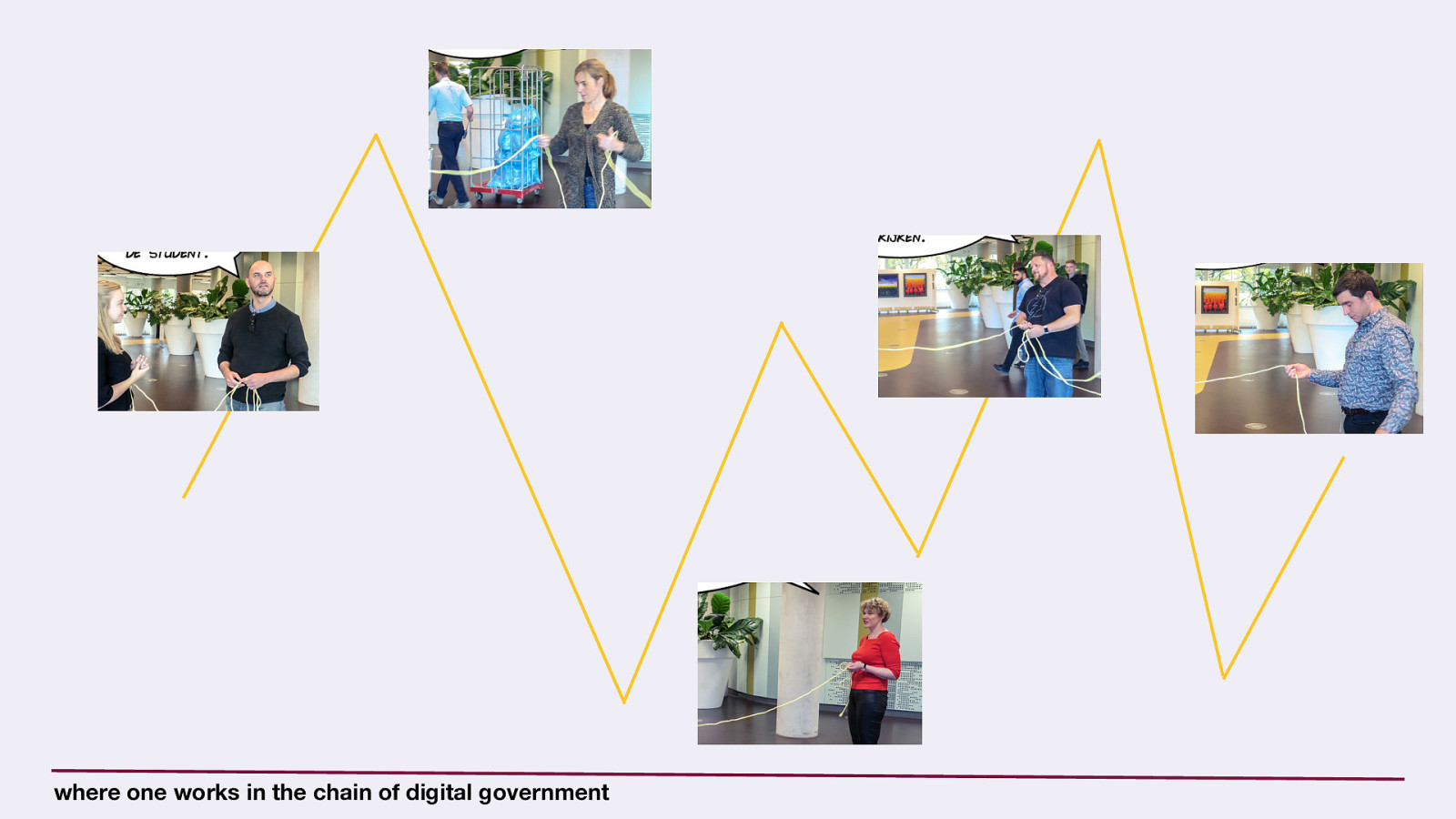

I asked two students, Milo and Britt to help me set it up. Britt tied the robe around her waist, just like I did on the streets in Rotterdam. She asked: I’m a student. How close do you want to be connected with me? Because of the robe and the actual stand colleagues had to take, it was a very intuitive experiment. They had to ‘feel’ how they wanted to be connected.

I asked colleagues who worked on the big computer. For example my colleague Grat. He is the product owner of the service team Test Automisation that helps other development teams build ‘the big computer’ that is the digital government which has the relation with a citizen. He is almost five lines away from the user.

How does he feel connected with students?

With every colleague I spoke I had a different conversation. Some were standing really close, others far away. Some thought it was very confronting, others had fun.

Everyone had a different view on how this relationship should be. On what role empathy should play. And what role we, as DUO, should have in this connection. When I looked at where my colleagues worked in the chain of the digital government, I noticed no pattern at all. Everybody had their own view. I felt clueless again.

Empathy is a very personal feeling. And every person is different. So everybody feels it in a different way. Sometimes it even depends on what role you have.

As my colleague Marianne says: I want to come closer, but I don’t think that’s professional.

So by now we stated that yes, we have to have empathy. BUT… we shouldn’t be too close. But we also shouldn’t be too far away. And we really have to consider that empathy has some big flaws. And that it is a very personal feeling. I always thought of empathy as a yes or no thing. Either you are, or you’re not. But as this experiment with my colleagues showed me… everybody took a different stand on the yellow robe.

Could empathy be a scale instead and be much more nuanced than I ever thought?

And if empathy is a scale… how much empathy do we actually need? And will there be room in this scale for every one of us, just the way we are? And what kind of empathy would that be so we could channel it in the ‘big computer’ that we’re making?

Beside my job at DUO, I am also a photographer. I love shooting landscapes, but also love making portraits.

I speak photography. I see the world in images. That is a language that is really close to my heart. It doesn’t only speak to your rational mind, but also communicaties to a much deeper level. You can feel photography. In photography I work with scales all the time. So I tried to speak my own language to better understand empathy as a scale. I’d like to teach you some of the basics.

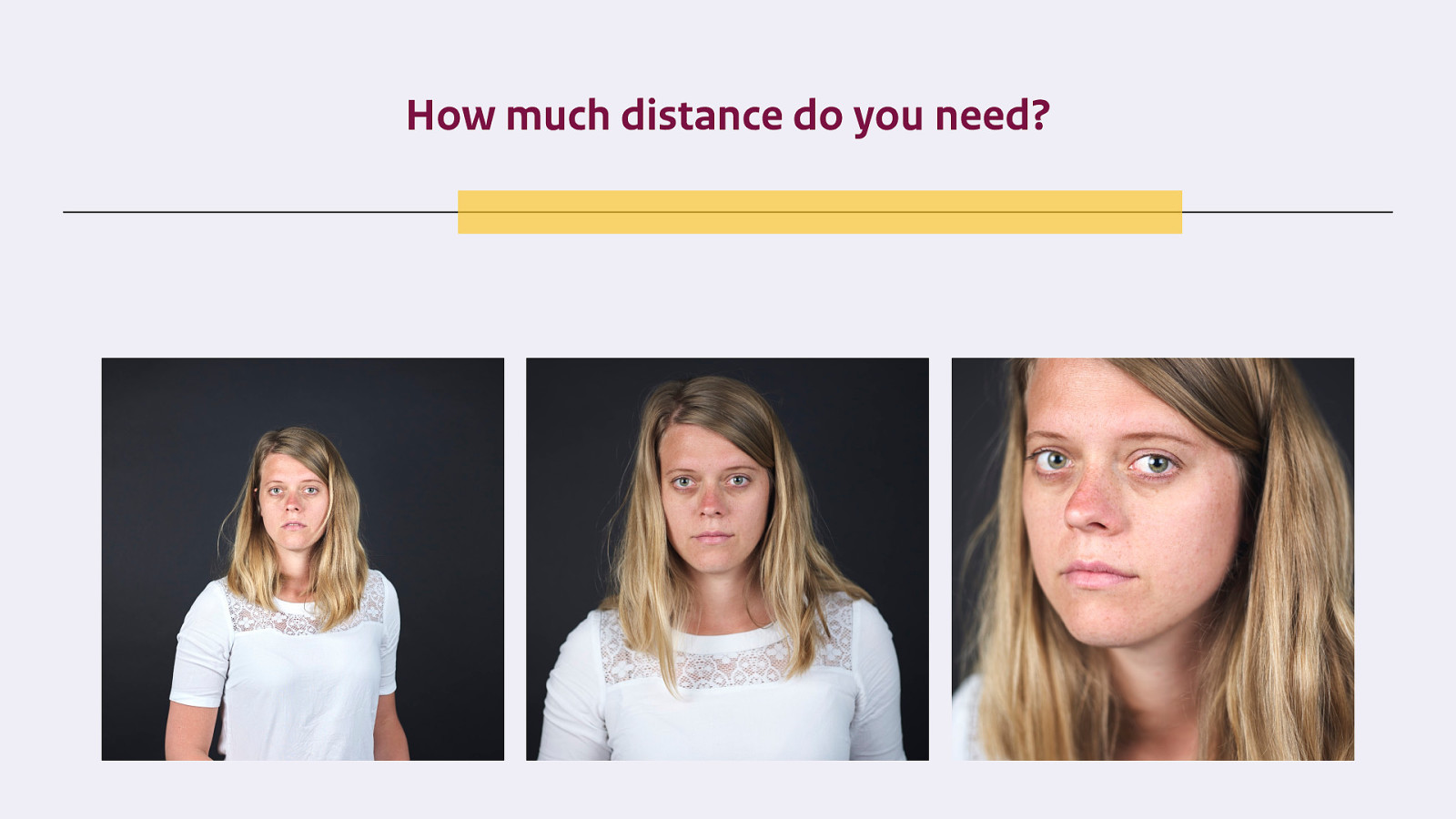

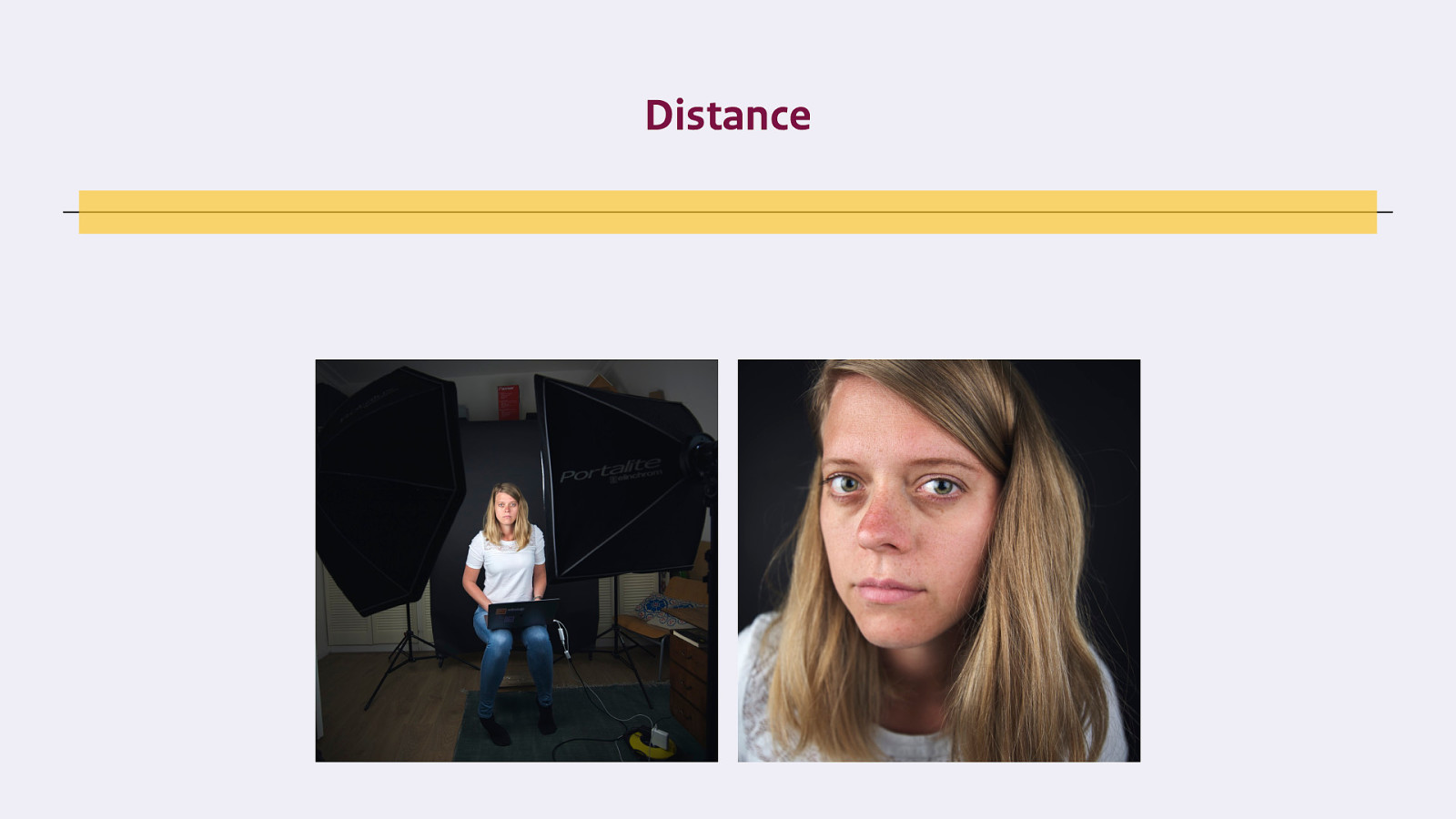

For example. When shooting a portrait of someone, one of the first things I consider is distance. How close am I going to be to the one I’m portraying. That way I can choose what lens to use. Here I used a portrait lens of 80mm and for the close-ups I took a step forward.

With a wide angle, a 28mm, you can see everything, even the behind the scenes stuff. When I come really close with a wide angle, I get so close that everything gets distorted. Maybe this is too much?

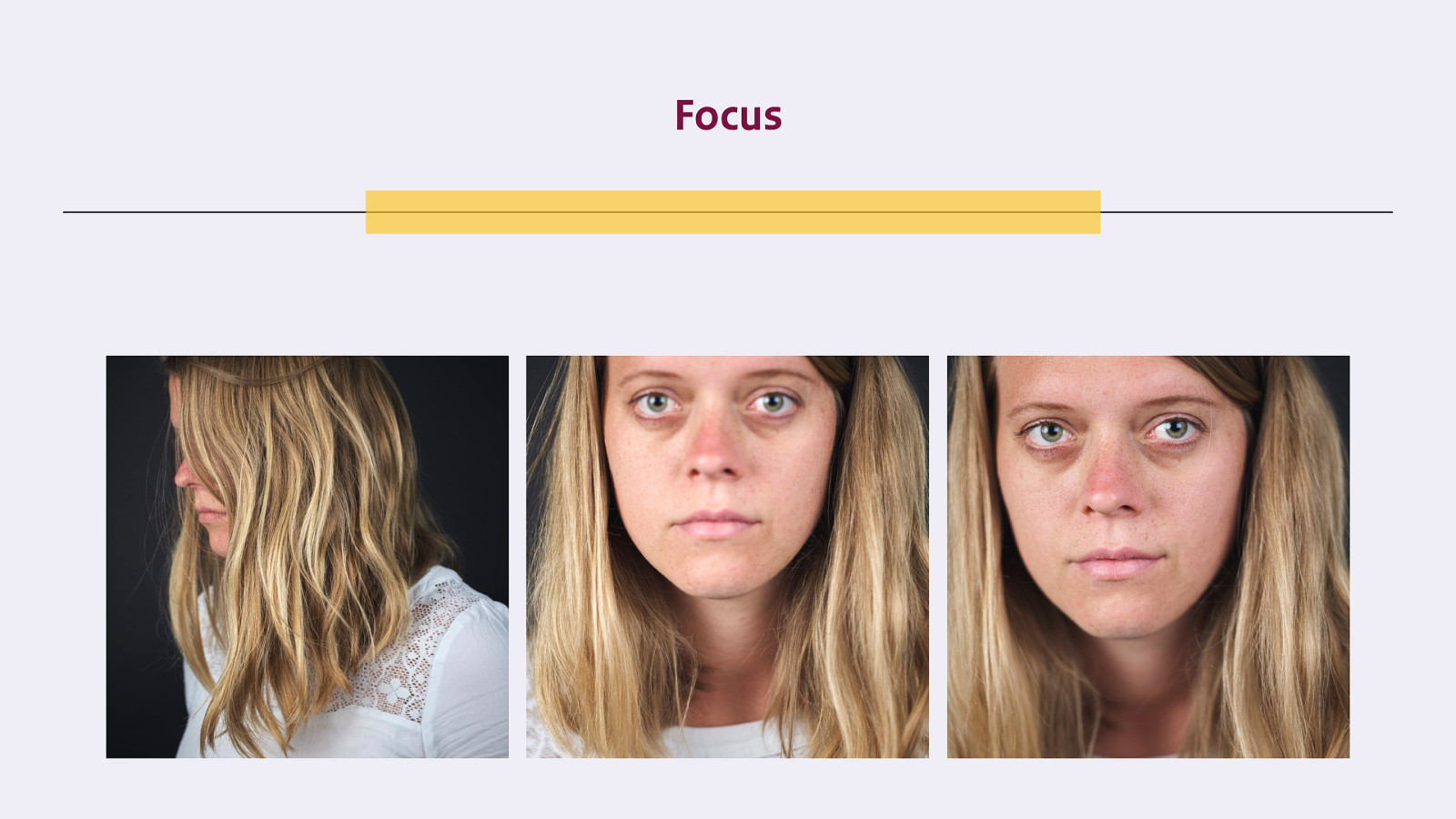

Another scale: focus. What do I want to focus on? What do I want to see, want to show the viewer. And as the portrayed one, what do you want to hide?

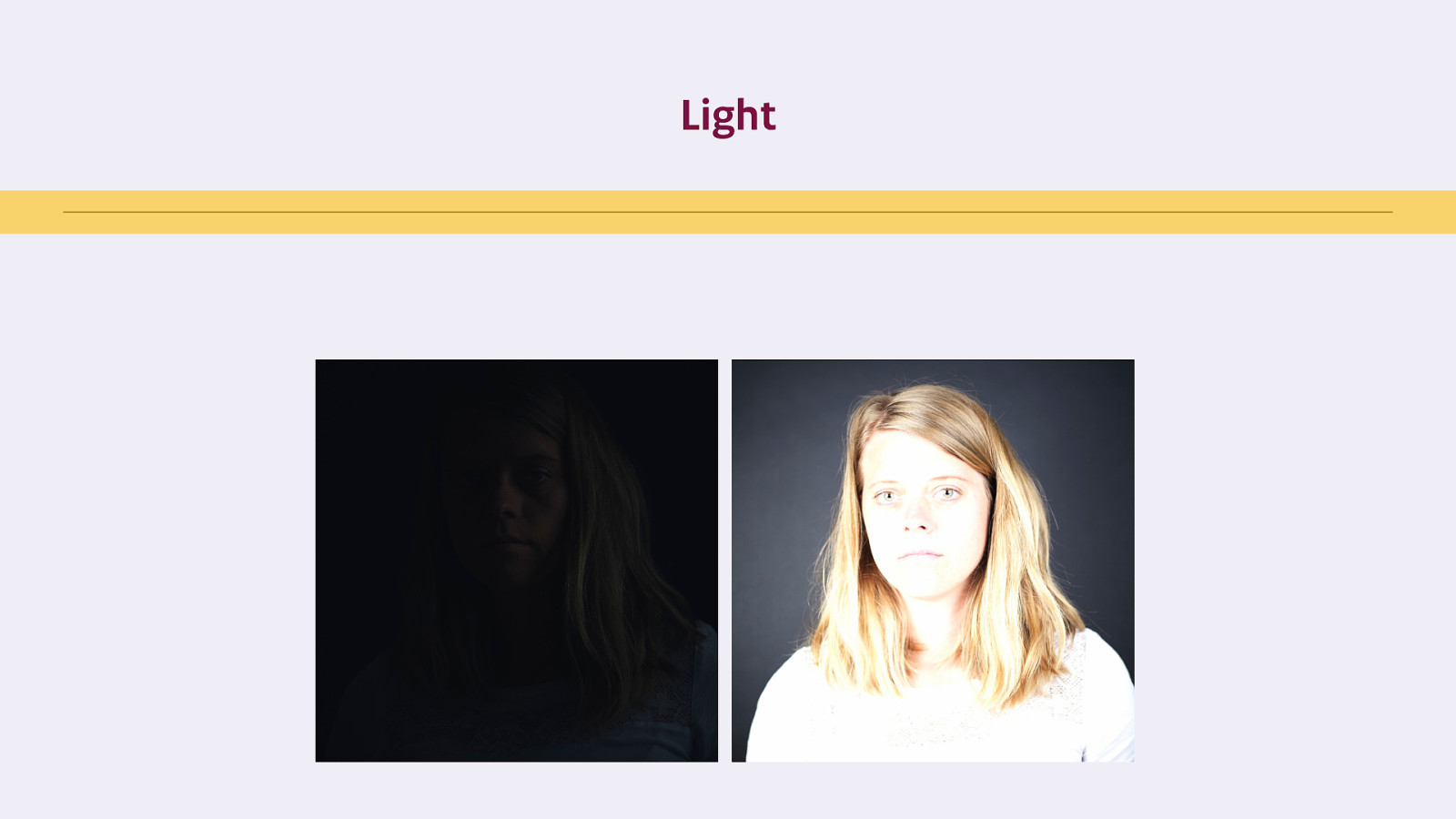

Light of course. In terms of light we often think the more light, the better. But you can play with light. And shadows can be exciting. They help you tell a story and can shift the attention to whatever part of the story you want to tell.

But light can also be too extreme. Either too dark so you can’t see anything anymore. Or too much light, so it is overexposed and you can’t see anything anymore either.

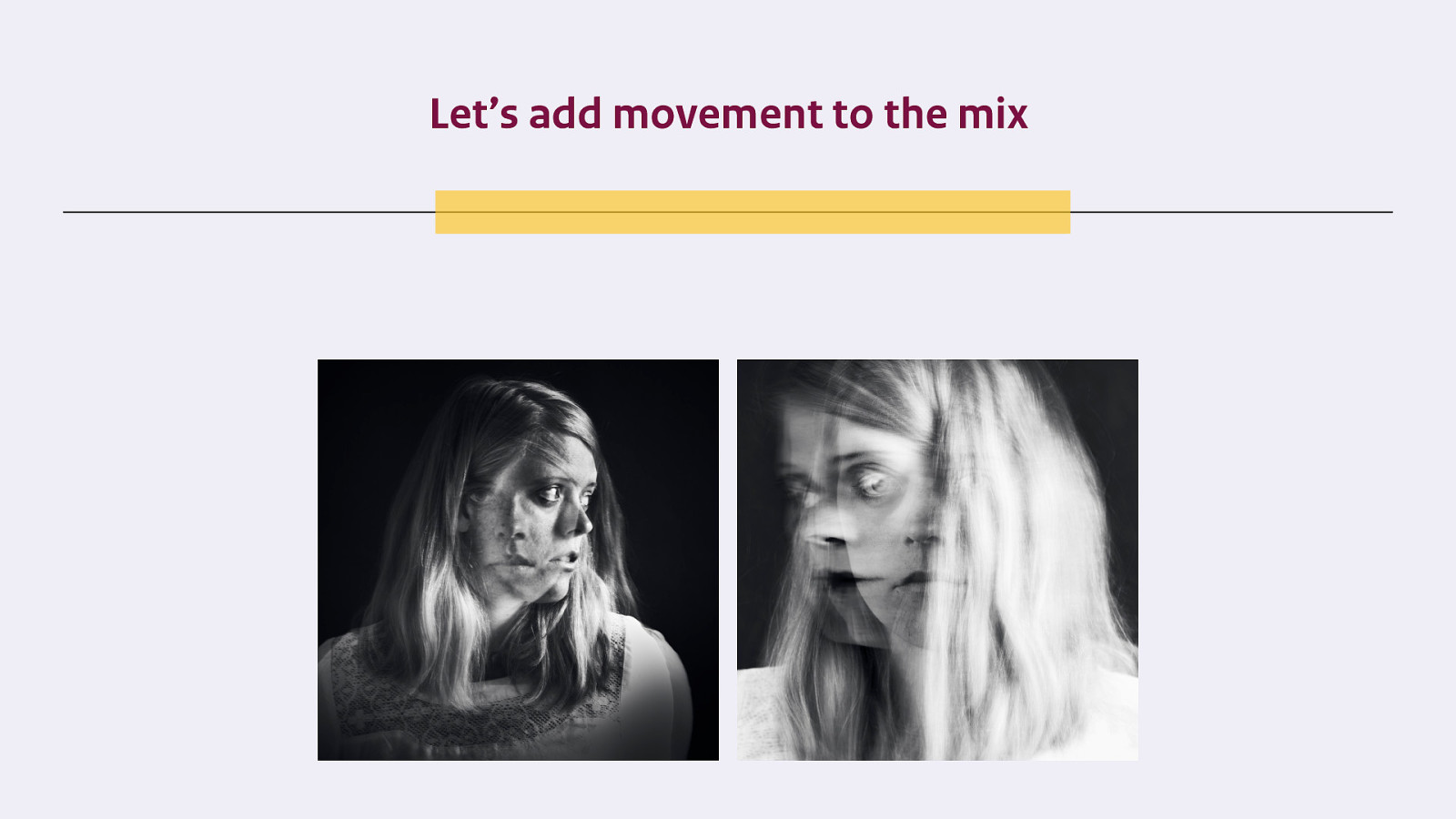

And of course you can combine all these scales and get really creative. This photo has a lot of light. To compensate I added a lot of focus and on top of that some movement.

With photography you’re not only telling a rational story, you’re feeling it too. And of course… empathy is a feeling too. So if empathy is a scale, as much as photography is… It was only a matter of time that I would start to photograph empathy. It’s time to bring back my colleagues…

I started photo-interviewing them about their empathy. I invited them at my house, I live very close to the office. We started with some coffee, and a conversation to ease into it. I used the pictures to explain the scale idea.

And I asked them to mind map or draw what they thought about their empathy. Just to help them on their way.

After about half an hour or so, we stepped into the studio. During the coffee I already got some images in my mind when my colleague was telling about her empathy. So together we tried to put these images on screen. And that looked something like this (video).

In this photo-interview we tried to use the language of photography to come up with a language for empathy. A very personal one, because it is yourself on the portrait. We started the photo-interview with one question: what would your portrait be as an empathic civil servant?

Together we reflected in the action to pick the best photo of my colleague’s empathy. And of course… I’d like to tell you some of their stories about their empathy.

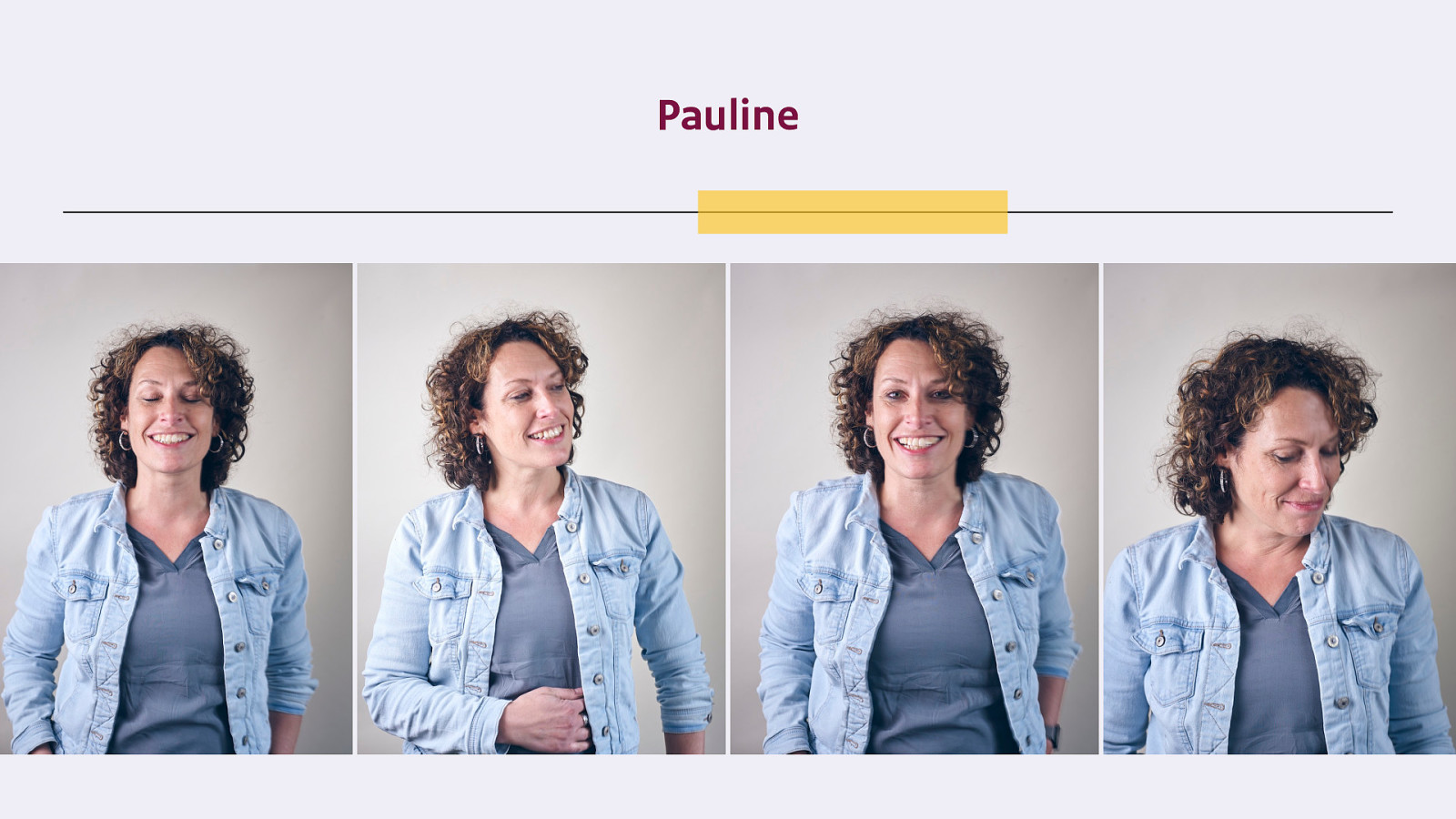

Let’s start with Pauline, she is my manager. Her empathy is about being approachable, she says.

In our conversation she told me that she wanted to be there for her team. That she would like her team to think of her as close, empathic but also approachable and no-fuss.

She also said that she thought that everyone would say that. Of course, no one is going to be photographed by me as a villain. So if everyone wants to be empathic… why isn’t our digital government empathic? According to her, it’s because we have a hard time working together. And that’s exactly why she wants above all else to be approachable.

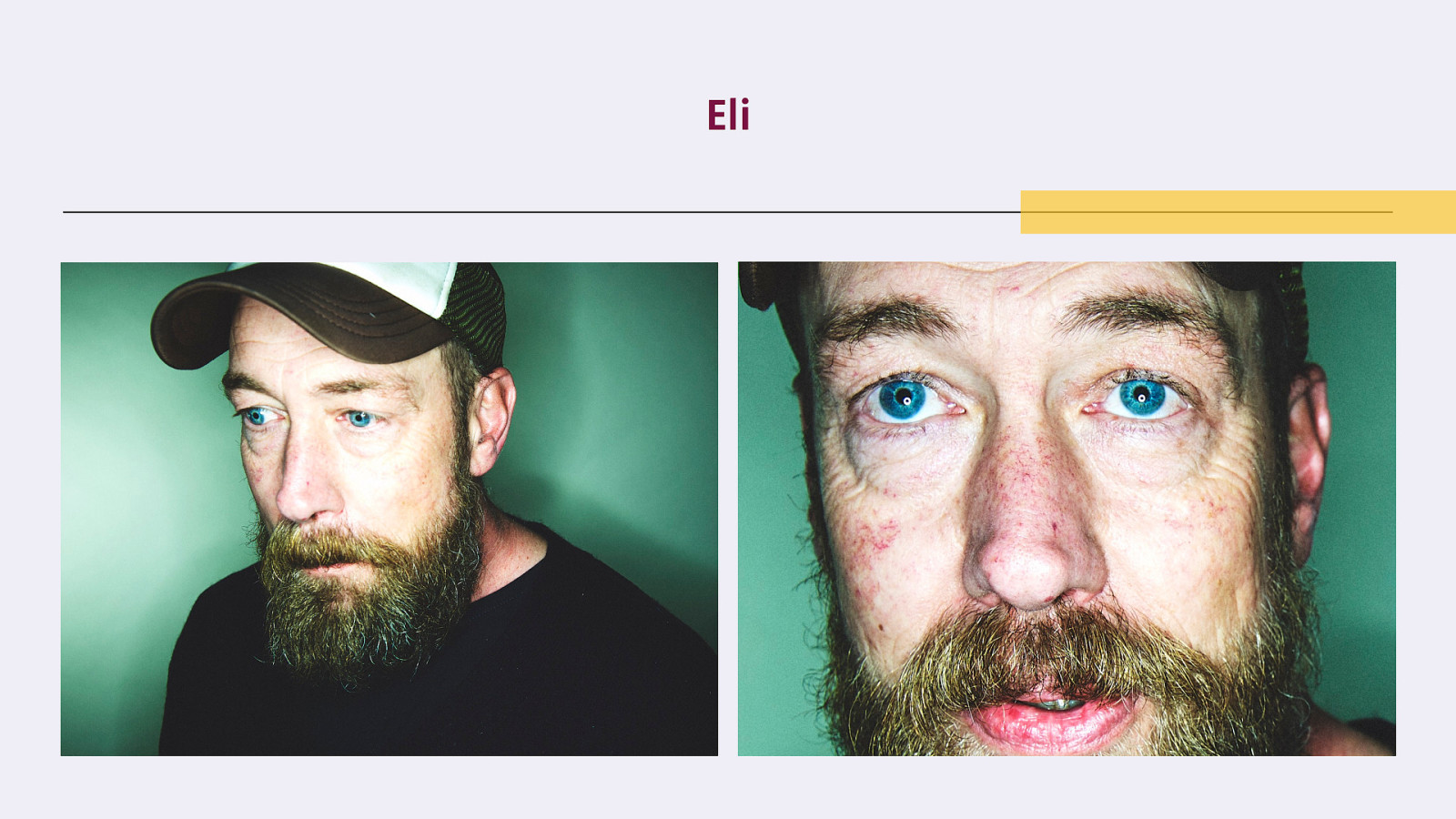

Next up is Eli. He is an interaction designer. During our session he told me this and I wanted to write it on the slide because it is so pure. He choose a lot of light and wanted to have as little distance as possible. You can even see a lot of distortion because I used the wide angle lens.

Empathy for him is honesty. He also told me that he had a hard time to be empathic. Because he felt so much distance to his users. “I don’t speak to them very often. And when I do, I am bound by all these laws. And most times I find it hard to design a webpage or a button, where I, not as a civil servant, bus as myself, don’t think it’s a good idea to push that button. For example when students take on big loans. I hate being to one designing stuff I don’t personally agree with.”

So for Eli… empathy is a struggle. Because he wants to have max empathy. He feels so much distance that he himself wants to be photographed really up close. On some of the photos you can really see his frustration.

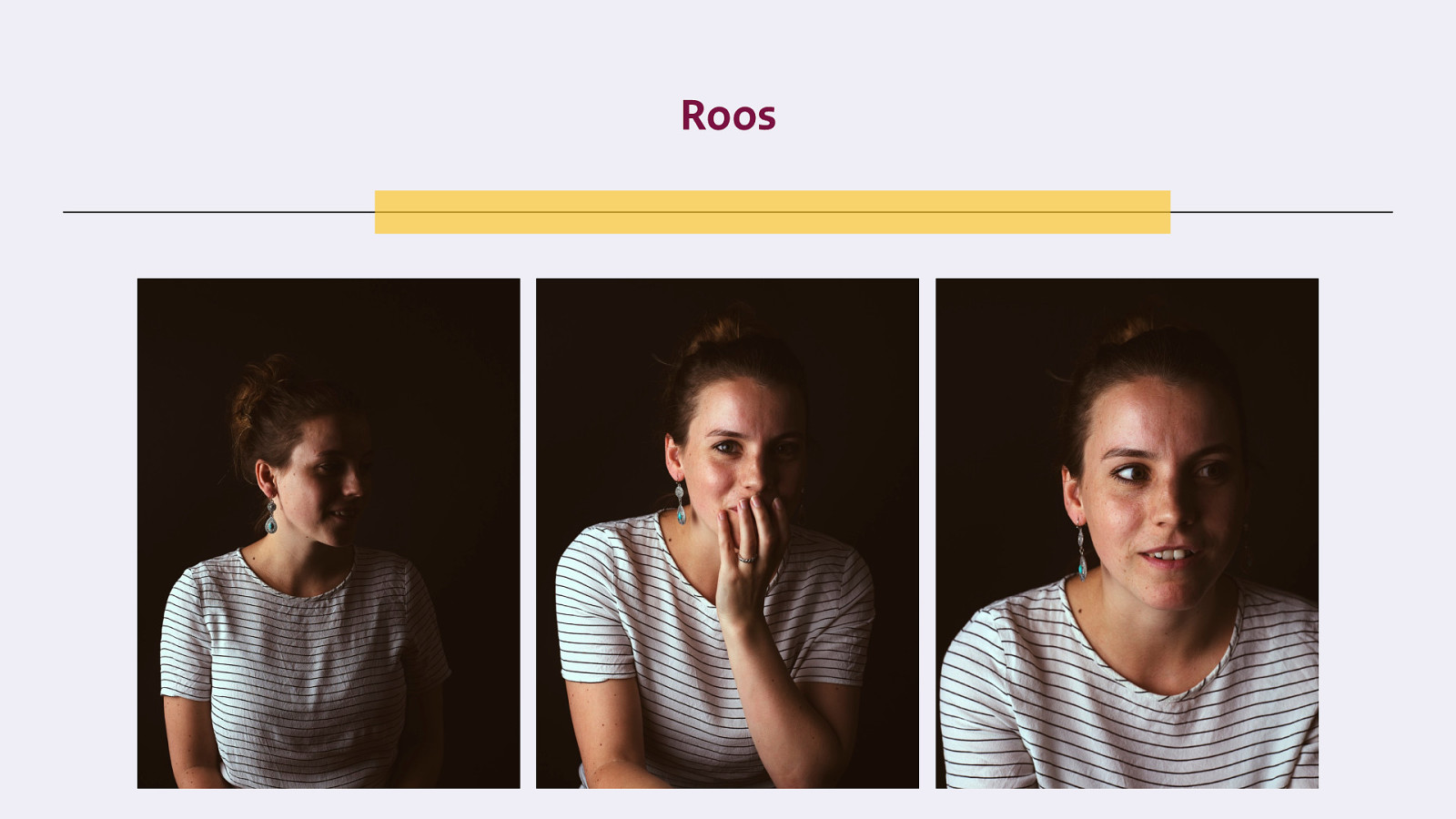

Roos. She says: “Empathy is always assuming the positive.”

Roos is doing the same job as I am, user research. Roos is a very positive person, always thinks of others. She started a couple years ago at our customer service and last year she made the step to become a user researcher. In het previous job she endured a lot of office politics with her contract. Even though, she still managed to look at everyone’s perspectives, even the ones from her bosses and from the organisation.

“Her job is to listen,” she says. “It’s not about me.” So she choose some shadows in her portrait. If users want she will keep a save distance, but if it’s okay for them she wants to come close and hear the stories and things they have to endure dealing with government.

So these are three of the stories about what I started to call empathic civil servants, or in dutch: begripvolle ambtenaren. I’ll be making more stories in the coming weeks and months.

But for now, while I’m here with all of you, I’m wondering…

what’s yours?

At this point you heard me express a lot of doubt and ask a lot of questions. You might even leave this talk with more questions than you had when you came in. I’m sorry about that. I really don’t have the answers yet. But I think that together we just might.

I’d like to ask you to help with my research, if that’s okay? Think about it for a minute: what is your empathy? What is your definition? How does it feel for you? How do you act empathic and where would you say that you are on this empathy scale?

What is your empathy?

I brought some cards with me. On the front it says: This is my empathy. On the back they are blank. Hopefully not for long. Because I’m going to ask you to write on the back what you think is your definition of your empathy.

In the front of the room I’m going to hang up the yellow robe again. And you can hang your card exactly where you want to be on the scale.

There are no rights or wrongs. Just take a stand and help me understand what empathy actually is. I will publish the cards on my blog, so please leave it anonymously.

Thank you so much for coming to my talk. I’d love to hear from you. Also, I’d like to know what questions I can answer for you now.