The Endless Sea

I wasn’t always a content strategist. For over 20 years I’ve messed about with computers, making things that go on the internet. Running UX teams in agencies and startups. Transforming the BBC with information architecture. Content strategy at Facebook.

When I reflect on that meandering career, I think about the connections. We often like to make distinctions between disciplines. Dirty, commercial, revenue-generating content marketing is one thing. Lovely, liberal, pious content strategy is something else. Basic tribalism at work, there.

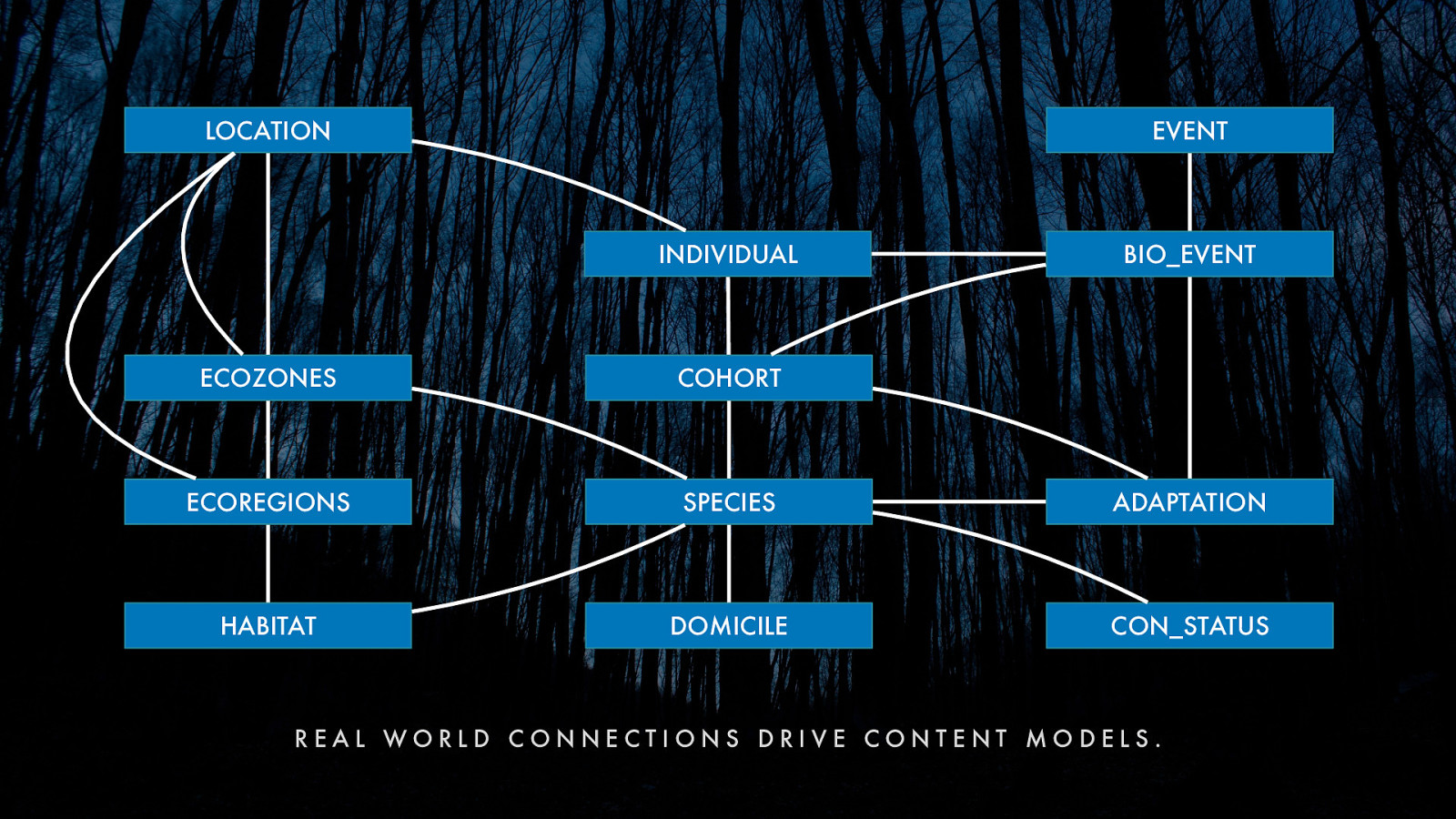

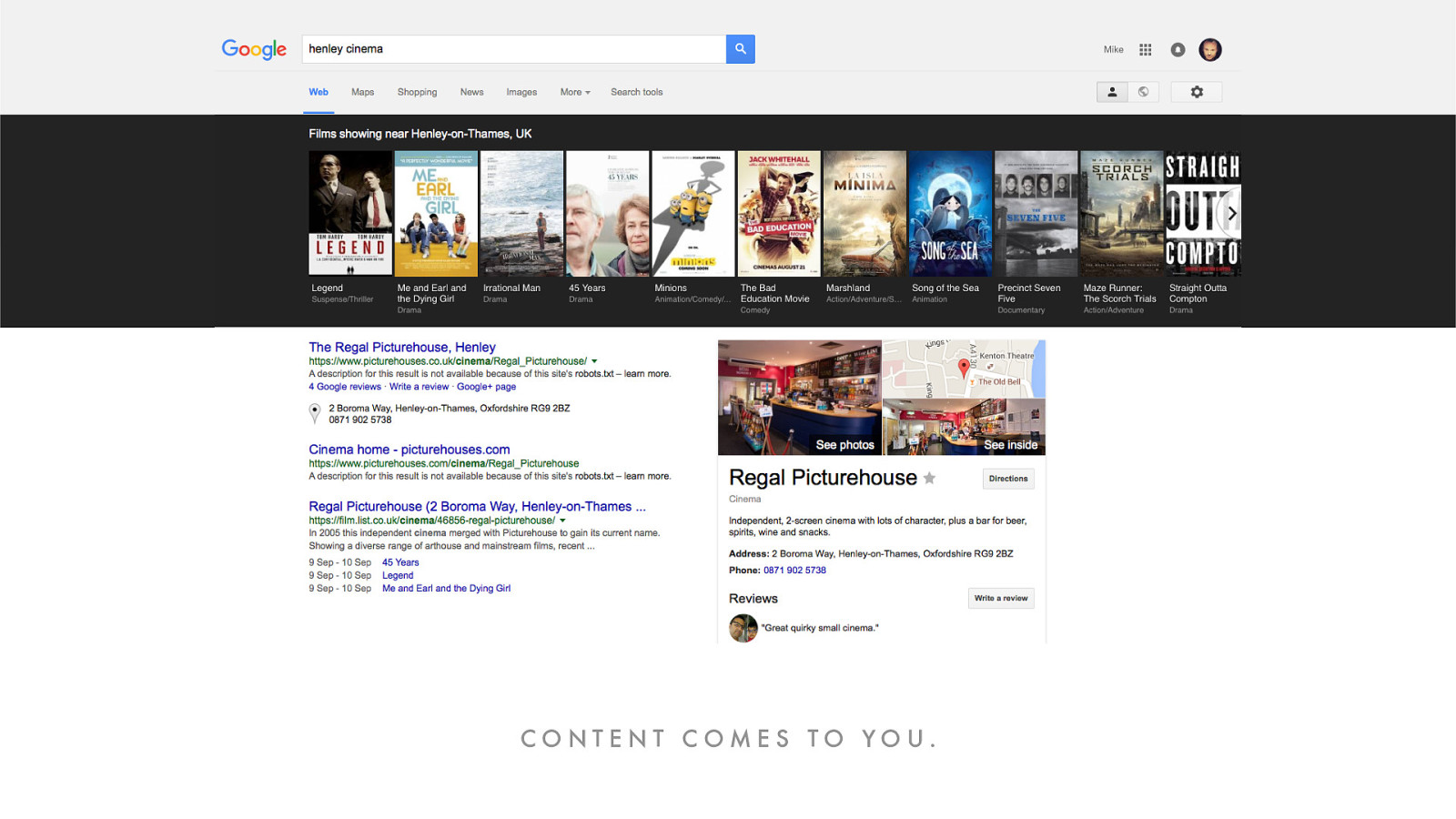

The disciplines that make digital things are far more interwoven than they are distinct. They coalesce in workflows that bring them even closer. Design. Engineering. Research. Content. Playing as one orchestra. Building a latticework of content and interaction, itself interwoven into the fabric of a global network. It’s connections all the way down.

It’s made me think about other times in history where acts of meaningful connection, be it between people or knowledge, have left behind lessons for the future. If you’ll indulge me, I’d like to share some of those stories with you now.